Matthew Mazzotta was in Vermont, visiting his friend Guy Roberts. At some point, as you do, he and the friend got onto the subject of what the hell his friend was doing in Vermont.

“I’m working on a scalable methane digester with parts that clip together and scale up depending on how many cows you have,” said Guy. “It makes free energy.”

“That’s impossible,” said Mazzotta.

“No it’s not,” said Guy. “The little microbes in the manure breathe out methane. It’s naturally occurring.”

Both parts of this conversation are being acted out for me by Mazzotta, while we both sit at the studio he’s working out of during a residency at the Headlands Center for the Arts in Marin County, Calif. It was a moment that set Mazzotta on a fateful course.

“It wasn’t until further down the road that I realized that it had this environmental element to it — that if you burn methane it separates from the carbon dioxide and turns into water,” he said. “So basically it came down to free energy and it was good for the environment. I was shocked. It could not be so.”

Here’s how I first heard of Mazzotta: In 2010, I was working as a city reporter in San Francisco. My editor assigned me to write a few stories about poop in the city. It didn’t so much matter what I wrote about it, as long as I wrote something. It was, she was convinced, reliable traffic bait — like murder, or parking.

Here’s how I first heard of Mazzotta: In 2010, I was working as a city reporter in San Francisco. My editor assigned me to write a few stories about poop in the city. It didn’t so much matter what I wrote about it, as long as I wrote something. It was, she was convinced, reliable traffic bait — like murder, or parking.

So I began looking into this poop and the city beat. I researched people pooping on the sidewalk. (Only illegal since 2002!) I interviewed an idealistic maker of public composting toilets. And I found a great poop mystery: a plan, circa 2006, to collect dog waste at city parks and convert it into energy, that first was much-hyped, and then vanished.

The concept raised an important question: For centuries, cities have dealt with poop by asking “How do we get this waste safely AWAY from our city as far and as quickly as possible?” While the underpinnings of this idea have been called into question in this age of sustainability and energy awareness, there’s been precious little actual experience on the ground with alternatives.

This was a project that seemed tailor-made to assuage the collective guilt of San Francisco — a city notorious for having more dogs than children, a city where 3.8 percent of residential trash collection falls under the category of “animal waste,” and a city that likes to do weird things and then brag about them later. Also: a city with a goal of producing zero waste by 2020.

But it never happened. Nada. It was never formally canceled. It just faded until it was gone, like so many California dreams.

Then I heard something else: The same project had been attempted on the East Coast, in Cambridge, Mass., and there, it actually happened. The secret? Mazzotta pitched it, not as an environmental improvement, or an expression of civic virtue, but as an art project. Maybe art could be the secret weapon that got America over its poop fears.

Matthew Mazzotta

At the time, Mazzotta was making art that encouraged people to hang out with each other in public spaces. He collaborated on a bicycle-powered bus project whose final form was part centipede, part longboat. He disguised a binocular-enabled people-watching station as a utility box, and built and hid an entire folding teahouse inside a loading dock (not well enough — the teahouse was eventually stolen).

Matthew Mazzotta

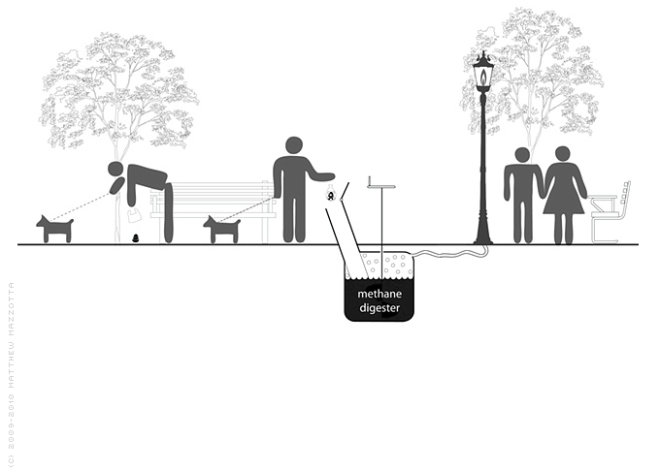

One day in 2009, walking down the street in Cambridge, where he was finishing a graduate degree in art at MIT, he passed a dog park surrounded by trash cans heaped with poop bags. He’d just been in India on a research trip; in the houses he’d seen there, residents cooked on burners powered by the methane generated by cow dung. So at that moment, to him, the trash cans weren’t just trash cans — they were a waste of something that could be incredibly useful.

Mazzotta did some research, found an article about San Francisco’s dog-waste power plan, and got in touch with Will Brinton, an environmental scientist who had consulted on the project. Brinton told him why the project had never been built: too much red tape. Who was going to maintain it? If it produced energy, did it need to be classified as a business? “The idea is there,” Brinton told Mazzota. “But no one can do it.” Also, there was no glory in it, science-wise — no possibility for publication or greater renown. The technology was too simple.

“I want to do it as an art project,” Mazzotta said.

“That might just work,” said Brinton.

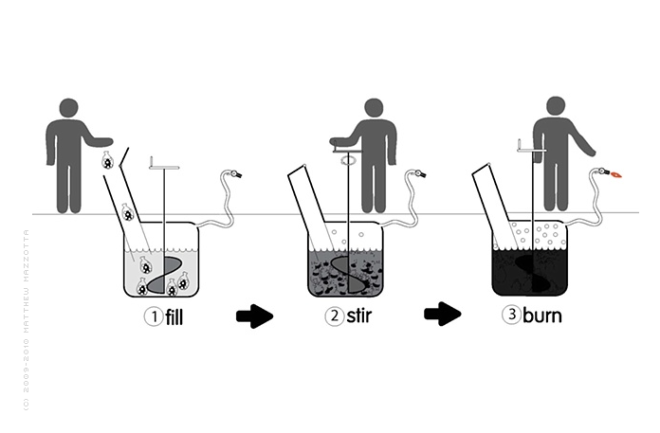

The two met up in Maine and began working on a prototype — a simple metal drum with a lamp attached via a gas valve. They filled it with manure from a nearby cow pasture and left it overnight for the methane to build up.

When Mazzotta came back the next morning, the gas pressure had busted the drum open. They glued the contraption back together. The next time he went out to light the lamp, it worked. “I’m showing it to everybody,” Mazzotta recalls thinking. “You see that light in the field? That’s cow shit!”

Mazzotta went to Cambridge Park & Recreation to talk permits. Nice idea, said Park & Rec. But no way. Playing with methane was the kind of thing people should do on the farm — not in the big city. Mazzotta explained that the whole point was to build a methane digester in the city, where there were dogs. Maybe, said Park & Rec.

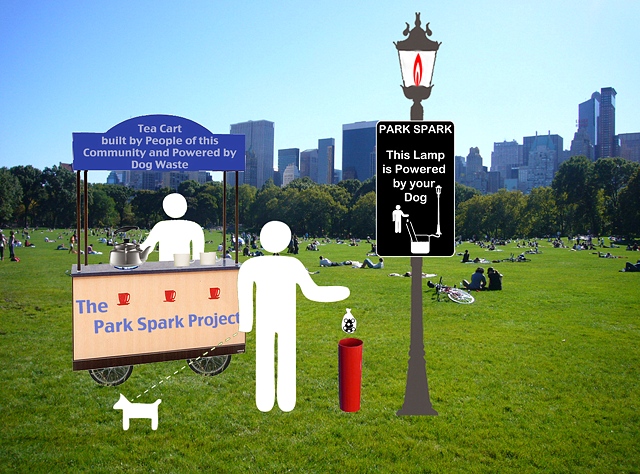

Park & Rec wasn’t the only agency that needed to be won over. There was the EPA. The fire department. The Open Space Committee. Building permits. A month went by. Then another month. Then seven months. He gave the project a cute name (“Park Spark,” after the lamppost). He was going from agency to agency and department to department, making his pitch, learning to speak the language of the engineer to the engineers, and the language of the city planner to the city planners, and bringing in Brinton to talk science when he needed a scientist.

Mazzotta began to feel like something, and he realized what it was: He was acting like a businessman.

Matthew Mazzotta

A decade earlier, this would have been inconceivable to him. In the ’90s, as part of an Atlanta-based veganer-than-thou hardcore scene, Mazzotta’s encounters with authority came mostly in the form of protests over the most protest-y injustices of the ’90s: Animal rights. The environment. Zapatistas. “I yelled and yelled and yelled,” he recalls. “A lot of that was about the environment. But it was also about why weren’t things more beautiful.”

Many things about being in the hardcore punk scene were great, especially the music. But as Mazzotta grew out of his undergraduate years, certain cultural practices that came with the scene began to wear on him: “All we were talking about was being vegan and being straightedge. Did you buy leather shoes? If you buy leather shoes at a thrift store, is that OK because they’re used, or bad because you’re endorsing the wearing of leather? So you eat tofu. The guy who is driving the tofu to you, what did he eat for lunch? Did the truck kill any insects on its way to deliver the tofu to you? At the end of the day, nothing is vegan. Because to get it to you, people had to do all of this crazy shit that is killing the environment.”

In 1999, Mazzotta got accepted into the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. At that point, he had everything that a person in the hardcore scene needed to be fulfilled — namely, friends and a van. But as he prepared to move, he had a realization: “I am going to where people don’t know me. I am going to see why people do other things. I just want to see more.”

And now here he was, meeting with city functionaries about dog park art, talking about minutiae. Would the digester smell? (Because it was burning off methane, it would actually reduce dog park odor.) Would the bags used to pick up dog shit clog up the inside of the container? (Only if they weren’t compostable which, admittedly, most of them weren’t. Using newspaper would work — but since picking up poop with newspaper was a lost art, Mazzotta had negotiated a supply of legit compostable bags for the park itself.) Would it blow up? (With a spark arrestor, it was about as likely to explode as your car.) And what to do with the energy? Mazzotta had big dreams — he could power a public tea-kettle, or a communal popcorn popper. Everything was vetoed.

So Mazzotta went to the Netherlands. He built a digester there, in a cow pasture, and built a teahouse and had it covered in the same reeds used to roof local houses. The goal was to make it look like a part of the landscape, but more than a few people thought it made it look like a giant coconut.

Everything worked. Nothing exploded. Mazzotta returned to the U.S. with pictures of happy Dutch people foraging for tea ingredients by the side of the road and drinking their manure-heated tea, and he showed them to the last few Cambridge holdouts. See? See these happy Dutch people? He got the last permit he needed. He could only do it as a temporary project — but he could do it.

He began building the installation at MIT, trying to design its two tanks for every terrible thing that someone might try to do to them. He found an old crank at an antique shop and attached it to the outside, in the hopes of enticing visitors to stir up the contents of the digester and keep it aerated. A friend designed simple decals to explain the process. They pre-loaded the tanks with cow manure donated by a farm outside of town, left it sealed for a while, and then went to light the lamp. Nothing.

Mazzotta panicked and ran over to Harvard, looking for help. Your digester is pickled, a researcher from Harvard explained. Too acidic. Add some baking soda. He went back and did that. The lamppost lit up. Victory.

The next day, he got a phone call. “This is Kyle,” said a voice on the other line. “From the BBC.” Then CNN called. And Wired. Mazzotta did about 75 interviews in about two weeks. Friends began to get in touch with him from around the world, saying they’d seen him on television in the strangest contexts.

He got invited onto conservative talk radio. There, when he began talking about methane and climate change, the host stopped him. “You know that climate change is a hoax,” the host said. Mazzotta paused. “They want me to fight,” he thought. “I’m not going to fight about this. I’m beyond that.” The whole point of the project was to get people who would never think about climate change to think about waste and nature.

No one threw anything crazy into the digester. People loved turning the crank outside the tank so much that when Mazzotta showed up occasionally to check in on the project, there was no need to even stir it. News crews would show up and film people walking their dogs and tossing poop into the tank. While city waste haulers refused to even touch the tank, Mazzotta found a company that handled zoo waste to periodically stop by and prevent any overflow.

When the time came to take out the digester, he says, the city had second thoughts — maybe it should be permanent. But it was too late. Mazzotta was moving to Korea; he’d only built it as a temporary installation, per their request. He was done with the project.

Mazzotta posted as much information about Park Spark as he could online, so that anyone else could build their own. Five years later, he still gets an email a week about it, but as of yet, he doesn’t know of anyone who has made their own version. Instead, people tend to pick up his plans, use them to pull down grants for local community improvements or art projects, run through the money, and then never do anything.

Who are these people? Song-and-dance men, using a once-viral idea to get a quick buck? Idealists who just can’t figure out how to get through seven months of city meetings? Maybe Mazotta’s time in the hardcore scene left him uniquely equipped, as an artist, to endure that kind of scrutiny. Maybe it’s just too excruciating for anyone else.

“I’m glad I got out of this thing,” Mazzotta said. If he’d stayed, as he put it, “with the tanks and the insurances,” he wouldn’t have time to do anything else.

For example: He never did the analysis on whether or not Park Spark actually saved any energy. After all the energy that went into making the tank, and the steel that went into the tank, how long would it take for Park Spark to produce as much energy as had gone into it?

The good thing about an art project was that every time someone asked you what you were doing, you could just say “art.” You didn’t have to think about performance metrics.

After Park Spark, Mazzotta’s art became very context-specific. Park Spark could have been installed anywhere with a dog park. The new projects are more wrapped up in the story of the place where they’re built. He turned an abandoned house in York, Ala., into an auditorium. It could be considered an environmental project (reclaimed wood, etc.), but he found that he had more interesting conversations with people when he didn’t describe it that way.

[protected-iframe id=”da18d5e028b6a53728eea2053cd25e2d-5104299-30178935″ info=”https://player.vimeo.com/video/70386286″ width=”660″ height=”330″ frameborder=”0″ webkitallowfullscreen=”” mozallowfullscreen=”” allowfullscreen=””]

The history of cities and shit (and I’m talking about literal shit here, that thing we all excrete and then have to figure out how to get rid of) is an amazing one. For example: In 1933, a “night soil war” erupted in Beijing when the city’s new mayor tried to break up the monopoly that emptied and sold the contents of the city’s public toilets. During the Cultural Revolution, peasants from the countryside would come into the city to raid public toilets to use as fertilizer.

Before the arrival of chemical fertilizer and cheap energy, shit was … well … useful. Historians believe that the Assyrians used the methane that offgasses from it to heat their bathwater. In 1895, streetlights in Exeter, England, ran off of the same thing generated by a local sewage treatment plant.

So Mazzotta’s project wasn’t that far out there, even by the standards of today. Today, biogas operations are found out in the countryside — particularly out in the countryside in other countries. San Francisco may never have actualized its pet dropping dreams, but Sunset Scavenger, the city’s waste hauling company, won a prize for capturing the gas coming off of yard trimmings and food waste and using it to power its dump trucks (with the equivalent of about 120,000 gallons of diesel fuel). A project like this is way more ambitious — and way more efficient — than the long-forgotten dog park plan. The dogs of San Francisco would have to work pretty hard to compete with all the squishy old apples, rotten chard, and expired yogurt that its residents generate.

Still, the beauty of a project like Park Spark was that it bestowed a sense that by using it, you were doing something virtuous, and at very little cost to yourself. It may feel like a jerk move, environmentally, to throw your dog’s poop in a trash bin, but I doubt many San Franciscans are following the advice that I got, so many years ago, from a Recology spokesperson: Just bring dog poop inside and flush it down the toilet. (Please join me in being amazed that there is a special outdoors toilet available on the market for this very purpose.)

But let’s stop being practical for a moment, because this is a story about an art project, after all. Let’s get futuristic. In the same way that streetcars and bicycles and city chickens are making a comeback, could city poop do the same? Is there a plausible future where I would come back to my apartment to find glossy mailers from energy startups, stuffed in between all the flyers from Washio and Munchery, looking to lock up the rights to the contents of my building’s toilets?

Mazzotta’s project proved one thing: A city biogas project can be wildly popular. But it also proved something else: The real future belongs not to those with the best ideas, or those with the most money, but to those who can sit through seven months of meetings and not falter. Let’s remember that, as we boldly go into whatever future we are fighting for.