Back when he was in college, Paul Kearsley was — well, let’s just say he wasn’t running with the cool crowd. While his classmates were doing keg stands on the weekends, he railed against consumptive American culture. When an Industrial Design professor asked Kearsley’s class to create a surveillance system, his peers designed camera networks for prisons and fancy homes. Kearsley devised a system that could monitor a forest, and the data used to make recommendations on improving wildlife habitat.

Back when he was in college, Paul Kearsley was — well, let’s just say he wasn’t running with the cool crowd. While his classmates were doing keg stands on the weekends, he railed against consumptive American culture. When an Industrial Design professor asked Kearsley’s class to create a surveillance system, his peers designed camera networks for prisons and fancy homes. Kearsley devised a system that could monitor a forest, and the data used to make recommendations on improving wildlife habitat.

“I was on the outside,” says Kearsley, who lives in Bellingham, Wash. “I’d be asking, ‘Do we need a 2012 Honda Civic? What’s wrong with the 2011 Civic? Do we need more phones? What are the resources going into this? Where are they coming from? Who is this action hurting?’ A lot of the dialog stopped at ‘make it look cool,’ and I wanted to know more.”

Then, after graduation, someone lent Kearsley a 1,200-page tome that changed his life: Permaculture: A Designer’s Manual. As he read about a school of design devoted to creating productive, regenerative landscapes and resilient systems that “support life in all of its forms,” he knew he’d found his calling.

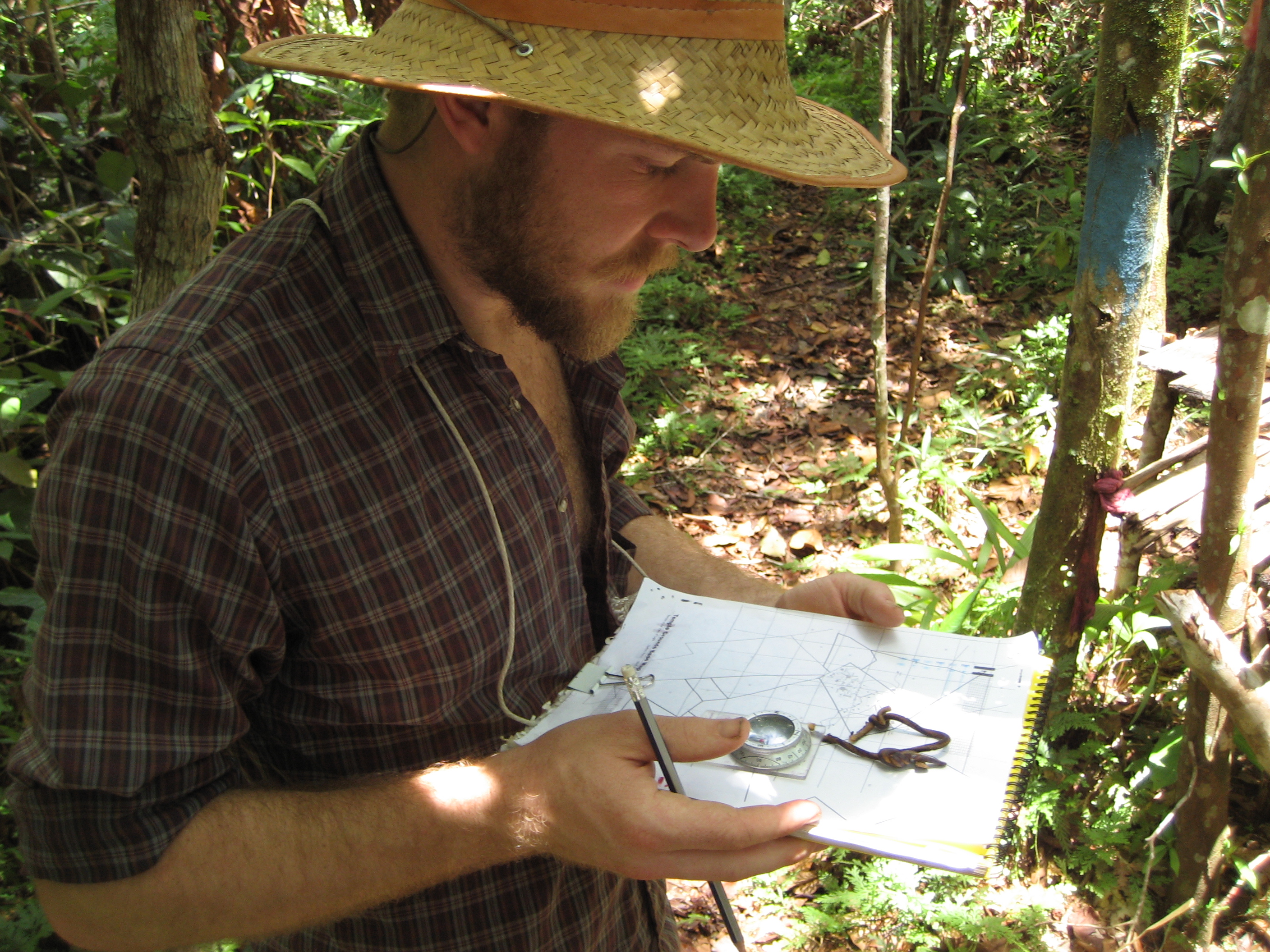

Seven years later, he owns not one, but two businesses — one focusing on permaculture design in his hometown, another consulting internationally. Along the way, he’s spearheaded the construction of Bellingham’s community garden, consulted on an eco-village in Costa Rica, and recently returned from Peru where he and a business partner shared permaculture principles with Amazon natives.

We caught up with Kearsley on a recent rainy day to talk about the relationship between ethics and food, intelligent design as he sees it (hint, it has nothing to do with God or Darwinism), and what goes well with venison.

Q. What, exactly, is permaculture?

A. Permaculture is a perspective, not a prescription. It’s how we address problems. My work consists of streamlining things and making more elegant sites and systems that not only meet the needs of the people but also improve the overall ecological health.

Q. Sounds vague … how do you pay the bills?

A. I design landscapes, but unlike a traditional landscape designer, I design systems to save energy and use minimal resources.

Q. For instance?

A. The conventional approach to turning an existing landscape into a garden is to haul out everything that’s there before starting. My business partner and I use a technique called “sheet mulch,” where we smother existing grass with cardboard, manure, straw, and mulch, and build the landscape on that. We’re using waste and cardboard to accomplish what would have been an intensive task of taking away sod or other plants, and we’re leaving the soil biology in its place.

Q. Spreading manure on a garden isn’t exactly rocket science, is it?

A. But creating the garden to operate as a system in conjunction with other systems — like using a rotating cast of animals to work the land in succession before planting — is. Permaculture is more than one specific technique. In every job, we minimize the use of fossil fuels required to build that landscape.

Recently, a client’s garden had a wet spot, and the traditional approach would have been to drain the whole thing and fill it above the water level. That would have required a lot of heavy equipment using a lot of resources to force the land into our notion of how it should be. Instead of that, we decided it made the most sense to expand the existing wet spot and making it a seasonal pond.

Q. That sounds like the path of least resistance. Is that permaculture?

A. Again, permaculture is as much a philosophy as it is a practice. The pond example isn’t radical in terms of land use, but it is out of the box in terms of business. We would have made more money with the traditional solution.

Q. Do you often make business decisions that cost you money?

A. I want to empower clients to maintain and even install their own gardens. I’m literally teaching myself out of thousands of dollars of work, but the bigger goal is to get more people in the community involved.

Q. Sounds great until you can’t pay your mortgage.

A. There are so many yards and so many gardens to take care of that I doubt we would ever have to find a new line of work. If we did, we would become shepherds or carpenters or something.

Q. Permaculture is a matter of “intelligent design,” right? Can you expand on that thought?

A. During school I was using the design process to create poster graphics, children’s toys, sandals, tape dispensers, and digital cameras. I found myself asking, “Why do we need another (insert new product here)?” “Why aren’t we solving (insert economic/ecological problem here)?” After graduating, my focus was to use my design process to develop practical solutions to real problems facing the planet, people, and the processes that direct our lives. It seemed like the intelligent application of the problem-solving/design skill set.

Q. Do you take issue with technology? My iPhone is elegant and useful.

A. I appreciate “appropriate technology” in the sense of the appropriate use of technology and also technology that can be appropriated — something you could fix or even improve. What’s important is not the technology itself but how it is being used. If you take a bulldozer or a tractor, it could be used to destroy a forest or to set up planting systems to grow orchards.

A lot of modern product design is constantly trying to push a new product across the shelf without questioning the value or need for that product. Most Americans replace their cell phone every year. When I consider the amount of resources that’s taking up, I can’t help but ask, “Who gave us that right?” My computer is seven years old and it still performs the functions I need it to.

Q. Permaculture started in the ’70s as a response to the “Green Revolution,” but it isn’t a particularly new concept, is it?

A. No. When you look at indigenous cultures from around the world, they’ve been doing the permaculture thing for as long as they’ve been people. The alternative is a culture that doesn’t last long.

Q. There are a lot of indigenous cultures that haven’t lasted.

A. Exactly my point. When your systems are out of balance, eventually it won’t last.

Q. Your consulting company, Terra Phoenix, just finished a job working with natives in the Amazon. What did you teach them about permaculture they didn’t already know?

A. One of the big issues with the local communities is that water systems full of pathogens are making people really sick. With a few pieces of technology and design principles — separating gray water from streams and keeping pollution and contaminants outside the watershed, introducing a slow sand filter — we taught them how to improve their system and stay healthier.

Q. Would you describe yourself as an environmentalist?

A. Probably, but I don’t fit into the usual definition. I like chainsaws, hunting, and eating meat. On Orcas Island [Ed. note: Kearsley learned the ropes at Bullocks Permaculture Homestead on Orcas Island, Wash.], the deer would come into the fruit groves and it wasn’t unheard of for one of them to end up on a dinner plate near a pile of plums.

Q. How can your philosophy of community and agriculture be extrapolated to an urban environment, where people are “farming” tiny garden plots and vacant lots in the middle of the concrete jungle?

A. In so many cities there are square miles of land that are being neglected or even oppressed, and there’s an opportunity to come together and transform that land from hubs of unsavory activity into a community asset. But on an individual level, people can grow food in their windowsills. Even if it’s just herbs, growing your own food is something everyone should experience.

Q. Give me one example of how an urban farmer could integrate permaculture.

A. Easy: house plants and worm bins. Almost half of what’s thrown away is compostable. I have a worm factory 360. Worms eat garbage and give rich fertilizer for plants, all in a contained system.