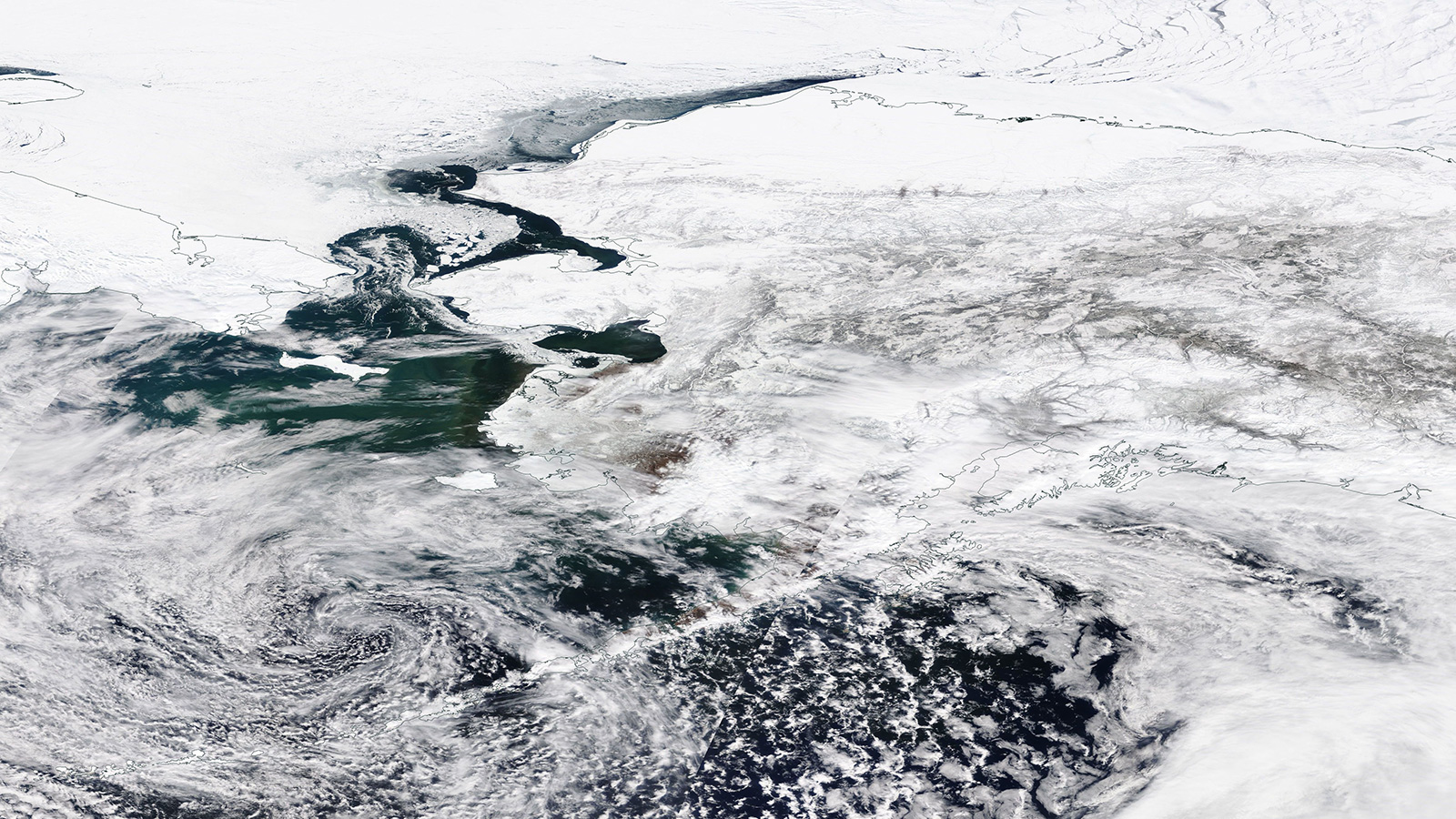

On Alaska’s West Coast, the feeble April sun is shining this week on a fresh spot of open water. The sea ice found there for ages every spring is gone.

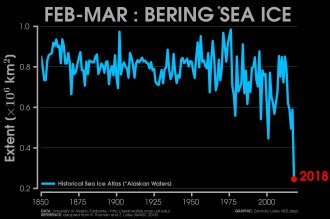

Ice in the Bering Sea, the narrow body of water between Russia and Alaska, has dropped to its lowest springtime level since at least 1850. In all that time, no other year has come close. After a winter filled with unusually high temperatures, sea ice now sits at less than 10 percent of what could previously be considered “normal”.

“We’ve fallen off a cliff,” said Rick Thoman, a climatologist at the National Weather Service in Alaska, in a tweet.

Coming on the heels of the warmest winter in the Arctic since records began, the loss of ice is at once predictable and shocking. The ice disappears every summer but never so early. It’s the latest sign of what scientists have been calling the New Arctic — a novel landscape that’s replacing the ecosystem that has existed at the top of the world for millennia. Arctic temperatures are rising at a rate twice that of the global average, which means that for the foreseeable future, the region will continue to showcase the effects of climate change at their extreme, with repercussions across the world.

For residents of western Alaska, this new record hits home. Waves on the Bering Sea are crashing into their houses and ports with unusual ferocity this spring. Huge ocean storms — commonplace at the far northern reaches of the Pacific — now bring waves the size of five-story apartment buildings.

In late February, an ocean storm ravaged the community of Little Diomede Island, knocking out power and damaging the town’s water treatment plant. The lack of protective sea ice means even storms of average strength hit the town of Shishmaref hard this winter, even as locals there have decided to permanently relocate further inland, away from the encroaching sea.

For native people around the Bering Sea, climate change is already an an existential threat.

“The sea ice loss has disrupted community’s timeframes, schedules, and areas where we normally hunt ice-associated marine mammals,” said Austin Ahmasuk, a community advocate for the Bering Straits Native Association, in an email to Grist.

Hunts for walrus, whales, and seals have historically provided native people in western Alaska with an ample source of food, but warmer weather has threatened catches. In some places, walrus catches have plummeted. Ahmasuk says that few communities have been spared the new reality of an ice-free spring.