In the late 1970s, at the tail end of a sweeping push to bring electricity to rural Texas, Alonzo Peeler Jr. struck a series of deals with three electric cooperatives: They could build a coal-fired power plant on the sprawling Atascosa County ranch where his family had run cattle for more than a century. And they could mine the abundant lignite, or “brown coal,” from underneath the property to feed the plant.

To Peeler, now 79, it made sense for a multitude of reasons. Not only would it bring more power generation to the farming and ranching region south of San Antonio, but it would boost the local tax base and bring additional income to his family.

“Looking back,” Peeler says now, “I made a big mistake.”

[grist-related-series]

Peeler, who grew up on the now 25,000-acre ranch and dropped out of college to come home and help run it, thought the contract he signed ensured the cooperatives would promptly restore his land as soon as they were done mining it. In fact, the agreement required them to begin restoring the land within six months of abandoning excavated areas.

That wasn’t just in the contract, either: State and federal laws require companies to “reclaim” mined land, a process in which companies restore land to its former condition so that it can be used again for grazing cattle, building homes, and businesses or recreation.

San Miguel Electric Cooperative, which took over operations of the plant and mine — and the Peeler lease agreement — in 1978, ceased mining on the family’s ranch in 2004 and moved on to other private land close to the power plant. But 15 years later, after paying the family millions of dollars to mine lignite on the ranch, San Miguel has only fully restored about a fifth of the land it disturbed. What’s more, the Peelers say the condition of the land that the cooperative has yet to restore is deteriorating.

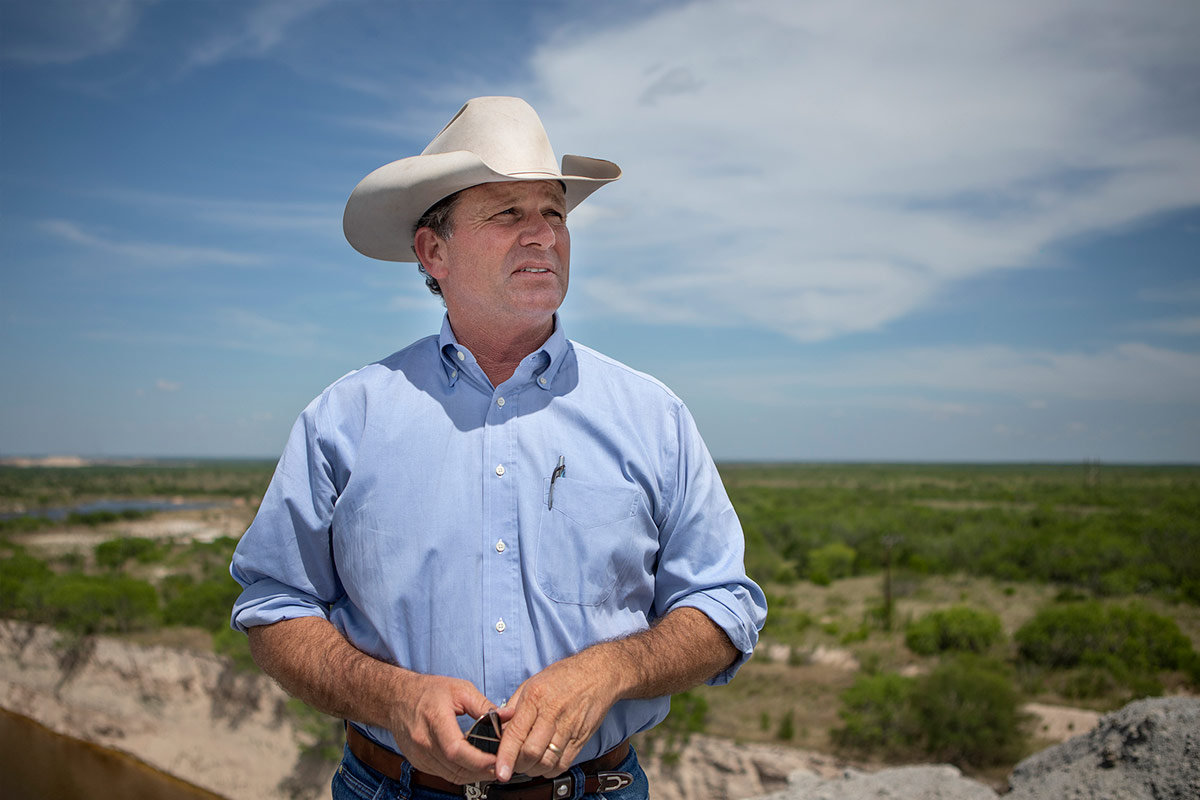

Alonzo Peeler Jr. grew up on the South Texas ranch and later inherited it from his father. Miguel Gutierrez Jr. / The Texas Tribune

“It’s like a death in the family,” said Jason, Alonzo Peeler’s son, who took in the full extent of the damage a few years back while flying his Piper Super Cub airplane over the ranch.

Throughout the 4,000-plus acres of Peeler property that San Miguel mined over a quarter century, it has buried powdery gray coal ash — a byproduct of burning coal at its nearby power plant — in deep mine pits and piled it into towering mounds. The power plant generates 1.8 million cubic yards of the substance, which contains toxic heavy metals that can leach into the soil and groundwater, every year. (That’s more than half the volume of Egypt’s Great Pyramid at Giza.) And the family claims that San Miguel hasn’t properly managed its disposal.

The family also claims the cooperative has tainted its land by improperly discharging millions of gallons of wastewater from its power plant onto parts of the ranch it had never leased.

“The problem probably started right away, but it took 25 years for it to become obvious,” the elder Peeler said.

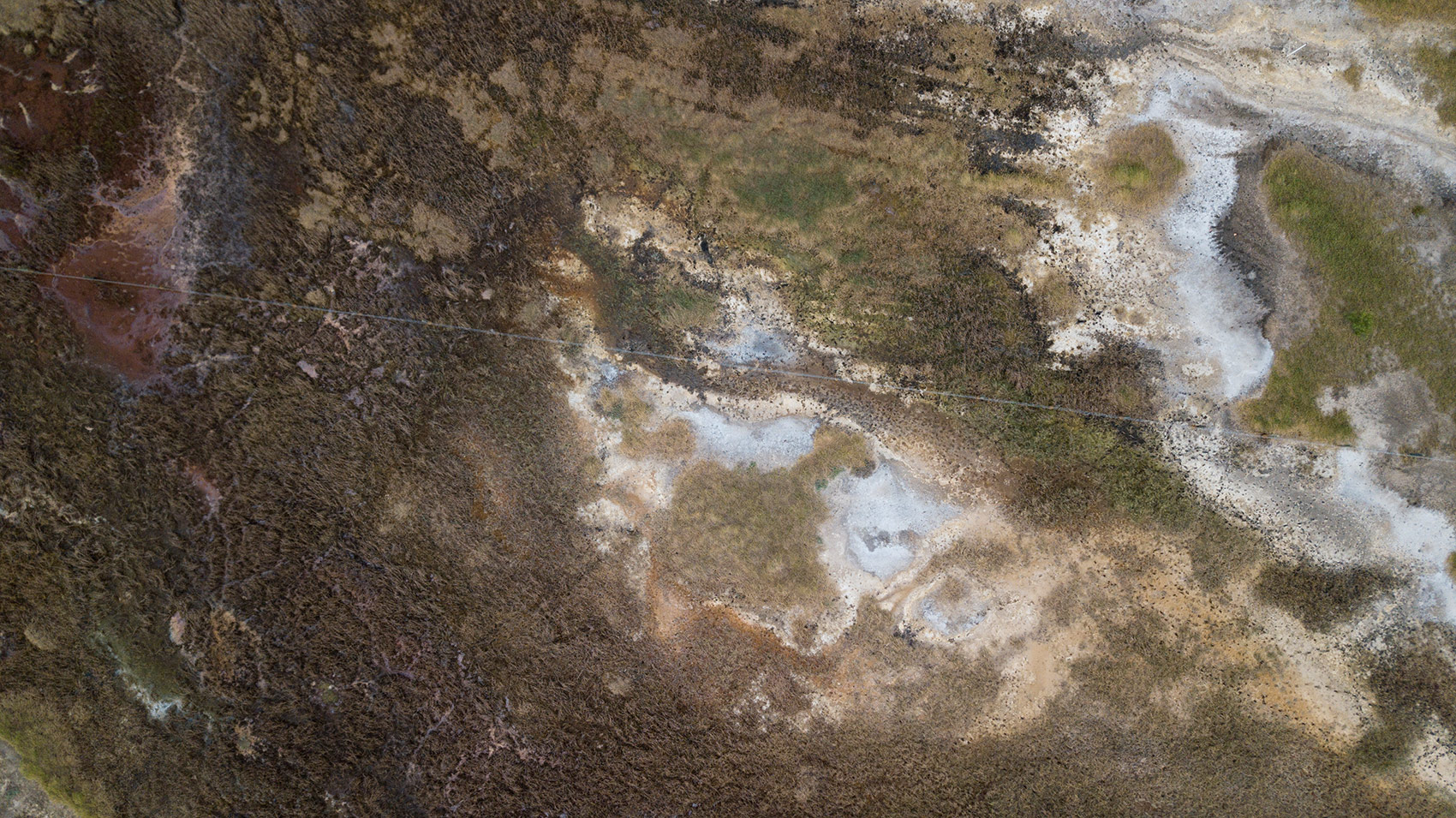

The family says the damage is revealed in persistent sprawling wet spots on the property — even though the rural area about 50 miles south of San Antonio is always in and out of drought — and moonscape-like dead zones where scrubby grass and hardy mesquite trees once flourished.

And the Peelers point to water and soil testing done on the former mine and around the power plant by environmental consultants they hired in late 2017. It found that the soil and surface water contained levels of arsenic and other contaminants considered unsafe for human exposure; the surface water also contained levels of calcium and sulfur considered unsafe for livestock consumption.

Luckily for the family, the testing showed that contaminants didn’t reach the deep water wells the Peelers used to drink from and water livestock. In January, an analysis of testing data from 16 Texas coal plants by an environmental nonprofit found the groundwater just beneath San Miguel’s power plant was more contaminated than any of the others.

In a written statement, San Miguel said it is discharging wastewater properly under its state-approved permits and that it’s in compliance with all environmental regulations meant to protect water quality. It noted that two different state agencies have inspected its discharge operations and found no violations. And it said the Peelers agreed to let it dispose of coal ash on the land. (Public records show the cooperative has been fined by the state of Texas in recent years for releasing wastewater into a creek tributary and allowing sediment from its mine to run off onto Peeler property.)

As for the dead zones the Peelers allege have taken over their property, the cooperative said they could simply be the result of naturally-occurring saline soils in South Texas as well as the Peelers’ use of herbicides sprayed from helicopters.

“San Miguel has taken great care in operating as a careful steward of the land — land that we care about and that is part of our commitment to provide South Texans with safe, dependable and affordable electricity to power their homes and businesses,” the cooperative said in a statement. It added that it has begun restoration on all but 20 acres of the land.

Last summer, the Peelers tried to kick San Miguel off their property, saying their efforts to get the cooperative to accelerate restoration had been unsuccessful. San Miguel promptly sued.

A moonscape-like dead zone sits just outside the fence line of San Miguel Electric Cooperative’s coal-fired power plant on land the cooperative leased from the Peeler family. In January, an analysis of San Miguel’s own testing data found groundwater around the plant was the most polluted of 16 coal plants in the state. Miguel Gutierrez Jr. / The Texas Tribune

As the dispute was heating up early last year, the Peelers took their complaints to the Railroad Commission of Texas, the state agency that regulates coal mining.

But Jason Peeler said a commission inspector who visited the ranch last year and surveyed the mounds of coal ash “told us that he would let his kids play in [it], it was no big deal.”

The inspector didn’t see what the problem was, Jason recalled. “I told him, ‘You’re looking at it.’”

[jumbo-content]

[/jumbo-content]

The inspector was from the Railroad Commission’s Surface Mining and Reclamation Division. Since 2016, the division — which consists of about 40 employees who work in a state building in downtown Austin — had been led by Denny Kingsley, a former coal executive who had retired from a 36-year career in the industry a few months before being hired to help regulate it.

Five current and former division staffers who worked under Kingsley and/or his second-in-command, Travis Wootton, also told Grist and The Texas Tribune that both men helped mining companies throughout Texas avoid penalties and minimize their reclamation responsibilities, perpetuating what the employees said was a pattern of pro-industry behavior among division leadership going back years.

A yearlong investigation by Grist and The Texas Tribune also found that:

- Kingsley and Wootton on several occasions overruled staff when they identified problems with mining companies’ proposed reclamation plans or flagged violations. (Public records show both men were later fired after a human resources investigation found they retaliated against staffers who “voiced professional opinions that appear to be adverse to industry.”)

- The Railroad Commission has increasingly allowed companies to do the bare minimum when cleaning up their mining sites, approving a growing number of requests to apply the least stringent restoration standards for their shuttered mines — regardless of whether companies can justify the lower standard.

- Receiving permission from the state to apply that lower standard, which is for land intended for industrial or commercial use, can save companies millions of dollars and years of reclamation and monitoring responsibilities — and allow them to avoid testing soil for the harmful pollution common at mine sites.

- The result of these practices is that there are potentially thousands of acres across Texas contaminated with toxic chemicals, which can leach into the groundwater and soil and endanger people’s health.

“The regulations are to ensure that once these lands are disturbed by mining, that they are put back as it was or better than,” said Joe Collins, who worked in the reclamation division for eight years and retired from the Railroad Commission in August. “A lot of our practices through the years allowed the mining companies to do not very good reclamation and turn back land to some of the landowners that was inadequate, or not as good as it was before, due to the fact that it costs too much to do the right thing.”

The findings come as coal companies and power generators across the country are doing everything they can to cut costs amid stiff competition from cheap natural gas and a flourishing renewable energy industry. In the past decade, roughly half of all mines and more than 546 coal-fired power plants closed despite President Donald Trump’s efforts to resuscitate the industry. With less mining taking place, cash-strapped companies are struggling to pay for mine restoration.

After reviewing the findings of the Grist/Tribune investigation, Joe Pizarchik, the former head of the federal Office of Surface Mining Reclamation and Enforcement during the Obama administration, said his former agency should investigate whether the Railroad Commission is following federal standards for mine reclamation.

“OSMRE should conduct an oversight review,” Pizarchik said, adding that if the agency concludes that the Railroad Commission failed to implement federal law, it should expand its investigation and “look to see whether there were [other] similar failures.”

Even though the commission ousted Kingsley and Wootton for going after staffers who raised red flags about mine sites across Texas, the former employees say there is no indication that the commission is reviewing the division’s previous rulings on mine reclamations or revisiting companies’ justifications for requesting the most lax reclamation standard.

San Miguel Electric Cooperative has piled a mound of coal ash — a byproduct of burning coal that contains toxic heavy metals — on land it leases from the Peeler family. Its 400-megawatt power plant sits in the background. Miguel Gutierrez Jr. / The Texas Tribune

The Railroad Commission declined to answer questions about whether it plans to review Kingsley and Wootton’s decisions, saying it doesn’t discuss personnel matters. Nearly a year after the two resigned in lieu of termination, the agency hasn’t replaced them and the agency’s general counsel is leading the reclamation division.

In an interview earlier this year, Kingsley — a tall, white-haired grandfather of seven — told Grist and the Tribune that he had no concerns about subpar restoration at the mines under his leadership. Kingsley said he would never have done anything to tarnish his legacy.

“I really came there to try to do the right thing, treat all groups fairly and openly and transparently,” he said. “But sometimes people just get their feelings hurt because you don’t see it their way.”

Grist and the Tribune’s attempts to reach Wootton for comment were unsuccessful. But during a deposition taken earlier this year in the Peeler-San Miguel lawsuit, he said he was surprised by the commission’s decision to terminate him and didn’t believe there was a basis for the allegations of industry friendliness that sparked the human resources investigation.

“I believe it’s a misunderstanding,” he said. “Perception is perception.”

Federal agency missing in action

Though it’s famous for its oil and gas production, Texas is actually the nation’s seventh-largest producer of coal, with 29 surface strip mines across the state that employ more than 1,600 people.

Surface — as opposed to underground — coal mining became popular in the 1960s as technological advances made it cheaper than tunneling underground. The practice quickly became notorious for how it reshaped the landscape: In Appalachia, mining companies scraped away mountaintops, bulldozed forests, and buried streams under mounds of earth and mine waste. The toxic heavy metals found in coal permeated the soil and water.

The country’s patchwork of state-level mining regulations proved to be inadequate for the scale of this new type of mining, and under mounting public pressure, Congress passed the Surface Mining Control and Reclamation Act in 1977, creating a federal fund to help pay for cleaning up abandoned mines and requiring companies, when they applied for mining permits, to submit plans for how they would restore land.

Those reclamation plans had to detail how companies planned to smooth over scarred land, replenish vegetation and meet federal water quality standards — and they could add millions of dollars to the cost of every new mine. A new agency, the Office of Surface Mining and Reclamation, or OSMRE, was given responsibility for enforcing all the new regulations.

But everyone involved, from mining companies to environmental groups to state regulators, soon realized that important parts of the law were too vague. For example, it stated that reclamation had to happen “as contemporaneously as possible” but didn’t establish any timeline.

As a result, land mined decades ago still hasn’t been restored. In the Powder River Basin in Montana and Wyoming, for example, six mines that have been operating for almost four decades or more have had zero acres fully reclaimed.

In its 2018 annual evaluation of reclamation efforts in Texas, OSMRE said the state’s coal companies have historically been slow to reclaim coal mines — and noted a concerning increase in the time it’s taking companies to finish the work.

“The recent significant economic downturn in the general coal industry may have been a factor; but, if so, OSMRE would expect to have found [the Railroad Commission of Texas] addressing problems with contemporaneous reclamation,” the report said.

Still, OSMRE’s assessments of the Railroad Commission’s work have generally been laudatory. Year after year, it’s found that the state agency has issued permits according to federal guidelines and successfully tamped down on environmental impacts from mining. It also has handed out awards to the commission for effectively reclaiming mines that companies have abandoned.

But critics say OSMRE’s glowing reviews of the Railroad Commission conceal the fact that the federal agency is perpetually missing in action, rarely holding states or mining companies accountable. While it has the power to take over a state’s reclamation program if it finds a state isn’t doing the job, it has only done so once — when coal-rich Tennessee repealed its entire state mining law in 1984.

In reality, the federal agency has never had the budget to directly oversee mining companies at the state level, said Peter Morgan, a senior environmental attorney at the Sierra Club based in Denver.

“The problem is the states know that’s an empty threat, so they often do the bare minimum,” Morgan said.

OSMRE conducts random inspections of mines, and when it finds violations, they’re often referred to the state agencies to follow up. From 2010 to 2018, it conducted 64 inspections in Texas and found seven violations. It referred all seven to the Railroad Commission; it’s unclear whether the citations led to fines, although typically the commission gives companies time to fix problems and rarely issues hefty penalties.

The Peelers family says wastewater discharged from San Miguel Electric Cooperative’s coal-fired power plant has damaged its land. The cooperative says it is operating according to its state-issued permits and that the dead zones on the ranch could be due to the Peelers’ use of herbicides and pockets of salty soil that are common in the region. Miguel Gutierrez Jr. / The Texas Tribune

The coal ash conundrum

The Peelers are a wealthy, politically connected family that is well-known in South Texas: Jason Peeler was appointed by former Governor Rick Perry to serve on a local water conservation district board and has held leadership positions with major agricultural lobby groups.

Despite their political clout, the Peelers say it appears the state and federal agencies that are supposed to protect the land — and Texas landowners — are letting coal companies avoid having to clean up their mess.

[protected-iframe id=”d240a12f0140b16e056fdb5f2c822270-5104299-29763145″ info=”https://graphics.texastribune.org/graphics/reclamation-station-2019-08/san-miguel-satellite/” width=”100%” height=”600″ frameborder=”0″]

Since mining ended in 2004 on the Peeler property, San Miguel has been allowed to bury more than 8 million cubic yards of coal ash — enough to fill the Dallas Cowboys’ football stadium more than twice over — on about 300 acres. The practice — called “beneficial use” — is common but controversial and one the EPA identified as environmentally risky in 2015, when President Barack Obama was in office.

Pizarchik, the former federal regulator, was critical of the practice, saying beneficial use “has basically functioned as a euphemism for virtually unregulated disposal” of coal ash. It’s the responsibility of state mining regulators to ensure coal ash doesn’t contaminate water sources when buried at mine sites, he said.

San Miguel Electric Cooperative has piled a mound of coal ash, which contains toxic heavy metals, on land that it leases from the Peeler family. Miguel Gutierrez Jr. / The Texas Tribune

The environmental consultants hired by the Peelers in 2017 said the contamination they documented was linked to coal ash. “It should be noted that the extremely large waste ash stockpile” on the land “has not been buried or covered, and can easily mix with the surface soils,” the consultants wrote.

The toxic heavy metals the consultants detected at elevated levels in the surface water — including arsenic, cadmium, and lead — are all known to be present in coal ash.

A separate report by the Environmental Integrity Project, a Washington, D.C.-based nonprofit founded by former EPA officials, identified three unlined — or inadequately lined — coal ash waste ponds on the Peeler property and an ash landfill near the power plant, which is surrounded by the Peeler’s land, as the source of the contamination. For cadmium, a known carcinogen, the levels were up to 130 times higher than the EPA’s safety threshold.

The findings were hard to dispute: The nonprofit’s analysis was based on San Miguel’s own groundwater sampling data that it was required to report to the EPA under a 2015 rule the Obama administration enacted to minimize the dangers of coal ash contamination — a rule the Trump administration is now trying to unwind.

The Peelers have sought assistance from the EPA, but the family’s Austin-based attorney, Mary Whittle, said the agency stopped responding to her requests to investigate San Miguel’s actions late last year. The EPA declined to comment, citing ongoing litigation.

In public and written statements provided to Grist and the Tribune, San Miguel has acknowledged contamination of groundwater at the plant and said it has installed “numerous wells beyond the boundary of the power plant to determine the nature and extent of the contamination.” But it also has said it wasn’t necessarily to blame.

“The presence of certain observed constituents could be due to naturally occurring conditions or other activities unrelated to San Miguel’s operations, such as oil and gas activity or the use and disposal of agricultural and other chemicals that have taken place on the Peeler Ranch,” the cooperative said in an FAQ it compiled in response to the Environmental Integrity Project report.

It also said it routinely submits water monitoring data to the Railroad Commission and the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality, the state’s environmental regulatory agency, to prove that its wastewater discharges are in line with the permit requirements.

Jason Peeler walks up a coal ash mound on his family’s property. San Miguel Electric Cooperative’s power plant generates 1.8 million cubic yards of coal ash every year, some of which the cooperative has deposited on the Peelers’ land. Miguel Gutierrez Jr. / The Texas Tribune

Online records dating to 1995 show that TCEQ has penalized the cooperative once for water pollution: a fine of $26,564 in 2016 for spilling about a half-million gallons of wastewater from coal ash ponds into a tributary of a nearby creek. The wastewater violation was one of seven times the agency has fined San Miguel since 1995; the rest were for unauthorized air pollution emitted from the power plant.

As part of a TCEQ program to protect the environment and human health, San Miguel conducted a survey and didn’t identify any water wells being used for drinking within a half-mile of the contamination. Martha Otero, a spokesperson for the agency, said that it plans to propose state regulations to oversee coal ash disposal in November and, once they are finalized, “will take appropriate actions to monitor compliance at the 17 coal plants located in Texas, including pursuing enforcement for documented violations of the rule requirements.”

An industry-friendly culture

Five current and former employees of the Railroad Commission’s surface mining division told Grist and the Tribune that staff members have long been worried about the level of influence the mining industry exerted on the agency.

Collins, a hard-nosed inspector who worked in the Railroad Commission’s surface mining division between 2004 and 2012, said he remembers catching San Miguel employees draining water from a mining pit into a nearby creek during a routine inspection of its mine. He knew the pit had high levels of the mineral boron — which can decrease fertility in humans — so he ordered the cooperative to stop the work, then collected water samples that he planned to send to a lab for testing.

But when he returned to the office, he received an order from his supervisor that upset him.

“I was told, ‘No, you will not analyze [the samples],’” Collins recalled. Another former reclamation division employee, who requested anonymity for fear talking to the press would affect their current job, corroborated Collins’ recollection of the incident.

It was one of the many favors Collins said he saw San Miguel receive when he worked in the surface mining division. “There have been several incidents that San Miguel has lawyered up and skated the process,” he said. “They found favor with somebody.”

Collins later transferred to the commission’s oil and gas division before retiring from the agency in August.

San Miguel refuted both of Collins’ claims that it knowingly allowed contaminated water to escape into a creek and received favorable treatment from the agency. “We fundamentally disagree with that implication and, in fact, believe that San Miguel has been heavily regulated by the Railroad Commission and given no relief whatsoever from the stringent requirements of the program.”

Mark Schlimgen, Collins’ supervisor at the time — who Collins alleges gave him the order not to analyze the water samples — could not be reached for comment.

Collins and other current and former employees in the division found their employer to be deferential to mining companies’ concerns and singled out Wootton as often siding with industry. Wootton had joined the agency in 1990, straight out of college, and worked his way up to the second-highest position in the department over the next few decades.

Staffers who worked with him said in their view, Wootton gave more weight to the opinions of mining companies over his own staff, who were technical experts. One former staffer recalled overhearing Wootton on the phone with mining companies, explaining how to gain approval for reclamation plans as quickly as possible — even if those proposals didn’t meet state regulations. He would, for instance, advise companies to submit piecemeal changes to their mining permits so that when it came time to renew them, there would be less to scrutinize, and the companies could request approval without a public hearing.

“Bottom line, whatever could be cooked up that would help an application make it out the door with an approval, he was definitely into the idea,” said the former employee, who requested anonymity for fear it would affect their current employment.

The former employee also recalled going into meetings with Wootton and the previous division chief, thinking they were all on the same page about deficiencies in a company’s proposed reclamation plan. The employee would quickly find out that the two supervisors had worked out a deal with the companies that would let many of the problems slide.

Current and former staffers said their concerns about the division’s coziness with industry deepened in 2016 when the agency hired Dennis Kingsley to lead the department. Kingsley had no prior government experience, but he had a long career in coal mining.

After receiving a civil engineering degree from Tennessee Technological University in 1980, Kingsley held various positions at Luminant’s Big Brown and Martin Lake mines in East Texas before becoming general manager and president of operations at Texas Westmoreland Coal Company’s Jewett mine — a job he left after the company closed the site. Kingsley continued to golf with a San Miguel reclamation supervisor after joining the commission — even as the company had a permit application pending before it.

“Both [Wootton and Kingsley] were very pro-industry to a fault,” the former employee said, adding that “I saw that sort of behavior from Travis long before [Kingsley] ever showed up.”

Kingsley and Wootton have taken issue with that characterization. In the deposition taken in May as part of the Peeler-San Miguel lawsuit, Wootton denied that he was more favorable to industry and said he had “no idea” why his employees made that claim.

In a written response to questions from Grist and the Tribune, Kingsley said the main reason he was hired was to figure out how to tackle a huge backlog of mining permit applications and revisions to reclamation plans. “Many of these projects had statutory deadlines that were being ignored by staff,” he said.

One initiative he said he spearheaded involved having staff map the entire permitting process and put it online so companies could better understand the complex procedure. “We often used the phrase that we wanted to be ‘industry friendly,’ which was intended to reflect our goal of being clearer in what we needed and being more efficient in our review process,” he said.

The staff didn’t always embrace such reforms, Kingsley said, and some employees “pushed back at an effort we made to better communicate with [coal companies]” and saw the shift as too accommodating to industry. “That may be true,” he added, “but it did not compromise the regulations that we were charged to enforce.”

He added that the allegation that “we cut deals with industry and surprised staff in meetings with a closet deal is absolutely untrue.”

Top managers forced out

In 2015, agency inspectors twice fined San Miguel after discovering that the cooperative had allowed sediment from its mine to flood Peeler property. But when an inspector documented a third incident the following year — about two months after Kingsley had been hired — two former employees said Wootton, who was then the applications and permits manager, asked the inspector not to fine the cooperative for violating the terms of its permit.

Instead of writing up a notice of violation (or NOV), issuing a fine, and requiring the cooperative to stop the sediment from running offsite, the agency quietly dropped the formal enforcement action and asked the cooperative to conduct repairs. It was a significant decision: A third violation would have meant a higher fine, but more importantly, it would’ve established a pattern of behavior likely to alert federal regulators — who received a copy of every mine inspection and routinely reviewed enforcement actions.

Ramona Nye, a spokesperson for the Railroad Commission, said that protecting public safety and natural resources is a “top priority” at the agency and that “all operators are required to be in compliance with state and federal coal mining regulations.”

Another former division employee, who requested anonymity for fear that speaking out would lead to retaliation at their current job, said that federal regulators would’ve likely included the violation in an evaluation report published online, potentially attracting attention from the media and the public.

“You don’t want the federal Office of Surface Mining to come in,” the former employee said. “It changes everything.”

But Kingsley said that the allegation that Wootton — who reported to him at the time — directed a staffer to not fine San Miguel a third time, was false, adding that “writing or not writing [an NOV] was the responsibility of the Inspector.”

“Additionally,” he said, “any practice found to be an environmental threat was treated as an automatic NOV.”

Wootton could not be reached for comment.

The tension between Kingsley and Wootton and their staff eventually came to a head last fall when an employee in the surface mining division complained about Kingsley to the commission’s human resources department, which launched an investigation. The agency declined to provide a copy of the complaint and files from the investigation, citing attorney-client privilege. As a result, the exact details of the complaint are unclear, but a memo detailing the employee’s concerns states that Kingsley had threatened to demote an employee.

Then, while the investigation was still underway, Wootton attempted to reassign two employees — including the person whose complaint had led to the investigation — to another section within the surface mining division during a meeting and told staffers they were not allowed to complain to anyone about the change. The two employees did not respond to interview requests from Grist and the Tribune, but an internal memo documenting the agency’s decision to fire Wootton noted that staff members were concerned about negative treatment “because they voiced professional opinions that appeared adverse to industry.”

The investigation concluded that Wootton’s attempt to reassign the employees and Kingsley’s effort to demote the other employee “at a minimum created an appearance of retaliation and/or actual attempted retaliation against staff for voicing concerns.”

According to records outlining the findings of the investigation, “Staff members otherwise do not feel comfortable expressing professional opinions and/or are anxious about or unsure how to perform their jobs.”

The agency issued letters of termination for cause to both men and gave them the option to resign, allowing Wootton to claim pension benefits.

Kingsley said he was sensitive to the fact that he came to the agency as an “industry guy” and tried not to let that dictate his management style. As far as he could tell, he said, he was doing things by the book, and only a few employees seemed unhappy with his decision-making.

“I have no hard feelings whatsoever,” he said. “Politics is a hard thing to navigate.”

He described being forced out as a shock and said the agency never gave him a reason. The commission declined to comment on personnel matters.

Since leaving the agency, Kingsley has set up a consulting firm. This spring, a state senator invited him to the Texas Capitol to testify in favor of a bill that would have allowed the Railroad Commission to study whether quarries and mining pits can be turned into drinking water reservoirs.

In his public remarks, Kingsley didn’t disclose that he had been forced to resign from the agency just a few months earlier.

‘A Railroad Commission problem’

In June 2018, the Peelers’ lawyer notified San Miguel Electric Cooperative that its lease with the family, which allowed it continued access to the former mine, was set to expire in a few weeks and that it would need to vacate the property. The cooperative quickly sued the family and then went one step further — it tried to condemn thousands of acres of its ranch.

San Miguel argued that it needed to seize more than 7,000 acres so it could continue restoring the old mine and keep its power plant running. In court filings, the cooperative said that it needs access to several roads that connect its coal plant and other private property where it’s still mining. Being denied access to the Peelers’ ranch, the cooperative said, would hinder its ability to operate the power plant, threatening the state’s electric grid.

The Peelers have tried to kick San Miguel Electric Cooperative off their property, claiming the cooperative hasn’t fulfilled its obligation to restore land damaged by mining. But San Miguel says it needs access to the haul roads on the Peeler property to get to its coal plant and other private land nearby where it’s mining lignite. Miguel Gutierrez Jr. / The Texas Tribune

“The argument that they have to condemn the Peeler Ranch in order to reclaim it is pretty nonsensical,” said Whittle, the Peeler’s attorney, adding that the family resorted to ordering the cooperative off its property only after San Miguel failed to reclaim the land as required in the contract.

San Miguel said it would prefer not to condemn the Peelers’ land and wishes to “work cooperatively with the Peelers.” In trying to address the Peelers’ complaints that reclamation isn’t happening quickly enough, the cooperative said it tried to speed up removing waste from a pit, but because the Peelers blocked access, it hasn’t been able to follow through.

“We have every interest and desire to move ahead with addressing this issue to everyone’s satisfaction and as quickly as possible,” the cooperative said in a statement.

The family countersued last year, alleging San Miguel had “turned significant portions of the Peeler Ranch into a toxic dump, knowingly and intentionally exposing the Peelers to long-term, if not perpetual, environmental liability.”

Last year, a Texas judge ordered the Peelers to allow San Miguel access to the property while the lawsuit plays out and ordered the cooperative to notify the family of any plans to dispose of coal ash or discharge wastewater. In June, San Miguel promised to cease both activities as part of a voluntary agreement with the family. The case is set to go to trial next summer.

Standing on a patch of withered ranchland on a hot afternoon in late April — with vistas of coal ash on the horizon — Jason Peeler said that San Miguel was to blame but that ultimately the state agency overseeing mining is responsible.

“This is a Railroad Commission problem,” he said.

This story is a collaboration between Grist and The Texas Tribune, a nonprofit, nonpartisan media organization that informs Texans — and engages with them — about public policy, politics, government, and statewide issues. Learn more at texastribune.org