This story was produced in collaboration with InvestigateWest.

A decade ago climate activist Eileen Quigley found herself in deep despair. Washington, Oregon, and the Canadian province of British Columbia had set ambitious plans to control climate-warming greenhouse gases, but misinformation campaigns by fossil fuel lobbies and a global financial meltdown unnerved legislators, blocking measures to drive the states’ climate plans.

Shut down in Salem and Olympia, the Seattle-based environmentalist and her allies saw their hopes dashed again in Washington, D.C., in 2010. Despite an ascendant Democratic president and a Democratic majority in Congress, a sweeping climate bill died in the Senate and Republicans opposed to climate action took control of the House.

And in B.C., after a bruising provincial election in 2009, a pathbreaking tax on atmospheric pollution, and other climate protections were barely hanging on.

“It was bleak,” Quigley recalled in a recent interview. “There was a lot of anger and definitely frustration and disappointment.”

The result: A region billed as “ecotopia” last century came up way short on the biggest environmental challenge of this century.

Seattle environmental activist Eileen V. Quigley is one of the authors of Washington state’s official plan to nearly eliminate the use of fossil fuels, and expresses hope that widespread public awareness of climate change will drive change. Dan DeLong / InvestigateWest

But 2021 opened with some good news. Quigley claims to be more hopeful than ever.

Exactly 10 years after that Republican majority retook the House, Quigley and her colleagues can point to a new and officially endorsed blueprint for how Cascadia — the eco-friendly region comprised of Washington State, Oregon, and B.C. — can successfully kick the fossil-fuel habit.

Working early on from a converted garage with a balky heater, Quigley toiled for years with her policy shop, the nonprofit Clean Energy Transition Institute, to provide technical assistance in support of Washington state’s energy strategy. The 428-page 2021 remake released earlier this month by the Washington Department of Commerce maps out how to eliminate all but a sliver of fossil fuel emissions through a massive shift to renewable energy.

They are some of the most ambitious climate-protection goals on the planet.

Not only that. For the first time in four years, federal leaders in the United States and Canada both support climate action.

Energy economics also are changing. Cleaner technologies that play the starring role in Washington’s new energy plan keep getting cheaper. These days equipment such as electric vehicles and heat pumps cost less — with fuel included — than their fossil-fueled forerunners. Solar power’s cost has plummeted more than fivefold since 2010.

Suddenly solar installers and other “clean energy” firms provide more than half of Washington’s energy-related jobs. And fossil fuels’ purveyors have less grip on markets — and perhaps even legislatures — as demand for coal, oil, and gas weakens and global protests erode their social standing. “In 2007 we used to talk about Big Oil and King Coal. No one says King Coal anymore, and oil is faltering,” said KC Golden, one of the founders of regional nonprofit Climate Solutions and a board member with international activist group 350.org.

The question now is: Will Cascadia’s governments actually follow through?

Governors Kate Brown of Oregon and Jay Inslee of Washington both have newly tightened emissions goals and detailed road maps to reach them. They are catching a break as carbon-cutting deals clinched years ago close coal-fired power plants. And the governors’ recent moves speak to an emboldened will to act, including a climate-driven decision last week by the Washington Department of Ecology to deny a key permit for a carbon-intensive methanol plant proposed near Kalama.

The challenge is finding dollars in Covid-tightened state budgets to accelerate carbon-cutting. Clean technologies often cost more up front, and it will take state money to speed up their deployment and ensure that all citizens benefit. And in both states, legislators who have long held up cost-effective climate policies remain in their seats.

British Columbia faces a very different challenge. Premier John Horgan’s New Democratic Party secured a commanding majority in fall 2020 elections. But B.C. has a growing oil and gas production industry, including a nascent natural gas liquefaction sector that Horgan has personally championed as a source of jobs and revenues.

King Coal may be dethroned, and Big Oil weakened, but in BC the oil and gas producers and their employees still carry clout, noted Karen Tam Wu, BC regional director for the Pembina Institute, a Calgary-based climate and energy think tank. As Wu put it: “The lure of royalties and the lobbying power of Big Oil is very strong.”

Decarbonization road map

Among the three government’s plans, Washington’s marks the most dramatic shift. The state that set Cascadia’s weakest emissions goals over a decade ago raised its sights to world-class performance early last year. The Legislature scrapped the state’s 2008 mandate, which called for halving emissions by 2050, from 1990 levels — completely insufficient, according to climate scientists. In its place, legislators approved a net-zero goal: only 5 percent of 1990-level emissions would be tolerated in 2050. (And even that 5 percent would need to be recaptured via reforestation projects or machines sucking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere.)

Washington’s new goals are among North America’s most ambitious, and come with interim goals, too, starting with a 45 percent cut by 2030. That will require a lot of push, because recent modeling suggests that Washington could still be pumping out the equivalent of 84 million metric tons of carbon dioxide in 2030. The state’s goal requires cutting emissions to 50 million metric tons.

The Washington State Energy Strategy, released earlier this month, calls for a shift from gasoline- and diesel-fueled vehicles to electric cars and trucks charged up with zero-carbon electricity. To produce that electricity, the plan requires cooperation with neighboring governments including British Columbia and Oregon to accelerate construction of new solar and wind energy plants. Dan Delong / InvestigateWest

The new targets came without new authorities to actually drive carbon cuts, leading critics to declare the 2020 legislative session a “comprehensive failure.”

What the legislature did provide was funding for detailed study. That’s where Quigley’s crew at the Clean Energy Transition Institute, or CETI, swung into action, and quickly. They sketched out how to most cost-effectively transform the economy from fossil energy to clean energy, enlisting decarbonization modelers at San Francisco-based consultancy Evolved Energy Research and seeking advice from over 150 technical experts and community advocates and a 27-member state advisory committee.

No study gets the job done, though. While a 2019 law gives Washington the authority to rapidly decarbonize its electrical system, the state’s plan requires regional action — a massive expansion of power lines connecting Washington to its neighbors to facilitate an equally massive build-out of wind and solar power plants across the Western U.S. and Canada. “We can really do a lot in terms of keeping rates affordable and service reliable if we can operate the electricity system on more of a west-wide basis,” said Glenn Blackmon, head of Washington’s Energy Policy Office.

Other crucial strategies include universal broadband access, smarter community planning, and expanded public transit, all of which can cut down on total travel via personal vehicles. And, for those fossil fuel uses that can’t be easily plugged in, the strategy requires an entirely new industry: green hydrogen produced by zapping water with renewable electricity.

Green hydrogen is a renewable fuel that can be stored and concentrated, providing a reliable stream of clean energy to replace coal and gas burned in concrete plants and other heavy industries, and to replace diesel in big vehicles such as long-haul trucks and ferries.

Energy experts worldwide see green hydrogen as a crucial building block for decarbonization. For Washington, it also offers an economic engine for rural counties, according to Blackmon, who noted that utilities in eastern Washington with surplus hydropower already have “aggressive” plans to make green hydrogen.

It’s all economically affordable. According to CETI’s modeling, spending on energy in a decarbonizing Washington would remain within its historic range, about 5-7 percent of the state’s economy through 2050.

The plan pledges state intervention to ensure that low-income and historically disadvantaged communities have access to capital to upgrade homes and businesses, for example, or to cover the up-front price premium on an electric car. Deric Gruen, co-executive director for Seattle-based climate justice coalition Front and Centered and a member of the plan’s advisory council, praised the state’s Department of Commerce for emphasizing equity. But he called it “unfortunate” that the aggressive timeline for crafting the plan precluded robust public engagement before it was finalized. “The modeling piece is important. But often it can be mistaken for the main dish, which is the politics and the economics and the social transition,” said Gruen.

All signs point to rough politics ahead. Inslee proposed a legislative package late last year with new mandates to drive the action. They include a fuel standard to ratchet down the carbon intensity of Washington’s gasoline and diesel fuels that industry lobbyists have repeatedly fended off, and a ban on natural gas heating in new buildings whose 2030 cutoff date is too late for some activists.

And the governor proposed some controversial means of raising revenues, including yet another push for “carbon cap and trade”– a system of pollution controls and charges that has repeatedly failed in both Washington and Oregon’s legislatures. That has split the Washington legislature’s climate advocates, as climate justice advocates such as Gruen back a rival revenue package combining a carbon tax and economic recovery bonds.

A key part of the decarbonization plan released this month by Washington state is to capture wind power from turbines like these in Oregon and use the juice to produce hydrogen gas that can be stored for later use when the wind isn’t blowing as much. Meg Roussos.

Getting beyond business as usual

Activists say what’s needed, as much as money, is for Cascadia’s leaders to push climate action into every nook and cranny of government policy.

For example, take the new I-5 bridge across the Columbia River between Vancouver, Washington, and Portland, Oregon. Patrick Mazza, a longtime Seattle-based climate policy analyst and activist, sees business as usual at work there. Instead of bolstering rail links to reduce truck traffic, which causes the most damage, the states may build a larger bridge — a move that Mazza predicts will accelerate sprawl from nearby Portland into Washington’s Clark County.

“That is really a poster for the inertia of the past continuing into the present,” says Mazza, the president of 350 Seattle. “We’re not living in a climate emergency world. That has not been absorbed into the day-to-day operations of bureaucracies or most businesses.”

The Seattle-based Sightline Institute think tank recently called out a mismatch between state emissions goals and growth plans from Cascadia’s gas utilities. Washington and Oregon’s largest gas utilities, Puget Sound Energy and NW Natural, anticipate rising gas use through 2040, even though energy planners say it must decline “dramatically.” Burning gas currently causes nearly one-quarter of Washington’s carbon emissions, and more than one-third ofOregon’s.

Angus Duncan, a Portland-based energy policy expert who formerly advised Oregon Governor Ted Kulongoski, agrees that business as usual and inertia afflict Oregon’s Public Utilities Commission, which rules over the state’s utilities.

During an interview last fall, Duncan cited a 2017 decision that flew in the face of the state’s renewable electricity mandate.

Whether and how to expand the Interstate 5 bridge between Oregon and Washington is a prime example of decisions facing the governments of Cascadia about combating climate change. Critics say adding more lanes to the bridge will accelerate urban sprawl north into Washington from Oregon, baking in decades of single-user car trips that further heat the atmosphere. Troy Wayrynen / The Columbian

In 2016 Oregon’s legislature expanded the rules, requiring generation of half of the state’s power from non-hydropower renewables by 2040 — a more than sixfold increase from 2018. But the following year the Public Utility Commission downsized a utility proposal to build the state’s largest wind power plant.

Portland General Electric said building big would save customers money because the project would qualify for soon-to-expire federal subsidies. But the PUC’s commissioners, siding with consumer advocates and the agency’s staff, ruled that the utility had plenty of renewable energy for the time being. PGE went ahead with a smaller project, which began operating in December.

Duncan said the utility commission’s “decision-making processes” served the state well for decades by protecting consumers from unnecessary utility spending, but are ill-equipped to manage an energy sector in transition. “They had a screwdriver and a saw and they needed a computer-driven drill press,” said Duncan.

The good news, wrote Duncan in a recent email exchange, is that Oregon activists and utility officials are collaborating on a “100 percent clean” bill to accelerate action in the power sector. The bad news, he said, is that increased driving and natural gas consumption are where Oregon’s emissions are rising and Oregon “has no strategies for turning these sectors around.”

B.C.’s gassy carbon bulge

Oregon Governor Kate Brown faces many of the same budget and authority gaps that have bedeviled Inslee. Not so across the international border, where Premier Horgan’s parliamentary majority in the B.C. legislature gives him leeway to pass legislation and raise Canadian dollars. However, his government faces a growing gap between emissions and its 2030 goals — a gap that is exacerbated by fossil fuel development.

For nearly a decade, activists across California and Cascadia defeated proposed megaprojects to export Western coal, oil, and gas through Pacific ports. That so-called “Thin Green Line” of activism broke in B.C. in 2018, partly due to Horgan, when three megaprojects got green lights.

One, the Trans Mountain petroleum pipeline expansion, moved forward in spite of B.C.’s objections when Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau nationalized the project, which would triple the flow of carbon-laden bitumen from Alberta to the Port of Vancouver. Horgan took credit for the other two: a $13.4 billion liquefied natural gas terminal up the B.C. coast in Kitimat, and a $5.2 billion pipeline linking it to northeastern B.C.’s gas fracking fields.

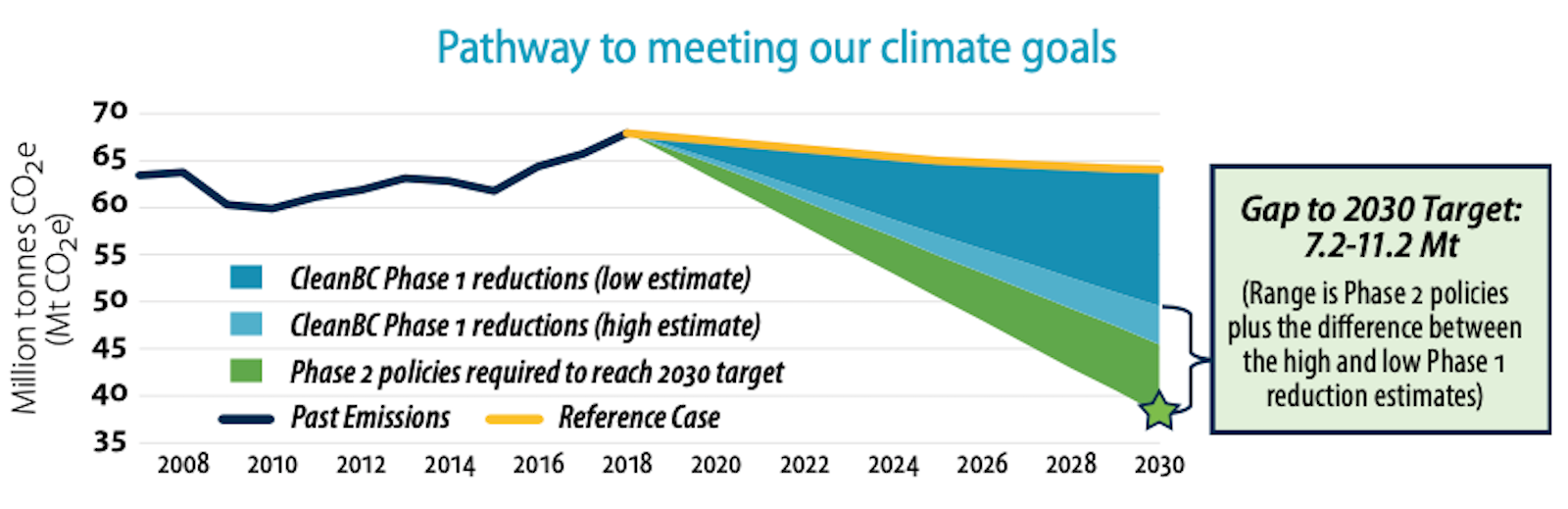

Oil and gas production contributed half of the provinces’ industrial emissions in 2018, and have risen 8 percent since 2007. That’s a significant challenge to the goal, set by Horgan’s government in 2018, to cut emissions 40 percent by 2030 compared to 2007. In December, a government report said rising emissions from industry and transportation meant B.C. could miss its 2030 target by nearly half.

B.C. Ministry of Environment and Climate Change Strategy

Wu at the Pembina Institute, a member of the government’s Climate Solutions Council, called the report “sobering” — not least because the report failed to spell out steps to close B.C.’s emissions gap, as the government had promised.

Calculations by the Pembina Institute confirm the long-term scale of the challenge. It found that the LNG terminal in Kitimat would release the equivalent of 3-4 million tons of CO2 per year, and carbon emissions associated with producing and delivering its gas would add another 5 million tons. That one project could thus produce two-thirds of the greenhouse gases allowable in 2050 under B.C. law.

Continued expansion of “natural” gas harbors a second climate risk: leaks of particularly climate-unfriendly methane. While shifting power plants from coal to cleaner-burning natural gas has slowed the growth in carbon emissions worldwide in recent decades, methane leaks erode some of that advantage. Exporting natural gas as LNG adds still more climate impact because extra energy is used in chilling and shipping. Experts increasingly warn that LNG could soon rival coal as a contributor to climate warming.

Meanwhile, construction of B.C.’s fossil megaprojects has continued during the pandemic as an “essential service” in spite of the risks that their work camps bring to rural communities, and forceful calls from First Nations to shut them down. The construction has exacerbated ongoing tensions with First Nations bands such as the Wet’suwet’en, which sparked Canada-wide protests one year ago.

George Heyman, B.C. Minister of Environment and Climate Change Strategy, offered no apologies during an interview this month with InvestigateWest. He said B.C.’s gas industry, including LNG development, provides revenues for public programs and jobs. “We thought there was some room within a credible climate plan for some development and we approved [LNG Canada] on that basis,” said Heyman, adding that any further projects will have to fit within a sector-specific emissions target to be set by the end of March.

And he noted the emissions-cutting programs legislated in 2018, in partnership with the Green Party, that he predicted would soon flatten and ultimately reverse B.C.’s rising emissions trend. Those include:

- A “low carbon fuel standard” to cut the carbon content of B.C.’s fuel supply, which Heyman claimed to be North America’s most stringent.

- Rebates for zero-emissions vehicles and a ban on new gasoline and diesel cars after 2040.

- A mandated 45 percent cut in methane emissions from oil and gas production by 2025 (relative to the 2014 level).

Bridging the gap between B.C.’s existing mandates and its 2030 target will be easier than expected if Prime Minister Trudeau makes good on recently announced plans to ratchet up Canada’s nationwide carbon tax requirements. Starting in 2023, when releasing a ton of carbon dioxide should already cost polluters $39.4, Trudeau promises to begin adding $11.8 a year to reach $134 per ton in 2030.

Heyman estimated that Trudeau’s carbon tax boost could close roughly half of B.C.’s emissions gap. Modeling by the Climate Solutions Council suggests that it could do it all. Assuming, that is, that Trudeau follows through, and that he fends off attacks from Canada’s Conservative Party, which opposes the carbon tax.

Calling all activists

Mazza, Gruen and other activists say only increased public support can conjure and sustain the political will required for the climate action turnaround that’s needed across Cascadia.

One of the most active grassroots groups fighting climate change in Cascadia has been 350 Seattle. Here, the organization’s board president, Patrick Mazza, is arrested in September 2019 during the group’s protests against Chase Bank. 350 Seattle via Twitter

Mazza joined activist group 350 Seattle and returned to direct action in 2014, when he was arrested blocking an oil train in Everett, Washington, as part of the Thin Green Line movement. And in 2019 a then-66-year-old Mazza got himself arrested again disrupting a Chase Bank branch to shine a light on the financing behind fossil fuel developments. 350 Seattle’s Chase campaign spread across the U.S., and the bank recently said it intends to align its lending practices with the 2015 Paris Agreement on climate change.

Producing that kind of change is why Mazza calls getting hauled off to jail “the most valuable thing I can do today.”

This year, however, he said Cascadia’s politicians need to hear a more positive message to move them forward amidst the ongoing pandemic and looming budget crises that could stall climate action. “’Kill fossil fuels’ is a negative. We need a positive. Look at how many people are unemployed right now. Whatever we do has to have a huge jobs message,” said Mazza.

For Gruen the positive message du jour to deliver decarbonization in Cascadia centers on justice, and on economic development that stresses sustainability over consumption. As Gruen put it, “Solving the climate crisis is not just about switching fuels and changing technologies. It’s about how we sustain a healthy economy and healthy communities.”

What has Quigley feeling optimistic again is how much has changed since a decade ago. Not just cheaper solar panels and heat pumps and growing knowledge about how to incentivize their growth, but also in public opinion. Last year’s wildfires and other impacts show the hour for cutting greenhouse gases is late. As Quigley puts it: “We obviously are way up against the clock.”

But such climate impacts have also fostered widespread awareness that climate change is a crisis that must be confronted. Quigley said broadly shared awareness, plus improvements in technology, put Cascadia in a “very hopeful” position in 2021.

As she puts it: “We are really primed to move.”

Getting to Zero: Decarbonizing Cascadia explores the path to low-carbon energy for Washington, Oregon, and British Columbia. All rely heavily on hydropower, are transitioning from resource extraction industries, have rapidly diversifying populations and face common challenges as they transition off fossil fuels. This story was supported in part by the Fund for Investigative Journalism.