The Great Warming aims to do what other climate-change books, TV shows, and films haven’t. In lieu of purely scientific or data-based persuasion, it appeals to viewers’ sense of spiritual and moral responsibility. On that level, it succeeds.

Debuting in American theaters on Nov. 3 but already making the rounds in the country’s churches, the film takes regular folks and lets them talk about climate change, attempting to appeal to the emotions of, well, regular folks. There’s Danny Duet down in Louisiana talking about the changes he’s seen on the bayou, the rising waters and receding dry land. There’s Rev. Gerald Durley trying to explain global warming to a pack of elementary-school children. There’s even a dramatized reenactment of a woman being rushed to the hospital during an asthma attack, after which attending physician Jean Zigby pauses to address the camera: “I’m worried that I’m going to have my daughter in 10 years from now looking up at me and saying ‘Dad, why didn’t we do anything? We knew it was coming. We had all the information. Why didn’t you do something?’ And I don’t have an answer to that.”

The documentary (see a preview below) starts out with an eerie child’s voice singing the familiar “It’s raining, it’s pouring,” with the haunting addition of “the temperature is soaring,” over equally eerie images of said child. Really, one of the major things the film has going for it is children, when they’re not being creepy. That’s something An Inconvenient Truth could have benefited from, were it not focused entirely on a middle-aged white guy presenting a digital slide show. When you’re talking about humans causing global warming, it helps to have humans in the movie. Especially small humans.

The Great Warming shows a child in Peru who lost her brothers to cholera after El Niño floodwaters contaminated the water supply. It shows kids in a Maryland elementary school issuing “tickets” to faculty members who fail to turn off their computers at night. It has a pleasantly uncomfortable scene in which an awkward young evangelical teen asks her church-group leader, “Don’t the tree-huggers put nature above God?”

The film combines a few tugs at your ventricles with an impressive breadth of topics relating to climate change — the causes, the implications, the political context — and a lot of “ain’t it cool” technological advances. Based on Lydia Dotto’s 2000 book Storm Warning: Gambling With the Climate of our Planet, the film version was first a three-part series totaling 138 minutes, designed for Canadian television.

The conversion from serial format to single-feature length is evident. The edit tries to fit too much in and becomes disjointed at times — it jumps from asthma rates to (wait, what?) former CIA director James Woolsey talking about terrorism to (oh, yes!) the evangelicals. And then on to cage aquaculture in Bangladesh.

At some points the film borders on bizarre, like when the filmmakers head to New Hampshire to hang out with the editor of The Old Farmer’s Almanac, or down to New Orleans, where in a scene shot in 2003, a street tarot-card reader predicts hurricanes and drownings in the city. It’s narrated by ’90s rocker Alanis Morissette and guy-who-appears-in-movies Keanu Reeves, whose monotonic presence in any film can’t easily be forgiven. It’s not clear whether he had ever heard the words “climate change” before reading them on camera in a stilted deadpan.

The film has been making its way around the evangelical church scene since this past summer, accompanied by voter guides and eco-sermons. Paul de Vries, a board member of the National Association of Evangelicals, has called the film “a must-see for Bible-believing people.” About two-thirds of the way in, a chunk of the film focuses on the green movement among evangelical Christians. It starts out with some of the basic “change-your-lightbulbs” kind of advice, but then, impressively, draws the lesson out to the greater political context.

Though not explicitly political in nature, the film doesn’t avoid politics, either. It self-consciously tries to appeal to the nearly 50 percent of the GOP base that considers itself evangelical. It tells folks that not only does it matter what they do in their daily life, but who they elect matters, too.

“If the largest population group in the Republican Party were to say, ‘We want you to take, as leaders in the Republican Party, leadership on climate change, on clean air, on pure water … if evangelical Christians were to say that, I dare say the Republicans will listen,” Richard Cizik, vice president of governmental affairs for the National Association of Evangelicals, says in the film.

William Nitze, chair of the Climate Institute, sums up the film’s motives rather neatly: “It is not going to be dollars and cents, in the end, that is going to move people on this issue. It’s going to be the perception that their own short-term selfishness is destroying the world and that as spiritual beings, they have a duty not to be so selfish.”

And though I don’t support most things that involve Keanu Reeves, I do support a film that can reach the vast, untapped wealth of nice folks who need this type of warm invitation (pun intended!) to join the ranks of climate-change activists. Watching The Great Warming may not boost your scientific acumen, but it will make you feel all squishy inside about your ability to create change.

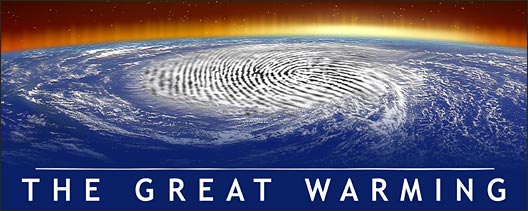

Watch a scene from The Great Warming: