Support for slapping a tax on carbon emissions is about as widespread as an environmental measure can get. Environmentalists and progressive Democrats who have long championed a carbon tax have recently been joined by big oil companies and establishment Republicans. It’s the one cause that unites Bernie Sanders and Exxon Mobil.

So why do reliably blue states keep failing to put one in place?

Another carbon tax bill died in Washington state’s legislature earlier this month, the state’s third serious attempt in the past two years. A few days later, lawmakers in Oregon set aside a plan for a cap-and-trade program, scuttling the measure for at least another year. Similar efforts in New England have also gone nowhere. And the pile of failed carbon-tax proposals keeps growing.

But that pile also represents a big experiment. Think of them as trials and errors — many errors — as lawmakers and environmental groups slowly garner public support to make carbon taxes law.

“It’s a cauldron. It’s a mess,” said Jeff Johnson, president of the Washington State Labor Council, a group supporting a new carbon pricing ballot initiative. “To brew up something that most people are going to be satisfied with is really hard to do.”

Carbon taxes are often seen as a common ground climate solution, with supporters ranging across the political spectrum. But that unity disguises an important issue: The nuts and bolts of a carbon tax are divisive enough to make environmentalists go to war with themselves.

That was the story with Initiative 732, a Washington state carbon-tax measure that generated national attention before it went down in flames in 2016. The group behind it, Carbon Washington, tried to appeal to bipartisan support, planning to use money raised from the tax to lower the state’s sales and business taxes. It had endorsements from some Republicans, climate scientists, and, of course, Leonardo DiCaprio.

But in a twist, some progressive and environmental groups — including the state Democratic party — turned against the initiative, arguing it would waste tax dollars. Low-income residents spend more of their paychecks on gas or home heating, and opponents worried the carbon tax might hit them too hard.

The measure soon lost support from progressives who didn’t think it went far enough. On election day in 2016, about 41 percent of voters supported it.

“The environmental community was split down the middle, and the scars are still there,” Johnson said.

That loss sent a message to climate wonks around the state: A simple carbon tax isn’t good enough. Only a kickass carbon tax will do. Since then, lawmakers and climate activists have been playing a long game of trial-and-error, trying to craft a carbon tax that gets enough support from progressives to become law.

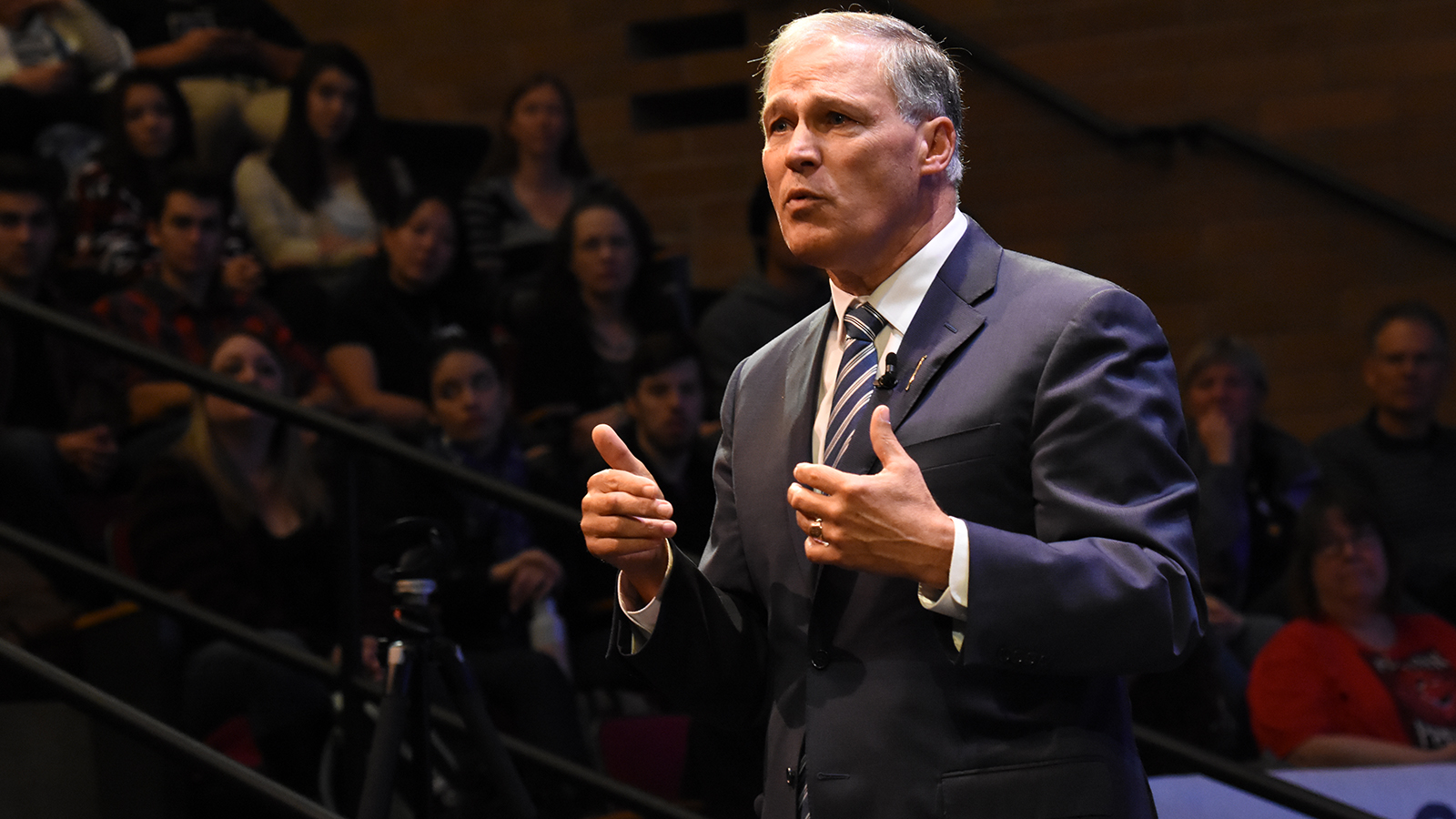

Last year, Governor Jay Inslee asked Washington state’s lawmakers to pass a carbon tax to help fund education. Lawmakers introduced a handful bills that soon fizzled out in the Republican-controlled Senate.

In January, after a special election that flipped the state Senate blue, Senator Reuven Carlyle took a shot. He saw Initiative 732’s failure as an odd sign of hope. If a divisive ballot initiative could even get modest support, a well-designed bill could drum up enough support to pass.

Carlyle’s idea was to use money from the proposed tax to fund sustainability projects, like renewable energy, forest resilience, and assistance for low-income residents. But it split the usual supporters, too. The Quinault Indian Nation, whose reservation is facing the threat of a rising sea, opposed the bill for not being aggressive enough and placing too much of the tax burden on citizens.

“My two passions as a tribal leader for the past decade has been tribal sovereignty and climate change,” Quinault president Fawn Sharp told the Senate Ways and Means Committee. “I’m finding myself conflicted in a bill that has both.”

In the end, Carlyle said the bill lost one Democrat, and fell short of passing on the Senate floor earlier this month.

Down the road in Oregon, the state’s proposed cap-and-trade bill faced opposition from Portland’s electric utility, which said the plan would drive electricity rates too high. Despite support from Democrats, they couldn’t reach an agreement by the end of their one-month session. Leaders agreed to pick up where they left off in next year’s longer session, and also plan to set up a special committee and government office to tackle carbon policies.

None of this has deterred climate hawks. Just a day after Carlyle’s bill failed, the Alliance for Jobs and Clean Energy — a coalition of environment, labor, and social justice groups in Washington — filed a carbon “fee” initiative for the November ballot later this year (cue Hamilton’s “My Shot”).

The Alliance, the same one that opposed Initiative 732, has quietly spent the last two years reaching out to voters and organizations around the state, trying to strike the balance that a successful carbon pricing policy will need.

Their plan would start with a $15 fee on every metric ton of carbon dioxide, a rate which would ramp up over a decade, and would use the revenue to pay for renewables, transportation, climate resilience projects, and efforts to help low-income neighborhoods switch to renewable energy. The proposal exempts some trade-exposed industries, which some fear would be driven out of the state. It already has the support of 29 Northwest tribes, including the Quinault Nation.

If this shot fails, Senator Carlyle said he expects to try again next year. If the initiative succeeds, however, it won’t just be a price on carbon; it will be the result of a multi-year experiment in crafting a recipe for making carbon taxes a reality.