To be, or not to be — that is the age-old question, and civilization today faces its own dire version of it. As the negative social and ecological effects of 150 years of industrialization are becoming impossible to ignore, people are asking whether we can maintain our standards of living. But very few are asking if we should.

Dark days or bright opportunities?

Photo: iStockphoto

There are, however, two contemporary thinkers for whom this question is primal: William McDonough, green architect and designer, and Derrick Jensen, neo-tribal environmentalist and philosopher. They epitomize the vanguard of the new green zeitgeist. They are the elemental planners of a future sustainable society.

Both visionaries are mythically Shakespearean in the quirk, richness, and lyrical beauty of their respective evangelizing characters. But one is Establishment, the other Counterculture. One wears a bow tie, the other wears beads. One comes from the corporate aristocracy, educated at Dartmouth and Yale; the other from working-class Spokane, Wash. and the Colorado School of Mines. One founded three revolutionary companies; the other keeps the company of revolutionaries.

One was named Time Magazine‘s “Hero of the Planet” and is the only recipient of the Presidential Award for Sustainable Development. The other lists more modest encomiums, but to many in the movement, he is every bit as much a hero.

Though these two men share a common belief — that industrial civilization, with its outrageous fortune, is killing the planet, plunging all life into a veritable sea of troubles — they represent two sides of the most important question of our age: Is civilization worth saving?

McDonough says “yes,” and is prepared to suffer the slings and arrows required to make it work. Jensen says “no,” and is prepared, in a manner of speaking, to take up arms and end the whole experiment.

William McDonough.

Photo: Amy Graves/WireImage

The Priest

The priest, by his very nature, derives his faith from pre-existing dogma, which he believes is the One True Way. In the case of William McDonough, the dogma is that technology and human ingenuity can solve virtually any crisis.

Some of McDonough’s more prominent projects include the Lewis Center at Oberlin College, a building that was designed to clean its own wastewater and produce more energy than it consumes, and the famed Herman Miller Furniture factory in Michigan, which boosted productivity so much that the building paid for itself. He is co-creator of the design imprints GreenBlue and MBDC, which have become the harbingers of what McDonough calls “the next industrial revolution.” Instead of an extractive, polluting, single-use “cradle to grave” system, McDonough promises everlasting economic life through his renewable Cradle to Cradle system.

McDonough sees civilization as a good thing, something worth saving, and chalks up our current environmental crisis to a kind of growing-pain mentality. He explains that our industrial childhood — the Industrial Revolution — was predicated on the cradle-to-grave lifecycle. Realizing the limits of this system, and its inherent social and environmental toxicity, he endeavored to create an industrial system that mimics the environment, which takes the principles of nature and applies them to design, and in many respects, integrates the built environment with the surrounding ecosystem.

He has become an archetype for the burgeoning field of “sustainable development,” a traveling missionary proselytizing for the church of technology, bearing the gospel of “zero-impact, carbon neutral, closed-loop smart growth” — a fancy way of saying that he designs buildings that are “like trees” and cities that are “like forests.” He presides over the marriage of technology and ecology, and sends the two off with the church’s blessing to be fruitful and multiply, bearing living, breathing structures that take care of themselves.

Imagine a building, enmeshed in the landscape, that harvests the energy of the sun, sequesters carbon and makes oxygen. Imagine on-site wetlands and botanical gardens recovering nutrients from circulating water. Fresh air, flowering plants, and daylight everywhere. Beauty and comfort for every inhabitant. A roof covered in soil and sedum to absorb the falling rain. Birds nesting and feeding in the building’s verdant footprint. In short, a life-support system in harmony with energy flows, human souls, and other living things.

On the surface, his creed seems noble. But is it even possible?

Certainly on an individual-building scale. But his ultimate goal for civilization is not limited simply to a “paradigm shift” in design. He aspires to a more utopian ideal, totally rethinking how we live and work and prosper.

In McDonough’s world, there would be no “trade secrets,” which allow corporations to legally pollute in the name of profit. His world is a transparent one, where the Constitution still reigns, but “freedom” is not reinterpreted as the right to pollute, endanger, or destroy — and our intentions are not measured by what is not against the law.

“Imagine an economy … that purifies air, land, and water …!” GreenBlue’s website boldly claims. If only we’d listen to him, the growing crowd of acolytes wails, we’d have a chance of saving the planet and ourselves! We can have it all!

Though this priest is preaching hope and harmony, a prophet has appeared who is making people distinctly uncomfortable. He is preaching that the church of sustainability has gone astray by placing its faith in technology and valuing human life above all others. He believes the priests have become corrupt, and has nailed his theses to the door.

The Prophet

His prophesy is of a slightly more acerbic and apocalyptic nature, the man in the dark robe, staff in hand, barking in the marketplace of ideas, warning of the perils of hubris. He has gone into the wasteland of industrial society, with its dams and pavement and cell-phone towers, and returned to the ecosphere bearing tales of the end of days. But unlike the biblical Armageddon, this apocalypse is entirely human-made. It is what he calls the “culture of death” — and what we call industrial civilization.

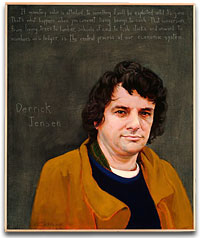

Portrait of Derrick Jensen, part of the Americans Who Tell The Truth collection by artist Robert Shetterly.

Derrick Jensen believes the current “civilization” — a system of sprawl, consumerism, monoculture, industry, war, empire, and a near-total disregard for non-human life that relies on finite resources and is predicated on unlimited growth — is, in a word, insane.

It should be noted that McDonough does not, in principle, disagree with this take on civilization’s path so far. He says quite clearly, “This cradle to grave flow relies on brute force (including fossil fuels and large amounts of powerful chemicals). It seeks universal design solutions (“one size fits all”), overwhelming and ignoring natural and cultural diversity. And it produces massive amounts of waste — something that in nature does not even exist.”

But whereas McDonough believes all we need is faith in technology to persevere, Jensen believes civilization should be brought down as soon as possible in order to save the planet. So much damage has been done, he says, that it’s not a matter of if, but when. The only question becomes, what are you doing to prepare yourself?

The moneychangers in the temple think he’s nuts, not to mention bad for business. But when has the voice of truth ever been welcomed with a drink and a snack?

Jensen’s two-volume, consciousness-shaping testimony Endgame takes as two of its central premises: civilization, especially industrial civilization, is not and can never be sustainable; and civilization is not redeemable. He believes we will not undergo any sort of voluntary transformation to a sane and sustainable way of living. If we can’t get people to stop buying McMansions and SUVs, how on earth are we going to teach them to survive when there is no more food?

Moreover, continued development means less access to land, where access to land means access to self-sufficiency, which means access to life. “Land is primal,” he says. “Everything else is based upon it, even culture. There cannot be only one culture.” Because of this, Jensen claims sustainable development is “an obvious oxymoron,” a “synonym for industrialization.”

Despite the purportedly radical and fatalistic nature of his thinking, Jensen’s analysis might be closer to the truth of our situation than the understandably alluring optimism of McDonough. For all his brilliance, McDonough’s dependence on technology might be — stressing might — that fatal flaw, or at best, the myopia that keeps us spinning our wheels trying to save a system that ain’t no good for us.

This thoroughly depressing idea may explain why, throughout history, the prophets were killed in unspeakable manners for being heretical, while the priests continued to promise a better life for the adherents, even in the face of destitution.

One thing is clear: ideologically speaking, neither would exist without the other. In this case, the natural but unwitting binary system between McDonough and Jensen serves to push the issue of sustainability further than before, folding space, continually challenging the very notions upon which our society rests, and forging ideas for a new, perhaps even better future for life on this planet.

Regardless of the rationality of our need for change, it won’t be easy, or pleasant, and it will probably end up looking a lot different than the way things are now. Revolutions tend to do that.