Thousands of cargo ships cross the oceans every single day, carrying everything from cars and clothing to plastic pellets and garden gnomes while their giant engines pump greenhouse gases into the air. The shipping industry plays a starring role in global trade, and as its emissions continue to swell, regulators are starting to consider an ambitious yet contentious idea: making shipping companies pay for their pollution.

The International Maritime Organization agreed at its meeting in June to discuss proposals to put a price on ships’ emissions at the IMO’s next meeting in October. In the slow-moving, bureaucratic realm of shipping, even this subtle move was seen as a big step. The last time the United Nations agency formally debated “market-based measures” was eight years ago, and the effort was ultimately abandoned amid widespread disagreements.

Since then, the industry’s annual emissions have risen by nearly 10 percent, according to the IMO’s latest research, contributing nearly 3 percent of the global total. If ships keep burning oil instead of switching to zero-carbon alternatives, those numbers are expected to soar in coming years as more vessels ply more routes, undermining the larger global fight to rein in greenhouse gases.

Experts say existing policies to curb fuel consumption and improve energy efficiency haven’t done enough to steer the industry toward a cleaner course. Much stronger measures are needed not only to slash emissions from existing ships but also to ensure new vessels are designed to operate in a decarbonized world. “It’s just becoming more and more urgent” for the IMO to act, said Aoife O’Leary, the London-based director of international climate for the Environmental Defense Fund. At past IMO meetings, activist groups like Ocean Rebellion have found their own way of pressuring regulators: spilling fake oil outside the London headquarters.

Making polluters pay

The main proposal on the IMO’s October agenda comes from the Marshall Islands and Solomon Islands — two countries especially vulnerable to rising sea levels and severe drought brought on by climate change.

The Pacific island nations have proposed requiring shipping companies to pay $100 for every metric ton of carbon dioxide equivalent they emit, starting in 2025. The price would then ratchet up every five years, making it increasingly expensive to use dirty diesel fuels and cheaper to use cleaner options, such as ammonia, hydrogen fuel cells, next-generation sails, and shoreside charging infrastructure where ships can plug in.

The concept already exists for other businesses. Around the world, nearly 60 national and local carbon pricing schemes encompass power plants, oil refineries, and steel mills. In Norway, ships pay a tax on emissions of nitrogen oxides, a harmful air pollutant. The funds are used to invest in pollution-reducing measures like building battery-powered ferries.

The proposal would use the money raised to help countries most vulnerable to climate change adapt and decarbonize. It would also help shipping companies shift from dirty fossil fuels and develop and deploy emerging (and expensive) alternatives.

“This gives renewable technologies the chance to compete with well-established, high-polluting fossil fuels that threaten our islands,” Albon Ishoda, the Marshall Islands ambassador to the IMO, recently wrote about the proposal.

The Marshall Islands has spearheaded the charge for climate action within the IMO. The country is home to the world’s third-largest ship registry and depends on cargo ships to import food, medicine, and other essentials. Yet Ishoda and others have warned that unchecked emissions pose an “existential threat” to the low-lying archipelago of 79,000 people. In 2018, the Marshall Islands played a key role in establishing the IMO’s first targets for cutting greenhouse gases. Now it’s pushing to ensure ships actually meet those goals.

A full-throttle shift

The IMO’s climate strategy calls for reducing the carbon intensity of international shipping by at least 40 percent by 2030, compared to 2008 levels. (Carbon intensity is a measure of a ship’s CO2 emissions, linked to the amount of cargo carried over a voyage.) The U.N. agency also wants to cut the industry’s total annual emissions in half by 2050.

At a June meeting held over videoconference, IMO members adopted short-term measures that require existing ships to meet energy-efficiency standards, as well as improve their carbon intensity by 2 percent every year between 2023 and 2026. Environmental groups and other critics said the policies fell well short of what’s needed to meet the organization’s own ambitions — let alone limit warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius over pre-industrial times.

“What has been done up until now is like business-as-usual,” said Michael Prehn, who represents the Solomon Islands in IMO negotiations. “So somebody has to make a proposal that will actually do something.”

Industry analysts and even some prominent companies have backed pricing carbon emissions to accelerate investments, both in alternative fuels and the infrastructure required to produce, store, and distribute those fuels.

Trafigura, a global commodities trader, is pushing for a levy between $250 to $300 for every metric ton of carbon emitted — the amount researchers say is needed to overhaul the way ships operate. Maersk, the world’s largest container shipping line, has called for a $150 carbon tax. “Fossil fuels cannot keep being cheaper than green fuels,” said Søren Skou, Maersk’s CEO, in a LinkedIn post last month. An industry-led initiative aims for a $2 tax on every metric ton of marine fuel.

Such initiatives face strident opposition from other shipping companies and countries that rely on exports. Argentina, Brazil, and Saudi Arabia have warned that stronger climate policies will hurt their economies by making it more expensive to send food, metals, oil, and other commodities on ships. The Cook Islands, which depends on freighters for essential imports and inter-island transport, worries that it will raise the cost of living.

Advocates say the funds collected from a levy could help lessen any blow to countries that are hit the hardest. Prehn and O’Leary both noted that the proposed $100-per-ton levy is well within the normal price variations for shipping fuels, which can swing between $200 to $600 per metric ton. The industry, in other words, is used to absorbing extra costs when oil prices rise.

Figuring out how the carbon price will work and how funds should be distributed “is going to be a fight,” Prehn said. Proponents hope to reach an agreement by 2023 — a tight timeline by IMO standards.

Under pressure

The brewing carbon price debate comes as the regulator is facing growing public scrutiny.

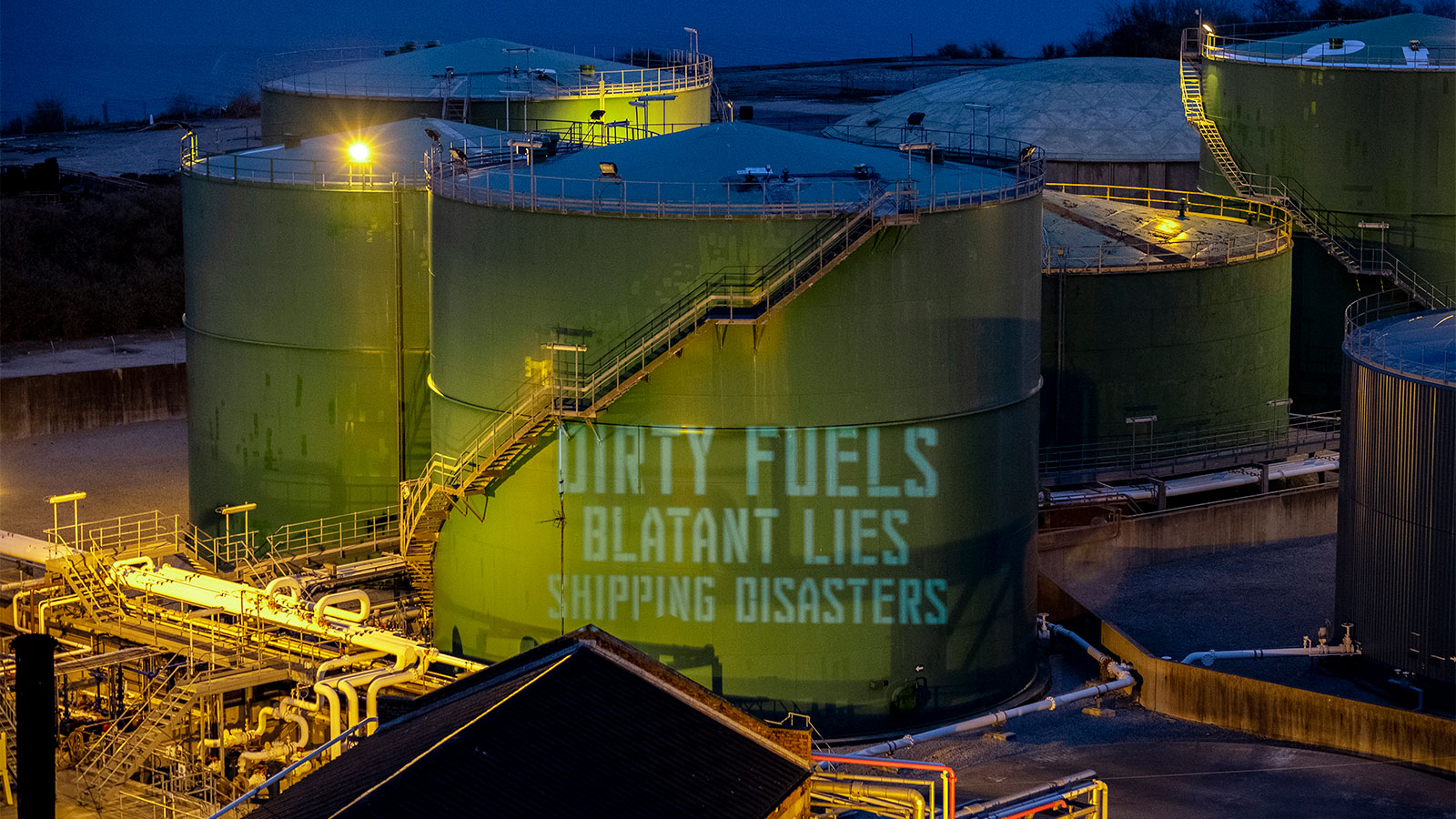

In early June, days before IMO negotiators convened, the New York Times published an investigation that found the U.N. agency has “repeatedly delayed and watered down climate regulations” at the behest of companies and industry groups. And a new documentary by European journalists, called “Black Trail,” accuses the shipping industry of “polluting with impunity.”

European Union officials, frustrated by the IMO’s slow pace, are moving to include cargo ships in Europe’s Emissions Trading System starting next year. The cap-and-trade scheme already limits emissions from power plants, manufacturing facilities, and airlines. Shipping represents a significant share — about 13 percent— of the EU’s total emissions from transportation. Meanwhile, in the United States, the Biden administration said it will push the IMO to strengthen its goals, from cutting emissions in half by 2050 to zeroing them out entirely.

“If the IMO wants to remain relevant, it’s going to have to step up,” O’Leary said.