In the summer of 2020, the liberal city council of Flagstaff, Arizona, passed a resolution to achieve carbon neutrality by 2030, tasking the city’s sustainability office with figuring out a plan to get there.

The agency’s small team got to work gathering input from the community and modeling different options for reducing emissions. But the tight deadline backed them up against a wall. The best plan they could come up with, one that felt both ambitious and realistic, would only lower emissions by 44 percent by the end of the decade. That’s how Ramon Alatorre, Flagstaff’s climate and energy coordinator, found himself in front of the city council last May, arguing that Flagstaff would need to do something that few other local governments had even contemplated — it would need to balance out those emissions by sucking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.

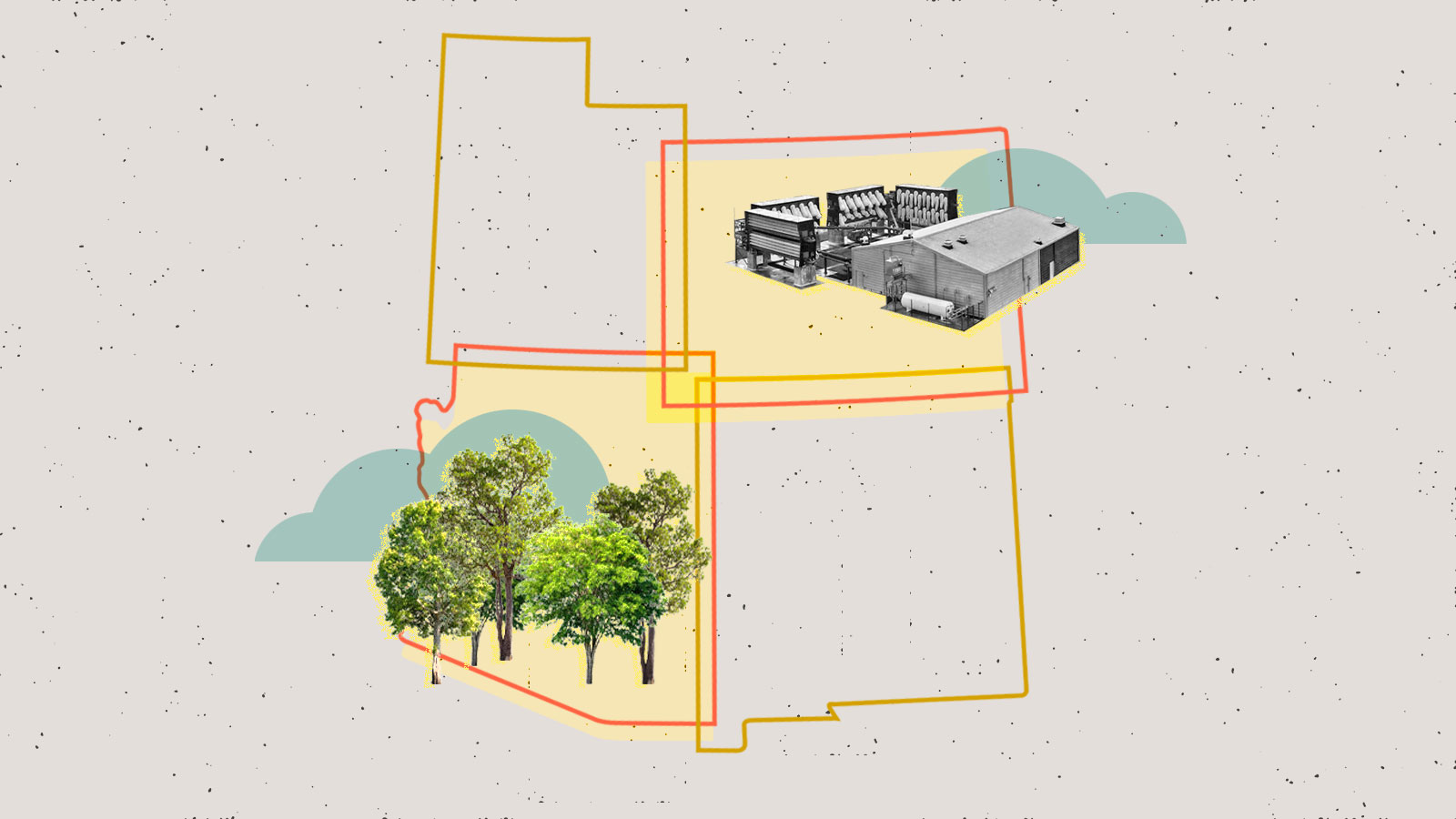

Delivering a PowerPoint over video conference, Alatorre described various approaches to drawing down carbon from the atmosphere, including planting trees and restoring ecosystems, crushing up minerals in order to enhance their carbon-absorbing properties, and building futuristic factories that pull in large volumes of air, separate out the carbon dioxide, and send it to underground storage sites. He warned the city council that most were still in early stages of research and development and were expensive.

“We cannot delay when it comes to developing carbon dioxide removal,” he said. “It will take time to scale, and there will be barriers to navigate.”

The city council was convinced. Two weeks later, Flagstaff became one of the first cities in the country with a climate action plan that included carbon dioxide removal, or CDR. But Alatorre’s presentation also resonated far beyond Flagstaff’s borders. A few months later, he was talking with Susie Strife, the director of sustainability in Boulder County, Colorado, who heard about his presentation and was also working on starting a carbon removal program.

Now, Flagstaff and Boulder County are teaming up to form a coalition of local governments that will pool resources to fund CDR projects in the Four Corners region. By working together, Strife and Alatorre hope not only to help grow the carbon removal industry, but also to give local communities a say in the deployment of these projects, which can come with myriad tradeoffs and risks.

“If we’re not involved, we’re sort of at the mercy of whatever those that are involved are putting in place as their guardrails, or their parameters,” Alatorre told Grist.

To date, the development of carbon removal has largely been steered by a few big tech companies like Microsoft, and billionaires like Elon Musk, that are funding early-stage projects. Interest in CDR began to grow after a 2018 report by the United Nations’ panel of climate scientists said the world would need to remove a lot of carbon from the atmosphere, potentially billions of metric tons per year, to achieve the Paris Agreement’s goal of limiting warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit.)

Alatorre and Strife want their communities to be climate leaders, but CDR is hard to tackle on a limited municipal budget. “If one local government tries to do this on their own, it’s gonna be extremely costly and time intensive, and we don’t have the technical expertise,” said Strife. “We’re trying to aggregate resources and create a sort of a local government platform for CDR.”

The idea for the coalition was, in part, inspired by Strife’s experience forming an initiative called Colorado Communities for Climate Action, a coalition of 40 local governments that collectively lobby for stronger state and federal climate policy. She and Alatorre also likened it to Solarize, a grassroots strategy that has empowered groups of homeowners across the country to pool their demand for solar panels and solicit competitive bids from companies, resulting in reduced costs.

Strife and Alatorre were initially put in touch by members of the OpenAir Collective, a national volunteer network of carbon removal enthusiasts and advocates. Christopher Neidl, an OpenAir cofounder who has been advising the coalition, said that by pooling resources, it can be an engine for more innovative, creative deployment of CDR — solutions with a “high-magnitude upside.”

Neidl compared this strategy to that of Stripe, a Silicon Valley payment software company that has made a name for itself in CDR. Rather than paying for relatively inexpensive tree-planting projects, Stripe has dedicated millions of dollars to buying carbon removal from startups, in many cases as the very first customer to companies that have yet to fully prove their methods, in order to spur innovation and speed up development.

The Four Corners coalition is still in early stages. It has a one-page mission statement that lists a goal of raising $1.25 million to support the removal of 2,500 metric tons of CO2, meaning they could end up spending as much as $500 per metric ton. (Currently, the most expensive forms of carbon removal can cost several hundred to more than a thousand dollars per metric ton.) Flagstaff and Boulder County have together committed $300,000 to start. Boulder will use funds from its sustainability tax, a program that diverts a portion of sales tax in the county toward sustainability programs. Alatorre said his department is contributing funding it received from the federal American Rescue Plan Act, the COVID-19 stimulus package that Congress passed in March 2021.

The coalition’s first request for proposals, which it will issue later this summer, will solicit projects that involve capturing carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and sequestering it in concrete. “Concrete is incredibly distributed, there are concrete producers in pretty much every single community,” said Alatorre. “So if you were to have that be what you build our sidewalks with, that could be really interesting.”

Alatorre and Strife are also excited about other local benefits that carbon removal projects could bring to the region, like job creation and ecosystem health. Both expounded on the potential to take wood debris from overgrown forests and turn it into biochar, a very stable charcoal-like substance. Scientists believe biochar can store the carbon locked in wood and other organic waste for hundreds to thousands of years — and when added to soil, it can potentially improve water retention and yields. Separate from the coalition’s work, Strife’s office recently put out a request for proposals offering $450,000 to support local projects that both remove carbon from the atmosphere and support “landscape resilience and restoration.”

Stefan Sommer, an ecologist who lives in Flagstaff and is on the board of a grassroots climate group called the Northern Arizona Climate Change Alliance, said he was concerned when the city incorporated carbon dioxide removal into its climate plan. “We need to focus more on reducing emissions, given that carbon capture and sequestration has so much uncertainty involved in it,” he said. “I worry about it because it really depends on which avenue they take.”

He mentioned tree-planting programs that were found to be using faulty carbon accounting, the enormous energy use required for air-filtering machines, and the challenges of measuring and monitoring the carbon removed by ocean-based methods, like growing kelp and then sinking it to the bottom of the ocean.

But Sommer was more optimistic when he heard that the coalition planned to look at ways to store carbon in the concrete. “I think that’s wonderful that they’re considering that option,” he said. “That’s something that has the potential to take a little bit of CO2 out of the atmosphere and stop putting a lot of CO2 into the atmosphere, because cement production is about 8 percent of global emissions.”

Sommer isn’t alone in his skepticism of carbon removal. Many climate and environmental justice advocates are worried that chasing after these solutions will detract attention and resources from cutting emissions today — in no small part because some of the largest carbon removal projects in development today are backed by fossil fuel companies. There are also concerns that any potential environmental and economic impacts from carbon removal projects will fall on historically overburdened communities.

A group of researchers recently argued in The New Republic that carbon removal should eventually be a public service, like waste removal, and fully owned and operated by communities. This structure could ensure that CDR is deployed in the public interest, as a source of good-paying jobs, and in a way that is most beneficial to communities. Toly Rinberg, a doctoral physics student at Harvard University studying carbon removal and one of the authors of the piece, is concerned that if carbon removal projects are owned by private companies, the incentives will be purely about carbon and profit, and not about looking out for public health or local economies.

He said that carbon removal is currently so nascent and small-scale that it makes sense for governments to use public money to finance private projects in a way that builds trust in communities. But he wants to see companies and governments alike thinking about how to embed community control early on, so that when these projects scale up 1,000 times, they’ll still align with local priorities.

Alatorre and Strife are hopeful that spearheading projects at the local level will help build more support for carbon removal from the ground up. “We are talking to people who are part of our community and asking what their concerns are, and educating our constituents about it who might be skeptical,” said Strife.

Stephanie Arcusa, a postdoctoral researcher at the Center for Negative Carbon Emissions at Arizona State University who previously interned with the Flagstaff sustainability office, said she’s excited about the coalition because it will give everyday people more exposure to carbon removal, and help ensure that the benefits go straight to the community.

“I don’t think they believe they can cover their entire emissions through their coalition, but maybe that’s a way to reduce costs and catalyze change and make it more visible for the local person,” she said. “I think it’s more of a perception and appearance kind of thing than materially making a difference — for now.”