Earlier this year, the seven states that depend on the Colorado River made history. For the first time, Arizona, California, Utah, Nevada, Wyoming, Colorado, and New Mexico agreed to find ways to reduce the amount of water they draw from the river as levels drop further at Lake Mead, the largest reservoir in the country.

The Colorado River provides water for 40 million people. But its flows are shrinking as the planet heats up, reducing the snowpack that feeds the river and causing more water to evaporate as the river snakes its way from the Rocky Mountains to the Gulf of California.

But even if climate change weren’t an issue, the Colorado would probably still be in trouble. Back in 1922, when states originally divvied up water from the river, they grossly overestimated the amount of water flowing through it. This set in motion a series of decisions that led to the shortages today. States are dipping into Lake Mead’s reserves, overdrawing 1.2 million acre feet of water annually — enough to quench the thirst of a couple million households for a year.

As conventional wisdom has it, the states were relying on bad data when they divided up the water. But a new book challenges that narrative. Turn-of-the-century hydrologists actually had a pretty good idea of how much water the river could spare, water experts John Fleck and Eric Kuhn write in Science be Dammed: How Ignoring Inconvenient Science Drained the Colorado River. They make the case that politicians and water managers in the early 1900s ignored evidence about the limits of the river’s resources.

In 1916, six years before the Colorado River Compact was signed, Eugene Clyde LaRue, a young hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey, concluded that the Colorado River’s supplies were “not sufficient to irrigate all the irrigable lands lying within the basin.” Other hydrologists at the agency and researchers studying the issue came to the same conclusion. Alas, their warnings were not heeded.

I caught up with Fleck and Kuhn to learn why LaRue and others were ignored and what history can teach us about the decisions being made on the river today. This interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Q. When did you both realize that the conventional wisdom about the framers of Colorado River law using bad data was incorrect? Was there an “aha” moment?

A. Fleck: The “aha” moment for me was when I found the transcripts of LaRue’s 1925 congressional testimony, when he said, as clear as could be, that there’s not enough water for this thing they were trying to do. It erased any doubt I had that the reports were too technical and people didn’t really understand them. He was there testifying before Congress, and they just chose to ignore it. None of the senators followed up. They were clearly choosing to willfully ignore what LaRue was saying.

Kuhn: He wasn’t alone. There was USGS hydrologist Herman Stabler, an engineering professor from the University of Arizona, and a very high-level commission appointed by Congress, headed by a famous Army Corps of Engineers’ lieutenant general, and they came to the same conclusion. The surprise to me was how widespread the information was among the experts at the time. There was never even enough water in the system for what we wanted to do before climate change became an issue.

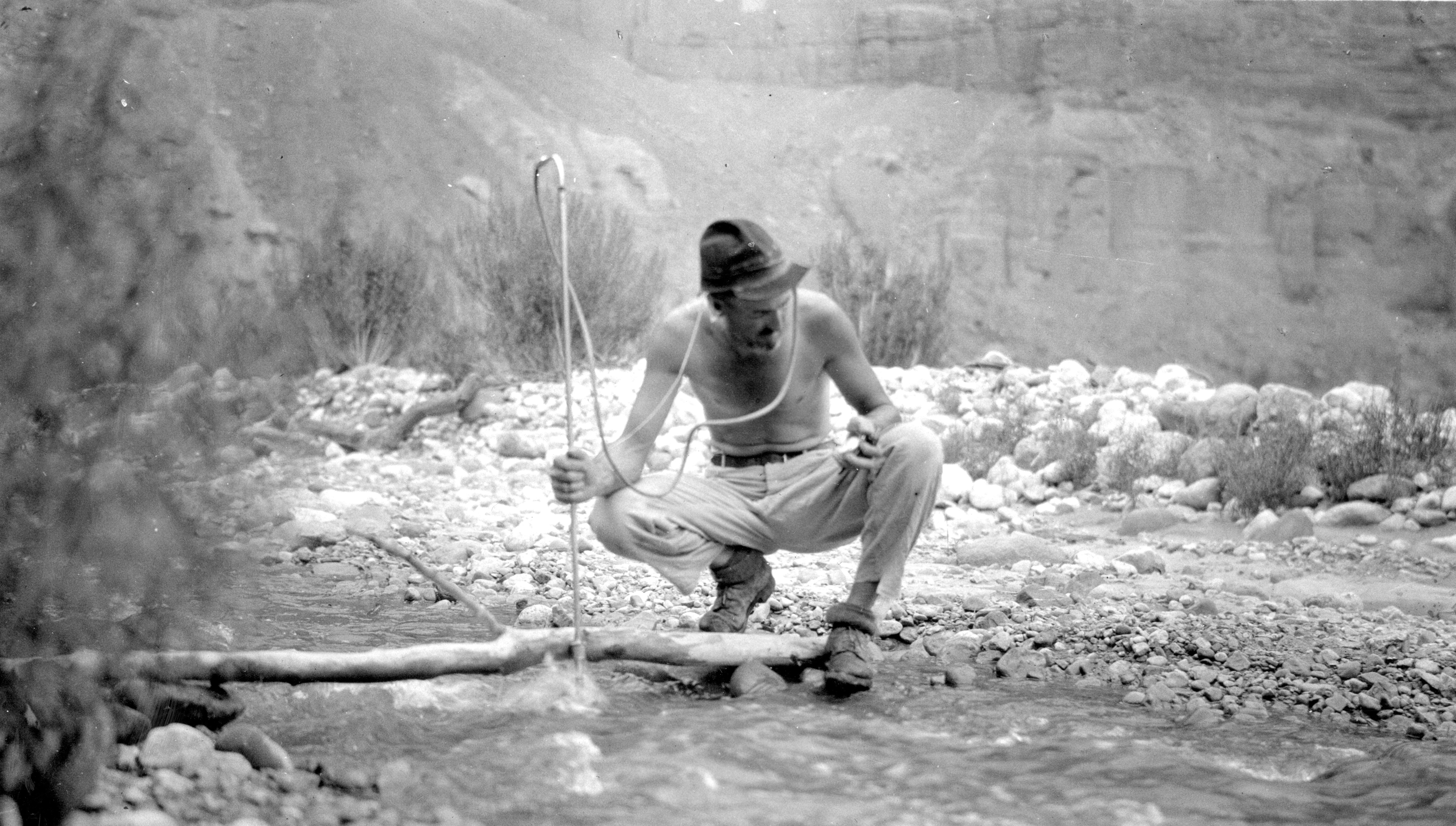

USGS hydrologist Eugene LaRue gauges the flow in Havasu Creek, a tributary to the Colorado River. USGS

Q. So why didn’t people listen to the researchers?

A. Fleck: The short-term incentives were always to pretend that there was more water so everybody can build the stuff they wanted to — dams, canals, cities, and farms. Everyone knew, if they were being realistic, that the problems would fall on future generations. People were not as invested in the future as they were in the present.

Q.Some states are still considering building dams and pipelines to draw more water out of the Colorado. Do you think we’ve learned our lesson?

A.Kuhn: I think we’ve learned from history, but we haven’t had an opportunity to apply that to making some practical decisions. In the past, most of the states except California were dependent on federal money in Congress. You have to put together coalitions to get projects through congressional appropriations. It was much easier to divide up a larger pie politically than it was to deal with reality.

Today, congressional appropriations are still important, but new projects are largely being handled by the big municipalities or the states, like Utah’s Lake Powell pipeline. This coalition process that worked in allocating the river, in providing money and water — now we’re overusing that water, and we’re probably going to have to shrink what people are getting. What’s the process? There isn’t one.

If you don’t start thinking about that basic problem, we’re not going to get the job done. It’s still very difficult to sell back home to state legislators and governors, because they’ve been told we still have extra water.

Q. Do you think data is getting ignored in the Colorado River basin today?

A.Kuhn: One place where the data is being ignored is with municipal demands. Las Vegas today is serving 40 to 50 percent more people with less water than it was in 2003. Denver Water has doubled the size of its service area with about the same amount of water it was using in the early 1980s. Demands have been going down. We’re much, much more efficient in how we use water, and that has yet to get into the culture of the basin.

Case in point is the 2012 Colorado River Basin study by the Bureau of Reclamation. Almost all the states took the same position they did in 1922, which was “Well, we need more water.” They ignored what was happening back home and went back to traditional game theory — if you’re going to be negotiating with somebody, you’ve got to overstate your demands.

Fleck: On the positive side, we are seeing planners be much more effective at developing the tools to incorporate an analysis of climate change risk into the modeling. But the flip side is that you have a bunch of water users who are really uncomfortable with being realistic in their assessment of the fact that their needs are declining and their water supply is declining. So, it’s getting the science message to permeate that political barrier in the same way that it was difficult back in the 1920s.

Q.The last line of the book says that with climate change, there’s less and less water, and “we don’t know how far below us the floor lies.” How do you plan for the future if you don’t know where the bottom is?

A. Kuhn: The continued reliance on this concept of an entitlement that was based on a much different river has to go away, and the management has to become more flexible. We spent a hundred years slicing the pie and giving everybody a piece. In the next hundred years, we’re going to have to put the pie back and make a new one. The legal entitlements add up to more than what’s in the river, and the management system is designed on meeting those legal entitlements. That has to fundamentally change. There has to be a paradigm shift.

Fleck: I’m optimistic about our ability to do this. We have seen the development, over the last 20 years, of the tools we need to begin to solve this problem. We’re seeing municipalities use less water. We’ve seen agricultural water users be very successful in recognizing the opportunities presented and not trying to cling to these old allocations and this “water is for fighting over” myth.

We can do this if we can negotiate some collaborative pieces together. If, alternatively, we cling to the old water allocation rules that were written a century ago, and everybody digs in their heels and says, “Yeah, but I need all that water,” then the whole thing could blow up, and it would be a catastrophe in the West.