This story by the Center for Public Integrity was published in partnership with Grist and is part of a series on soil lead contamination.

Is lead lurking in the soil around you?

Dangerous lead contamination continues to plague the soil of urban centers, particularly in high-traffic, older neighborhoods where particles and airborne dust from leaded gasoline and lead paint accumulated during the 20th century. Industrial areas where both historic and current lead emissions have settled in the soil are also high-risk.

Decades of research have shown the lasting harm for children exposed to lead, which triggers a cascade of problems for brain development, impacting the capacity to learn, focus, and control impulses and other behaviors critical to navigating life. A growing body of evidence shows it also increases the risk of coronary heart disease, stroke, and chronic kidney disease.

But there are actions you can take to make your community safer.

1. Find out if you have a problem

Local experts might know where soil lead hotspots are located in your region. But if you can’t find information, try the online portal Map My Environment, a database showing lead pollution in soil, dust, and water across the U.S. and the world. The initiative originally launched at the Center for Urban Health at Indiana University–Purdue University Indianapolis, and now university scientists from around the globe participate.

You can explore lead levels on the interactive map and send in test samples to be analyzed for free. You’ll also see recommendations on lead interventions.

This map shows how common elevated blood lead levels are in children by census tract or ZIP code in 34 states. States fail to adequately test children’s blood for lead exposure, research shows, but existing data can point to potential trouble areas for soil, paint or water exposure.

2. Press for federal action

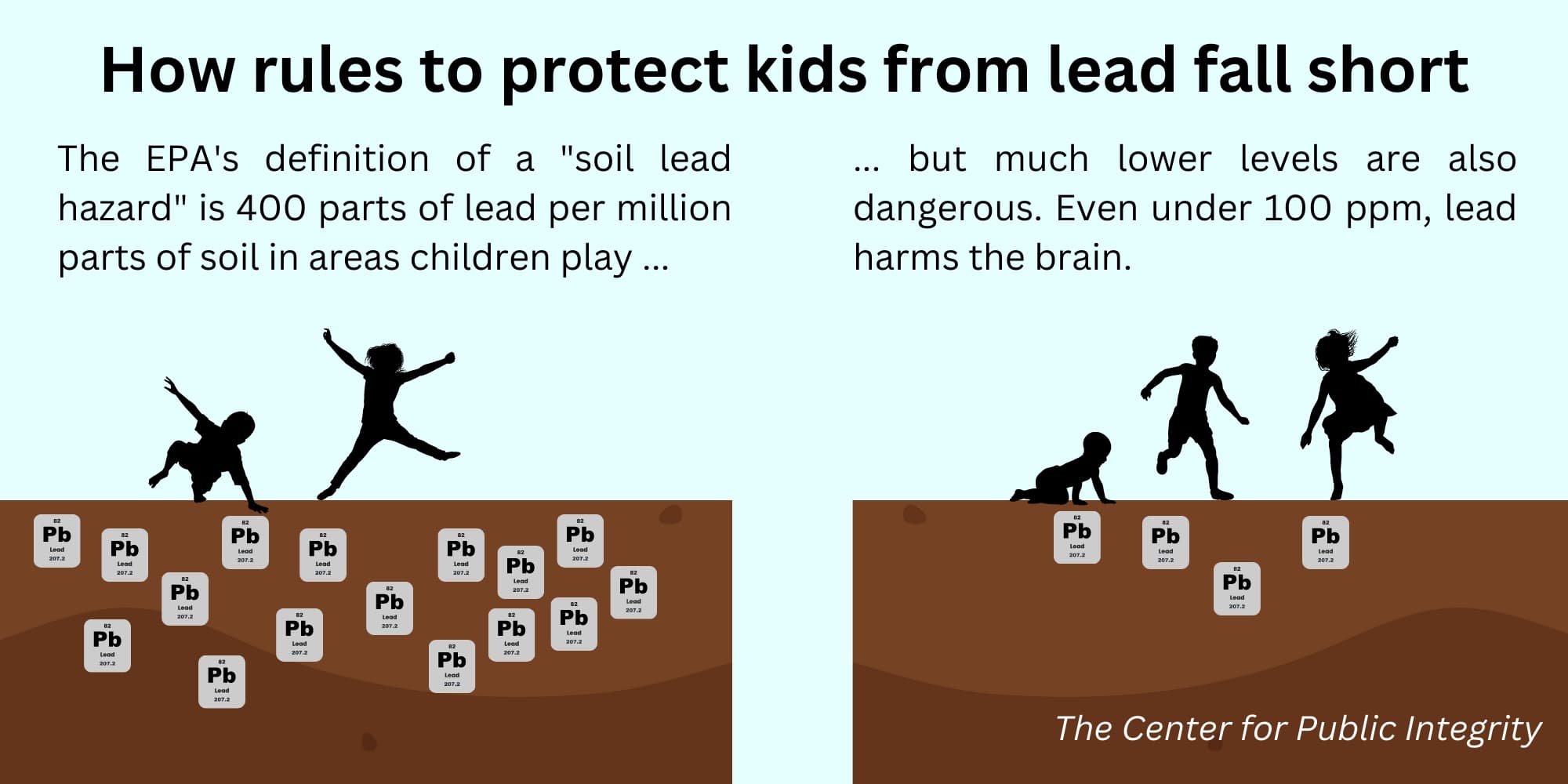

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency says it plans to address its outdated soil-lead hazard standards, which don’t protect people from harm because the thresholds are set too high. This reconsideration is part of a new strategy the agency announced in October to reduce lead exposures across the country, along with the higher risks borne by people of color and lower-income residents.

But the agency has not disclosed a timeline for revisiting the standards. And the current rules were set more than 20 years ago.

EPA Administrator Michael S. Regan has pledged that the agency will hold itself accountable by reporting its progress on the EPA website. In the meantime, you can get in touch with the agency and watch for opportunities to weigh in with a public comment. (Keep an eye out at Regulations.gov.)

In addition, the U.S. lacks a systematic approach to mapping urban soil contamination. That’s often left to academic researchers, but they say that funding for comprehensive testing to identify and monitor hotspots is difficult to get. Public pressure on agencies to support more urban soil testing could produce data that not only prevents childhood lead exposure before it occurs, but also leads to stronger environmental rules.

3. Team up

Research has shown that addressing pervasive, widespread soil lead contamination requires collaborative approaches that empower the people it’s hurting. This means recruiting leaders from neighborhoods with lead exposure risks, raising awareness about the health hazards, sharing ways that community members can protect their families, and finding solutions that work for their circumstances.

In Santa Ana, California, people did just that. Environmental justice advocates, concerned parents and scientists formed a coalition — ¡Plo-NO! Santa Ana! Lead-Free Santa Ana! — that conducted soil lead testing throughout the city and pressed local officials to act. Last year, the Santa Ana City Council updated the city general plan to commit to comprehensively addressing lead contamination hazards.

Halfway across the country, University of Illinois researchers partnered with Chicago residents to produce what they say is the first citywide map of soil lead contamination in that city. They found widespread pollution. With feedback from those same residents, the scientists designed follow-up studies and approaches to treat the soil to protect people.

4. Fight lead in soil with more soil

Soil lead expert Howard Mielke of Tulane University’s School of Medicine has found that if you change the surface of the soil in communities with high levels of lead, you protect people’s health.

In New Orleans, the city health department worked with Mielke to focus soil remediation in childcare centers, parks, and playgrounds by covering contaminated soil with clean soil. The city’s playground soils improved remarkably, Mielke said. Most cities can access lead-safe soil on the outskirts of urban centers, his research has found.

In New York City, meanwhile, soil expert Sara Perl Egendorf saw that residents weren’t sure how best to protect against soil lead contamination in urban gardens. So Egendorf helped create a network called Legacy Lead to tackle soil contamination throughout the city. One result: the NYC Clean Soil Bank. It offers residents free clean soil to cover potentially unsafe areas.

5. Keep an eye on research for new solutions

We know more now than we did a generation ago about how to contain lead. And new research keeps coming.

University of Illinois scientists, for instance, plan to do more research into slowing the spread of lead particles and protecting people from inhaling or ingesting the contaminated soil and dust.

Andrew Margenot, a soil expert at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, said there’s no silver bullet when it comes to remediating lead in soil. He envisions solutions that put nature to work. Adding trees as windbreaks could help trap wind-blown lead particles. Planting fruit trees can be a good idea because they transfer only minimal lead to their fruits. Covering the surrounding soil with mulch adds a protective layer.

6. Look for healthcare partners

The nonprofit Green & Healthy Homes Initiative in Baltimore is managing a program in Pennsylvania with Lancaster General Hospital, which is paying to provide lead-hazard-control intervention in 2,800 homes. They see the value in addressing a health threat — and hospitals in your area might, too.

“Every community can do this,” said Ruth Ann Norton, president and CEO of the Green & Healthy Homes Initiative. “It is just simply making the decision to do something that they know is so fundamental to their future.”

7. Engage younger generations

Kids are most affected by lead, but they probably don’t know much about it, especially the soil connection. You can work with local schools to get the word out.

Some scientists are taking their soil lead findings into the classroom in partnership with environmental justice activists, academics at three universities wrote in a 2021 study. Actions include teaching about the dangers of lead in soil; having students participate in soil-testing programs; and working to connect what they learn in school, such as chemistry, with examples of how scientific processes play out in their lives.

8. Run for office

You can get a lot done as an advocate for your community. But some actions, only elected officials can take.

Jessie Lopez first learned about Santa Ana’s lead-contamination problem through her work with the public advocacy organization Orange County Environmental Justice, which is part of the ¡Plo-NO! coalition. Then she ran for office.

Now, as a city councilmember and mayor pro tem, she can help chart Santa Ana’s path on lead. Among her actions: In 2021, she introduced a cutting-edge resolution adopted by the city council that declared a climate emergency while simultaneously pledging to limit or prevent exposure to lead and other environmental toxins in Santa Ana.

This story was produced in partnership with the McGraw Center for Business Journalism at the Craig Newmark Graduate School of Journalism at the City University of New York. This report was also made possible in part by the Fund for Environmental Journalism of the Society of Environmental Journalists, and by the Kozik Challenge Grants funded by the National Press Foundation and the National Press Club Journalism Institute.