Can renewable energy turn Wales as clean and shiny as the Cardiff waterfront?Courtesy ttfnrob via FlickrThe sparkling, sanitized waterfront of Cardiff, Wales, reveals barely a hint of the country’s grimy industrial past. Where one of the busiest ports anywhere once shipped Welsh coal out into the world, a complex of upscale shops, pubs, and restaurants now dominates the area. Out are the sailors, brothels, and seedy watering holes. In are tourist-friendly pubs, fusion restaurants with names like ffresh, and a circus carousel. The locally favored Brains brewery (“People who know beer have Brains”) has survived nearby.

Can renewable energy turn Wales as clean and shiny as the Cardiff waterfront?Courtesy ttfnrob via FlickrThe sparkling, sanitized waterfront of Cardiff, Wales, reveals barely a hint of the country’s grimy industrial past. Where one of the busiest ports anywhere once shipped Welsh coal out into the world, a complex of upscale shops, pubs, and restaurants now dominates the area. Out are the sailors, brothels, and seedy watering holes. In are tourist-friendly pubs, fusion restaurants with names like ffresh, and a circus carousel. The locally favored Brains brewery (“People who know beer have Brains”) has survived nearby.

Even the bay itself has been remade. The natural tidal mudflats along the shore were too unseemly and smelly, developers figured, to attract new money. So authorities built a 0.7-mile dam to create a permanent artificial lake, tidal ecosystem be damned.

The only clear reminder of the country’s industrial heyday is the Pierhead Building, a red gothic-revival landmark that once headquartered a powerful shipping company. The first million-pound check was signed nearby and stored in the Pierhead a hundred years ago, according to national lore. After decades of going largely unused, the building was reopened this month as a museum, gallery, and civic forum.

The decline and tentative rebirth of the Pierhead is a telling stand-in for the story of Wales itself. A country of 2.9 million people, part of the United Kingdom, Wales was one of the first places to rise in the industrial revolution. Then it was one of the first to see its fossil fuel–based economy bottom out. Over the last decade, its government has invested heavily in clean-energy technologies, trying to cultivate a job base built on innovation rather than on mining and burning its natural resources.

I spent four days visiting Welsh companies and research hubs this month, on a trip funded by International Business Wales, a business-promotion arm of the government. The agency gave a biased perspective, of course, but one that revealed a lot about what Welsh leaders would like to achieve.

But I didn’t go because I was interested in Wales, no disrespect. I went to learn about the future of West Virginia, eastern Kentucky, Wyoming’s Powder River Basin, and other coal-dependent parts of the United States. Because those regions are following the same coal-driven trajectory as Wales. They just haven’t hit the rough patch yet.

You can look at Wales as the Appalachia of the U.K.—rural, hilly, beautiful, and, for much of the past two centuries, economically dependent on digging up and selling a fossil fuel. The key difference is that Wales built up its mining industry sooner, and saw it collapse sooner. But laws of economics promise the real Appalachia is following the same path.

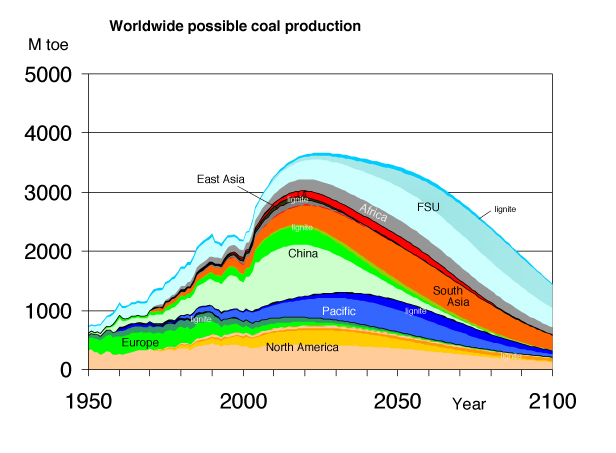

Here’s why: Coal is a finite resource. It’s running out. Not only that, it’s also getting harder and harder to reach. The Hubbert Peak model shows how this happens—here’s Grist’s David Roberts explaining:

The easiest reserves are found first. Over time, as more accessible seams are mined out, what remains is increasingly difficult to obtain and expensive to transport. In every coal field, every country, every region, the energy-return-on-investment (EROI) rises, peaks, and declines. Post-peak, it takes more and more energy to reach the coal and get it where it needs to go. The crucial issue is not how much coal is left in the ground but where we are on the curve, and more to the point, when we cross into negative EROI, the crucial line after which it takes more work to get coal out of the ground than coal returns in energy.

This graphic from the Energy Watch Group shows how Europe’s coal production (in lime green) peaked late last century, then shrunk to barely a sliver. North American production (in peach) is expected to level out over the next 30 years, then start its decline. Same trend, just a few decades later.

Peak and crash

To see how this plays out, it’s worth looking at the recent history of Wales. For much of the past two centuries, its coal-rich southern valleys formed the country’s economic backbone. English finance and technology helped build the mining industry, which in turn drove the shipping trade in Cardiff. Iron and steelmaking, which relied on abundant coal, were the next industries to rise.

But most Welsh coal is deep underground, often requiring miners to travel a thousand feet down to retrieve it. As Australia and nations in Asia and Eastern Europe began extracting coal that was closer to the surface and easier to collect, Welsh mines struggled to compete. The mountaintop-removal method dominant in Appalachia is even cheaper—blast open the mountain and there’s much less digging to do.

The decisive blow to the coal economy came from the miners’ strike that consumed Great Britain in the mid-1980s. Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government prevailed (despite the efforts of Billy Elliott), crushing organized labor all over Britain. Thatcher’s victory brought an unintended environmental boon by sharply reducing the mining of coal, the dirtiest of fossil fuels.

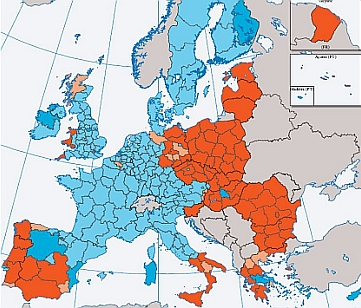

E.U. aid zones (in dark red), 2007-2013Courtesy wbc-inco.netWelsh mining continues in isolated pockets, including a two-year-old open-pit mine that is located an astounding 36 meters from private homes. But it has mostly vanished, leaving the country in rough economic shape. Its GDP per capita ranks last among regions in the U.K. Unemployment in some former mining valleys reached 25 percent. Many parts of the country are poor enough to qualify for European Union development aid, which goes mostly goes to former Soviet bloc countries.

E.U. aid zones (in dark red), 2007-2013Courtesy wbc-inco.netWelsh mining continues in isolated pockets, including a two-year-old open-pit mine that is located an astounding 36 meters from private homes. But it has mostly vanished, leaving the country in rough economic shape. Its GDP per capita ranks last among regions in the U.K. Unemployment in some former mining valleys reached 25 percent. Many parts of the country are poor enough to qualify for European Union development aid, which goes mostly goes to former Soviet bloc countries.

“We’re treated as the Third World of the U.K.,” one resident complained to me.

So it’s not hard to see why leaders want to emphasize new industries. And it’s not hard to see why they prefer knowledge jobs to extraction jobs.

But wanting to become a cleantech hotspot isn’t unique. Any number of places—New England, the San Francisco Bay Area, Denmark, Shanghai—have the same goal. What matters is follow-through. And the Welsh follow-through is impressively wide-reaching.

There is wind—25 farms generate 300 megawatts of energy, making use of open ridgelines and the coasts that border Wales on three sides. There is solar—several companies build panels, including Pure Wafer, which makes panels out of recycled silicon. Early-stage, experimental wave and tidal energy projects are planned for sites along the coast. A biomass plant produces electricity from waste wood (sawmill scraps, pallets, forest brush), and another set to open in 2011 would be the world’s largest.

The country has also drawn on the expertise in its universities, forming a multi-school Low Carbon Research Institute and a series of business incubators to find ways to shuttle innovations from academic labs into the marketplace.

Combined, it all adds up to … a promising start. The transition from dirty to clean energy hasn’t been easy, and 25 years after the collapse of the Welsh coal industry, its clean-energy sector looks more like a field of green shoots than a mature ecosystem.

“There’s no short-term fix for transitioning your economy from a carbon-intensive manufacturing base into something else,” said Helen Donovan, a cleantech specialist with the Welsh government.

Gordon James, director of Friends of the Earth Wales, offered a perspective from outside government. “We’ve got the ambition,” he said. “We’ve got the vision. They’re putting in place good policy, but they haven’t had much of an impact yet.”

Green shoots

Even in its early stages, the Welsh cleantech project offers lessons for what other mining regions can do to ease their transition away from coal. For one, Welsh leaders aren’t looking for quick fixes. They’re thinking long-term.

This is most clear in marine energy—tidal and wave power—an uncertain but promising sector that is generally considered a few decades behind wind and solar. Tidal and wave technologies are in development in a few other locations around the world—including Scotland, Washington state’s Puget Sound, and New York City’s East River—but they are preliminary enough that Wales, with 1,317 miles of coastline, could become a leader in both.

Tidal Energy Limited hopes to test this tidal system next February, Development Director Chris Williams says.Grist photo/Jonathan HiskesOne team of researchers hopes to dispatch a floating “wave dragon” that traps waves and redirects the water through turbines. The company Tidal Energy Limited plans to drop a triangular frame holding three 20-meter turbines onto the sea bed. A test deployment next year could reveal whether the project has real commercial potential. “We’re going to put it in the water for 12 months, prove it works, and then we’ve got something to shout about,” said Tidal Energy Development Director Chris Williams. “Then we can go to the banks. Then we can start looking at further leases and a wider business plan.”

Tidal Energy Limited hopes to test this tidal system next February, Development Director Chris Williams says.Grist photo/Jonathan HiskesOne team of researchers hopes to dispatch a floating “wave dragon” that traps waves and redirects the water through turbines. The company Tidal Energy Limited plans to drop a triangular frame holding three 20-meter turbines onto the sea bed. A test deployment next year could reveal whether the project has real commercial potential. “We’re going to put it in the water for 12 months, prove it works, and then we’ve got something to shout about,” said Tidal Energy Development Director Chris Williams. “Then we can go to the banks. Then we can start looking at further leases and a wider business plan.”

“We’re trying to pump-prime the industry,” said Helen Donovan, the government sustainable tech specialist. “If you look at the offshore-wind-energy and marine-energy situations, they’re very capital-intensive … By us sort of sharing the pain at the beginning, we’re actually pushing the industries forward over a period of time.”

Wales is also looking beyond its borders for help building a clean-energy economy—a tactic other coal regions could embrace. That’s helped it overcome the limited size of the local financial market. The Australian company Dyesol runs an R&D lab in north Wales focusing on advanced solar technology. The Japanese company Sharp has a solar-photovoltaic panel factory in the north; most of the panels are exported, but the company also runs a local installation training program.

Because Wales has multiple well-established universities, and because making the lab-to-marketplace leap is difficult almost everywhere, the country’s “bridge” projects could prove most consequential. Business incubators such Technium OpTIC provide lab and office space to promising startups, in energy and other high-tech fields, and help them find both government and private investment funding. Ninety percent of the companies it’s backed so far are still running, said OpTIC Sales Director John Oliver.

There’s a similar approach at the Low Carbon Research Institute, which is spread among six universities and funded by $50 million from the government and an E.U. development grant. It’s headquartered at the Cardiff University School of Architecture, where the work focuses on energy efficiency for new buildings and figuring out the economics of retrofitting existing homes in the U.K. Another branch at Swansea University contributes research to marine projects.

“The idea is to do serious, high-level academic work, but also, in a practical way, to move forward the low-carbon agenda,” institute director Peter Pearson said.

The “low-carbon agenda” is Wales’ goal to cut carbon dioxide emissions by 40 percent below 1990 levels by 2020. That’s more ambitious than the goals of the U.K., the E.U., and President Barack Obama. This aggressive target provides a clear impetus for the cleantech push—something else for coal-dependent regions to note.

Still, Wales has a long way to go to meet its goals. Data [PDF] from 2007 reveal a small decline in greenhouse-gas emissions that year, but James of Friends of the Earth argues that this owes more to Wales exporting its manufacturing to developing countries than to significant progress at home. Sixteen percent of Wales’ power supply still comes from coal, and 49 percent from natural gas. Renewable sources provide only 4 percent, according to 2007 data [PDF].

Two new power plants aren’t helping matters. The planned biomass plant and a liquefied-natural-gas plant that opened last year—the largest in Europe—will not capture and reuse waste heat, losing out on an opportunity for improved efficiency. “If we’re really serious about tackling climate change, we should not be granting permission to this,” said James. “It belongs to the past.” But the fault for this lies with the U.K. government, which approved the plants. Welsh political leaders wanted cleaner plants but were overruled.

Take a chance on me

The National Assembly building in CardiffCourtesy mark.hogan via FlickrBack on the waterfront in Cardiff, there’s one more landmark worth mentioning. Beyond the shopping complex and carousel, the National Assembly building looks like a sort of hybrid mushroom/manta ray. The building is only four years old and the legislature it houses only 12 years old. In 1998, the U.K. parliament granted “devolution” rights to Wales and Scotland, allowing their national assemblies the ability to choose how they spend most public funds (though not to set tax rates).

The National Assembly building in CardiffCourtesy mark.hogan via FlickrBack on the waterfront in Cardiff, there’s one more landmark worth mentioning. Beyond the shopping complex and carousel, the National Assembly building looks like a sort of hybrid mushroom/manta ray. The building is only four years old and the legislature it houses only 12 years old. In 1998, the U.K. parliament granted “devolution” rights to Wales and Scotland, allowing their national assemblies the ability to choose how they spend most public funds (though not to set tax rates).

The Welsh Assembly now leads one of three countries in the world that has a sustainability mandate in its constitution (France and Ecuador are the others). Last year it launched a comprehensive One Wales: One Planet development plan that calls for fossil-fuel energy use to drop 80 percent by 2025. The plan also requires all new buildings to be carbon-neutral by 2011. Because it was formed after the coal industry’s strength had faded, the Assembly has never had to grapple with the kind of powerful coal lobby that operates in Washington and coal-state capitals.

Throughout the trip, I kept asking “Why Wales?” For all the political leaders who talk a good game on driving the clean-energy transformation, why have theirs been able to follow through more than most? I got three general answers, two of which should be encouraging to the Appalachias of the world.

First, Wales never made a voluntary decision to give up fossil-fuel extraction. It was simply forced to find a new economic base. Every other coal-mining region will eventually reach this point too (though perhaps not in time to save us from a radically reshaped climate).

Second, Wales’ energy legacy made its citizens receptive to more energy investment, much as Texans accustomed to oil wells have embraced wind farms. It’s a point of pride. “Wales had an important history in the industrial revolution, so it wants to take an important role in the clean-energy revolution,” James said. “Even though we’re a small nation, there’s good ambition here.”

Finally, the political climate in Wales is, in a word, different.

Kontakt theater at the Pierhead Sessions.Grist photo/Jonathan HiskesI stayed an extra day in Cardiff and ended up at a quirky festival marking the reopening of the Pierhead Building. A youth theater troupe had persuaded members of the Welsh Assembly and civic leaders to join them in a program designed to get politicians and teenagers interacting at a personal level. At a series of small tables, one student actor and one grownup spoke about their daily lives, interests, and families. Every few minutes they switched partners, sometimes drawing pictures together, at one point getting up to dance awkwardly to ABBA’s “Take a Chance on Me.” It was strange theater that looked like speed dating. The whole event seemed remarkable—I couldn’t imagine American lawmakers accepting such an invitation and taking the chance that they’d look foolish.

Kontakt theater at the Pierhead Sessions.Grist photo/Jonathan HiskesI stayed an extra day in Cardiff and ended up at a quirky festival marking the reopening of the Pierhead Building. A youth theater troupe had persuaded members of the Welsh Assembly and civic leaders to join them in a program designed to get politicians and teenagers interacting at a personal level. At a series of small tables, one student actor and one grownup spoke about their daily lives, interests, and families. Every few minutes they switched partners, sometimes drawing pictures together, at one point getting up to dance awkwardly to ABBA’s “Take a Chance on Me.” It was strange theater that looked like speed dating. The whole event seemed remarkable—I couldn’t imagine American lawmakers accepting such an invitation and taking the chance that they’d look foolish.

After the day’s programs, which were open to the public and free, I watched Speaker of the Assembly Dafydd Elis-Thomas hold conversations with an intoxicated supporter, a filmmaker critical of the government’s environmental efforts, and a few others who wanted to talk politics.

I was struck by the level of access citizens had, at least that day, to the presiding officer of their legislature. I don’t know how you replicate an open political culture like that, but it’s been instrumental in this country-wide rebuilding project. Other fossil fuel–dependent places may need to create the same atmosphere to find their own pathways out of the past.