Officials in Texas continue to investigate the cause of the explosion last week at West Fertilizer that killed 15 people and injured 200. The explosion, which could be felt up to 50 miles away, obliterated the facility and destroyed houses. It was fueled by a massive stockpile of nitrogen fertilizer — up to 270 tons of ammonium nitrate, a solid fertilizer that comes in the form of a powder or pellets, and over 50,000 gallons of anhydrous ammonia gas.

But while the explosion last week was spectacular and tragic, the lives lost there and the pain the community of West, Texas, is suffering offer a window into a much larger battle concerning the overuse of nitrogen fertilizers on American farmland.

In 1909, when German chemist Fritz Haber demonstrated a process that synthesized ammonia, the main component in what was to be known as synthetic nitrogen fertilizer, it was considered a miracle. He pulled the stuff from the air, no less! He and another German scientist, Carl Bosch, who figured out how to produce ammonia at an industrial scale, won the Nobel Prize in chemistry.

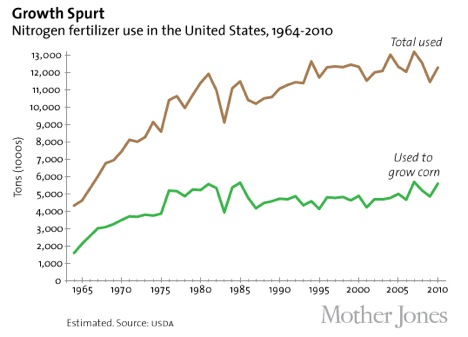

In the century since, synthetic nitrogen fertilizer has displaced the traditional techniques farmers used to increase soil fertility like cover cropping and livestock manure. (Tom Philpott at Mother Jones has an in-depth look at the history of nitrogen fertilizer’s development and use.) Today, U.S. farmers apply over 11 million tons of nitrogen fertilizers to farm fields every year, mostly in the form of ammonium nitrate. The widespread use of the substance is considered part of the so-called Green Revolution, which radically increased the amount food we could grow.

The problem is that a lot of that fertilizer is wasted — more is applied than plants can absorb — and it washes out of the soil into waterways, or evaporates into the atmosphere in the form of nitrous oxide, a potent greenhouse gas. Grist ran a series on the subject in 2010 with the prescient title “Is America fertilizing disaster?”

While the series did not address the risks of explosion associated with storing nitrogen fertilizer, it did describe the main environmental and health risks. They include threats to climate, to human health through nitrate pollution in drinking water, to fish and other wildlife through fertilizer run-off causing low-oxygen “dead zones” throughout the U.S and the world, and to soil health and thus long-term agricultural productivity.

Since we published that series, the data continue to come in regarding the harm excess nitrogen fertilizer can cause. It’s poisoning the water supply of whole communities in California’s Central Valley — enough so that the state is in the early stages of more strictly regulating its agricultural use.

Nitrogen fertilizer’s precise climate impact — which back in 2010 remained unclear — has also come into focus. Nitrous oxide in the atmosphere has risen by 20 percent since the Industrial Revolution, with a good part of that increase coming in the last 50 years. Researchers recently determined that the steep increase in nitrous oxide since the 1960s is almost entirely due to the use of nitrogen fertilizer. Atmospheric carbon dioxide rates have increased around 40 percent in the same period, but nitrous oxide is around 300 times more potent as a greenhouse gas. And it’s also a major ozone-depleting chemical.

This is especially tragic when you look at this Mother Jones chart and realize that nearly half of the nitrogen fertilizer used in the U.S. goes specifically to growing corn:

What this chart should tell you is that if we grow less corn, we’ll use less nitrogen fertilizer. The benefits of that would be significant — and not just to those who live within a stone’s throw of a fertilizer storage or production facility.

I’ve written at length about agribusiness’s reliance on corn, along with the government policies that continue to prop up production. Weaning farmers off corn won’t be easy, since the entire U.S. agricultural system seems designed to support it. It’s not that there aren’t alternatives that can work within our industrialized system. But we need farmers and politicians to accept that too much corn and too much fertilizer is a bad thing. And right now, as they say on MTV, too much is never enough.

At the moment, Mother Nature seems to be doing a fine job of encouraging farmers to plant less corn: In the wake of last year’s crop-killing drought, heavy rains and flooding in the Midwest have delayed planting and threaten the early corn crop. But bad weather and an unstable climate are only going to make the problem worse in the long term. We instead need farmers, government officials, and regulators to step up and admit we have a massive problem with nitrogen fertilizer pollution — and then take the next difficult step and do something about it.

And therein lies another lesson we can draw from the tragedy in Texas. West Fertilizer had evaded regulatory scrutiny for years — as one member of the House Homeland Security Committee put it, the company was operating “willfully off the grid.” This is a problem when you’re dealing with a substance that, when part of an explosive device, is classed as a WMD. The line between a true accident and negligence can be hard to discern, but when a company operates in a legal grey zone for decades and then has a horrible accident, it’s not unreasonable to expect negligence was involved.

Should investigators find evidence of negligence in West, Texas, one hopes the perpetrators will be brought to justice. But it would be a better legacy of the disaster — though admittedly, an unlikely one — that what one analyst called a “massive failure of the regulatory state” could in turn bring greater scrutiny not only to how nitrogen fertilizer is stored, but how it’s actually used.