Wheredja get those jeans?I spend a lot of time shining a light on murky areas of the food system, but what about the industrial-apparel complex? Just as the food we eat has a material basis and a history, so do our clothes. It turns out that I know a lot more about the (grass-fed, local) beef I ate last night than I do about the (non-organic) cotton T-shirt on my back.

Wheredja get those jeans?I spend a lot of time shining a light on murky areas of the food system, but what about the industrial-apparel complex? Just as the food we eat has a material basis and a history, so do our clothes. It turns out that I know a lot more about the (grass-fed, local) beef I ate last night than I do about the (non-organic) cotton T-shirt on my back.

Recently, a group of apparel-industry companies banded together to launch a tool to help consumers — and the industry itself — figure out the environmental impacts of our clothing choices. The Sustainable Apparel Association consists of big-name brands like Patagonia, Adidas, Nike, and Timberland, retailers Walmart, JCPenney’s, and Target, and well as Duke University, Environmental Defense Fund, and the EPA.

The plan is to develop a comprehensive database to track the ecological impact of clothing at every level of production, manufacture, distribution, and consumption, with the goal of giving every garment on retail racks a sustainability score.

The industry is smart to jump out ahead on the issue. According to The Believer‘s Andy Selsberg, journalist Elizabeth Cline is working on a book due out in the spring of 2012 that’s being billed as “the Omnivore’s Dilemma of clothes” — a reference to Michael Pollan’s 2005 blockbuster on the food system. “Fashion has parallels to food,” Selsberg points out. “Most clothing is too cheap, that cheapness has tragic costs, clothing is an agricultural product, and we consume too much of it.”

I recently caught up with two of the main forces behind the Sustainable Apparel Coalition: Patagonia executives Yvon Chouinard (founder/owner) and Rick Ridgeway (vice president of environmental initiatives). Here’s what we talked about:

Q. Say I buy a T-shirt from Walmart. What can this tool tell me about it?

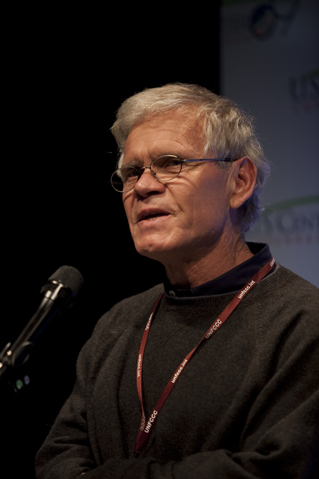

Rick Ridgeway.Photo: The Cleanest LineA. Rick Ridgeway: At the beginning of that life of a T-shirt, a designer would sit down with this tool, this index, and be able to make choices right on her or his computer about the materials that go into the T-shirt, and would be able to see what the environmental consequences of those choices would be right in front of them.

Rick Ridgeway.Photo: The Cleanest LineA. Rick Ridgeway: At the beginning of that life of a T-shirt, a designer would sit down with this tool, this index, and be able to make choices right on her or his computer about the materials that go into the T-shirt, and would be able to see what the environmental consequences of those choices would be right in front of them.

Let’s say the designer chooses traditionally grown [i.e., non-organic] cotton for the T-shirt. Life-cycle assessment data will be underpinning the whole index. So maybe the rating that comes out from that choice is inadequate, and the designer has higher goals. So, then she chooses organically grown cotton. Well, OK, the rating gets better, because, again, the index tool will capture the consequences of organically grown cotton versus traditionally grown cotton. But then, it’s going to tell her that the score’s still not as great as she wanted because she picked cotton that came from western China, and it’s drawing down an aquifer that’s not being replenished sustainably.

Then she has the option of selecting cotton from another part of the world where the cotton is grown with more dry-land farming techniques. But even then the score’s not so good, so then she goes, Christ, maybe I shouldn’t even have cotton, maybe there’s a blended fabric, or maybe I’ve got to go with more polyester that can be captured in a closed-loop process, recycled. The consequences of her decisions are going to be exposed and made visible by this tool.

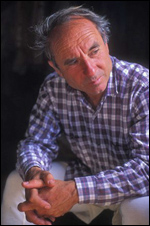

Yvon Chouinard.Photo: Rock RidgewayYvon Chouinard: I should explain that this goes a lot further than, say, organic standards for food. For instance, here in Ventura, Calif., there is one brand of strawberries that’s shipped from here to New Jersey, washed and packaged in New Jersey, and shipped back to California. That’s pretty crazy When you buy organic vegetables, the label doesn’t tell you if they’re grown in the Imperial Valley that’s draining the whole Colorado River, and there’s no rainfall there. Organic standards are very, very general, and it’s the same thing with certified fisheries. They certify the entire Alaskan fishery. Well, that is absolute bullshit, because just with salmon alone, if you’re catching salmon in the ocean, you have no idea where they’re coming from.

Yvon Chouinard.Photo: Rock RidgewayYvon Chouinard: I should explain that this goes a lot further than, say, organic standards for food. For instance, here in Ventura, Calif., there is one brand of strawberries that’s shipped from here to New Jersey, washed and packaged in New Jersey, and shipped back to California. That’s pretty crazy When you buy organic vegetables, the label doesn’t tell you if they’re grown in the Imperial Valley that’s draining the whole Colorado River, and there’s no rainfall there. Organic standards are very, very general, and it’s the same thing with certified fisheries. They certify the entire Alaskan fishery. Well, that is absolute bullshit, because just with salmon alone, if you’re catching salmon in the ocean, you have no idea where they’re coming from.

What we’re trying to do is really find out exactly where the stuff comes from. When you go to a restaurant these days, they tell you that the salad came from the so-and-so farm that’s just down the road. But we’re not doing that with clothing, we’re not doing that with fish, with a lot of things. This is one reason why we’re doing this as a coalition rather than waiting for the government to do it, because if they ever do it, the government’s going to have a wishy-washy standard with lots of loopholes, lobbying from the less responsible companies to lower the standards, and all of that.

Q. What phase of the garment industry is the most environmentally damaging?

A. YC: Agriculture. Coca-Cola did an environmental assessment of their Minute Maid orange juice. Everybody at Coca-Cola thought that transportation was going to be the biggest carbon footprint, because that stuff is shipped all over the world. But by far the biggest impact was agriculture, because of the energy use: the pesticide use, fertilizers, and on and on. It was like 80 percent of the carbon footprint. I think when you’re talking about clothing, what we’ve found out at Patagonia is the same thing.

When you’re shipping by boat, [the ecological footprint is] practically nothing. These ships are huge, they carry a lot, they create very little damage. When you’re air freighting, like a lot of clothing companies do, the footprint goes way up. But shipping is a small part of it. When we looked at all the fibers we’re using at Patagonia, the worst by far was traditionally grown cotton. That was a surprise because we thought the worst would be synthetics, because they use petroleum, and stuff like that.

But the way we use synthetics here, polyester specifically and nylon-6, which is one type of nylon that can be recycled almost infinitely, we’re finding out that it’s way better to use than cotton. Number one, the clothing lasts a lot longer, and we can start with a recycled fiber. We’re making all these jackets out of recycled soda-pop bottles. At the end of its life, it can be melted down to its original polymer and used again, which is pretty cool. What’s destroying the planet is consumerism — it’s not the total number of people we have, it’s the total amount of consumption. The whole world economy is based on consuming and discarding, consuming and discarding. To close that loop, start with the materials that you use.

Q. So the index will help us sort all of this out?

A. YC: Look, how do you buy your gasoline now? Do you try to buy from the most responsible gas company? [Laughs.] I mean, name one. We don’t know whether that gasoline is made from the tar sands, if it comes from Nigeria, which has one Exxon-Valdez spill every year, or it comes from the Amazon. As it is now, we have no idea. It’s just gasoline. We’re in the dark with consumer goods, and I can tell you that’s the reason I’m so excited about our index. If we want to change government, we have to change the corporations, because that’s who’s running the government. Well, don’t focus on changing the corporations, because you’re not going to do it. You’ve got to change the consumer. That’s us. We’re the ones. But as it is now, we don’t have the ammunition to make intelligent choices in our consuming.

Q. One of the most notorious things about the garment industry in general is labor conditions in manufacturing plants in the global South. Are there any labor standards working into this?

A. RR: Yes, there will be. We’re working on that right now. We hope to have the first version of those standards completed by June.

Q. Yvon, you said only consumers can push the apparel industry in more sustainable directions. Why not government?

A. YC: Consumers are the only hope. You think government’s going to solve our problem? Or corporations without any pressure are going to do the right thing? I don’t think so. It’s kind of like, who has the responsibility? Let’s say with tobacco. Here’s a product that’s guaranteed to kill you. So who’s responsible? Is it the grower that grows it? Is it the tobacco company that’s foisting this off on young people? Is it the retailer that sells tobacco? Is it the stockholder in the tobacco company? Is it the consumer who knows he’s going to die of lung cancer, and cause society a tremendous amount of problems taking care of him? I say they’re all responsible. Everybody.

Q. In the end it’s really about knowledge. For decades, the tobacco industry tried to suppress information about smoking. Meanwhile, they were lacing tobacco products with chemicals to make them even more addictive. It wasn’t until the knowledge broke out into the public that there was a huge effort to get people to quit smoking.

A. YC: I’m convinced that most of the damage done to the planet is done unintentionally. A lot of people don’t want to intentionally be evil like that, but they just don’t know. Given the choice, I think they’ll make the right decisions. You get five pairs of jeans in front of you, one is a 2 [on a 1-10 sustainability scale], and one is a 10, and you zap your little iPhone on the barcode to find that out, you’ll probably buy the 10. Without information, jeans are jeans, they’re all the same. I think it’s going to be a pretty powerful tool for consumers to use.

Read more about the Sustainable Apparel Coalition.