This story was originally published by HuffPost and is reproduced here as part of the Climate Desk collaboration.

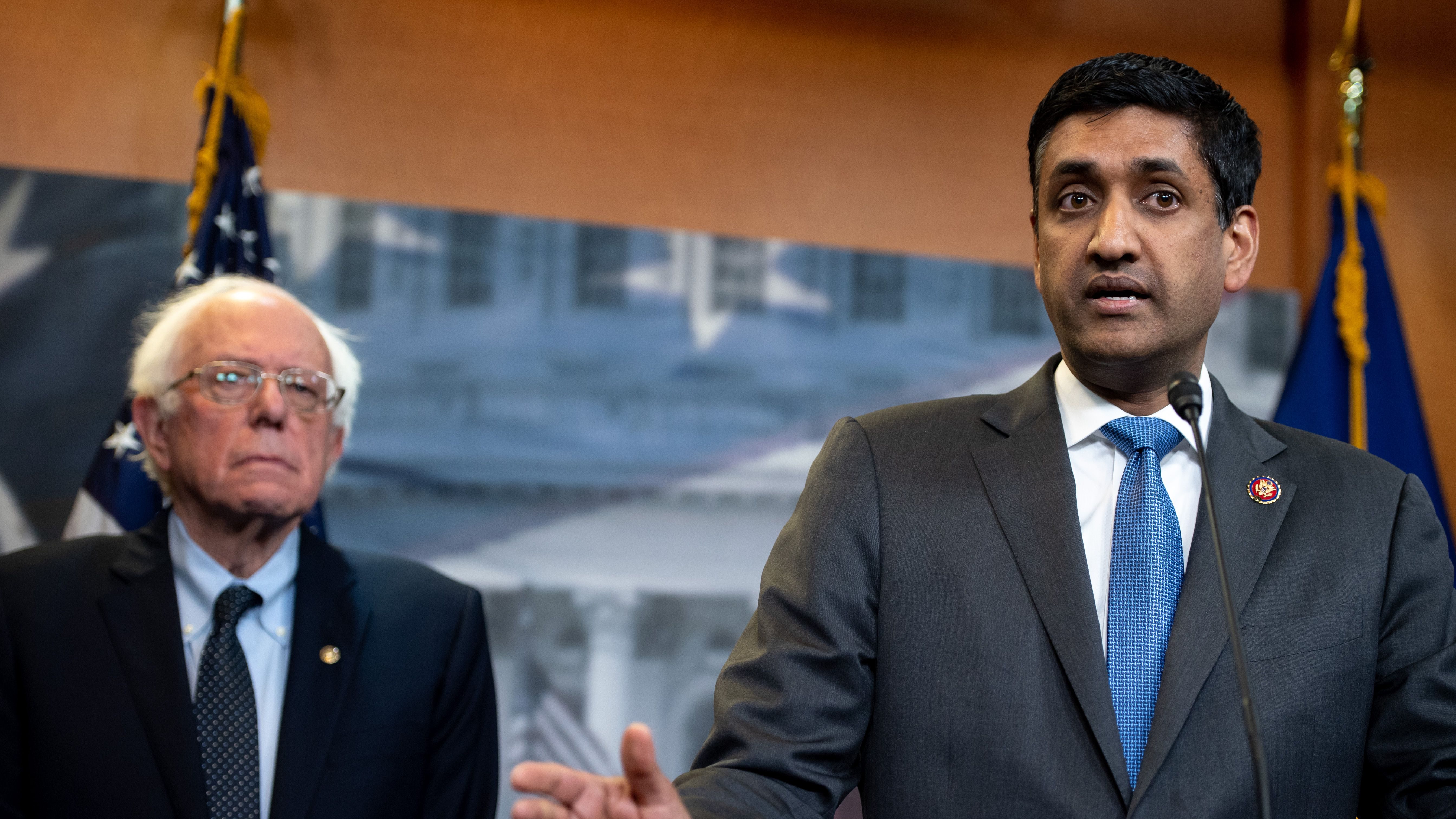

Representative Ro Khanna called for a public takeover of the investor-owned utility Pacific Gas & Electric Company as anger mounts over widespread blackouts aimed at keeping electrical equipment from igniting wildfires.

In an interview with HuffPost, the Silicon Valley progressive accused the power company of prioritizing high executive salaries and payouts to investors over infrastructure upgrades needed to operate safely in a hotter, drier climate.

“The for-profit motive does not work,” Khanna said by phone Wednesday. “The public utility is a much better option because you’re not having to worry about maximizing shareholder returns and you will make the safety investments that are necessary.”

Khanna is among the highest-profile elected officials to back a resurgent movement pushing for public ownership of power stations and transmission lines. Senator Bernie Sanders, whom Khanna has backed for the 2020 Democratic presidential nomination, proposed creating a public option for electricity as part of his Green New Deal and this week said it was “time to begin thinking about public ownership of major utilities.”

Maine Governor Janet Mills enacted a law in July directing state regulators to draft a plan to create a public utility to replace investor-owned power companies. Nascent campaigns to municipalize utilities in Chicago and New York City are gaining steam.

But the apocalyptic images of suburban homes and cars engulfed in flames and nightmarish stories of residents struggling to survive amid rolling blackouts in the country’s most populous state captured national attention this month and added new momentum to the populist campaigns.

PG&E, as it’s known, declared bankruptcy in January in the face of roughly $30 billion in claims stemming from its role in the last two years of wildfires. That includes the Camp Fire, the worst fire in California’s history, which last year killed 86 people and destroyed at least 14,000 homes. Officials found the company’s equipment responsible for sparking the blaze. As this year’s fire season approached, PG&E took the dramatic step of cutting off power to millions of homes in California in hopes of preventing sparks from power lines downed by strong winds from igniting dry brush.

The company warned that customers should expect rolling blackouts to continue for at least 10 years as it upgrades its infrastructure. Despite the shutoffs, PG&E said this week its power lines may have sparked two wildfires in the San Francisco Bay Area.

PG&E generated 21 percent of its electricity from solar and wind in 2016, compared to 17 percent from natural gas and none from coal, according to the company’s figures, making it a notch greener than California’s power mix overall.

But Khanna said a publicly controlled utility freed of the requirement to pay investors dividends could transition much faster to zero-emission sources. He cited Silicon Valley Power, the municipal utility in Santa Clara, which this year generated nearly half its residential electricity from solar and wind.

The utility, Khanna said, “is a shining example” of what California lawmakers could transform PG&E into: a locally controlled nonprofit rapidly reducing its emissions and preventing power outages.

“When you have the public that’s running the utilities, they’re going to care about the consequences of climate changes,” Khanna said. “They’re going to support renewable energy. They’re not going to be motivated by profit.”

PG&E’s profiteering has particularly rankled Californians watching their homes burn, businesses suffer, and medical clinics close as modern necessities like phones, refrigerators, and electric cars become useless. Just before blackouts began earlier this month, PG&E wined and dined about a dozen employees of the company’s gas division at a ritzy Napa Valley winery. PG&E CEO Bill Johnson apologized for what he called an “insensitive” and “tone deaf” event after the San Francisco Chronicle reported on the gathering.

“While the event was planned for about a year, we sincerely apologize for the insensitivity of the timing and location of the event,” Jeff Smith, a spokesman for PG&E, said in an email Thursday. “Moving forward, we will no longer hold these types of events.”

But Johnson’s own pay has drawn criticism. The executive, who earns a base salary of $2.5 million a year, could net $110 million if share prices return to a 2017 peak as part of a bankruptcy deal, according to the Sacramento Bee.

“That’s incomprehensible to me,” Khanna said. “We ought to have conditioned executive pay at PG&E on fixing the safety risks and repairs.”

But Johnson, 65, joined the distressed company at a high price in April after leaving his job as the head of the federally owned Tennessee Valley Authority, where he made $8.1 million in total compensation per year. That, according to the Tennessee-based Knoxville News Sentinel, made him the nation’s highest-paid federal employee.

The TVA, in some ways, serves as a model for what Sanders proposed under his administration, a government-run power company that provides low-cost electricity to ratepayers whose bills, rather than enriching investors, would go toward rapidly increasing the country’s stock of zero-emission generators. The power sector is the second-largest U.S. source of climate-changing emissions.

But an ideal public power network would be less centralized, with distributed renewable generation, batteries, and transmission lines that would make the system less vulnerable to fires and extreme weather events, said Johanna Bozuwa, a public power expert at the Washington-based think tank Democracy Collaborative.

“We are not trying to create the institutions of the past,” she said by phone. “We’re thinking about a totally new system.”

That includes reforming public utility commissions. The regulatory bodies now prioritize profit for investor-owned power companies and fall victim to “regulatory capture” when private utilities deploy their war chests to finance election campaigns and lobby sitting officials. Publicly owned utilities wouldn’t have the same spending power. And states could create oversight boards, such as the entity Paris established when the French capital brought its private water utility under public control nearly a decade ago.

“We’re not going for public ownership; we’re going for democratic public ownership,” Bozuwa said. “We’re seeing more people think really critically about how we build the public ownership models that are going to work for us and not just create this arms-length corporatized version of public ownership.”

Public takeovers could, in theory, slow some utilities’ transition away from fossil fuels. Boulder, Colorado, started the process of municipalizing portions of the investor-owned Xcel Energy’s grid nearly eight years ago, and it remains locked in a legal fight over the process. But Bozuwa credited the effort with accelerating the Minneapolis-based Xcel’s bid to transition to 100 percent carbon-free electricity by 2050.

Similar calls are growing in California. In September, San Francisco offered PG&E $2.5 billion to buy portions of the grid that serve the city, but the company rebuffed the proposal. Earlier this month, neighboring San Jose followed suit, with Mayor Sam Liccardo announcing the city is considering a range of possible options to form its own utility.

PG&E did not respond directly to questions about the campaign to bring it under public ownership. The Edison Electric Institute, an investor-owned utility trade group of which PG&E is a member, did not return a request for comment on Thursday.

California Governor Gavin Newsom isn’t sold on the idea. The first-term governor invited billionaire Warren Buffett to buy PG&E earlier this week. Berkshire Hathaway Energy, Buffett’s utility conglomerate that operates power companies in six Western states, did not respond to a request for comment.

But Khanna criticized the governor’s proposal. California could issue bonds or spend some of its budget surplus, he said, to buy the utility, break it up, and put the grid in the hands of local nonprofits modeled on Silicon Valley Power.

“The idea of having a private entity like Berkshire Hathaway buy it makes no sense,” Khanna said. “They’re still going to be driven by profit motive.”