Josh Fox’s 2010 documentary Gasland alerted legions of people to the dangers of fracking and helped grow the movement against the drilling technique, which has created a natural-gas bonanza in many parts of the U.S. Now Fox is back with a sequel, Gasland Part II, that premiered this week at the Tribeca Film Festival in New York City.

The new film begins much like its predecessor: Shots of politicians alternate with shots of the forest, dripping wet with fresh rain. Fox introduces himself, his home, and his problem: A gas company wants to frack his land and the land around it. But the sequel tells a different kind of story from the first film, and Fox plays a different part.

When Fox first started this project five years ago, he was an avant-garde theater writer and director. After his family received an offer from a gas company to lease his land, he spun his own questions about fracking into a powerful investigative film. Now, three years after Gasland became a sensation, he’s one of the leading activists in the fight against fracking.

In the years between Fox’s two films, that fight has intensified. Big environmental groups (like the Sierra Club) that once worked with the natural gas industry started pushing back against fracking. The Obama administration strengthened its support for the development of natural gas resources. New York keeps delaying its decision on whether to allow fracking; Pennsylvania keeps letting the industry get away with doing pretty much whatever it wants. Whether to frack or not is no longer a good-faith policy debate. The two sides are engaged in “a war for who was going to tell this story,” as Fox puts it, and it’s escalating.

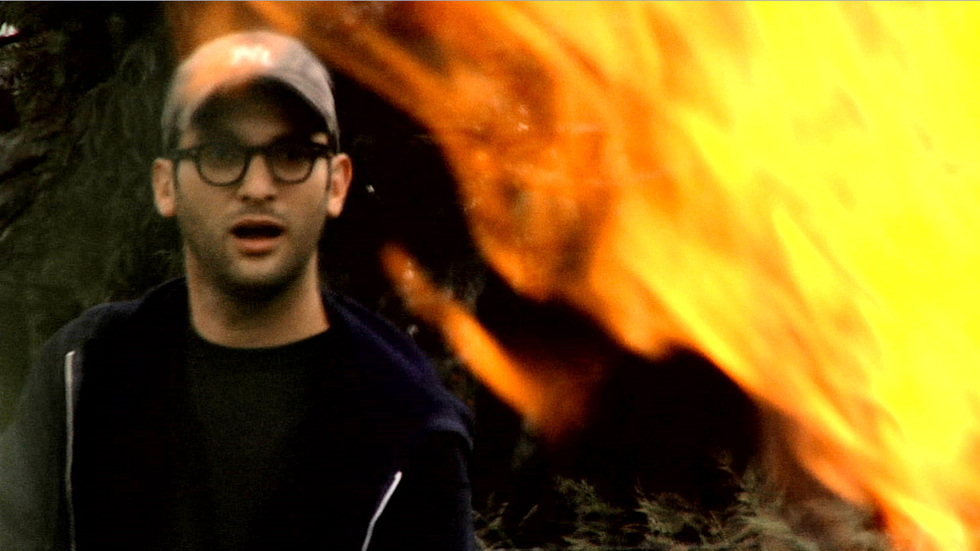

The most compelling images (and some of the most contested) from the first movie were shots of flaming taps. In the new movie, they’ve been replaced by flaming hoses and pipes, which don’t flash briefly but burn until they’re doused. Drilling executives talk about using psy-ops techniques against activists, and families who had hoped the government would push the industry to provide clean water or clean up their mess are giving up and moving away.

Most people will have to wait to see the film until the summer, when HBO will air it, but Gasland Part II doesn’t report much that will be new to anyone who’s been following the fracking fight. What it does show is how that fight has changed and how high the stakes have become for those in it. At this point, with both sides dug in, Gasland Part II probably won’t create as many new recruits as its predecessor. But it could inspire fracking opponents to fight harder and take more risks.

Over the span of Gasland and Gasland Part II, Fox follows roughly the same course of development as the anti-fracking movement he chronicles. In the first Gasland, he was not quite as sure of himself. At one point, he asks, “Was I going to become some sort of natural gas drilling detective?” When he’s handed a jar of contaminated water by a family that won’t identify itself, he’s surprised that anyone is “buying this act of me being a documentary filmmaker” — a person who might be able to expose wrongdoing. He’s just starting to learn that holding a camera gives him power.

Gasland is a classic quest story, where the hero leaves home in search of answers. As Fox learns the truth, the movie’s viewers do, too. Like him, many were persuaded that fracking was a problem, galvanized into worrying about it, and impelled to starting taking action against it.

Fox plays a new role in Gasland Part II, one he’s more confident about. He identifies himself as a journalist and a storyteller. When he’s on screen, he is often playing the part of the documentary filmmaker, camera in hand. The movie’s jumpy style can make it feel like a horror flick, in which Fox plays the character who had the best chance of escaping the killer. By the end of Gasland Part II, many of his comrades-in-arms have been cornered and have taken gas companies’ settlements, which come along with non-disclosure agreements and gag clauses. His friends send psalm citations before going “radio silent,” or practice not responding to questions in front of the camera.

Included in this enforced silence are mid-level EPA employees, who, landowners say, warned that “Off the record, we recommend that you don’t drink your water,” even after the agency had officially declared it safe. It’s clear that Fox sees part of his purpose as continuing to speak while others fade into silence.

But like his friends, Fox is facing pressure to quiet down, too. The film omits Fox’s own skirmishes with the gas industry, which has worked hard to discredit him. Gas companies and their allies are a little bit obsessed with the first Gasland and with Josh Fox. They’ve argued with his facts and waged a campaign again his Oscar nomination. In Truthland, an industry-financed film positioned as an alternative to Gasland, Shelly Depue, a Pennsylvanian mom and farmer, embarks on a parallel quest, and every few minutes, after hearing from another regulator or industry expert that fracking’s fine, Depue will reiterate, “That’s not what Josh Fox said.”

During this week’s Gasland Part II premiere, pro-fracking farmers have shown up in New York to protest the film. On the street after the second showing, the one I attended, Fox, his team, and a couple of landowners featured in the film were drawn into an argument with critics tense enough that everyone involved unholstered their iPhones and started recording.

These obsessions help explain the oppressive, charged environment of Gasland Part II. But if you were watching the film without this knowledge, you wouldn’t know that Fox has been under attack — there’s one brief reference to a PR firm buying his name on Google. He focuses on landowners’ problems, not his own.

What you can see is Fox getting frustrated with the role of filmmaker. Late in the movie, he goes to shoot a congressional hearing and he’s told he can’t record it. He argues that he can. He’s arrested.

At this juncture, he finds more power in the act of resistance than in the act of informing. “The last thing I ever want to do again is tape a goddamn hearing,” he says: They’re often dull. You have to stand for a long time. The lawmakers and witnesses make nasty, infuriating comments. Being arrested, “I felt free,” Fox says. “I didn’t have to listen to what these people were saying about my friends in Wyoming. I didn’t have to do anything else. This was the most I could do.”

At the police station, an officer hits him up for a part in his next movie.

But Josh Fox isn’t just making movies. He’s campaigning, against gas and, increasingly, for an alternative. Gasland Part II hints at an argument for renewable sources of energy. After the screening, Fox got on stage and encouraged the audience to contribute to the cause by “signing up and doing your part” to keep fracking from coming to New York. But he also told the audience to watch for a coming “solutions project.”

The anti-fracking movement has moved beyond simply aiming to educate people. Like Fox, increasingly, activists are tired of listening to what their opponents are saying and are trying to stand in places that the industry and politicians would rather they not be — in front of gas compressor stations, on trucking routes, at fracking waste sites, in state agencies, and on gas drilling sites. Perhaps Gasland Part II will convince more people to join them there.