When he took office two years ago, Washington Gov. Jay Inslee (D) was hailed as the nation’s greenest state leader. He ran on climate change and clean energy — even wrote a book about it — and pledged to make Washington California’s equal in green progress.

He faces an uphill battle. In last year’s midterms, Republicans kept the Washington state Senate and gained seats in the House. If they are organized, they can block any legislation he proposes. He faces a court order to fully fund the state’s education system and a bitterly contested, chronically underfunded transportation system heavily biased in favor of cars and highways.

Now he’s gone the offensive: Last month, Inslee unveiled an ambitious policy agenda anchored by two interlocking pieces. The first is a carbon cap-and-trade system, the revenue from which will be divided among transportation, education, and assistance for low-income Washingtonians and affected industries.

The second is a 10-year, $12 billion transportation plan. It is funded by a combination of carbon revenue and more traditional sources — the gas tax, license fees, etc. The carbon-funded portion of the transportation bill will be devoted to low-carbon alternatives (transit, electric cars, etc.) and maintenance, while new highway construction will be funded from the other sources.

When I met with him last Wednesday (his special assistant on climate and energy, Keith Phillips, sat in), I asked Gov. Inslee about why he chose cap-and-trade, how he determined his transportation priorities, and why he believes the political moment is right. This is our conversation, edited for length and clarity.

—

David Roberts: The climate task force you assembled [last year] put forward two alternative funding proposals: one, a cap-and-trade program, and the other a carbon tax. There’s a pretty vocal constituency in Washington for the carbon tax. Why go with cap-and-trade?

Jay Inslee: Because it works. Climate change is ravaging my state, it’s threatening my grandchildren, and I need something that works. If you’re going to limit carbon, you should limit carbon. Don’t bring a feather to a knife fight.

A [carbon] tax has a benefit of being simple to understand and easier to implement, but it has a huge detriment: It doesn’t give you the most important tool to limit carbon pollution, which is a limit on carbon pollution.

Sometimes people think [a carbon tax] must be better because it sounds harder, you know? We want to demonstrate our bona fides, take the most bitter medicine we can think of, because it must work better. But it just doesn’t. Frankly, if you go just the taxation route, the numbers you have to get to really change behavior and investment are not politically tenable. They’re just not.

DR: I think it’s $174 a ton by 2025. [I was wrong: it’s $172 a ton by 2035. That’s how high a carbon tax would have to be to hit Washington’s carbon goals in the absence of other policies, according to figures from the Washington Carbon Emissions Reduction Taskforce. Details in a footnote at the bottom.]

JI: The fundamental reason [to choose cap-and-trade] is, having a cap is really powerful. It’s the thing that can guarantee my grand kids they will have cleaner air.

Once you have a cap, how do you distribute the licenses, if you will, for that pollution? There are two ways to do that. You can have the government do that, to decide through some system, maybe based on history, who gets the licenses. But that’s just not an acceptable way to do it, because the economy changes too fast. So the other kind of mechanism is the market mechanism, an auction, which we have proposed.

We think we are in a very lucky spot in that we’re early enough in this to be important, to help lead the rest of the world, but we’re not the first. So we’re able to learn from other jurisdictions. We’ve looked at what has happened in Europe [with its cap-and-trade system], the excess volatility they had early in the market, and we have mechanisms to deal with that. We’ve looked at the response in market conditions to how you recycle the dollar, through our program to help low-income people. We’ve looked at measures to help energy-intensive industries. We’ve learned from those experiences. We’re really in a good spot to be able to say, you know, somebody else developed the steam engine here, and now we’ve got the second edition that we can use.

DR: So all the permits are auctioned, from the beginning?

JI: Yes.

DR: If you’re successful in reducing carbon, doesn’t the carbon revenue go down? And threaten your funding?

JI: No, because you reduce the cap over time, so demand goes up. You don’t actually reduce revenue. But individually, those companies make decisions, and the ones that are most successful are the ones with the least cost to pass on to their customers. Those that are most virtuous can reduce the cost of their product to the consumer. It’s a virtuous cycle.

We have built in a way to recycle some dollars back to low-income people, to cushion the costs associated with this, but the costs associated with this are minimal. Literally, pennies or less on an annual basis. What they’ve found in the Northeast [with the RGGI cap-and-trade system] is that the cost, as far as utility rates, you almost couldn’t find it. They’ve been successful in inspiring industrial decision makers to reduce carbon. That’s why they’ve been so successful at minimal cost. Because it inspires people to be smart.

Keith Phillips: On the carbon tax, at least the British Columbia model, a lot of proponents like the idea of the revenue being given back directly [through cuts in other taxes, or as dividends], so it’s revenue neutral. A carbon tax that is revenue neutral versus a trading program that generates revenue for the states’ priorities — two different theories. We don’t think the votes are there for the revenue-neutral carbon tax.

DR: But what you hear from carbon-tax advocates is that the revenue neutrality is what sells it, makes it more politically tenable.

JI: Our review is that that is not the case. My conclusion is that a revenue-neutral proposal does not give you additional support either in the legislature or in the public. It actually has diminished support. That’s from a guy who’s been in this business for 22 years, and both won and lost elections. It’s important to listen to people, and I’ve listened to people and that’s the conclusion that I’ve reached.

DR: Is the intent to hook up [Washington’s cap-and-trade system] with California’s?

JI: Yes. It is very viable and promising for us to have a West Coast coalition. And when we do that, we will represent either the sixth or seventh largest economy in the world. That’s a lot of clout to bring to the international discussion.

The four executives on the West Coast [the governors of California, Oregon, and Washington, and the premier of British Columbia] have signed a working [memorandum of understanding] on how to move forward on this. The West Coast is a place where a lot of good ideas start that sweep the nation. This is the time and place for us for to do it again.

People who haven’t yet embraced action on carbon have abandoned, at least publicly, the climate denial. The fallback position is that we have no bearing on this outcome. We’re helpless. The fact that we have the sixth or seventh largest economy in the world doing something about this — it’s important that folks know.

But I also talk about this from a standpoint of moral obligation. People think they can’t do anything about it individually, we can’t solve it just with one state. Just like my dad couldn’t defeat fascism alone. He needed some other people. But he stepped up to the plate and joined the Navy during World War II. I think there’s a similar moral obligation on us as a state to act.

DR: Is part of the reason you want to use some carbon revenue for transportation that the use of gas-tax revenue is constitutionally restricted? Do you think it gives you more leeway and freedom? [The Washington Constitution says that fuel-tax revenue must go to “highway purposes.”]

JI: Not so much, actually. It’s even a little bit to the opposite. The pro-road-building part of the community is very wary of [gas taxes being diverted from highway purposes], so we’ve been sensitive to that. Almost dollar for dollar, the amount that will be generated from transportation fuels will go back into transportation projects.

DR: So the gas-tax money is going where the gas-tax money would’ve gone anyway?

JI: Essentially. In our plan, carbon dollars go into the segment of our transportation plan dedicated to less carbon-intense systems — transit, maintenance, safety, bike lanes, trip reduction.

So we’re having the best of both worlds. We can tell the transportation community honestly that pretty much dollar for dollar, the money that comes out of the transportation sector will go back into transportation. We can also tell the community that understands we have to reduce carbon that those [carbon-revenue] dollars are going into the part of our transportation sector that’s less carbon-intensive. We think that’s the sweet spot.

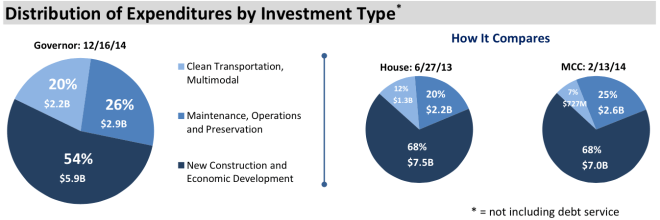

DR: Over 50 percent [of total funding in your transportation plan] goes toward new construction, new highways and bridges; about a quarter goes to maintenance; and about 20 percent goes to transit alternatives. That’s not radically different to the apportionment of transportation funding we’ve seen in the past. If this is an opening gambit, why not go a little bigger on trying to shift the balance to low-carbon alternatives?

JI: Again I want to distinguish that the dollars coming from our carbon policy, those dollars are all going into low-carbon systems. The portion going to new pavement, new lanes, completion of [State Road] 520, and some other things … that is financed by other mechanisms. I want to make sure there’s a distinction.

DR: But it’s just a big pool of money, right?

JI: That’s true, but it is still important to people, and I want to make sure people understand it.

The total pool is a little greener, if you will, than previous iterations. It is a little more aggressive. I wouldn’t say a huge amount. You know, these are always judgments of desires and reality. We made a decision we think can help tug reality a little closer to our desires, but not so much that we break off the conversation. And that’s always a hard decision.

I think people understand that if I was writing, individually, a transportation budget, it would have a more transit-oriented approach. There’s no question about that. But I gotta get a package through here. We have an aspirational but reality-based proposal here.

[The governor’s office sent along a one-sheet that includes this comparison with other transportation plans.

“House” refers to the transportation package passed by the Dem-controlled House last year. “MCC” is the Majority Coalition Caucus, basically the GOP with a couple of aisle-crossing Dems.]

“House” refers to the transportation package passed by the Dem-controlled House last year. “MCC” is the Majority Coalition Caucus, basically the GOP with a couple of aisle-crossing Dems.]

DR: In 2009, the Democratic-controlled [Washington] legislature failed to pass [then-governor Christine] Gregoire’s cap-and-trade plan. Since then, the legislature has become more conservative. It’s more conservative today than it was even last year. What makes you think you can crack that egg?

JI: Several things. No. 1, our plan is in a sweet spot to solve multiple challenges in the state, not just one. Republicans and Democrats alike understand our challenge to finance education. Increasing numbers understand the need to finance transportation. We have now given them a way to do that, by having polluters pay for pollution rather than people pay extra taxes when they buy a pair of tennis shoes. And at the same time, we’re cleaning up the air.

I’ve been pleasantly … not surprised, but pleased at the response to date. People understand that if you are going to spend a dollar on the classroom, why not also get cleaner air for your children? If you’re going to help a kid get early childhood education, why not also help them get an atmosphere to breathe for the next 100 years that doesn’t fundamentally degrade the state of Washington? So it is a two-fer, an additional benefit for the same investment. I think that has appeal to people, regardless of ideology.

Second, I think that the catastrophic events we are now witnessing with our own eyes — forest fires in Okanogan, the slides, the flooding, the lack of snow in places — this entire issue has moved from one that reposes in scientific journals to people seeing it with their own eyes, experiencing it in real life, in real time. That has changed the discussion.

I’m pleased that some of the Republican legislators who have responded to this [plan], their rhetorical response has been very different from what it was four or five years ago. Four or five years ago, this was not a problem, we can ignore it, it’s a hoax. That’s changed; you don’t hear that as much now. You hear sincere questions about how our plan would work, which is good. This is a new idea to a lot of people.

I think my Republican colleagues understand that it has become untenable any longer to be climate deniers, facially, and vocally, and subject to direct observation.

DR: They’re not scientists.

JI: So they’ve searched for another way, and now they have questions about the kind of things we’re proposing, which is good. Now we’re talking about how to solve it instead of whether to solve it. That’s a good shift and I welcome it.

The easiest thing to answer is that [legislators] are going to be desperate for a dollar to try to solve our problems. And we’ve provided them with a way to do it that is paid for by polluting industries.

DR: Has framing it primarily as a funding mechanism and only secondarily as climate policy changed the way it’s been received?

JI: I think it has. And that’s healthy, because it’s real and it’s honest. This is not a shell game, this is real dollars for real problems.

DR: You have this court mandate that education needs to be funded better in Washington; you have this crisis of transportation funding; you have this legislative mandate to reduce carbon. Your plan — cap-and-trade with revenue going to education and transportation — addresses all those, but it all hinges on the cap-and-trade proposal. So if the Republicans in the Senate refuse to pass a cap-and-trade proposal, what is plan B? Where does the money come from?

JI: That’s for writers to write about, but not for me to consider. I’m not bidding against myself. This is an elegant and commonsense solution to multiple problems. One, it’ll work on carbon; two, it’ll generate significant revenues for the educational fund; and three, it does transportation.

Seldom do you have, in public life, something that will solve three major problems at one time. We’re in a lucky place in the state of Washington. We have massive financial challenges, but we also have a tool sitting in our toolbox. All we have to do is pick it up and turn this carbon wrench and it’ll solve all three problems. That is a rarity. It’s a no-brainer, and the best evidence I have that it’s a no-brainer is that I thought of it.

—

* Here’s the relevant bit about how high carbon taxes would need to be to meet the state’s climate goals, from the Washington Carbon Emissions Reduction Taskforce report:

The preliminary analysis looked at two scenarios modeled starting in 2015: a low carbon price scenario beginning at $12 a ton (approximately the current price in the California market) and increased $.60 annually through 2020, and by $2/ton annually thereafter until 2035; and a higher carbon price scenario ($12 a ton in 2015, increasing by $8/ton annually thereafter). The higher price scenario reflects the CTAM model’s estimate of the price levels required to meet the State’s statutory emission limits for 2020 and 2035, assuming price was the sole driver of emissions reductions and no price volatility as a function of market manipulation or other factors.

$12 a ton in 2015, increasing $8 a year, gives you $172 a ton in 2035. Again, that’s assuming Washington carbon targets are met purely through a carbon price, with no complementary policies.

—–

See also: Inslee on Seattle tunnel: “No one is more frustrated by this project than I am”