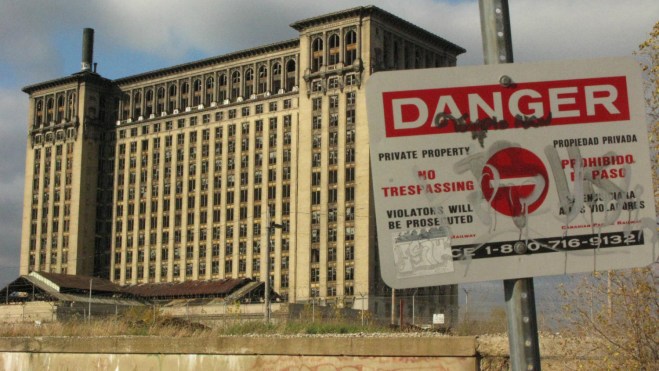

There are few sights as eerie as an abandoned high-rise. Walk around the neighborhoods adjacent to Detroit’s Downtown — areas like Midtown and Corktown, the heart of the city’s sliver of much-heralded reinvestment — and you can see buildings rising some 20 stories that sit empty. Windows are blocked over with plywood, or sometimes you can see right through them, where the glass used to be. Detroit is filled with vacant houses too. But the occasional empty house is not unheard of in any city. Abandoned high-rises are abnormal, and chilling. Neighborhoods surrounding them feel worse than merely distressed — more like post-apocalyptic.

Detroit’s population peaked in the 1950 census at 1.85 million, making it at the time the fourth-largest city in the U.S. It’s been straight downhill since then. In 2010, Detroit had just under 714,000 people, ranking 18th largest in the country. While other once-mighty old industrial cities — Buffalo, St. Louis, Cleveland, Baltimore — also lost most of their population in the second half of the 20th century, they have since begun to stabilize. Detroit just keeps circling the drain. It lost almost one-third of its population between 2000 and 2010. Although we won’t know precisely until the next census, Detroit appears to have kept losing people since then; the Census Bureau estimates that the population dropped below 700,000 in 2013.

As Detroit has lost population, it’s lost density too. Detroit and many other “legacy cities” such as St. Louis and Cleveland now have densities — about 5,100 people per square mile — similar to newer, Western suburban-style cities like San Jose, Calif., and far less than L.A., which has about 8,100 people per square mile. (New York City, by comparison, has 27,000 people per square mile.) Cleveland now has just 43 percent of its peak population, and St. Louis and Detroit have only 37 percent. They have much of the infrastructure to support significantly larger populations — they could sustain densities more like Washington, D.C., at around 10,000 people per square mile, or Chicago, which has almost 12,000.

Density is directly correlated with carbon emissions. Denser cities have lower emissions from transportation because residents drive less and drive shorter distances. And cities in general have lower emissions than suburbs for the same reasons. It’s economically and ecologically wasteful to build out new roads and sewers to serve new homes in new suburbs when you could instead move people back into legacy cities, and lower their carbon footprints in the process.

So it would be good for the environment if people could be cajoled into moving to places like Detroit — but can they?

On first glance, the view from the Rust Belt is not promising. Factory jobs have fled south to cheaper locales, or out of the country altogether. Newer businesses are locating in more fashionable cities, or in warmer areas with plentiful land, from Florida to Arizona. Retirees who can live where they want are also choosing balmier climes.

If you read national newspapers and magazines, you might get the false impression that Detroit, Cleveland, Buffalo, and other such cities are in the midst of a boom. All it takes to trigger a cascade of stories about urban renaissance is a handful of yuppies moving into a gritty urban neighborhood and one cute coffee shop opening up. And that kind of gentrification is happening in a few pockets of each city, but it’s swamped by continued decline.

If you were to look at maps of these legacy cities tracking changes over the last 10 or 15 years, what you would see is a tiny area in and around each city’s downtown that has experienced an increase in median incomes and home prices and often an increase in total residents. But surrounding that, covering a much larger area, would be continuing decline. Median incomes, home values, and population densities are stagnant or dropping. Middle- and working-class white residents are still fleeing and they are increasingly joined by middle-class African-Americans. If the population is stable or slightly growing, that’s mainly because of some foreign in-migration, usually from Latin America. You have to travel further out to the suburbs — or perhaps to a quasi-suburban neighborhood at the far edge of the city — to find home values and incomes holding steadier.

While you can see this pattern at work in many older cities, it’s more extreme in some than others. Legacy cities like Philadelphia have received an influx of young professionals and their gentrifying areas therefore stretch a bit farther into neighborhoods beyond the downtown. Then you’ve got cities like Baltimore, with fewer millennial migrants but still some notable regeneration. At the very bottom, with an influx barely large enough to register statistically — even though it’s quite noticeable in a few neighborhoods — is Detroit.

One employee of the Detroit Land Bank suggested to me that the incredibly low price of housing would attract young people from all over the country. “Ten years ago everyone wanted to move to Brooklyn,” she said. “And now it’s Detroit.” The data doesn’t support that. Detroit has experienced a tiny increase in college-educated millennials, but it’s a drop in the massive, empty bucket.

It’s hard to imagine why anyone with a choice would opt to live in Detroit over other cities. The winter is cold — the average January temperature is 24.5 degrees. Crime is high, and city services like emergency response and snow plowing are not delivered in a timely manner, if at all. Property taxes are enormous. This keeps Detroit stuck in a downward spiral: it lacks the residents and therefore tax revenue to deliver city services to its sprawling population; it keeps tax rates high to get the most money it can out of the few residents it has (though many residents simply don’t pay up); and it’s hard to attract new residents because of those high taxes and poor services.

Detroit does have one particularly appealing attribute: its architecture. The downtown office buildings include some of North America’s finest. Its housing stock is filled with handsome, old detached Tudors and even some Italianate and Romanesque Revival mansions. “There are areas around northeast and northwest Detroit that could be stabilized and show some modest growth, like Rosedale Park and East English Village,” says Allan Mallach, a senior fellow at the Center for Community Progress in Washington, D.C., and author of numerous reports on older cities. “What you’ve got there are areas that simply have gorgeous houses at affordable prices.”

The opportunity to live in an attractive older home for a low price has enticed creatives and professionals to impoverished and crime-stricken neighborhoods from Brooklyn and Boston to San Francisco. So why not Detroit? Unfortunately, it is losing that very asset as many of those buildings are abandoned and have to be razed to avoid turning into magnets for crime or fire hazards. There are plenty left — a surplus, in fact, that keeps their prices remarkably low — but until every brick rowhouse in Philly and Baltimore has been become expensive, Detroit isn’t the best option for the typical penurious-but-hip young artist because the quality of life is so precarious. “If you can create an environment where people feel reasonably safe and that their property taxes are not insane relative to what the house is worth, I think you will see people moving back into those neighborhoods because the houses are gorgeous,” says Mallach. But those are big ifs.

Detroit has other virtues too, but even some of those are just positive side effects of overall negative trends. The shrinking population means negligible traffic, ample parking, and comfortable biking.

The Detroit Riverwalk.Michigan Municipal League

But auto theft is a massive problem. When I asked Mike Score of Hantz Farms, a tree farm on vacant lots in Detroit’s Lower Eastside, whether we should take his car or mine for a 30-minute trip from one lot to the next, he said we’d take both so as not to leave a car unattended. It was 3:00 p.m. The result of all this crime is that auto insurance rates are the highest in the nation, up to $5,000 per year. They’re so high that an estimated 60 percent of Detroit drivers don’t have auto insurance, which means they have to flee the scene if they hit someone.

Given all this, why would anyone choose Detroit over, say, Portland, which has better weather, more beautiful surroundings, and much lower crime? It’s not as cheap as Detroit, but it has much lower rents than other temperate, outdoorsy cities like Seattle and San Francisco. (Interestingly, Portland — despite its reputation for smart urban planning — is slightly less dense than Detroit, which reflects the inherent higher density of older cities.) If Portland is too twee or expensive for you and you don’t mind Midwestern winters, Minneapolis and Milwaukee are healthier than Detroit but affordable compared to coastal cities. The millennial priced out of Brooklyn, or even Queens or Jersey City, could move to the Bronx or Newark and still be a short train ride from Manhattan and Brooklyn. What holds the Bronx or Newark back from gentrification is their poverty, blight, and crime. But all those problems are worse in Detroit, and in smaller Midwestern basket cases like Flint, Mich., and Youngstown, Ohio. And if you really want to live in a troubled-but-cheap city, why choose Detroit over Baltimore, which has a stronger urban fabric of affordable rowhouses, milder winters, and is less than an hour by train from Washington, D.C.?

Also, people cannot just live where they want. They need jobs. This is why Baltimore benefits from being within commuting distance of D.C. You can buy a beautiful house in Detroit for $60,000, but then how are you going to earn a living?

Recently a New York Times op-ed, noting that foreign immigration has kept many major American cities healthy through lean years, argued for letting Syrian refugees into the U.S. on the condition that they settle in Detroit. But immigrants, just like the rest of us, follow jobs. What would Syrian refugees do for a living in Detroit? (It’s also worth noting that there’s a large Middle Eastern community in the Detroit suburbs of Dearborn and Dearborn Heights. Upwardly mobile immigrants make the same calculations about crime and schools as upwardly mobile native-born Americans.)

Most of the millennials in Detroit are simply young people who work in the region and are opting for the city over the suburbs — and more of them could be lured in. There are in fact many white-collar jobs in Detroit and other big Rust Belt cities. A car company may move its factories to Mexico, but not its headquarters. And then there are “eds and meds,” the major institutions like universities and hospitals that are firmly entrenched in older cities. If they can spin off startups in industries like biotechnology, they can even anchor a post-industrial economic revival, as has happened in Pittsburgh.

“Downtowns of legacy cities still have plenty of employment,” notes Mallach. In Detroit there are more jobs (232,000) than employed Detroit residents (169,000). The problem is that most people working in the city live in the suburbs, while most employed city residents reverse-commute to the suburbs. Well-paying white-collar jobs in downtown office buildings are held by suburbanites, while blue-collar or service jobs — cleaning those corporate executives’ homes, for example — are in suburbs but often held by poor Detroiters who can’t afford to live there. For Detroiters who also can’t afford a car, the result is an obscenely long and difficult commute.

So what Detroit and cities like it must do is not so much attract people who would otherwise be Brooklynites but attract people who would otherwise be suburbanites. On that front, Detroit has some reason to be hopeful: Young people are more likely than their parents’ generation to want an urban lifestyle. The popularity of walkable urbanism is on the rise, and millennials are less fond of driving than older people are. That’s why the neighborhoods in Detroit that are attracting young professionals are not the ones with the best housing stock, but the ones nearest to Downtown. They offer more walkability, shorter commutes, and access to what little mass transit Detroit has to offer. Density is not just a product of desirability, it also creates it.

Ironically, the legacy of Detroit’s car-oriented sprawl is such that there is actually an undersupply of housing, and especially apartments suited for childless people, in these more desirable, walkable areas. “A lot of millennials who may move to Detroit may not want to live in a single family house,” observes Eric Dueweke, an urban planning professor at the University of Michigan and lifelong Detroiter. “Detroit boomed with the invention of the automobile, so people had cars starting in the 1920s,” says Dueweke. “So what did they do? We had some of the first freeways, some of the first shopping malls.” The solution, according to Dueweke, is to build on the greater density in the core around Downtown with new apartments, and eventually that demand may spread outwards.

This is the pattern that high-demand cities have followed. Two decades ago, no one would ever have predicted that Bushwick, Brooklyn, would become a hotspot for hipsters. It was poor, dangerous, and blighted with ugly or empty old industrial buildings, and seven stops from Manhattan by subway. But Manhattan’s East Village spilled over to Williamsburg in Brooklyn, and in due course to Bushwick.

Detroit appreciates this, which is why it is building a light rail line along Woodward Avenue from Downtown to Midtown. The just-released Detroit Future City master plan, rather than seeking to repopulate the city evenly, calls for turning abandoned stretches into a greenbelt surrounded by pockets of denser, mixed-use urbanism.

Another problem for Rust Belt cities is that most young professionals still move to the suburbs when they have children. The same home that costs $50,000 in an outlying but relatively stable neighborhood in Detroit might cost $250,000 in a middle-class inner-ring suburb. That’s a big price difference, but a couple making a combined $100,000 per year can easily qualify for a $200,000 mortgage. In exchange for the extra $200,000, they get better public schools, lower crime, and a police force that responds if they call 911. They also won’t be living near abandoned homes and empty lots.

And that’s Detroit’s other challenge: If density is its advantage compared to the suburbs, then its massive population loss reduced that very strength. Like most other legacy cities, it unwisely took out its trolley tracks and retrofitted itself to accommodate cars. Now that mass transit is back in fashion, it lacks the density outside of a few corridors to rebuild it. It has buses, but beyond Downtown they appear to be few and far between. If a bus serves an area now bereft of residents, then it won’t make sense for it to keep a frequent schedule. The main thing legacy cities need to attract residents, in other words, is residents — a catch-22 if ever there was one.

So what if Detroit can’t gain back its lost population? There are other ways for it to grow greener. Abandoned lots can be turned into farms where Detroiters grow their own food, cutting down on the emissions of shipping everything in. That’s already happening in parts of the city.

“I’m less hopeful about large numbers of people moving to Detroit than I am about us becoming a much greener place by using our land in better ways,” says Dueweke. But that, in turn, may one day help increase demand. Being green, after all, is also an attraction for millennials. Just ask Portland.