Two years ago, Wilmar, the biggest palm oil company in the world, made a commitment to halt deforestation. That set the dominoes tumbling: Other companies followed suit, until every major buyer of palm oil was on board. But it didn’t stop there. Other big agricultural commodity traders pushed the bar higher by promising to end deforestation not just as it related to palm oil, but across all their supply chains. Key logging corporations also pledged to stop clearing new land.

Last year, I wrote a hopeful piece about the origins of this sea change. Surely this meant good things for tropical forests, particularly in Indonesia, the world’s biggest producer of palm oil, and home to over 40 million hectares of species-rich primary forests — an area the size of Montana.

Then I watched in dismay as a particularly awful fire season torched forests across Indonesia. Forest fires, most lit to clear land, covered the region in a choking haze and produced more greenhouse gases each day than the entire U.S. economy. It may be the worst ongoing climate change crisis. In the parched summer of 2015, fires consumed 2.6 million hectares of forest and farmland in Indonesia.

The most pugilistic environmental groups claimed that the very companies that had committed to ending deforestation were secretly encouraging the burning so as to enlarge their plantations. More measured advocates said the corporations were still doing the right thing, but needed help. Then, in the middle of all this, members of the Indonesian government began saying that no-deforestation pledges must be rolled back so that small farmers could cut down forests to make a living.

A helicopter drops water to extinguish a fire at a plantation in Kubu Raya district, Indonesia. Reuters/Antara Photo Agency

What the heck is going on here? Through the fall and winter, I collected reports, and after spending the last week reading and reporting, I have a hypothesis. What we are seeing is the messy birth of a new era in Indonesia: a transition from a feudal economy to a more accountable and democratic capitalistic system. Here’s my educated guess about what has happened over the last few years.

1. Background: Between 1967 and 1998, Indonesia was a dictatorship under Suharto, who maintained control over the far-flung islands in par by giving natural resources to regional power brokers in return for political and military support. That exchange of land for allegiance is the essence of feudalism — it’s a contract between local leaders and members of the central government that excludes the people. Elements of that patronage system still linger. Of course, any system that doles out land as yet-to-be-extracted wealth is terrible for the environment.

2. In the late 1990s, activists raise a hue and cry over the loss of Southeast Asian forests. Large corporations operating in Indonesia realize they are accountable to customers all around the world, not just the government. They begin hiring sustainability teams, and by the mid 2010s they pledge to stop buying products that cause deforestation.

3. But these corporations are so big that they have no clue where their raw materials come from. Business as usual continues on the ground. Meanwhile, 2015’s strong El Niño system dries everything out, making it easy to clear land with fire.

4. As the corporations trace their supply chains back to the source, they bump into companies actively clearing land and tell them to turn off their tractors. For the most part, this works. But they also bump into entrenched interests with no desire to reach zero-deforestation. For instance, when the big corporations told a company called Mopoli Raya that they would stop doing business if it continued to clear forest, Mopoli Raya essentially flipped them the bird. Those bigger corporations actually made good on their threats and canceled their contracts.

5. As old-guard power brokers and companies like Mopoli Raya begin to feel the no-deforestation commitments biting into their wealth, they run to the government to ask for help.

6. Indonesian government ministers in charge of agriculture and timber announce that the goal of “no-deforestation” is too ambitious. But the president, along with the trade and finance ministers, supports the corporate commitments. Insiders watch to see what the weather — both political and physical — will bring this year.

As I said, this is my hypothesis. There are two points in particular that are controversial and worth a closer look. First, I think evidence suggests that the big companies are honoring their commitments, but some people claim that the no-deforestation commitments are worthless and the big corporations are still encouraging land clearance. Second, the data I’ve seen leads me to think that small farmers are setting fires and clearing land at the behest of rogue companies and political bosses that have maintained Suharto-era land-for-power trades, but some people say that the poor need deforestation for economic development.

Are the companies that signed no-deforestation pledges setting fires?

There’s a natural inclination to blame the big multinational corporations. After all, those were the groups environmentalists targeted in the first rounds of the campaigns. Now, some environmental groups have shifted to focus directly on the smaller companies that are actually clearing forests, while others continue to pound the same big corporations that have pledged to end deforestation.

In December 2015, Friends of the Earth released a report called “Up in Smoke,” which accused Wilmar and another palm oil company of following a cynical strategy: “Burn, degrade, develop, legalize.” Friends of the Earth used satellite photography to show that fires had burned down forests within forest concessions held by these companies. When they sent people to check on some of these sites, they brought back pictures of oil palms growing amid the ashes. Taken alone, this seems damning. But as I read the responses from the companies and learned about the larger context, the report makes less and less sense.

In its response, Wilmar explained that it would not profit from the burned area. The company has committed to restoring original “high carbon value” forest that burns. Rather than making money off palm oil in those areas, they would be spending money for ecological restoration.

And what about the places where someone had already planted oil palms? All the evidence suggests that local communities had done this burning and planting. Wilmar’s response reads: “Some fires were the direct result of activities by nearby local communities. Evidence of boundary pegs for land claims and rice cultivation were found in two of our concession areas. Among the local communities surveyed, numerous individuals were open about their use of fire as a traditional practice.” Furthermore, Wilmar doesn’t buy palm fruit from these areas, and has reported the clearances to the authorities.

But why would someone develop land within a company’s concession, if not to serve that company?

Scott Poynton, founder of the nonprofit The Forest Trust, which monitors the progress of companies, including Wilmar, explained that, out in the jungle, the concession borders mean very little. There’s lots of land and lots of contested claims. “There’s no ‘oh, that’s someone else’s land, best leave it alone’ niceness going on,” he said. It’s easy enough for a rogue company to help farmers set up a plantation within a concession area that a company like Wilmar wants to keep as wilderness.

A similar charge was leveled at the company Asia Pulp & Paper (or APP): Environmental groups found fires within the company’s forest concessions, sparking outrage and boycotts. “The irony, however, is arguably no Indonesian company is doing more to atone for past sins than APP,” wrote Rhett Butler, a respected journalist and founder of the environmental news site Mongabay. An evaluation of APP by the environmental group Rainforest Alliance found that the company had managed to stop deforestation by its suppliers, and that ongoing forest clearance was the work of “third parties (not supplier companies), whether due to illegal logging, encroachment or issues of overlapping tenure.”

Are small farmers to blame?

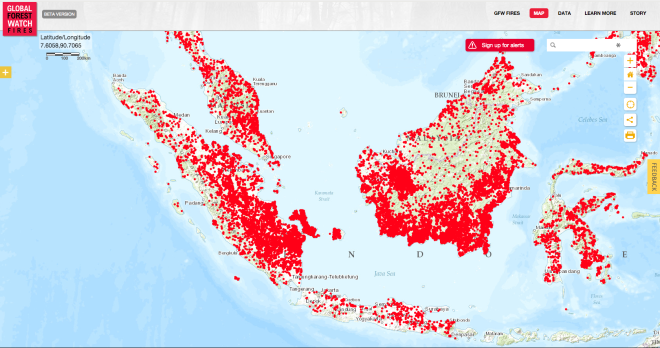

Fires in 2015Global Forest Watch

It’s easy enough to point to fires within corporate land concessions. But zoom out and it’s clear: There were fires everywhere in Indonesia last year — or at least wherever there are farmers. Remote areas suffered fewer fires, which was good news for the intact primary forests. It seems likely that farmers were the cause — or at least the proximate cause — of most of the fires. When researchers have looked closely at representative burned areas, they found that four out of five fires started outside the big plantations, and even within company concession areas, were on land managed by small farmers.

In a conversation between Scott Poynton and Jesslyne Widjaja, head of sustainability for the palm oil company Golden Agri Resources, Widjaja said that there’s no clear data on who is setting the fires. Some of the burning is done by rogue companies, she said, “but I think the majority of the burning is by the smallholders of the community, where they have known this practice for a long time, so it is a cultural thing.”

It’s not just the big companies saying this. In an interview last year, Rolf Skar of Greenpeace told me that organization found itself in an unaccustomed role: working alongside corporations to protect forests from rural communities.

So is this a classic case of poverty versus the environment? Is deforestation necessary to lift rural Indonesians out of poverty?

The Indonesian ministers of agriculture and forestry have argued that point, claiming that the no-deforestation pledges are hurting development. Deputy agriculture minister Musdhalifah Machmud told Reuters that the big corporations need to relax their commitments and start buying palm fruit from farmers who clear forests.

“Yah, they need to let smallholders fulfill their trade,” she told Reuters.

But after doing my reporting for this story, I don’t think this is a case where the environment must be sacrificed to enrich the poor. Analysts have shown that there’s plenty of degraded land to support a thriving palm-oil industry for Indonesia. It seems more likely that land-holding power brokers — like the owners of Mopoli Raya — put pressure on the government when they began to feel the no-deforestation pledges squeezing their pocketbooks.

“They ran to the government and demanded the protection they’ve always gotten in the past,” said Glenn Hurowitz, a senior fellow at the Center for International Policy. It just sounds better to say that no-deforestation pledges are hurting poor farmers rather than saying that those pledges are hurting the intimidating characters who gained power in the days of military dictatorship.

The small farmers themselves aren’t clamoring for more land clearance. Mansuetus Darto, leader of the Oil Palm Smallholders Association, told Mongabay that farmers support the corporations making no-deforestation pledges, because those companies are helping them improve yields. Small farmers don’t need more land to improve their lives, he said — they simply need to make more money, and they can best do that by growing more on the land they already have. Small farmers can triple or quadruple their yields if they have access to basic training and agricultural technology, like fertilizer. And the corporations that have made deforestation pledges are working with small farmers to provide the training and technology they want.

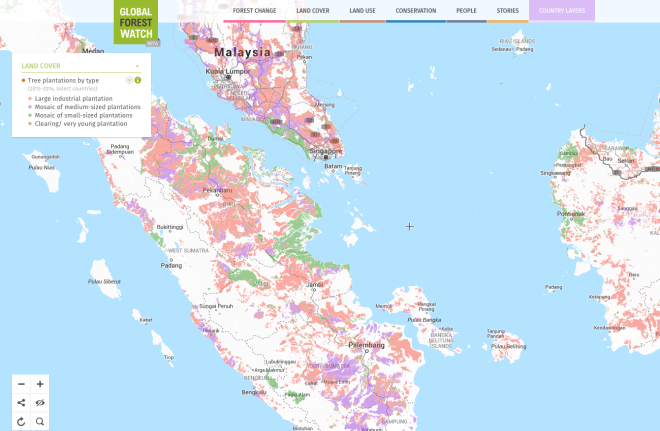

Large plantations (red) along with small (green), and medium sized farms (purple).Global Forest Watch

Darto told Mongabay that government officials don’t want to stop deforestation “because they don’t want to lose the power they have with licensing.” That is, as long as there’s agricultural expansion, then government officials can gain power by doling out concessions to their cronies.

One way or another, small farmers are going to grow more wood and palm fruit so they can raise their standard of living. That’s either going to happen by expansion or increasing yields. There are shady companies who would have farmers expand on the cheap, by clearing forest. On the other side there are the bigger, established companies, investing in programs to modernize production and help small farmers improve their yields.

So are small farmers to blame? The evidence suggests that they were the ones striking the matches, but they didn’t do it on their own. Farmers wouldn’t be developing more land for oil palm and pulp wood if there weren’t powerful people promising to buy those products.

What happens next?

Today palm oil (and pulpwood) production is still driving massive deforestation. Hurowitz told me he thinks the big companies can do more to end the land clearance, but they will need the help of government regulation and enforcement. At this point, many within the Indonesian government want to end deforestation, but there’s also a lot of resistance: The government still hasn’t taken the basic step of releasing the landholdings maps showing who owns what. Without that basic level of transparency, it’s impossible to really tell who is responsible for the fires, and accountability is just a pipe dream.

It seems to me that shift to modern democratic capitalism is well under way among the large corporations like Wilmar, APP, and Golden Agri Resources. They have seen that, in the long run, they need to be sustainable. That doesn’t mean they are sustainable yet, but they are pushing their reforms down the supply chain — this year Wilmar is working to trace its palm oil down to the plantation level. That’s not nearly fast enough for some environmental organizations — particularly the ones ideologically opposed to globalization and capitalism. Nevertheless, progress has been fast enough to send Indonesia’s old guard into conniptions.

It looks to me like Indonesia is at an economic crossroads. If it freezes its agricultural footprint and focuses on increasing yields, the feudal political patronage system will fall apart. The government, instead of being accountable to regional power brokers, would become more accountable to the people, and more able to institute real reform. And the corporations would become more accountable to the international marketplace.

Indonesia seems very far away — before I started writing about palm oil, I definitely couldn’t point it out on a map — but if Americans started taking an interest in this story, we could help. At the government level, the U.S. could help in several ways. At the individual level, people can work with the advocacy organizations (Forest Heroes, The Nature Conservancy, World Wildlife Fund, The Rainforest Alliance, The Forest Trust, World Resources Institute, and many others) which have done a terrific job of showing corporations that consumers are not going to support unsustainable companies.

Last year was especially dry, terrible for Indonesian forests. But before that, forest loss seemed to be slowing. With enough of a push, things could get back on track.

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly stated that Wilmar aimed to trace all palm oil back to the plantation level this year. The error came from a misreading of this document, which says that Wilmar is working on traceability back to plantations this year, but does not set a target for the completion of that work. To make amends, the writer will face palm.