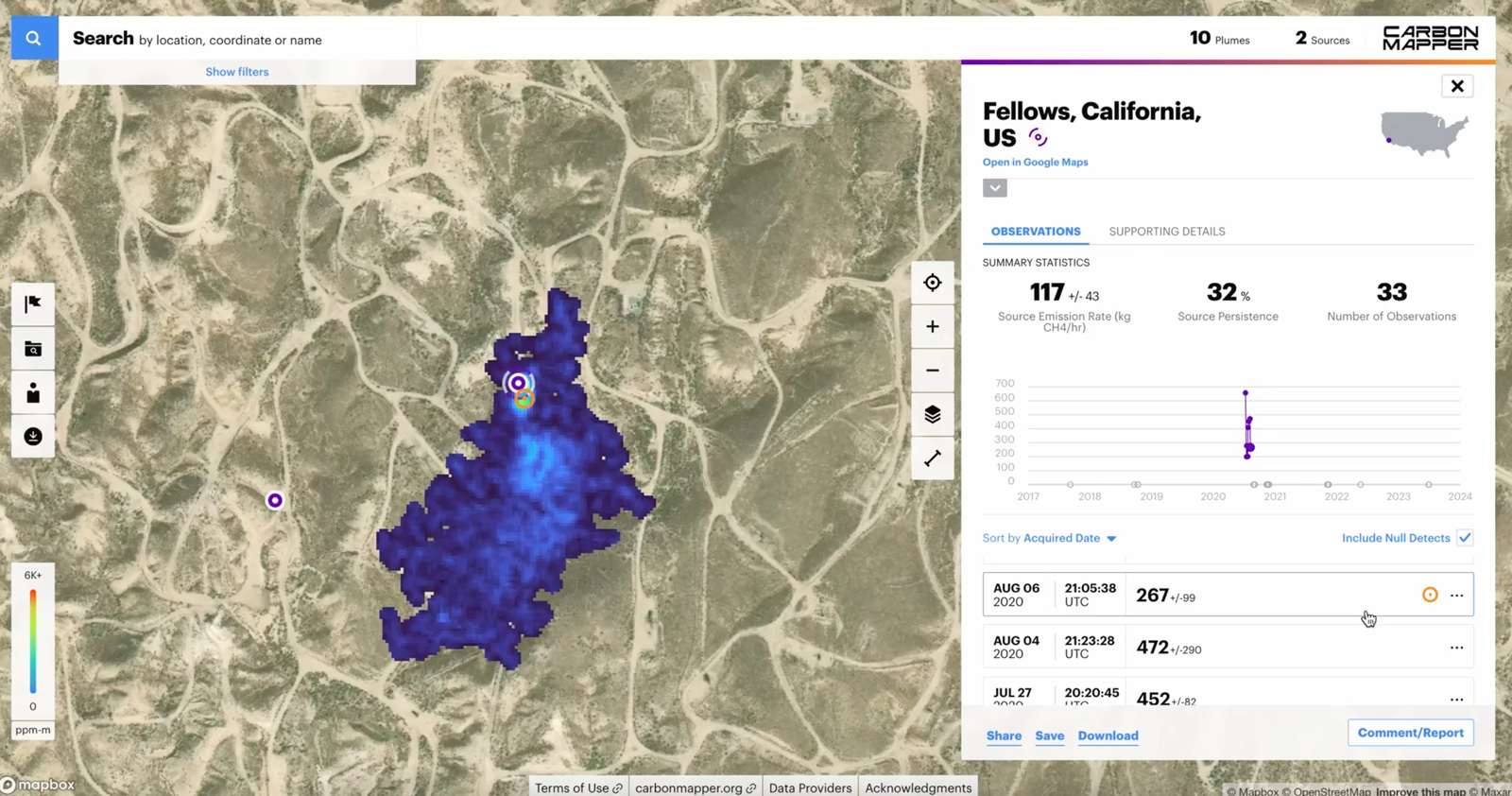

Scientists with NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory were flying a plane equipped with a visible-infrared imaging spectrometer over an oil field in California’s San Joaquin Valley when they made a worrisome discovery. Images produced by the device revealed a large plume of methane lingering in the air.

The plane made flights over the field for several more weeks, and while the plume shifted and changed shape with the blowing wind, its presence persisted. Believing the source could be a leak at the oil well, the scientists notified the operator. Soon, the plume disappeared. The leak, coming from a small fuel line, had been repaired.

“This is the essence of proactive measurement,” Riley Duren, one of the scientists involved in the flights and now CEO of Carbon Mapper, told Grist. “It’s a good example of how you would want it to work.”

The leak, detected in July 2020, was what’s called a “super emitter.” The term refers to events in which a lot of methane is quickly expelled, or to infrastructure that releases a disproportionately high amount of the gas. In oil and gas production, events can occur on purpose, as part of routine processes like venting (when producers intentionally release unburned gas) or by accident, due to faulty equipment or human error.

However they happen, super emitters release a particularly insidious greenhouse gas. Although it only stays in the atmosphere for about a decade, methane is 28 times more potent than carbon dioxide at trapping heat in the atmosphere. Because methane lacks color or odor, releases can go undetected for months.

Nearly one-third of methane emissions in the U.S. come from the oil and natural gas sector, and super emitters account for almost half of them. But a new emissions rule from the Environmental Protection Agency, or EPA, targets super emitters by leveraging technology like remote-sensing aircraft and even high-resolution satellites to not only find leaks, but to hold those who cause them accountable.

The EPA’s methane rule, announced December 2 at the COP28 climate summit in Dubai, includes a suite of regulations aimed at addressing the gas and other dangerous pollutants at oil and gas facilities. It establishes emissions standards for new equipment, phases out routine flaring of natural gas, guides states in regulating emissions from existing equipment, and requires the industry to conduct regular monitoring for leaks.

“Its importance should not be understated,” Darin Schroeder, of the Clean Air Task Force’s methane pollution prevention program, said of the rule. “Reducing methane emissions is the best action we can take right now to bend the climate curve.” The EPA predicts the new regulations will avoid 58 million tons of methane emissions by 2038, reducing projected emissions from the gas by 80 percent.

The rule also includes the “super-emitter program,” in which outside organizations certified by the EPA can use approved remote-sensing technologies, including airborne spectrometers and satellites, to monitor oil and gas facilities and detect large releases.

Under the program, watchdogs will report super-emitter events — defined as a release of more than 100 kilograms per hour — to the EPA, which vets the data and informs the operator. The owner must investigate and report back to the EPA within 15 days, explaining how and when it will fix the problem.

The EPA will also post verified super-emitter events on the program’s website, allowing those in frontline communities to monitor their possible exposure to dangerous gasses.

Schroeder said the program gives organizations that are already identifying leaks a way to make their data actionable. “They’re finding super emitters all over the place, but there’s nothing to do with that information,” he told Grist.

One of those organizations is Carbon Mapper, a nonprofit created in 2020 to drive emissions mitigation with data from specific facilities. The aircraft that Carbon Mapper uses carries an imaging spectrometer capable of measuring hundreds of wavelengths of light. Gases absorb different light wavelengths, leaving a “spectral fingerprint” invisible to the human eye.

Through a coalition that includes NASA, Planet Labs, and several other institutions, Carbon Mapper is also working to launch two spectrometer-equipped satellites to detect methane and CO2 directly at their sources.

Satellites are quickly boosting the potential of methane monitoring. The U.N.-led Methane Alert and Response System, launched at COP27, has used them to issue alerts on 127 plumes in the last year. The technology is also expected to play an important role in monitoring the new Oil and Gas Decarbonization Charter, announced at COP28, which commits 50 oil companies to drastically lowering their methane pollution by 2030.

In the super-emitter program, Duren of Carbon Mapper said outside monitoring will act as a backstop to the inspections oil and gas companies do themselves. The EPA rule requires operators to periodically check their infrastructure and repair leaks, but inspections are made bimonthly or even quarterly. “Super emitters are unpredictable,” said Duren. “There’s a lot of methane that can be emitted between that, which a satellite can catch.”

The new rule mandates that operators address verified leaks, something Andrew Klooster of the advocacy group Earthworks said they don’t always do.

As a field advocate in Colorado, Klooster uses a handheld camera called an optical gas imaging thermographer to track pollution. In a press briefing last week, he recalled visiting a site in Idaho last spring where, half a decade ago, the EPA had found problems with leaking storage tanks.

“Fast forward five years and these issues persisted, they had not been addressed,” said Klooster. “Without strong regulations and oversight, the oil and gas industry can’t be relied upon to strive for anything more than the bare minimum of emissions reductions.”

The program also could empower frontline communities. The EPA will publish confirmed super emitters on their website, making it easier for nearby residents to know what’s being released by neighboring oil and gas operations.

Releases can be dangerous in the short and long term: As the gas spills out, so do volatile organic compounds like benzene, which can increase the risk of chronic illnesses and cancers. During the 2015 Aliso Canyon methane gas leak, which lasted nearly four months, more than 8,000 households in the Los Angeles suburb of Porter Ranch had to be evacuated to escape a leaking well.

Joseph Hernandez, Indigenous energy organizer for Naeva, noted in the press briefing that Indigenous communities in New Mexico are surrounded by operating wells. In San Juan county alone, 27,000 Native Americans live within a half-mile of an oil and gas production site, he said.

As a former oil worker who lives on the Navajo Nation, Hernandez has seen the risks firsthand. “It’s not a question of if [leaks] will happen, but when,” he said. “Our communities deserve protection.”

How much the program protects people will depend on how effectively it is enforced, according to Lauren Pagel, policy director at Earthworks, who told Grist that currently, even states with strict methane regulations don’t have enough inspectors or high enough fines to compel companies to act. “Without on the ground enforcement, we could be in the same situation that we are in now.”

The EPA rule is expected to take effect early next year, but monitors must first be certified by the agency. It’s not clear yet how many organizations could apply to join the program. The Environmental Defense Fund will launch its own methane-detecting satellite in 2024. The company GHGSat operates 12 greenhouse gas-detecting satellites and says it will monitor every major industrial site in the world by 2026, but did not respond to requests for comment on whether it would participate in the program.

Access to the technology will be a barrier, and so will funding. Carbon Mapper relies on philanthropic support to conduct its monitoring. “It’s something that governments are going to have to step up to solve,” said Duren, “to make sure these programs are maintained and expanded and sustained.”

In an email, the EPA confirmed that the rule does not include funding, but said that the agency is partnering with the Energy Department to provide financial assistance for monitoring and reducing methane emissions from the oil and gas sector, which is “intended to complement EPA’s regulatory programs.”

As the oil and gas industry updates equipment to comply with other parts of the rule, Duren hopes that, eventually, there will be far fewer super emitters to detect. But that will take time. “We’re all going to be very busy with this for the rest of a decade.”

This post has been updated.