President Joe Biden signed the Inflation Reduction Act, or IRA, into law last week, unleashing hundreds of billions of dollars in tax incentives and rebates to help companies and everyday people transition to clean energy. While some of the new subsidies will expand renewable technologies like wind and solar, the law also offers generous incentives for carbon capture and storage, or CCS — projects designed to trap carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel-fired power plants or other industrial facilities, and then pump the CO2 deep underground, preventing it from ever entering the atmosphere.

CCS has long been controversial due to its high price tag, a history of failed projects, and the ways it enables continued fossil fuel use. There are only a handful of facilities currently capturing carbon in the U.S., and most captured CO2 gets buried in aging oil fields, where it benefits drillers by pushing more oil to the surface. Many climate advocates are skeptical that CCS can meaningfully cut emissions, or do so in a way that doesn’t harm neighboring communities. The Climate Justice Alliance, a coalition of 82 environmental justice groups, denounced the IRA in part because of its subsidies for carbon capture.

But while electric utilities have a lot of options for producing carbon-free power — like solar, wind, and nuclear — experts say that in other carbon-intensive industries, CCS is the most promising climate solution. “The steel industry and cement, they don’t have a very practical decarbonization option without using carbon capture equipment,” said Matt Bright, the carbon capture policy manager at the nonprofit Clean Air Task Force. That’s because steel and cement plants release CO2 from chemical reactions, not just from burning fossil fuels. “All of a sudden, the one technology that’s really viable for them is within reach,” said Bright.

The IRA makes key changes to 45Q, an existing tax credit for CCS, that make it much more lucrative and easier to access. Before, companies could earn up to $50 for every metric ton of CO2 sequestered — or $35 if they buried the CO2 in the process of oil extraction. Now, they can earn $85 or $60 per metric ton, respectively. (Note: The IRA tax credits also support a related technology called direct air capture, which removes carbon dioxide that has already been emitted from the atmosphere. However, this article is focused solely on carbon captured from polluting sources.)

Companies will also have more time to develop projects. Previously they had to start construction on the capture equipment by 2026 — a tight deadline considering it can take two to three years to get financing together and complete initial project planning, according to Bright. Now the deadline is 2033.

The IRA also opened the door for companies with smaller tax liabilities to take advantage of 45Q by allowing the tax credit to be collected as a direct cash payment, rather than a tax deduction, for the first five years a CCS project operates. After five years, the direct pay option will expire, but the credits can then be transferred to another company with a bigger tax liability in exchange for a check.

A fourth change is that the IRA dramatically lowers the total amount of CO2 that a project has to capture each year to qualify for the tax credits. Bright said this would enable smaller facilities that emit less carbon to pursue CCS.

However, there’s a chance this could lead to subsidies for large polluting plants that only capture a portion of their emissions. There’s one guardrail against that happening — for power plants, the CCS system must be designed to capture at least 75 percent of CO2 emissions from each unit of the plant it is installed on. It’s a low threshold, considering that proponents advertise that the tech can achieve upwards of 90 percent capture rates. Joe Smyth, a researcher at the nonprofit Energy and Policy Institute, also noted that past projects have failed to capture carbon at the rates they have been “designed” for. “If you’re designing for 75 percent, and it’s encountering some problems so it has to be turned off or fixed or whatever, you’re probably still going to be running the power plant,” he said. But Bright said that developers will have every incentive to capture as much as possible, since CCS is a multimillion dollar investment, and the tax credit is paid out per metric ton of carbon trapped.

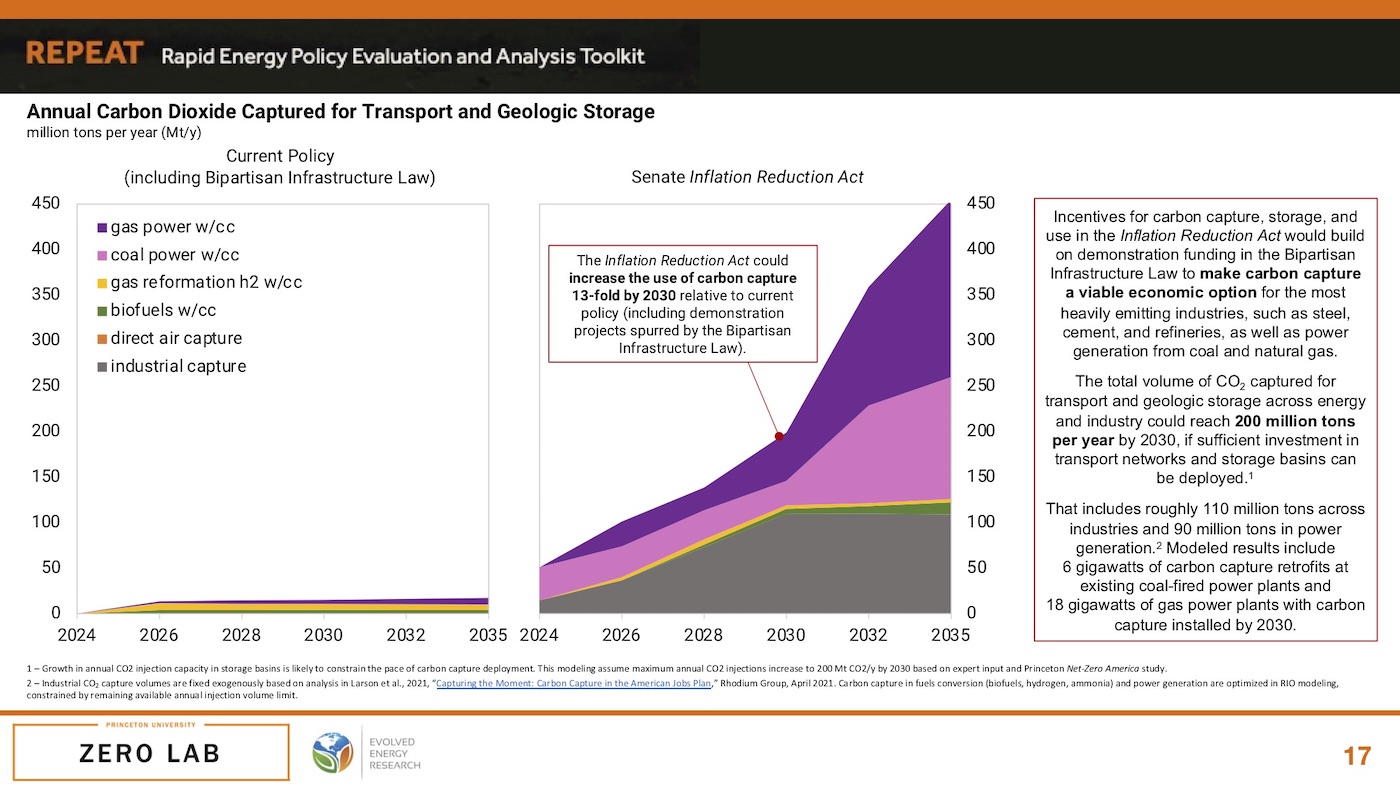

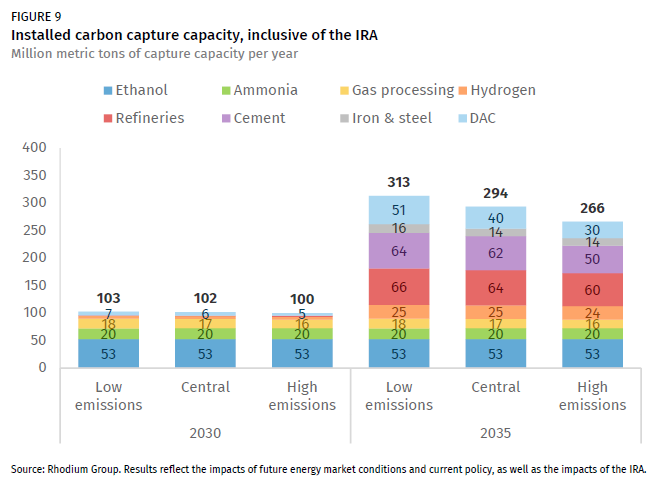

The IRA is expected to help the U.S. reduce overall emissions by about 40 percent below 2005 levels by 2030, compared with the 24 to 32 percent cuts we’re on track for today. But estimates of the role CCS will play in achieving that vary. A widely cited analysis of the IRA by the consulting firm Rhodium Group found that CCS could account for between 4 and 6 percent of that progress, and much more in the immediate years afterward. A separate analysis by researchers at Princeton University found potential for CCS to grow much faster, contributing as much as 20 percent of additional emissions cuts by 2030, and that nearly 1 billion metric tons of CO2 could be buried by that time.

However, a cost estimate of the IRA conducted by a congressional research agency came to a very different conclusion. It estimated that the new CCS tax credits will cost the government $3.2 billion over the next decade. At most, that would mean sequestering a total of 53 million tons of carbon if it was all used for oil extraction, or 38 million if the CO2 was solely buried underground.

It’s also not yet clear where CCS will take off. To date, much of the debate over CCS has centered around installing it on power plants. You might have heard of “clean coal,” a marketing campaign for carbon capture on coal-fired power plants. The Department of Energy spent hundreds of millions of dollars over the past decade to support CCS projects on coal-fired power plants in the U.S., but there is currently only one such plant operating in the world, and it’s in Canada. More recently, electric utilities have suggested they might explore CCS on natural gas power plants.

But while the Princeton group’s model predicts there will be roughly equal interest in sticking capture equipment on power plants as on other industrial facilities, the Rhodium Group analysis forecasts almost no CCS projects in the power sector. Ben King, one of the modelers at Rhodium Group, said that with provisions in the IRA for wind and solar, plus a new tax credit for keeping nuclear plants online, the 45Q subsidy just doesn’t make coal or natural gas plants with CCS cheap enough to compete.

Of course, there are a number of factors the models don’t or cannot take into account. Smyth, from the Energy and Policy Institute, a watchdog for the utility industry, said that in states like Wyoming and West Virginia where the fossil fuel sector is central to the economy, power plant owners will face pressure from elected officials to pursue carbon capture, even when it doesn’t make sense financially.

In a letter defending the IRA to the West Virginia Coal Association, Senator Joe Manchin, a key architect of the bill, wrote that he “fought for and delivered billions of dollars to help the coal industry transition by investing in the technologies necessary to continue using coal as a reliable source of power generation.” He argued that the direct pay option for CCS tax credits gave it an advantage over renewables.

Smyth said coal CCS projects come with a “whole host of concerns that are not addressed, and in some cases are exacerbated by carbon capture.” For example, even if the capture system works perfectly, it can lead to increased coal mining in order to power the carbon capture equipment. Burning that extra coal means producing more coal ash, a toxic waste product, and using more water to cool the plant. Depending on the other pollution controls installed on the facility, it can also mean creating more air pollution — which is likely to disproportionately harm Black and low-income people.

According to Smyth, the biggest determinant of whether “clean coal” lives or dies will be new pollution regulations that the Environmental Protection Agency will propose next year for coal power plants. The cost of compliance might be enough to end coal-fired electricity altogether.

In hard-to-decarbonize industries, the margins for CCS will still be tight. Bright said that estimates for capturing carbon at a cement plant, transporting it to where it can be pumped underground, and injecting it, fall in the $65 to $100 range per metric ton of CO2. For steel, they are in the $80 to $90 range. That means the tax credit may not fully cover the costs of CCS. These industries might face pressure from investors to decarbonize, but in most cases have no legal obligation to cut carbon.

And perhaps most importantly, the rosy forecasts for CCS do not account for a significant unknown moving forward: To make CCS work, developers not only need to install the capture equipment, but to build potentially thousands of miles of pipelines to transport the CO2 and injection wells to send it underground. “Can that happen? Like is that going to happen to the degree necessary to enable the level of deployment that we’re seeing in our modeling? I think that’s probably one of the biggest questions,” said King.

Right now, farmers and environmental groups in the Midwest are fighting to stop carbon capture companies from building CO2 pipelines. In Louisiana, where Black communities live in the shadow of refineries, chemical plants, and other polluting facilities, people would rather see those plants shut down than maintained with carbon capture equipment. Tamara Toles O’Laughlin, CEO of the Environmental Grantmakers Association and a prominent climate justice advocate, is worried that communities won’t have the power to decide whether or not they host these projects. She said that vulnerable people “are going to need a platform, information, and resources to make decisions about carbon capture amongst options, which should include a bigger share of keeping it in the ground.”

Opposing forces are at work here: In February, the White House Council on Environmental Quality issued guidance to government agencies to ensure that carbon capture “is done in a responsible manner that incorporates the input of communities.” However, Manchin only agreed to vote for the IRA because of a side deal to advance legislation that will ease the permitting process for energy projects, potentially limiting community engagement.

“It is concerning that the first climate bill in U.S. history invests so much of the peoples’ risk capital in carbon capture,” said O’Laughlin. “Tax credits will increase the number of speculators in the space, ramp up the number of experiments and create a wave of places where communities will have to advocate for themselves to separate the grifters and greenwashers from real community benefits.”