This article was published in partnership with The Marshall Project, a nonprofit news organization covering the U.S. criminal justice system. Sign up for their newsletters here.

Additional reporting by Geoff Hing.

Illustrations and reporting by Susie Cagle. Cagle is a 2023 Alicia Patterson Foundation journalism fellow.

Citations

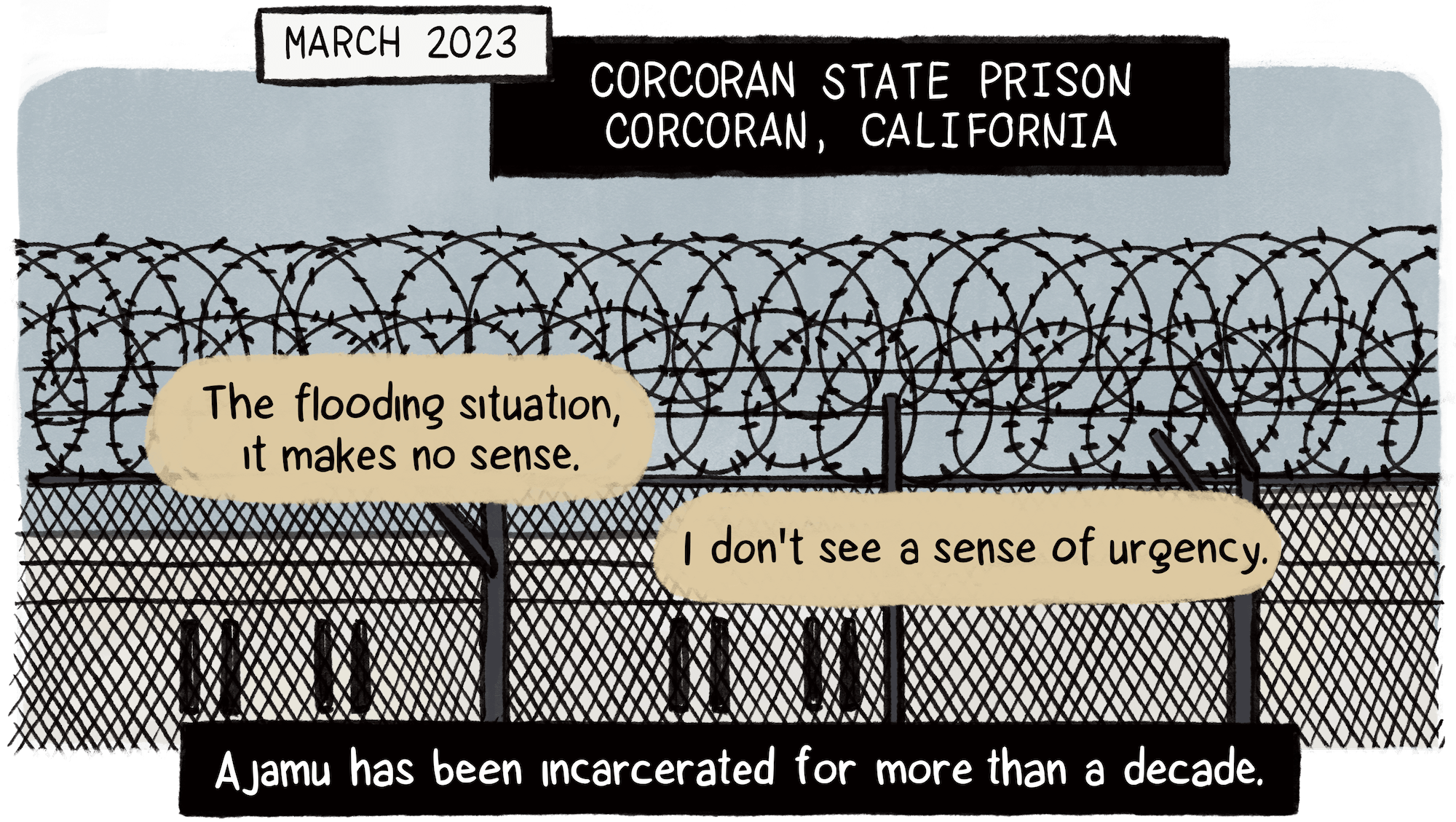

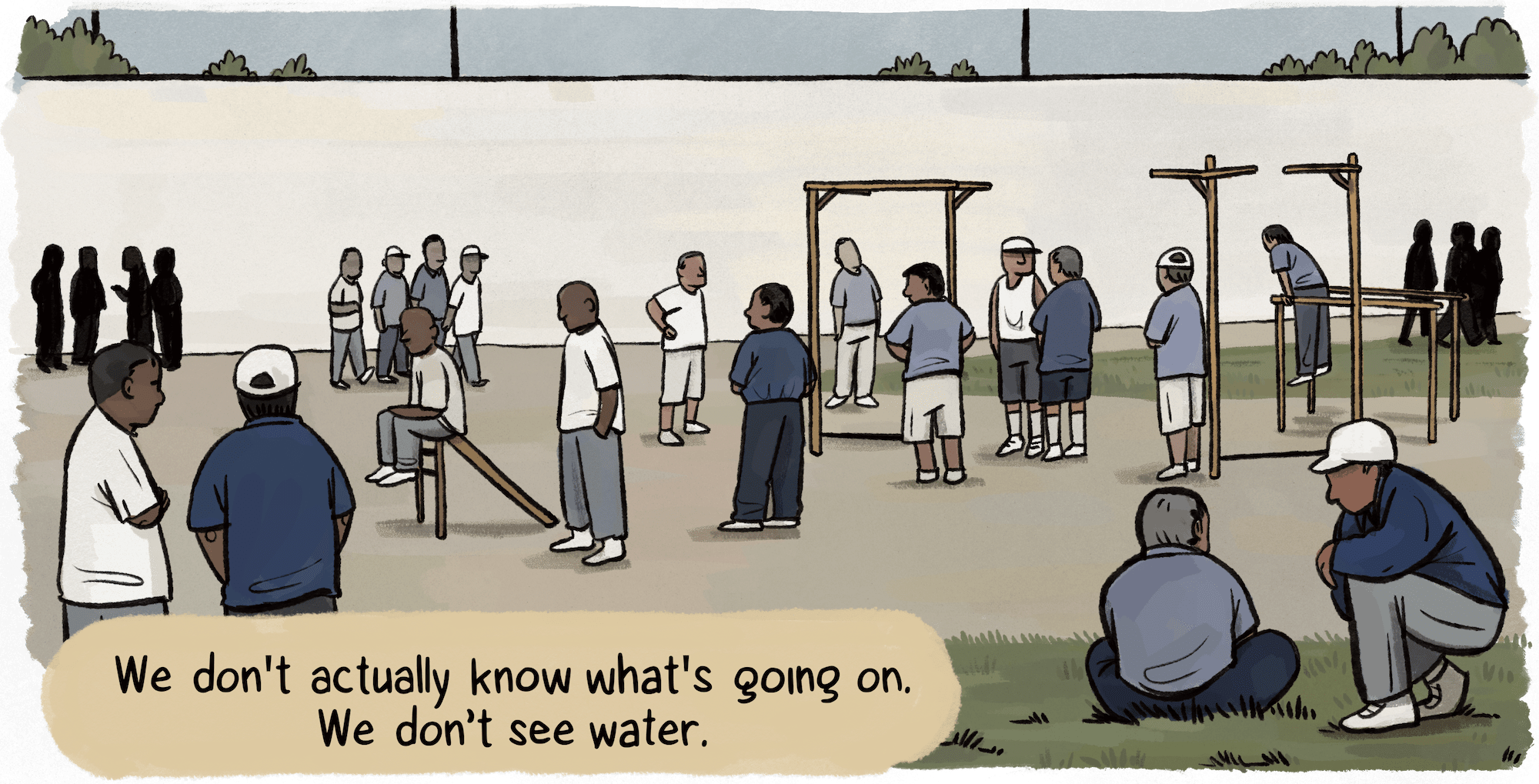

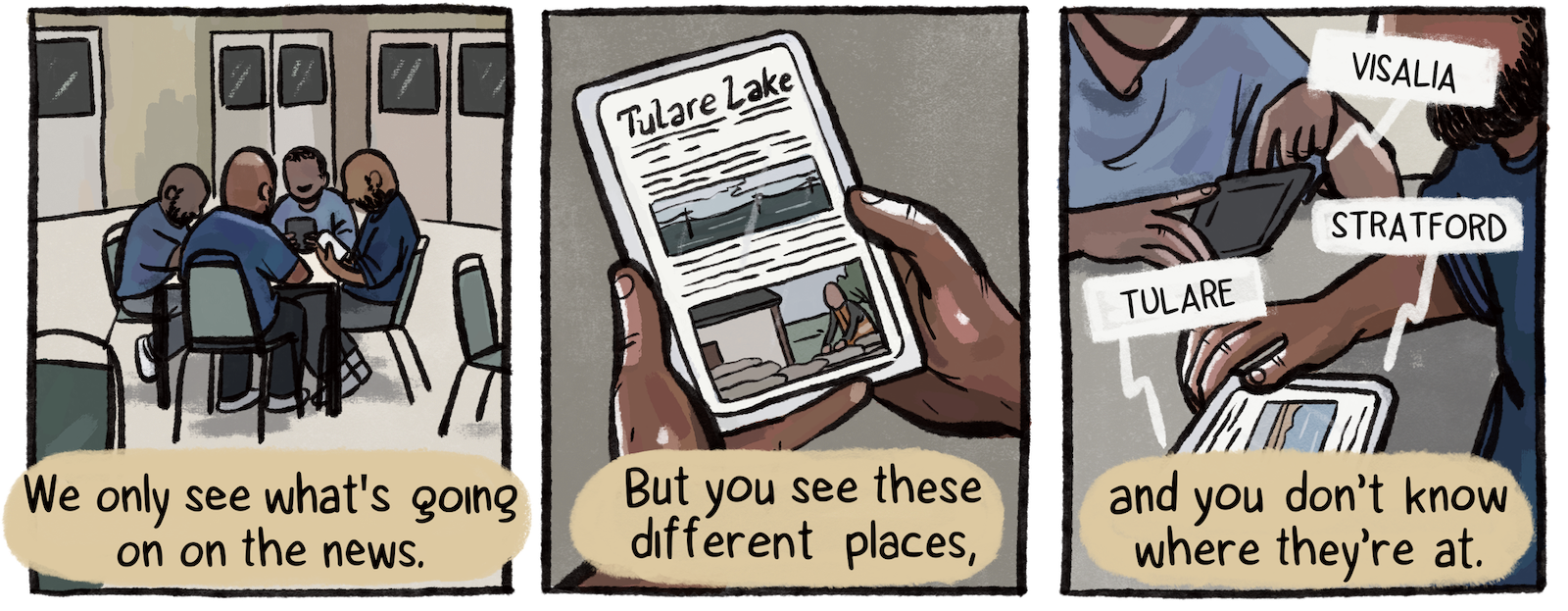

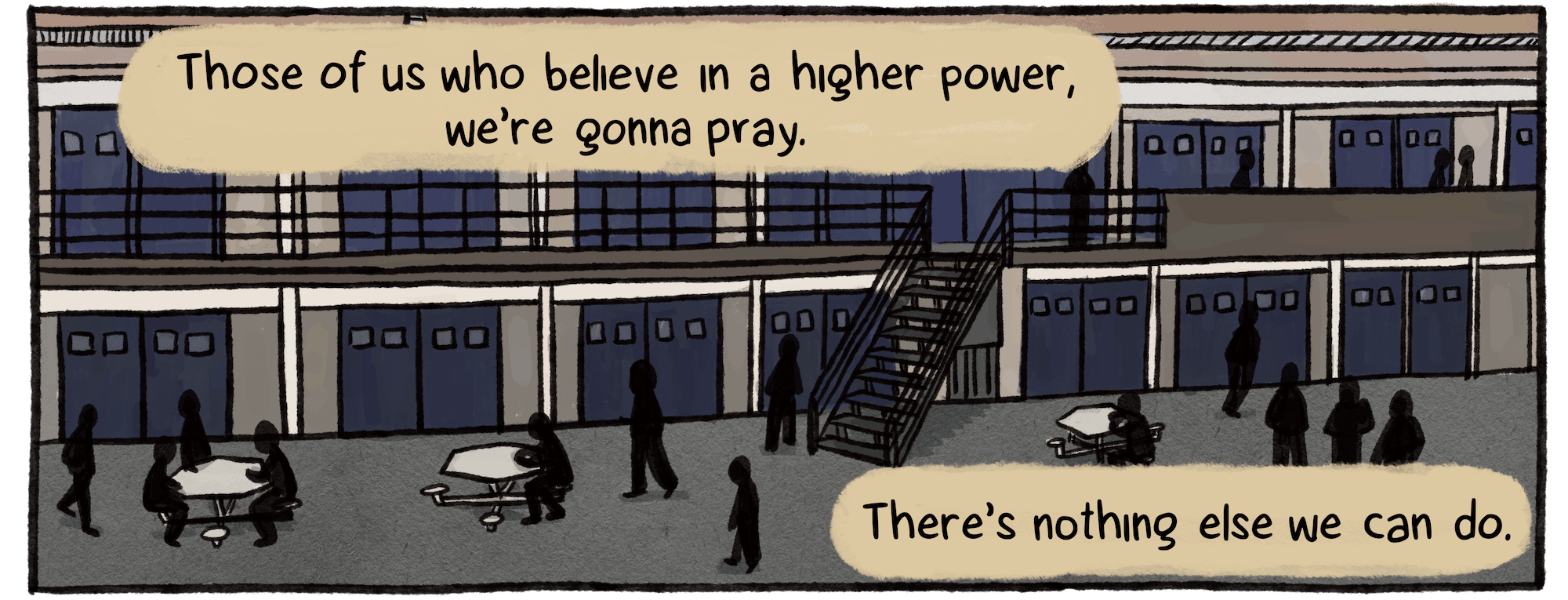

Ajamu spoke with TMP on the condition that his nickname, “Ajamu,” be used to identify him because he feared retribution for speaking out.

The landslide was stabilized by private contractors in the summer of 2022, but unprecedented flash flooding across eastern Kentucky on the morning of July 28 triggered the property’s second slide. While flooding is Kentucky’s most frequent and costly natural disaster, landslides — typically triggered by rainfall — follow close behind.

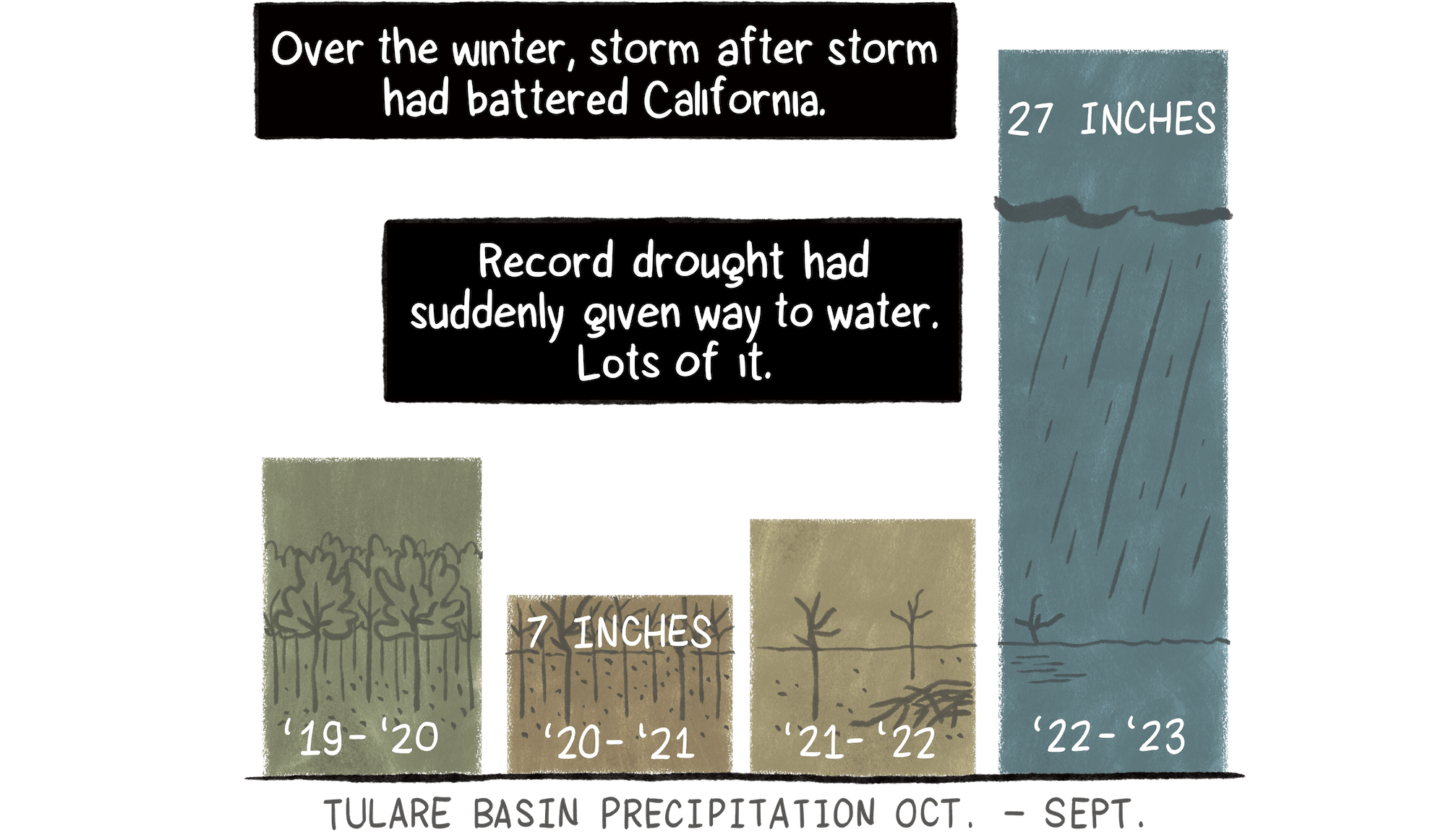

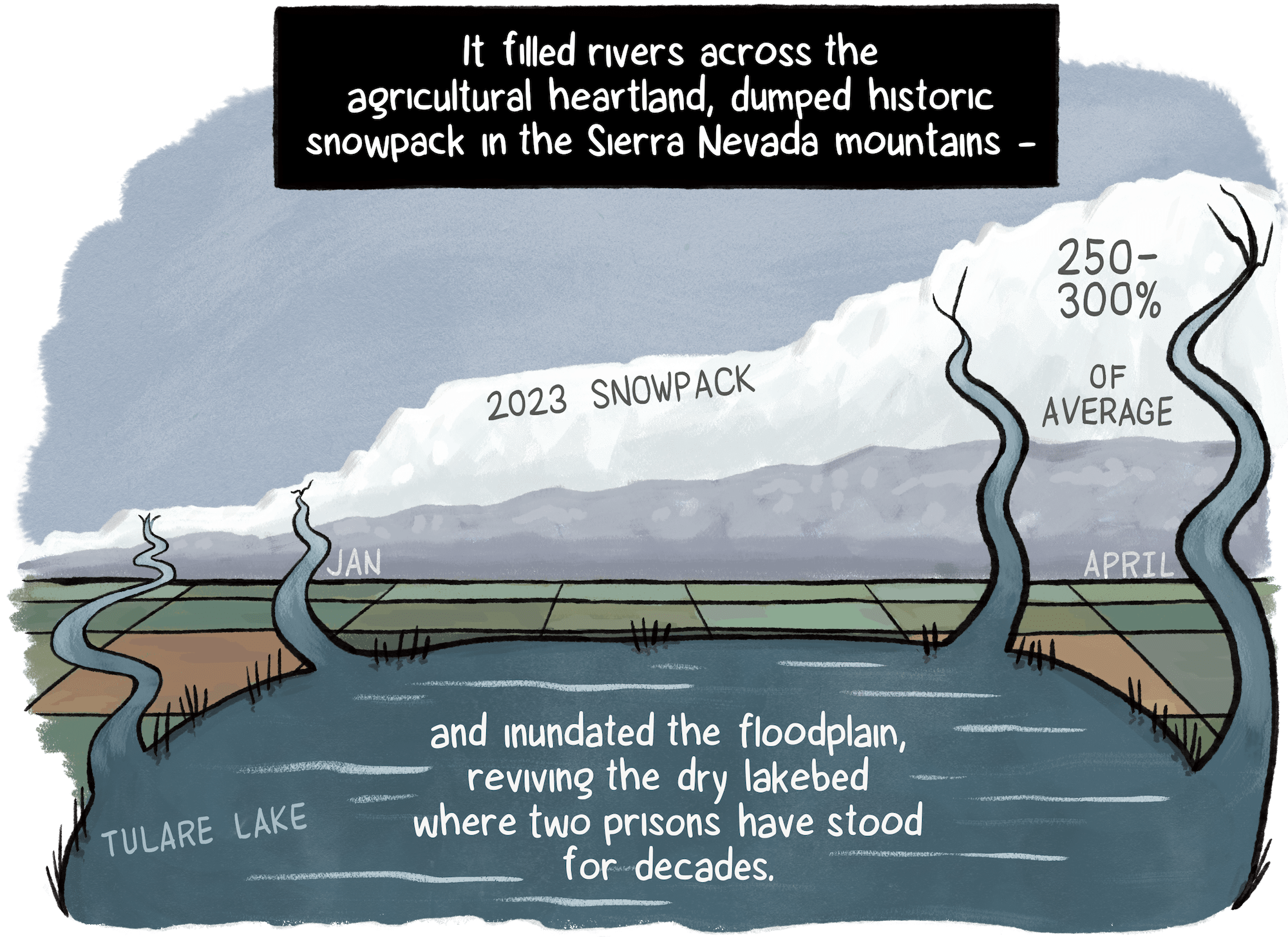

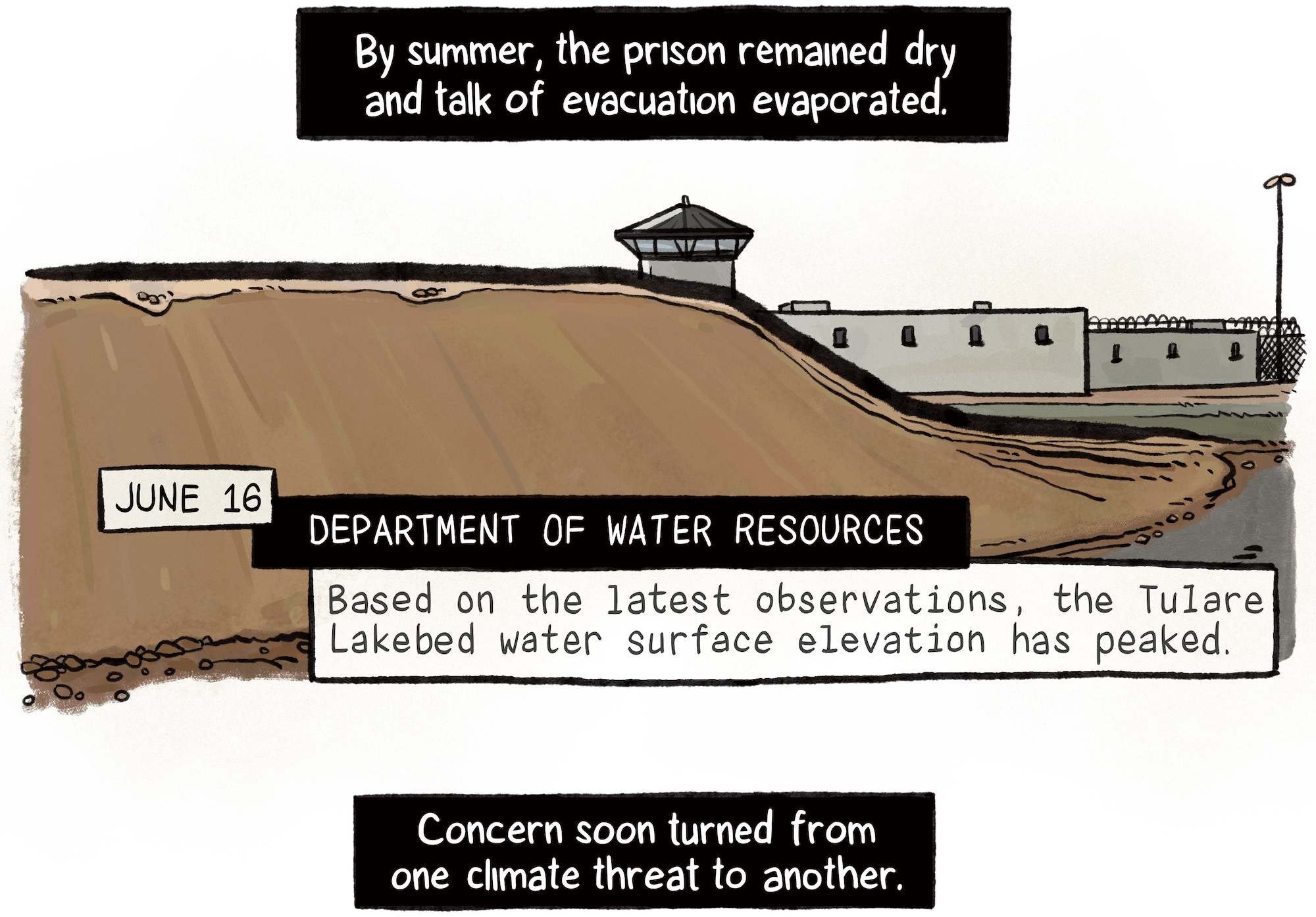

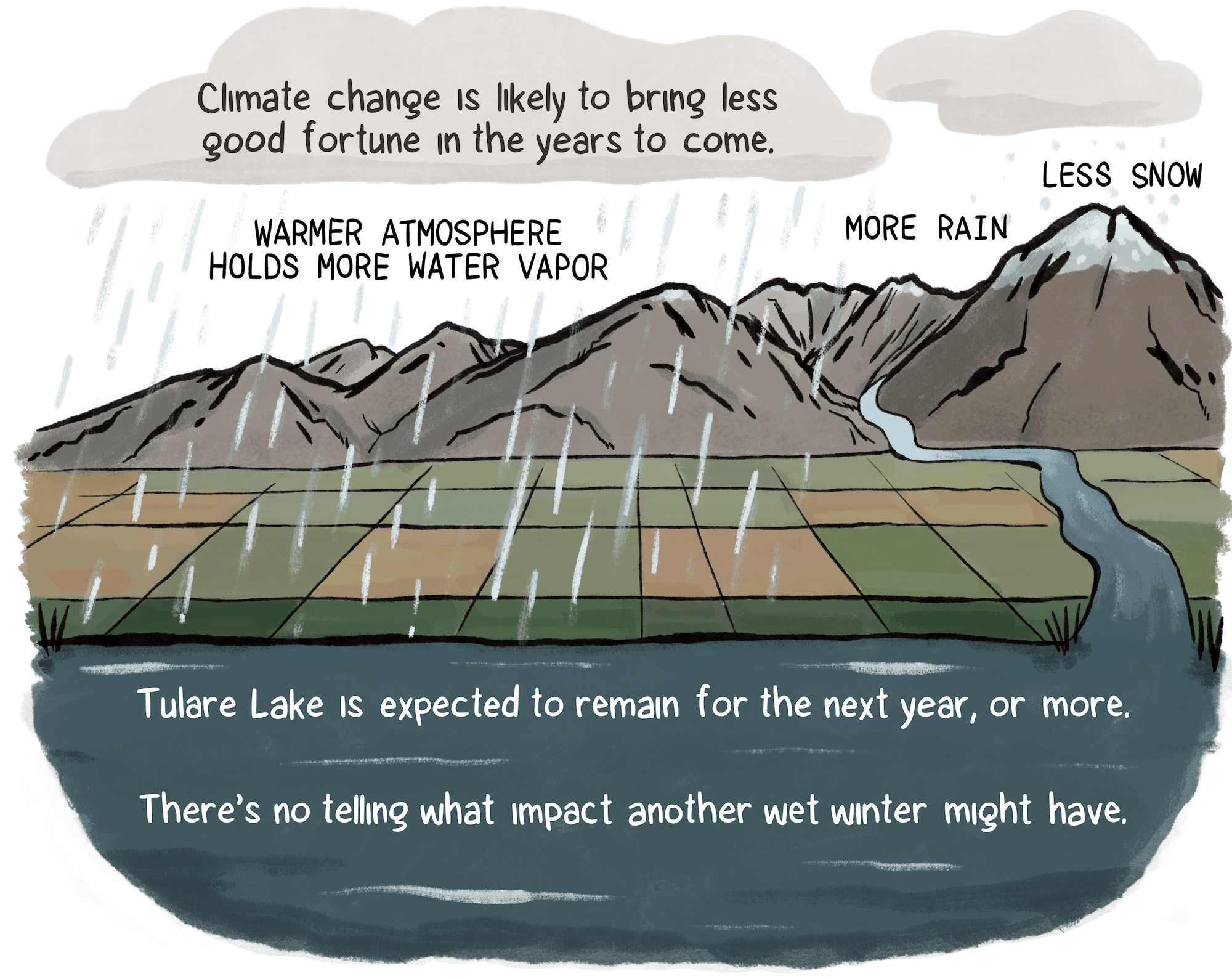

Precipitation and snowpack data from the California Department of Water Resources.

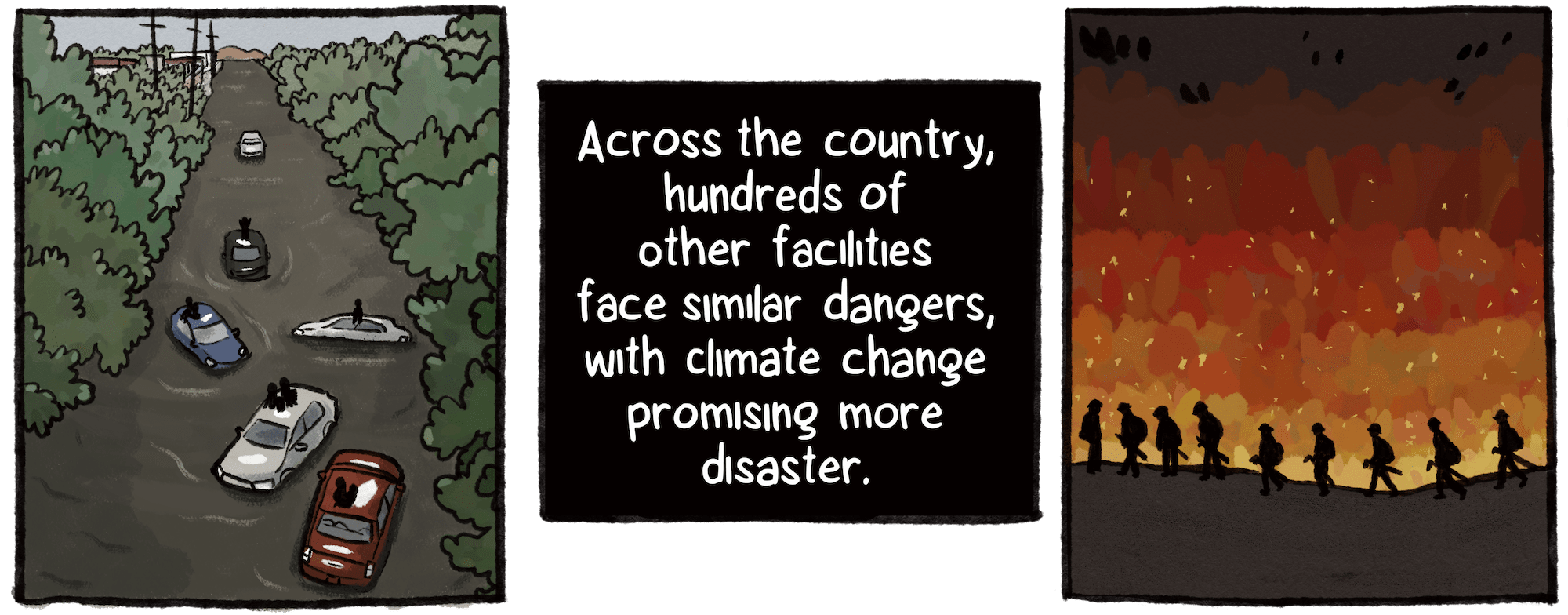

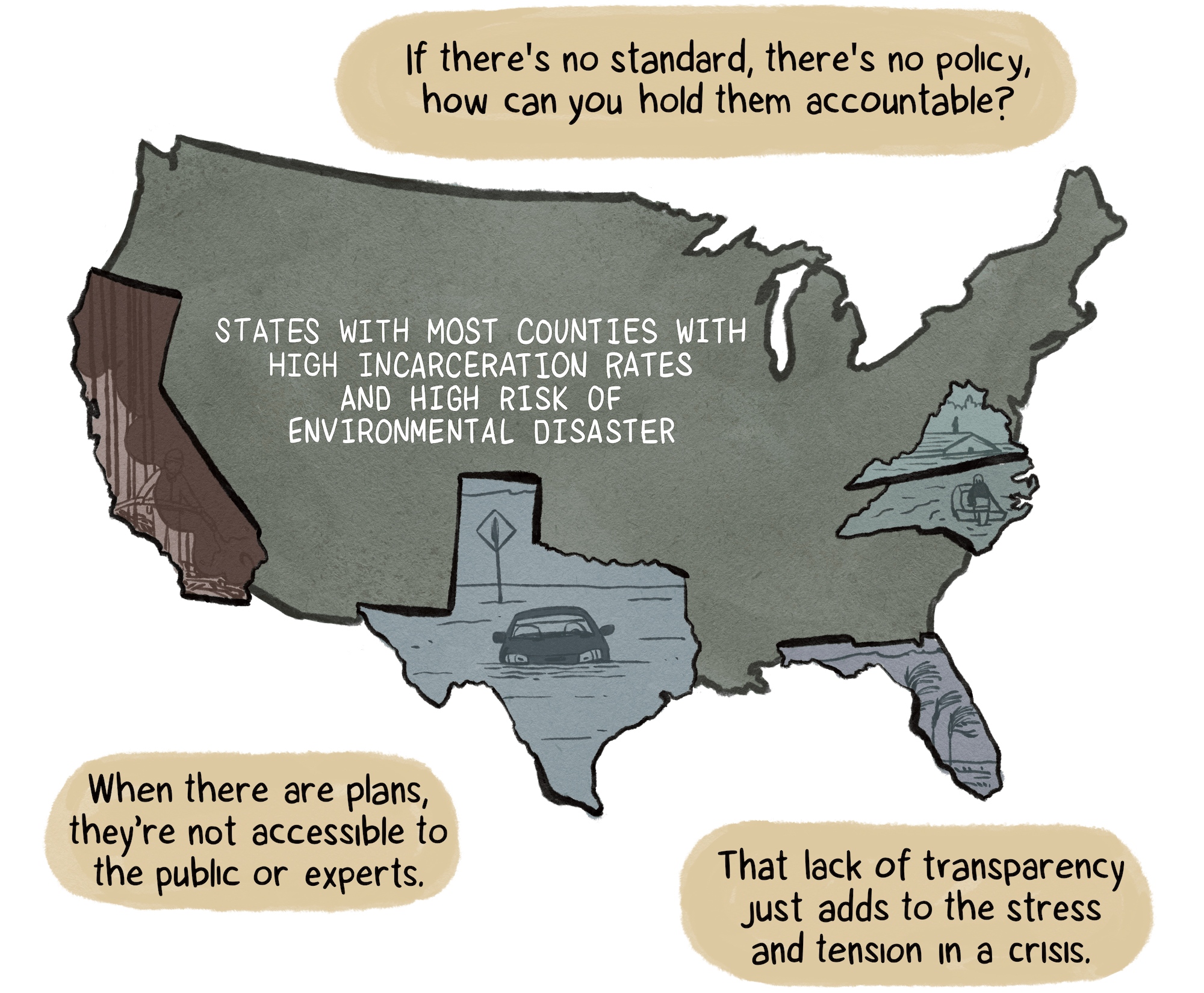

National analysis based on data from the Federal Emergency Management Agency and U.S. Census Bureau.

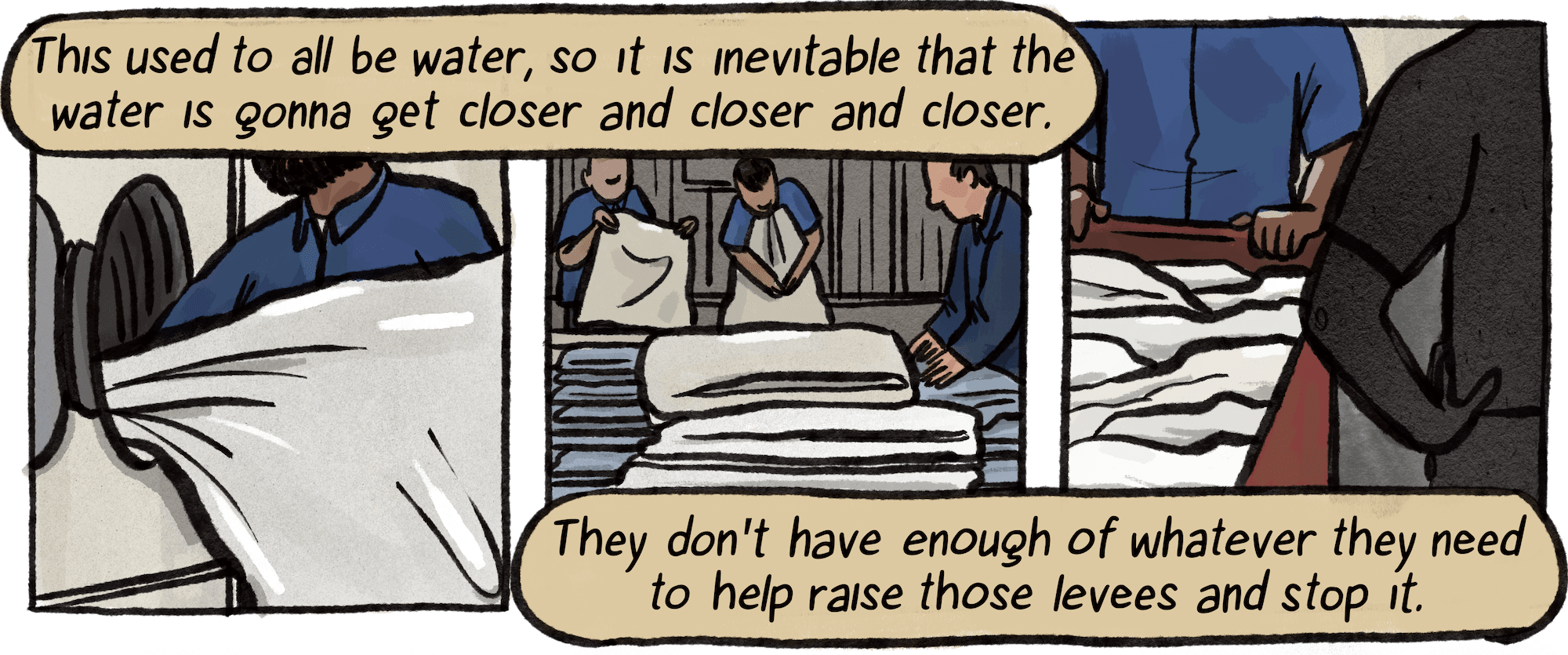

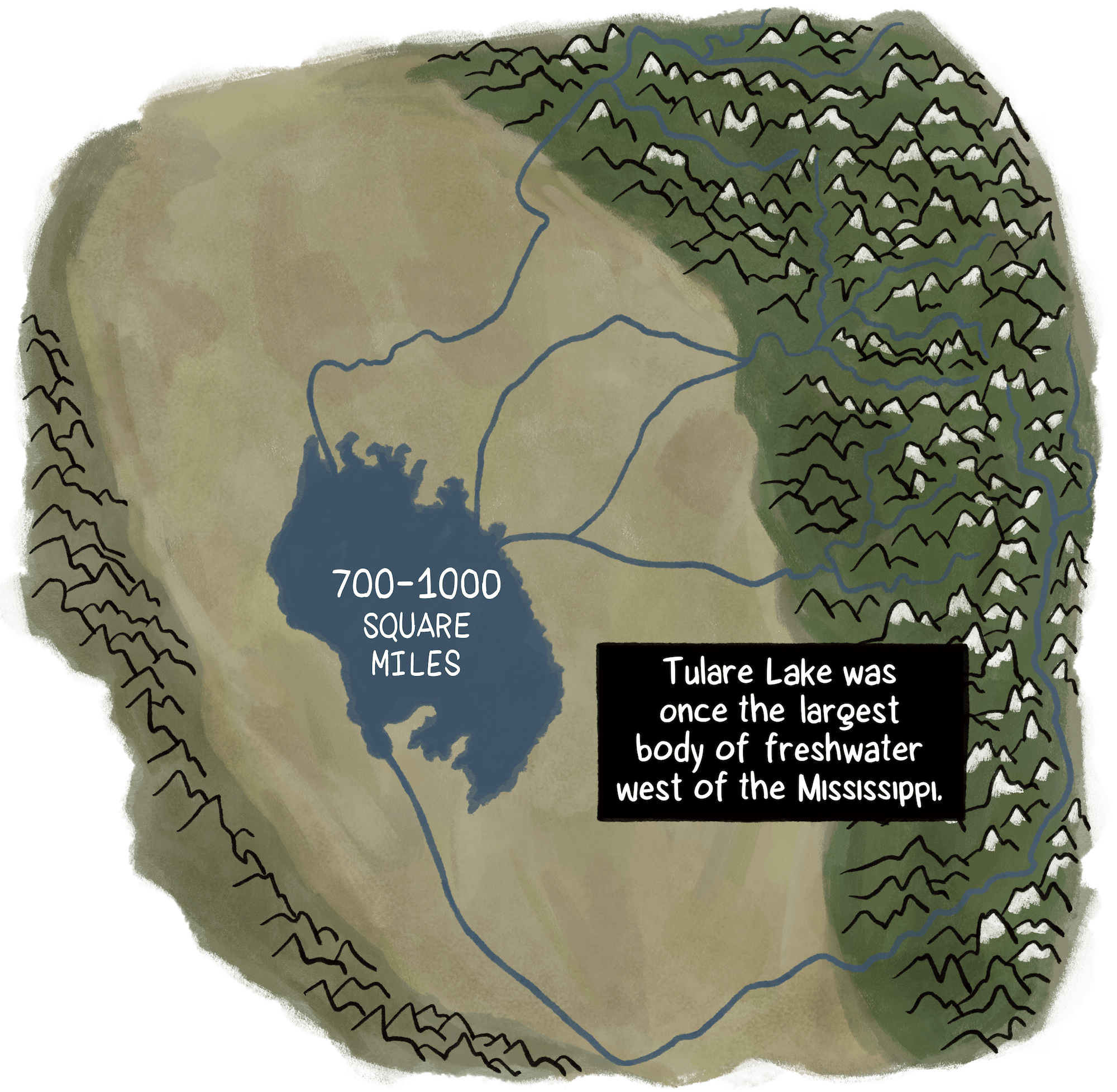

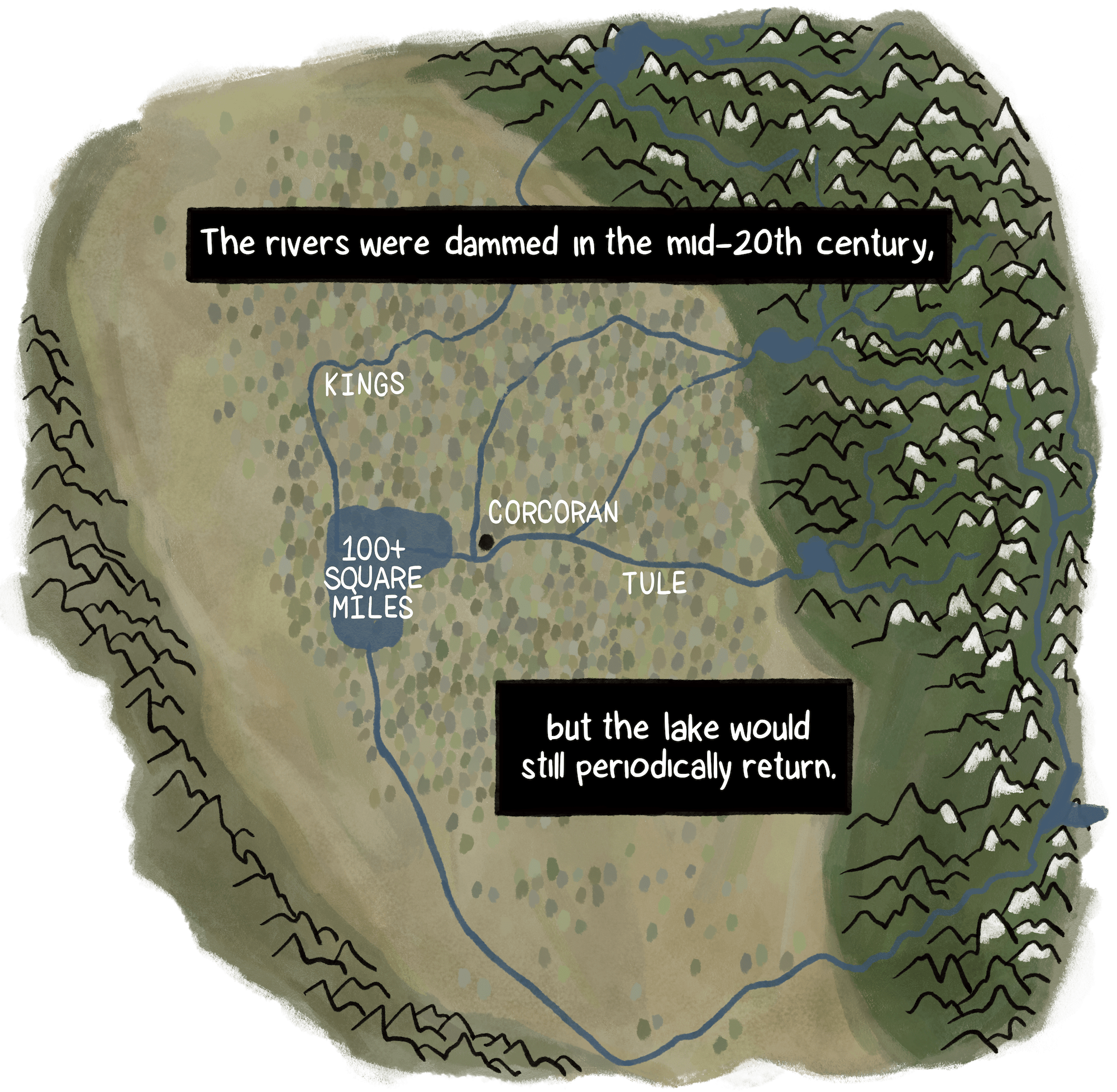

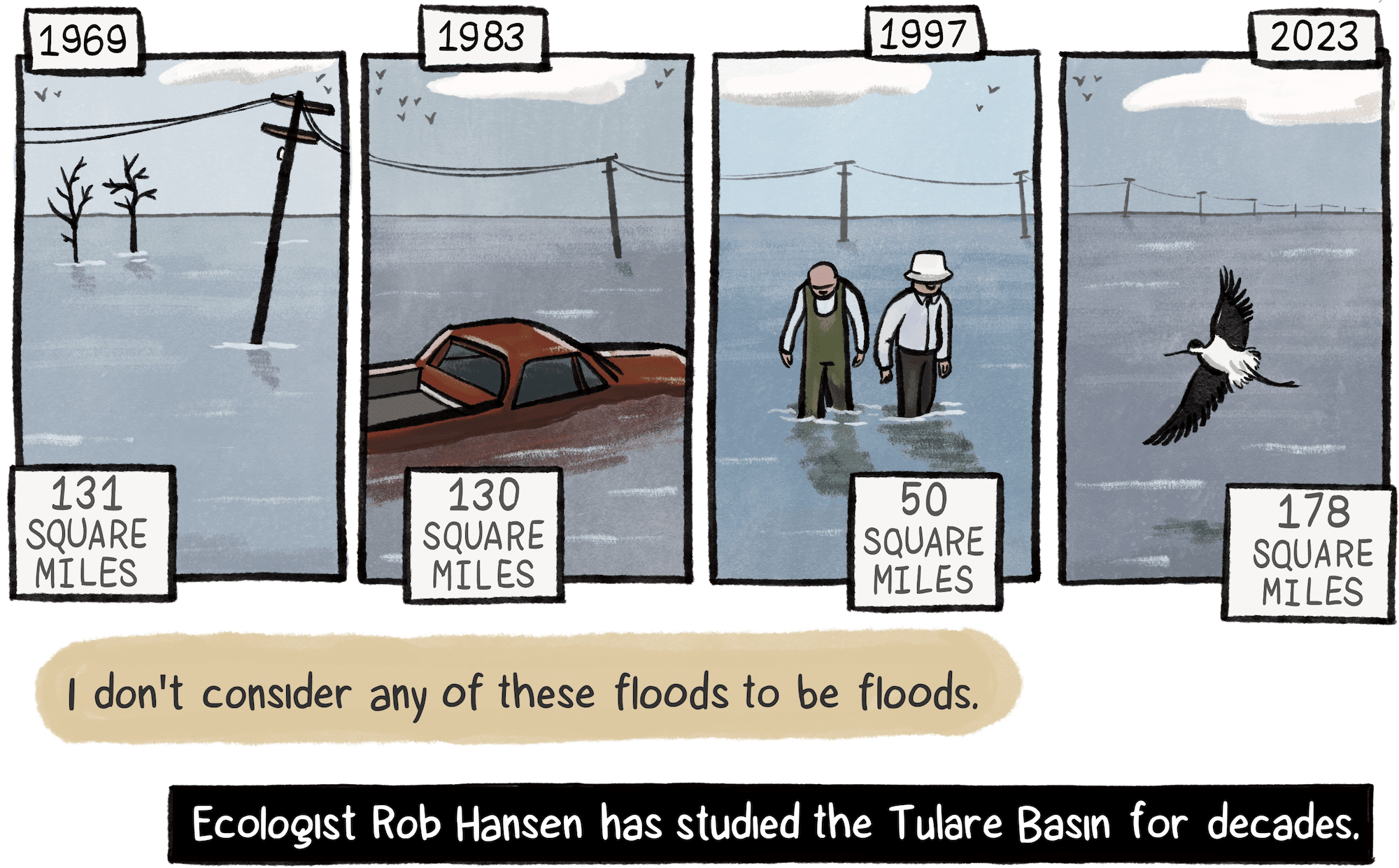

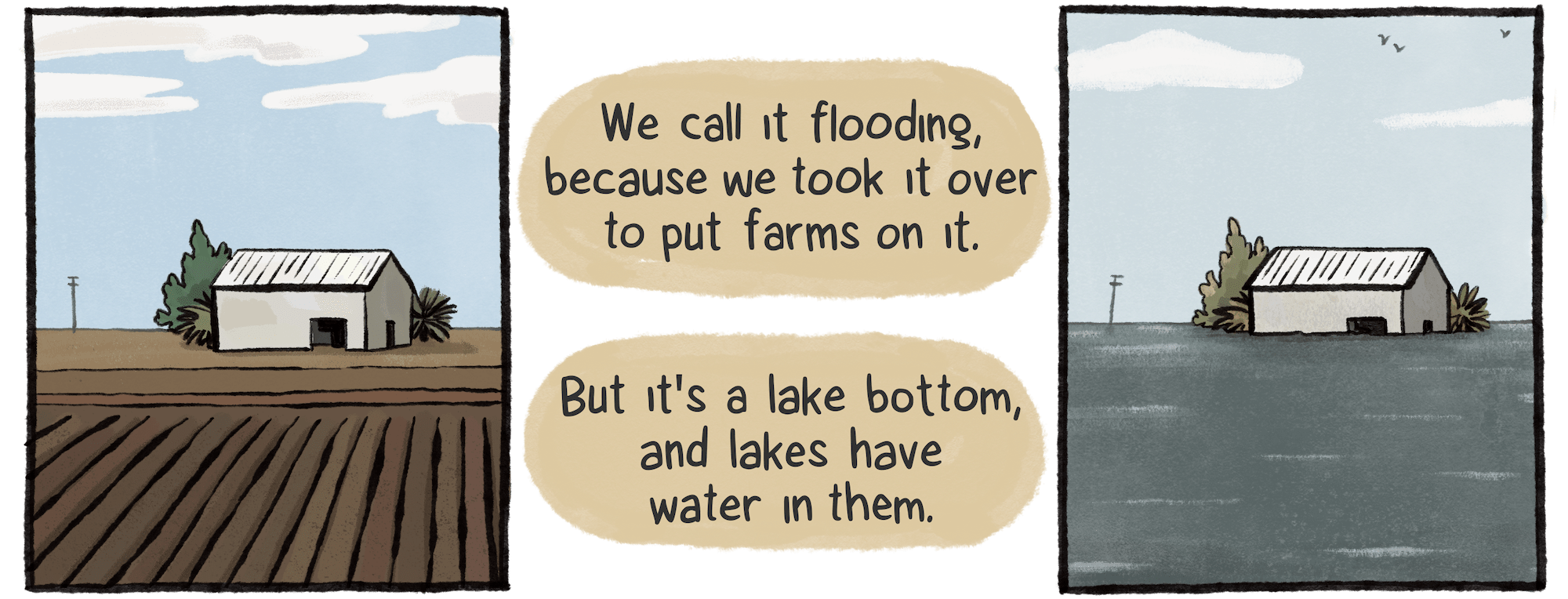

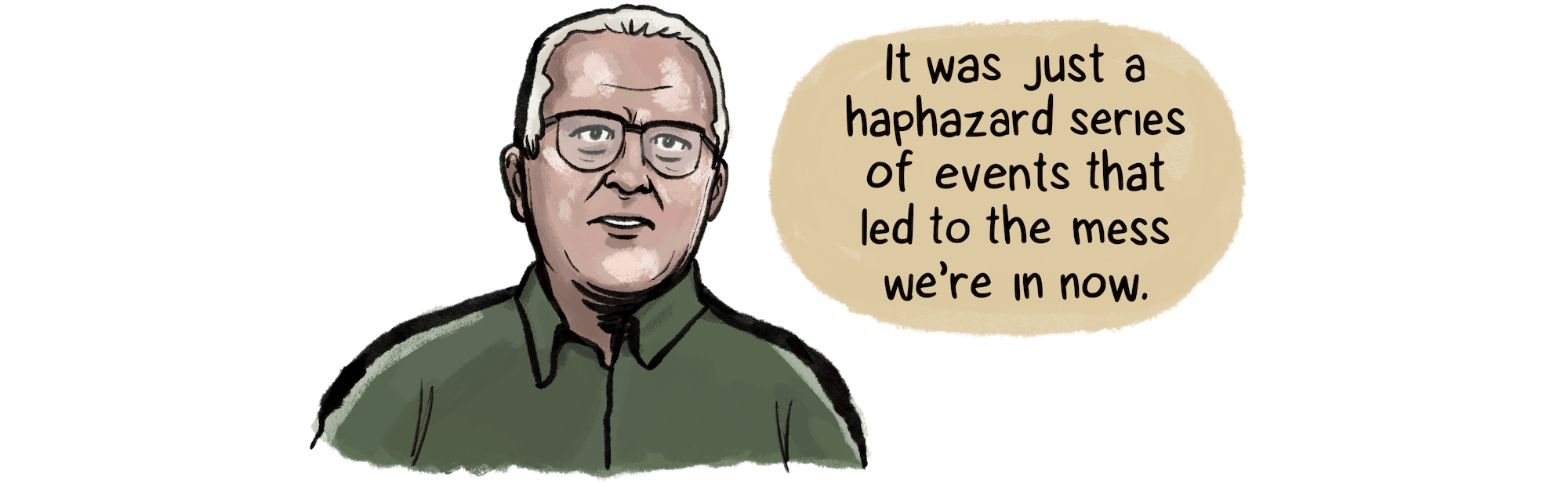

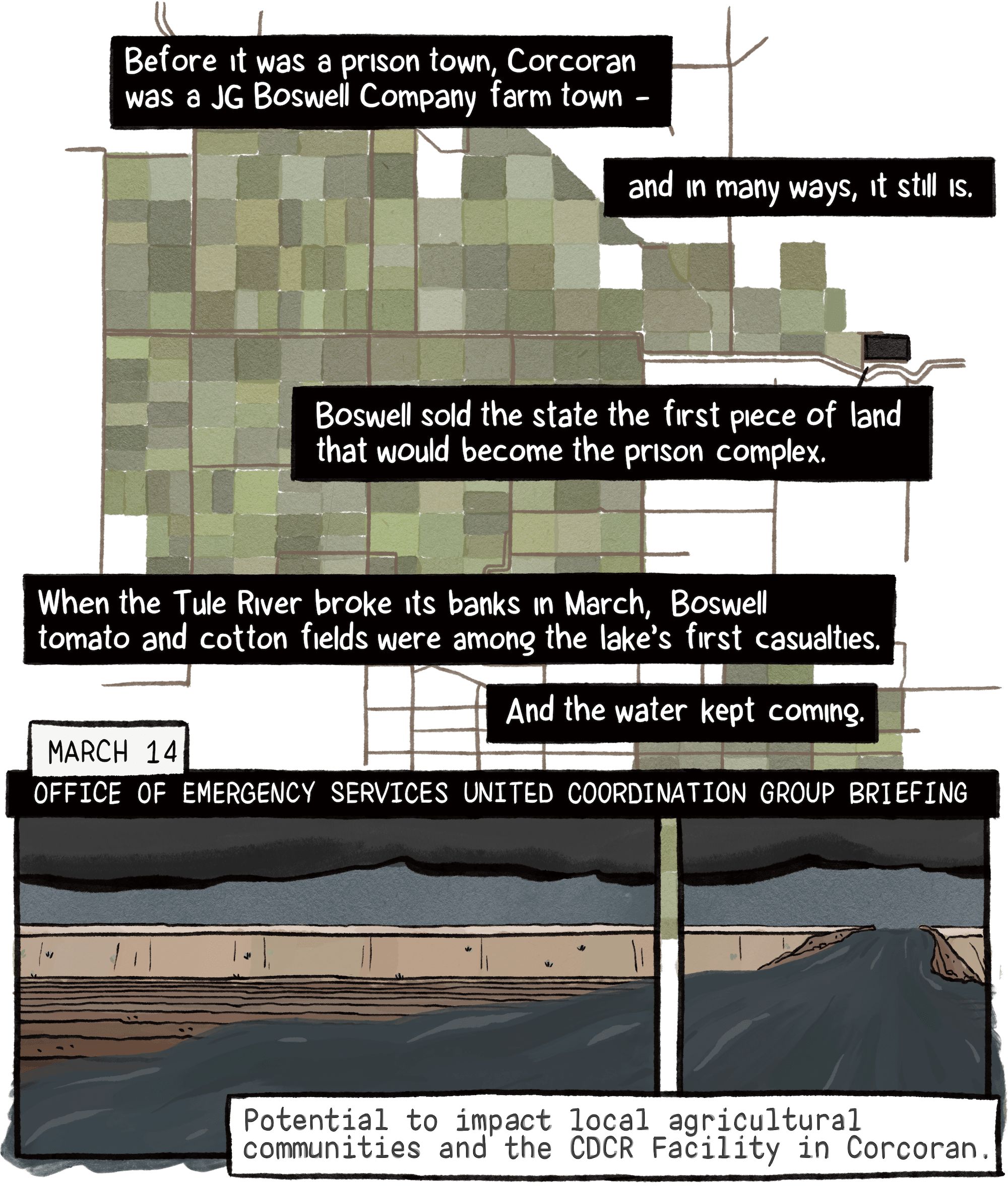

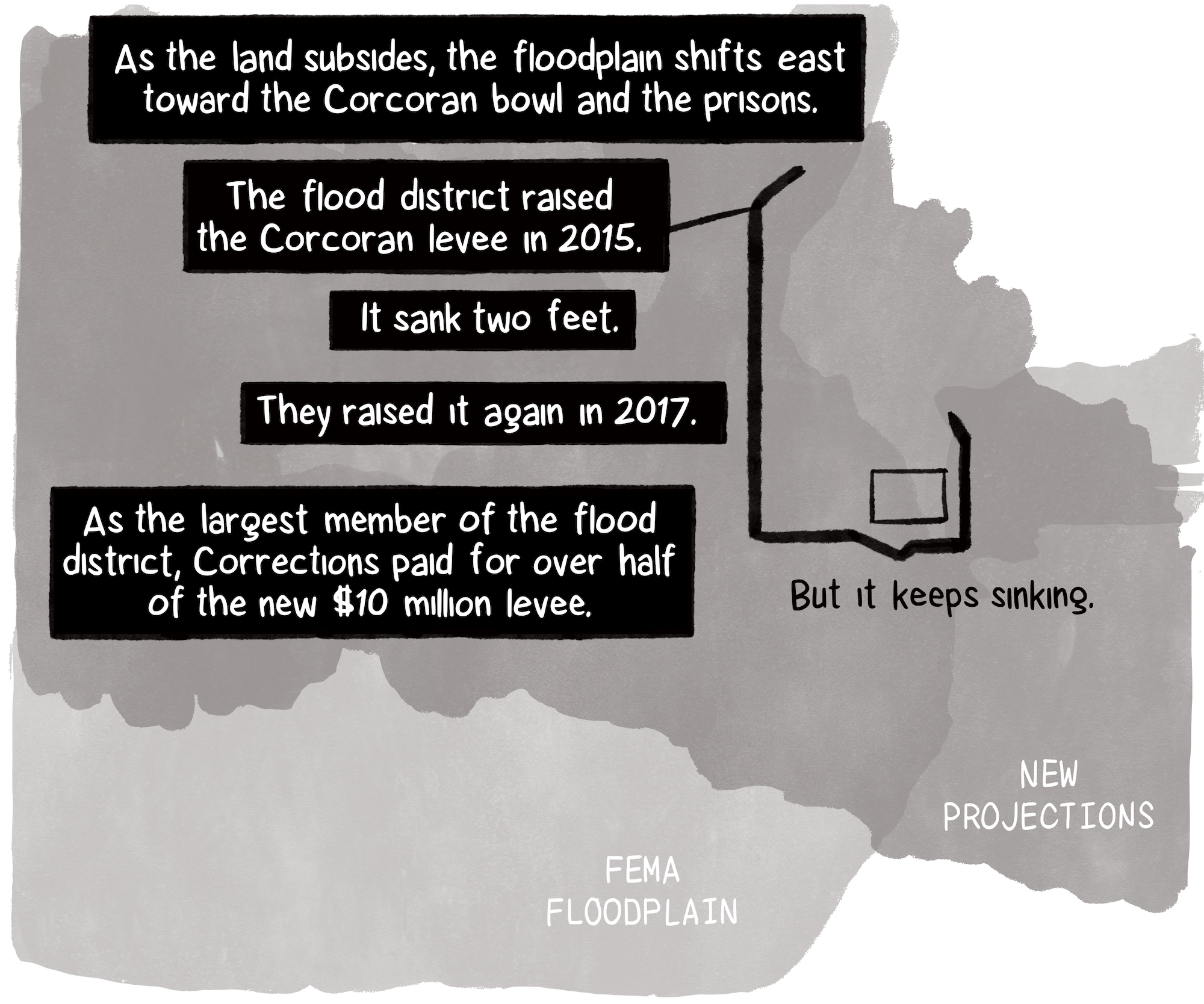

Floods and Droughts in the Tulare Lake Basin, by John T. Austin; Department of Water Resources.

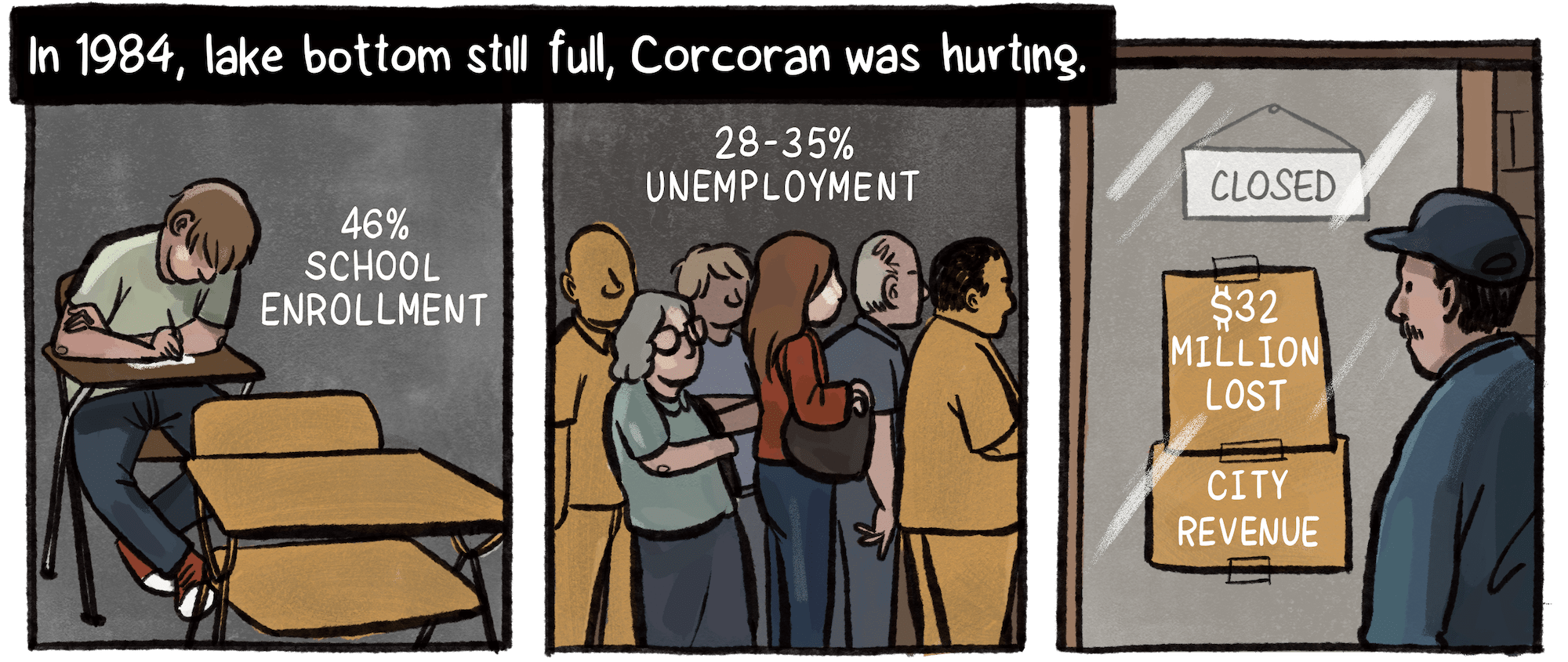

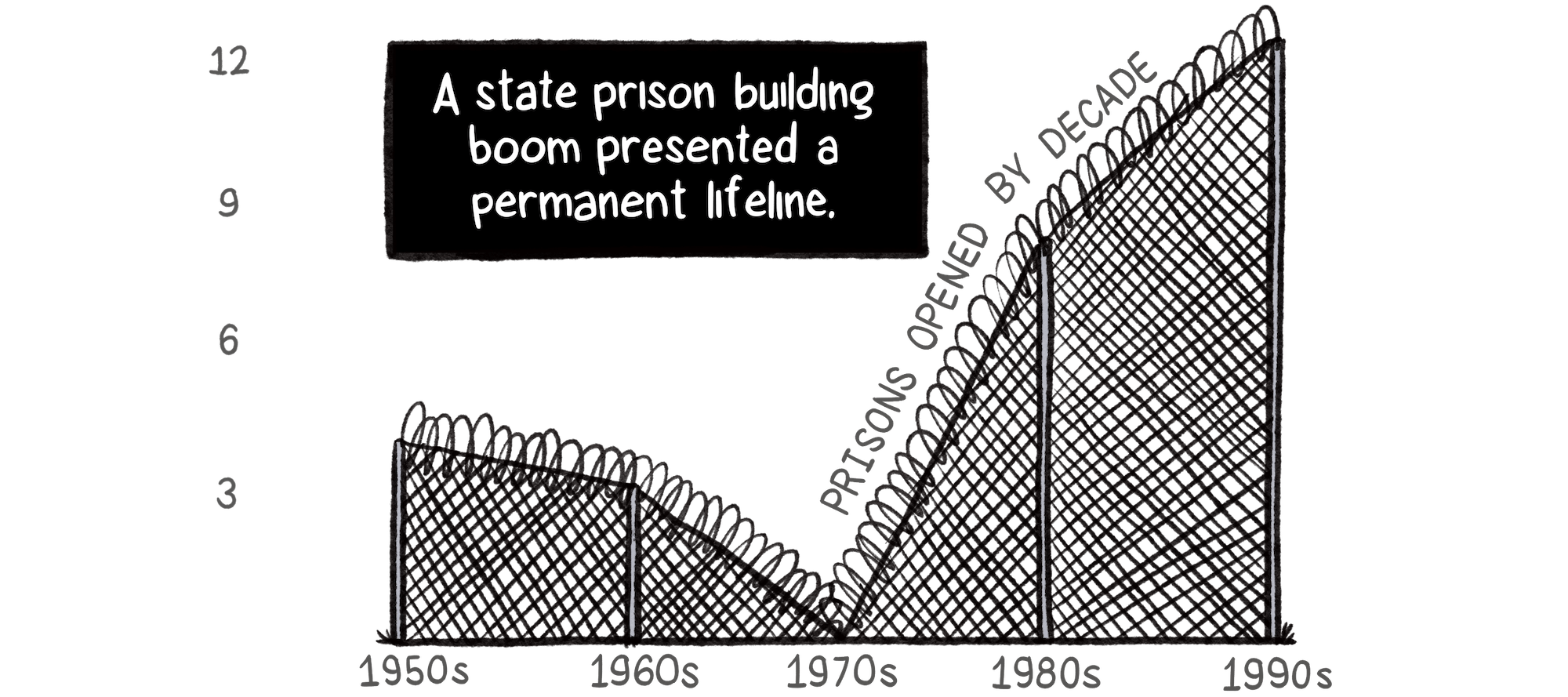

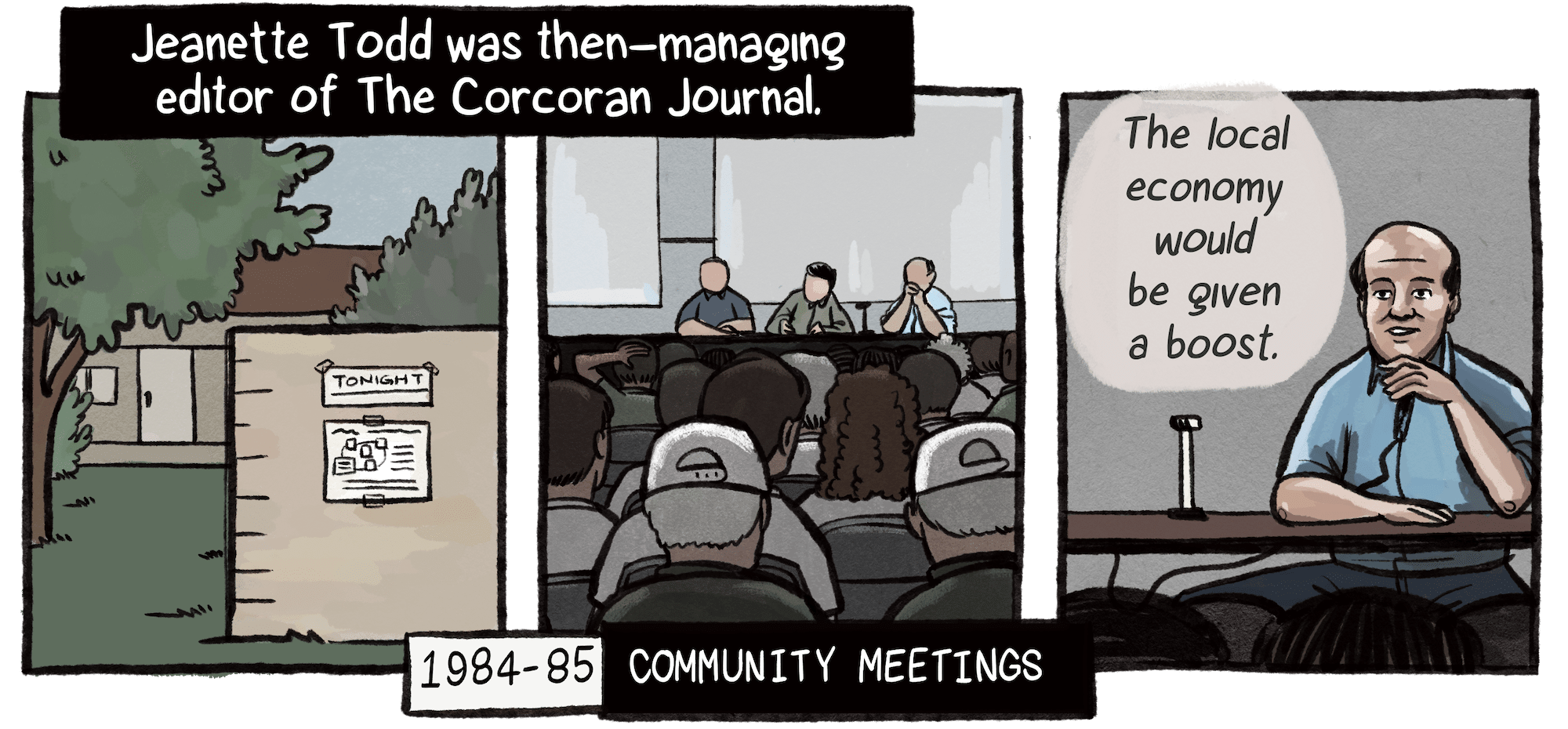

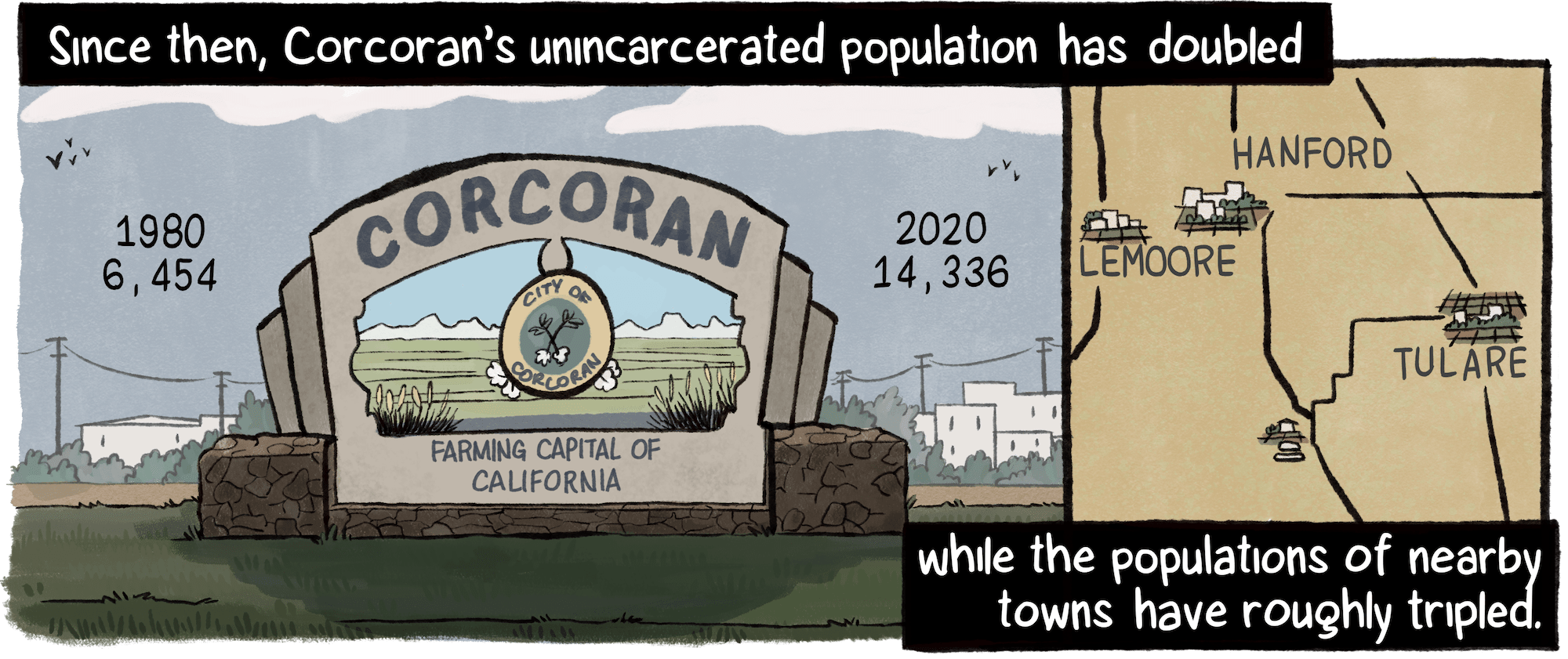

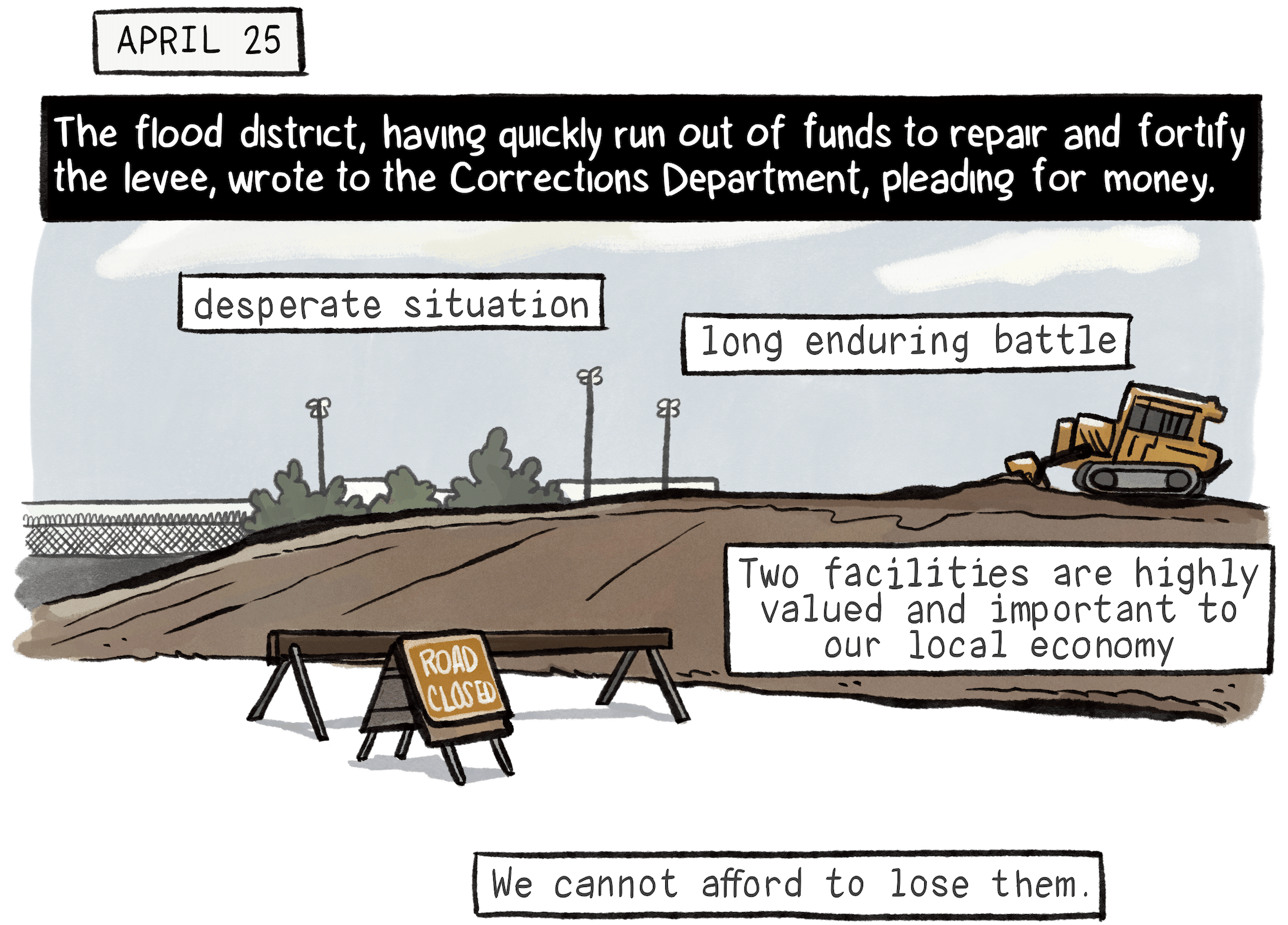

School enrollment data, Hanford Sentinel, October 17, 1984; unemployment and lost city revenue, April 26, 1986.

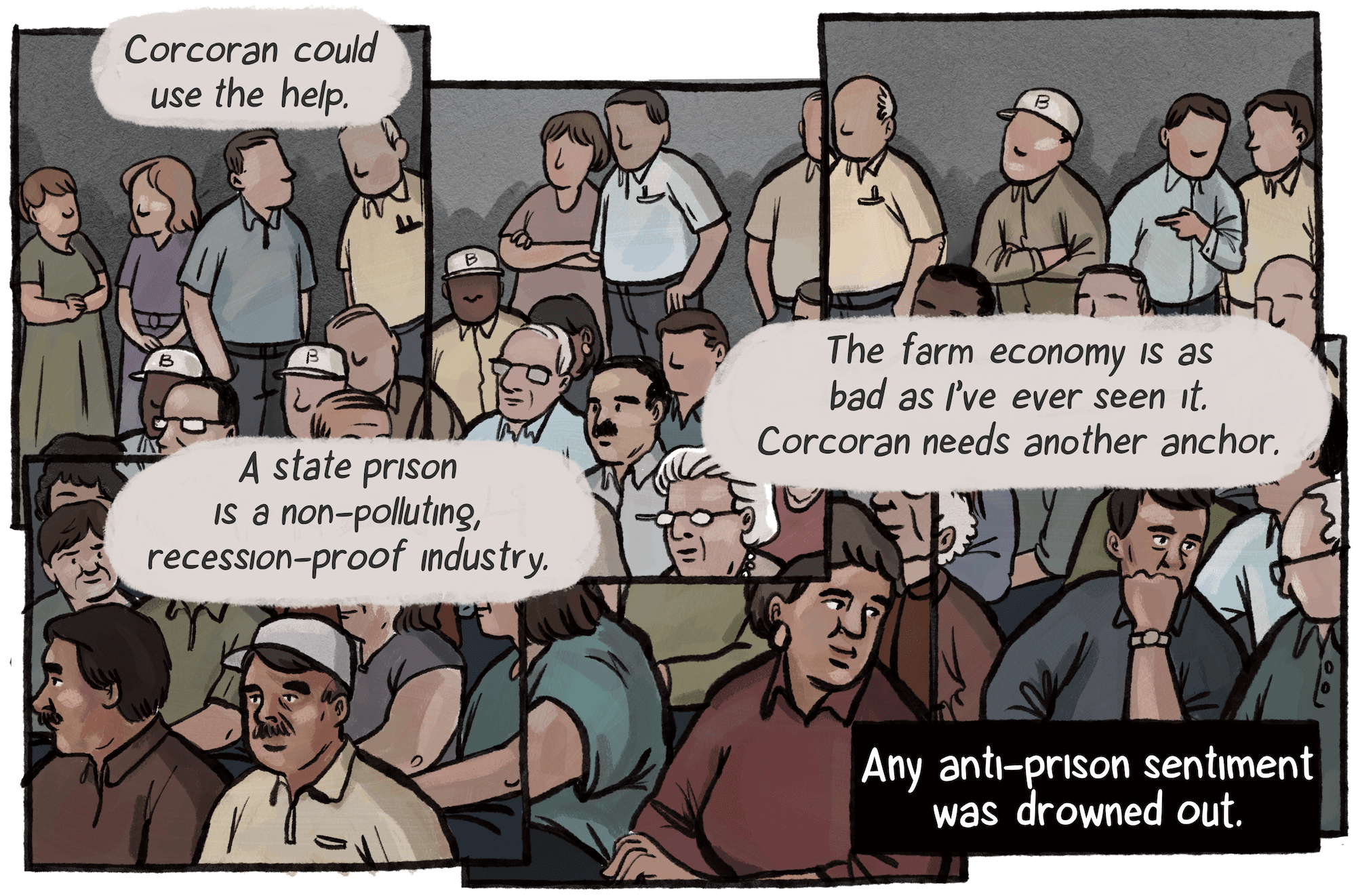

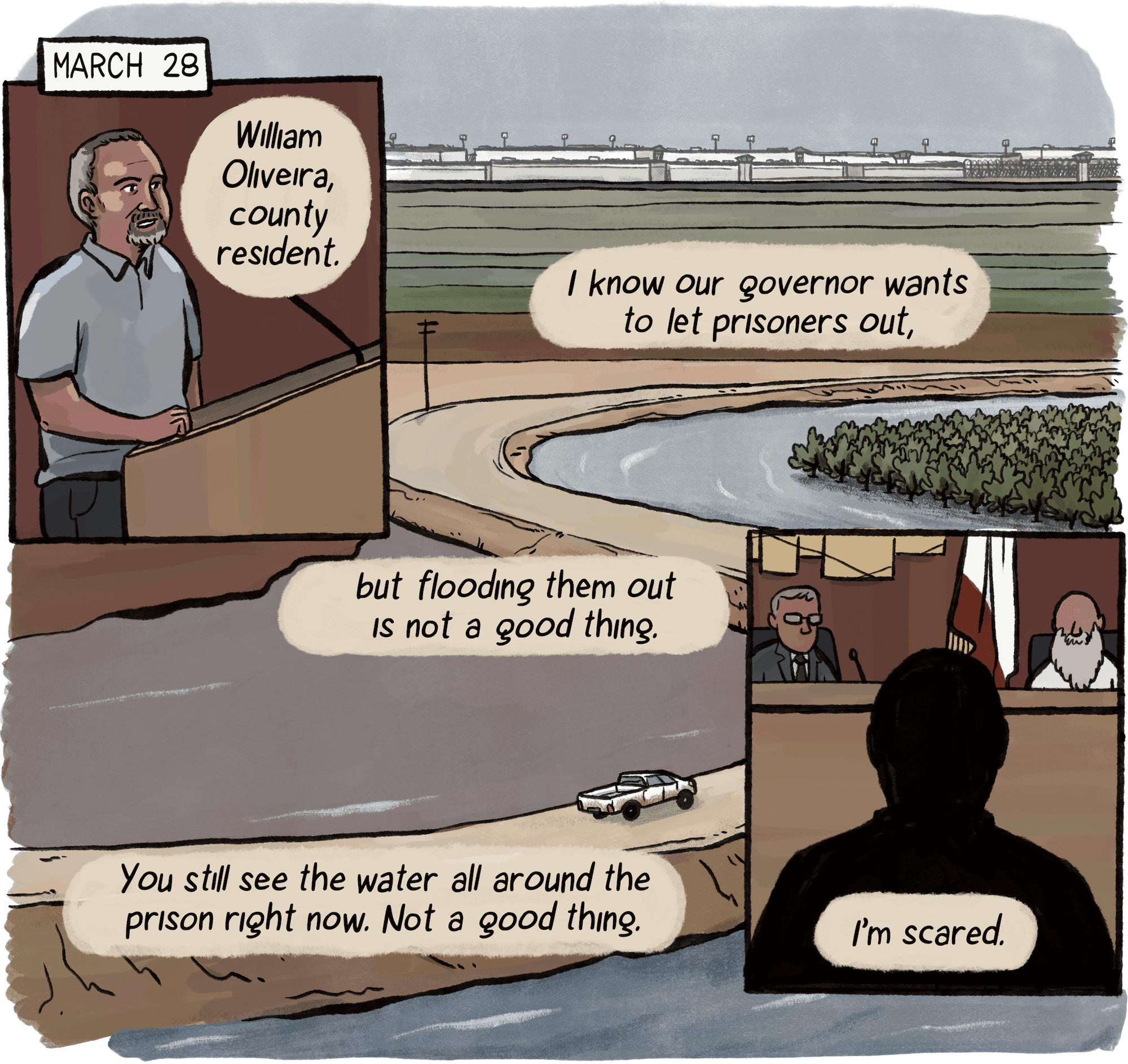

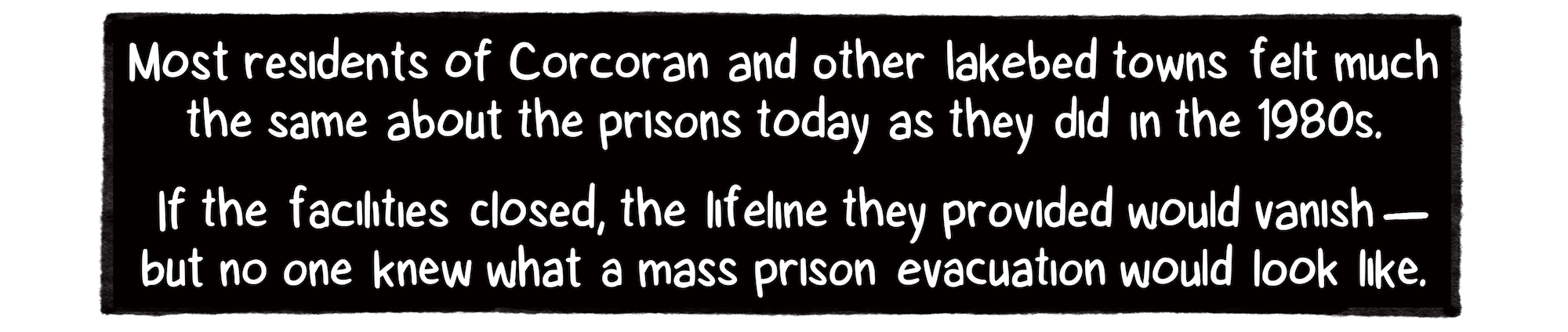

Residents and officials at local meetings were quoted in the Corcoran Journal and the Fresno Bee, from 1984 to 1986.

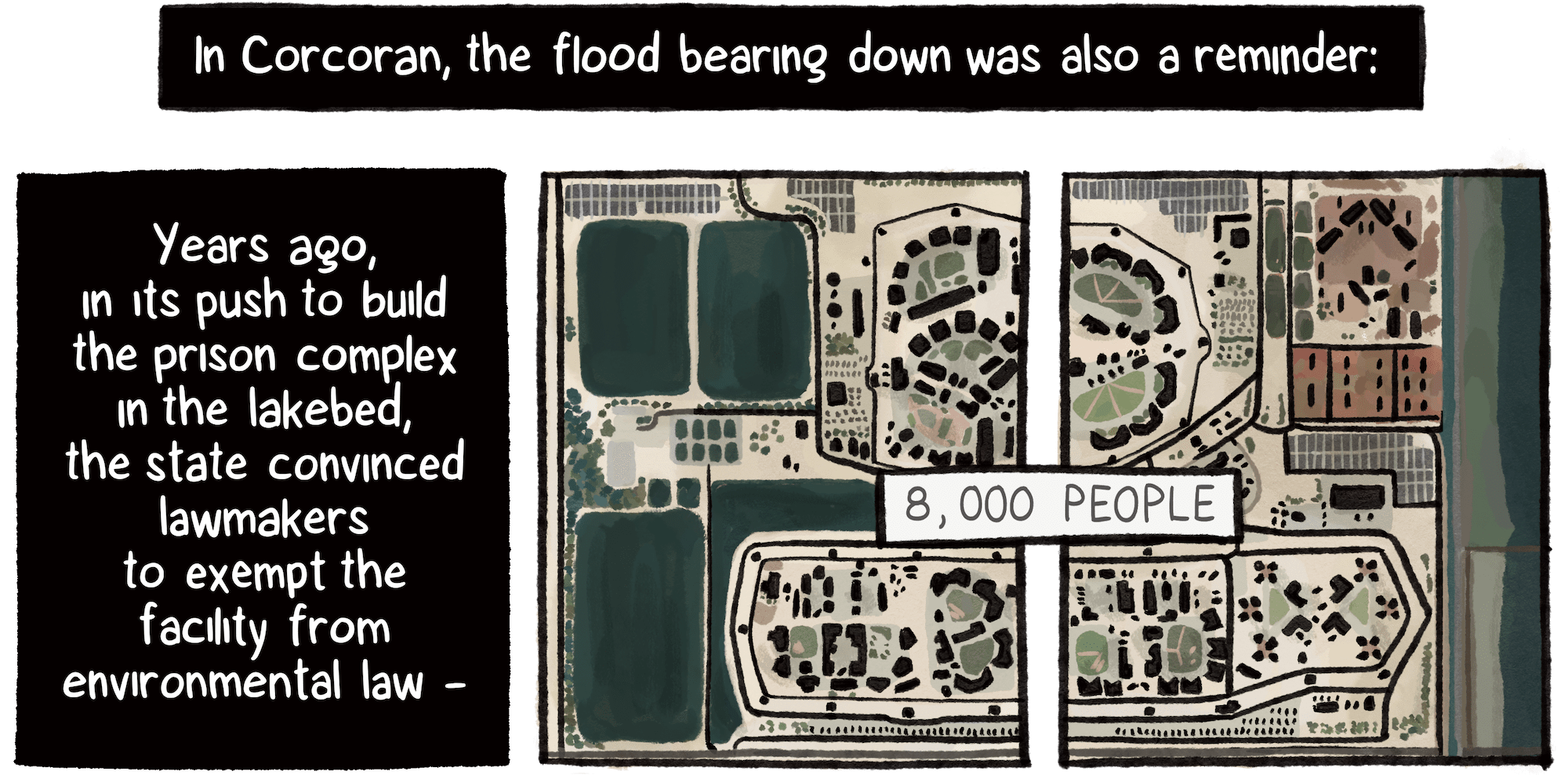

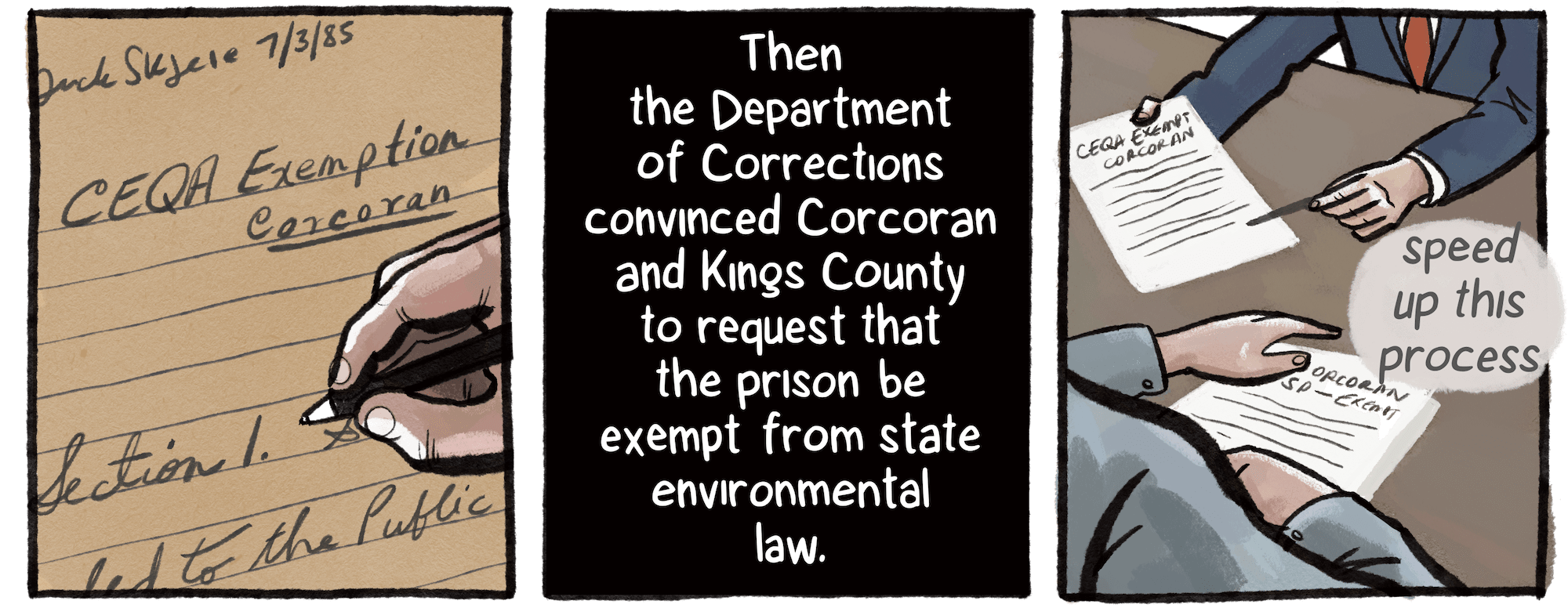

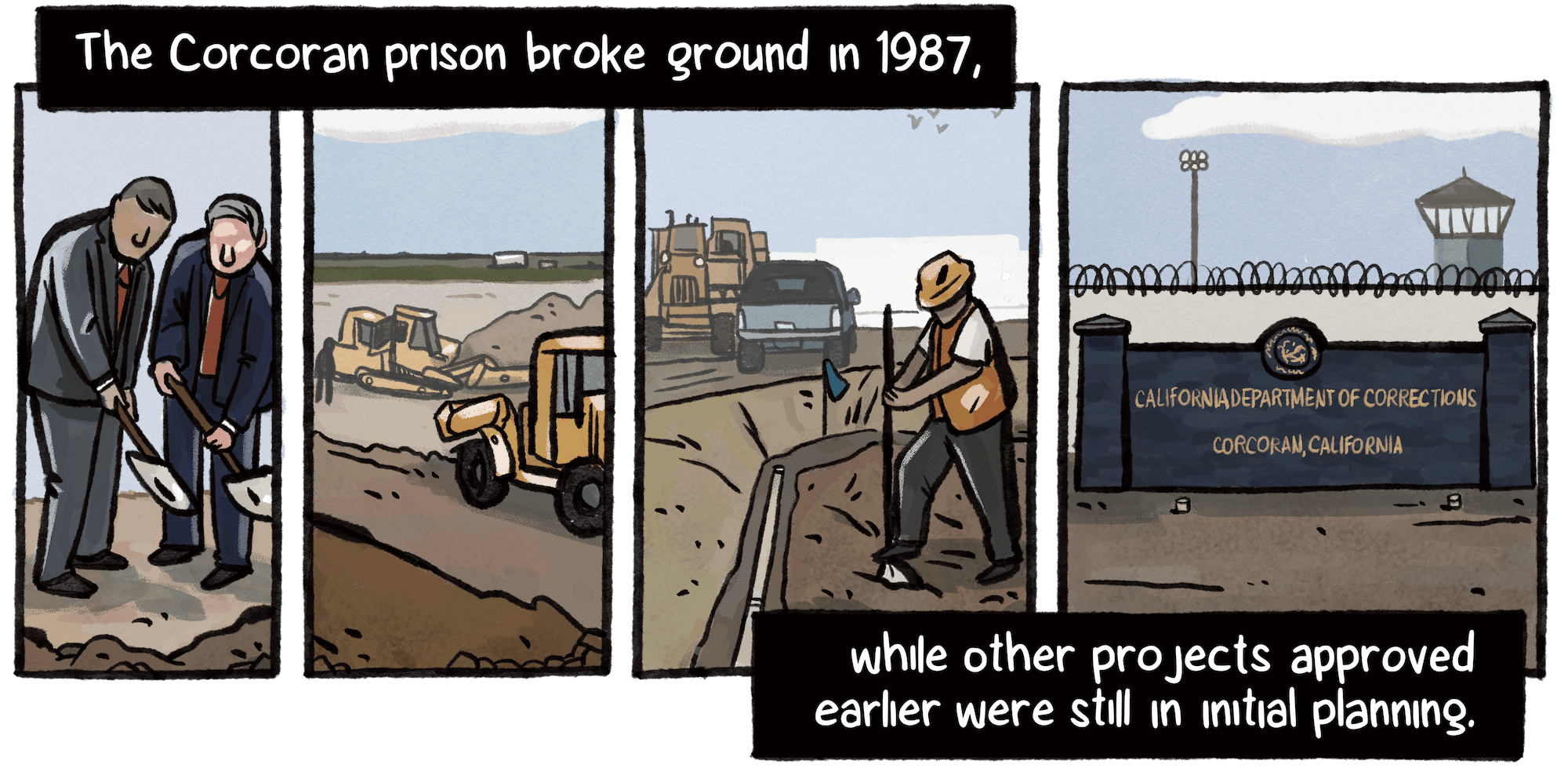

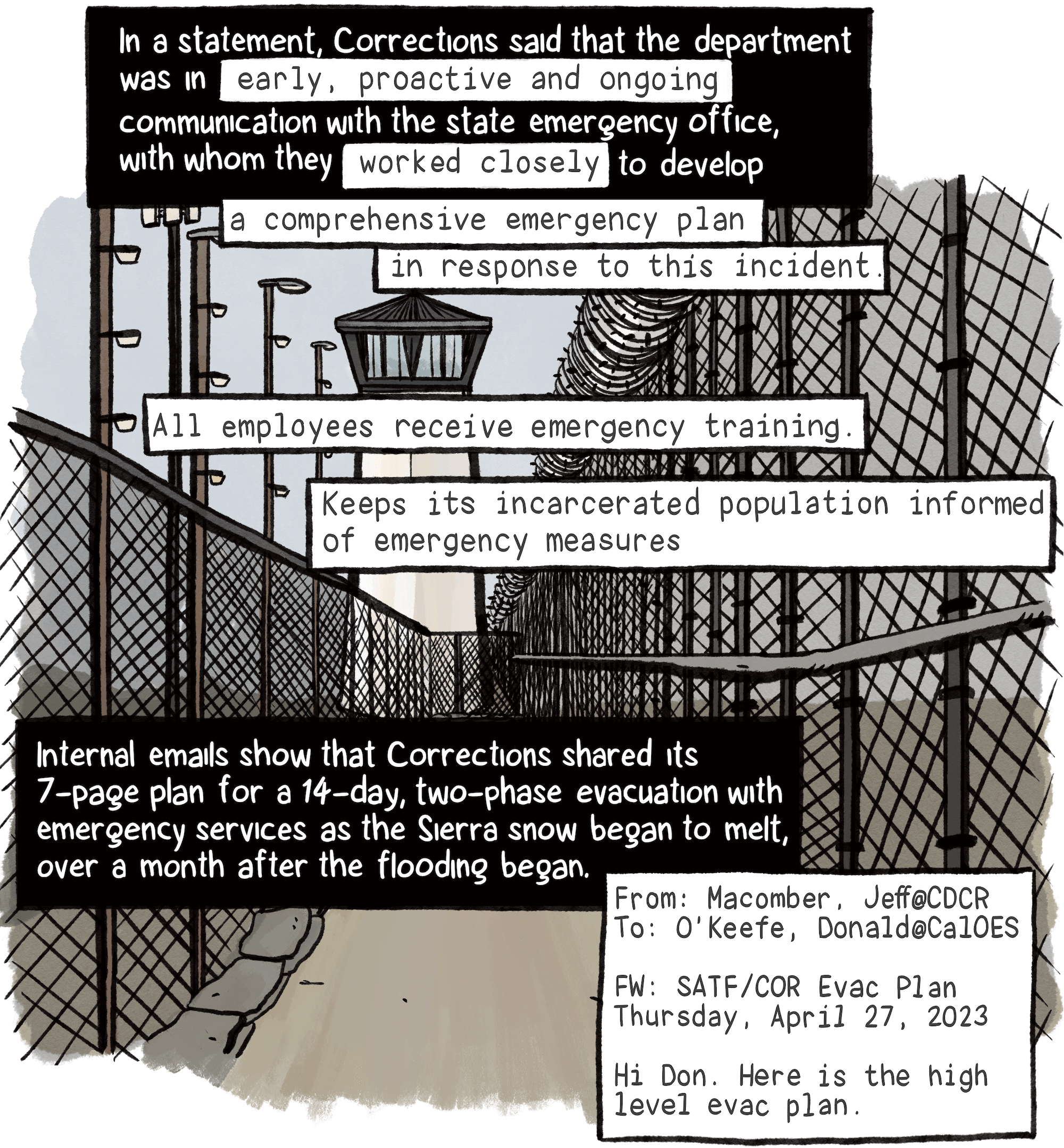

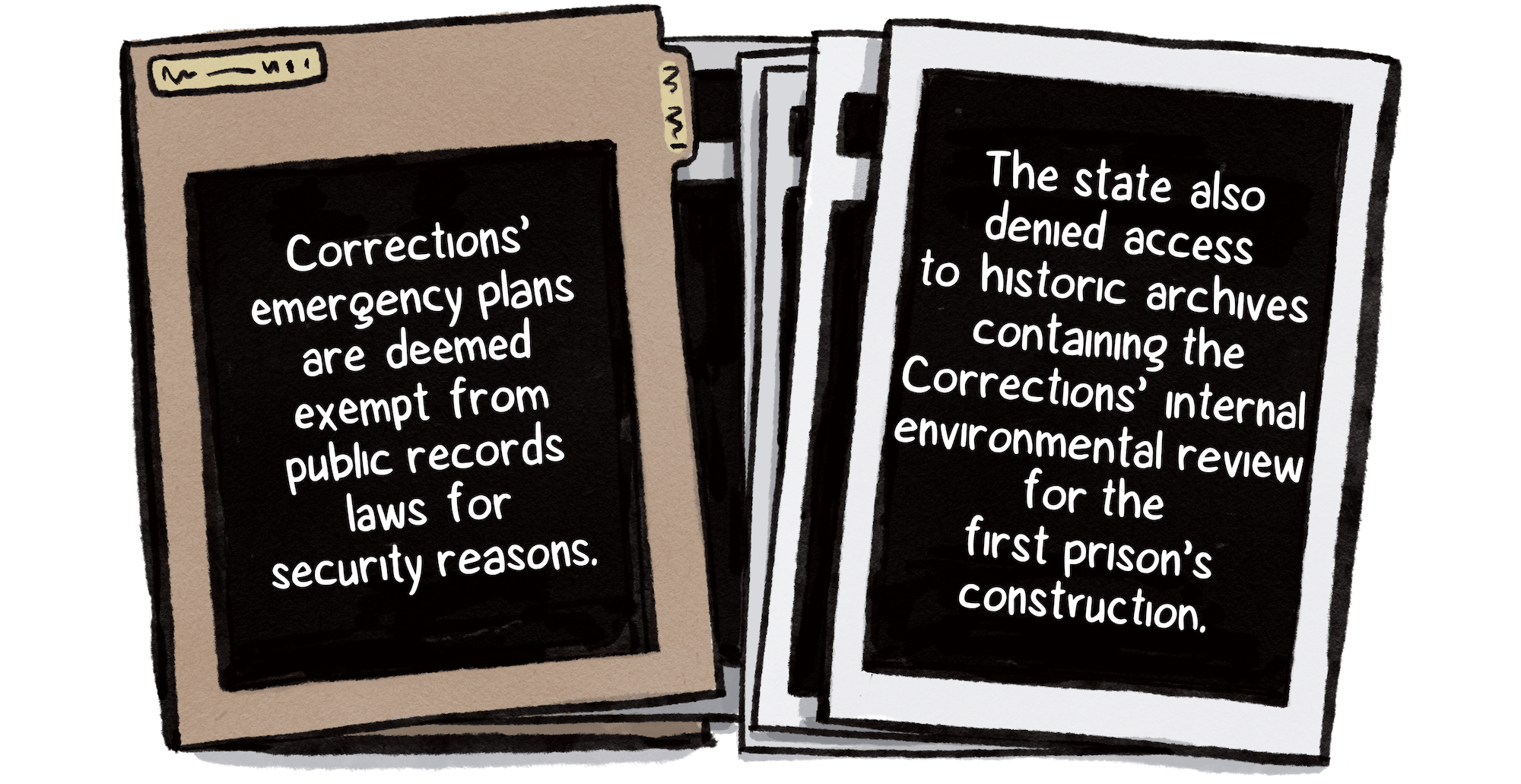

“CEQA Exemption-Corcoran” notes dated July 5, 1985, authored by attorney Dick Skjeie, held at state archives. “We are not seeking to avoid having environmental impact studies. But we are seeking to try to speed up this process,” said Gov. George Deukmejian on July 17, 1985, The Los Angeles Times.

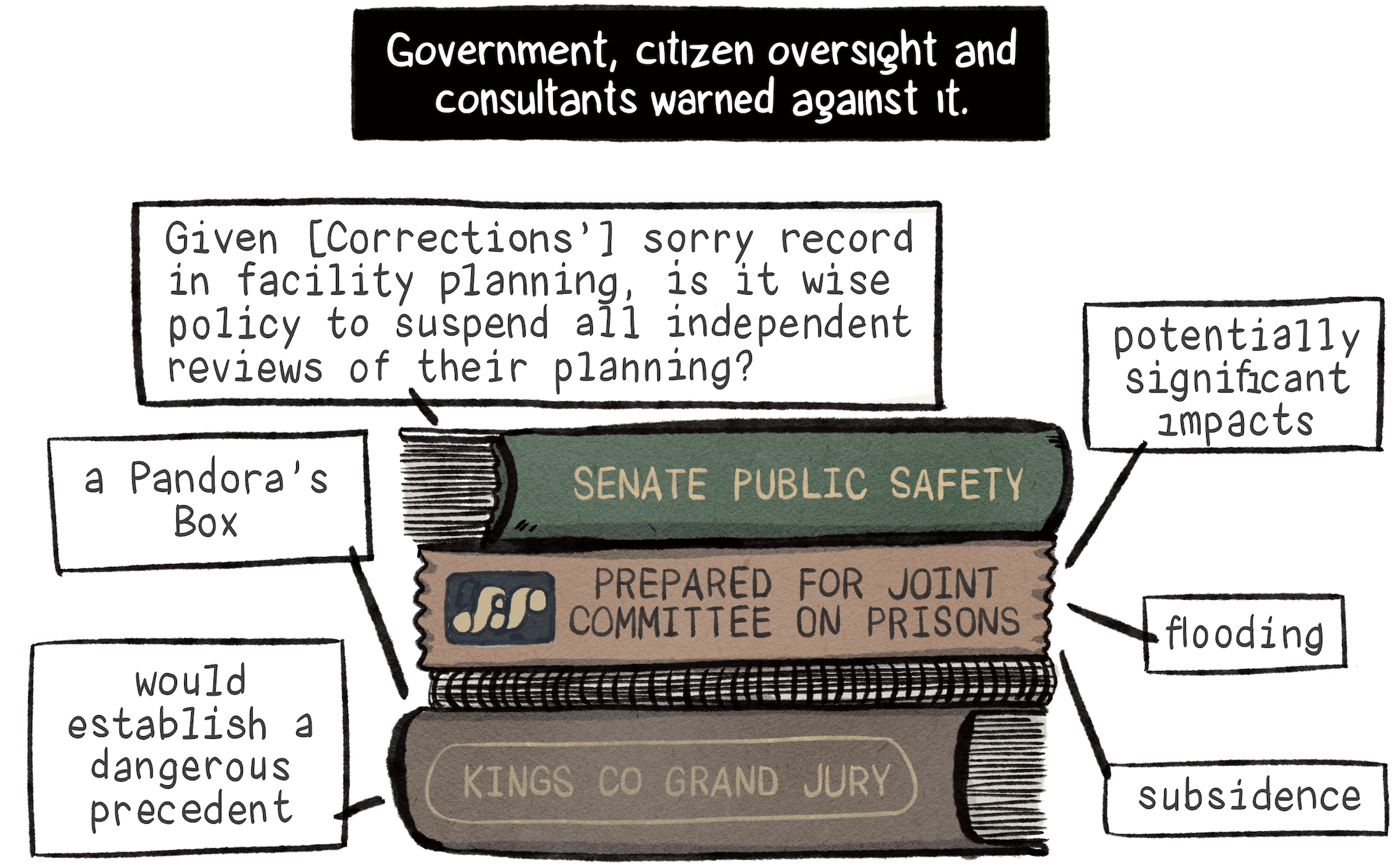

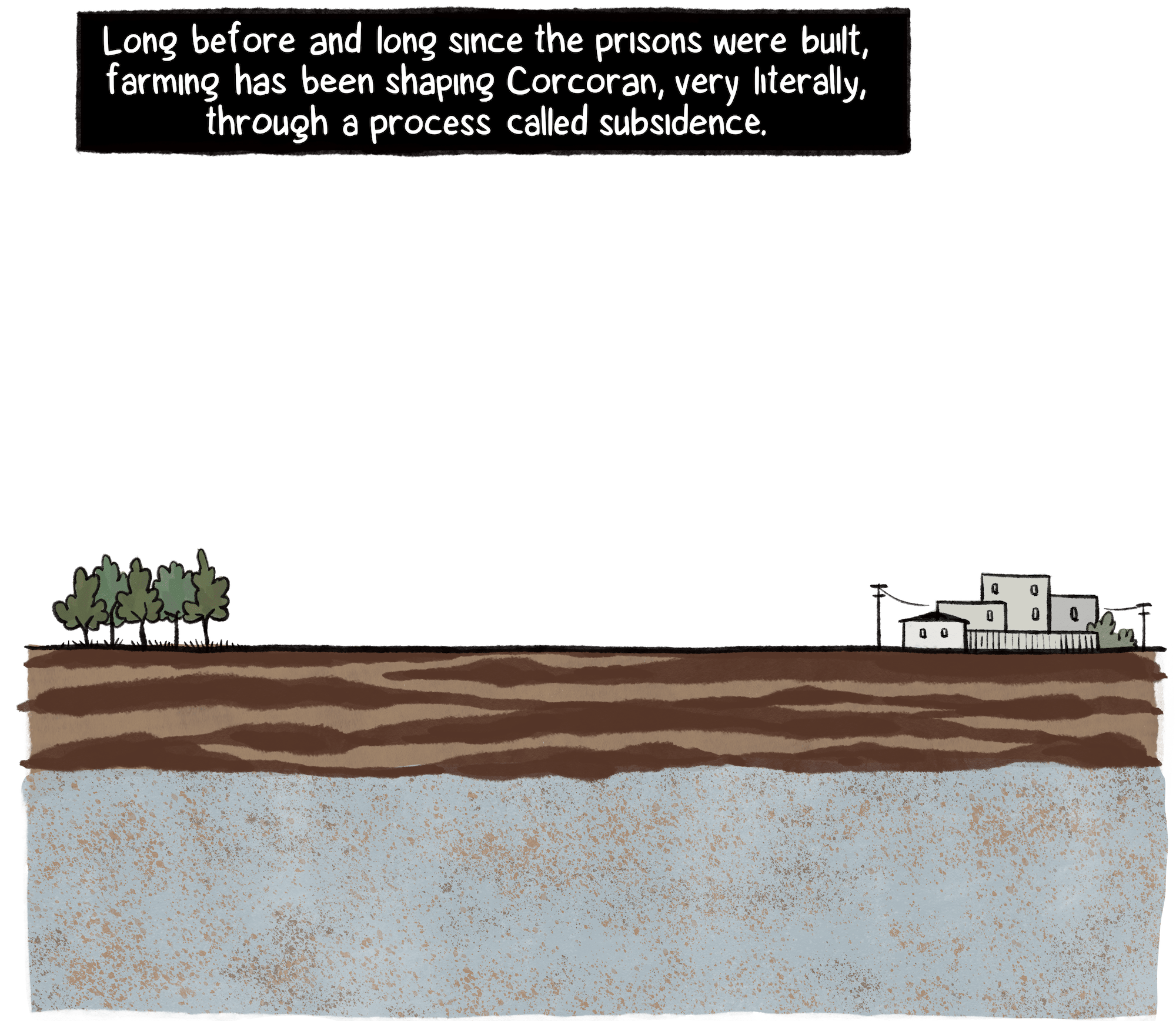

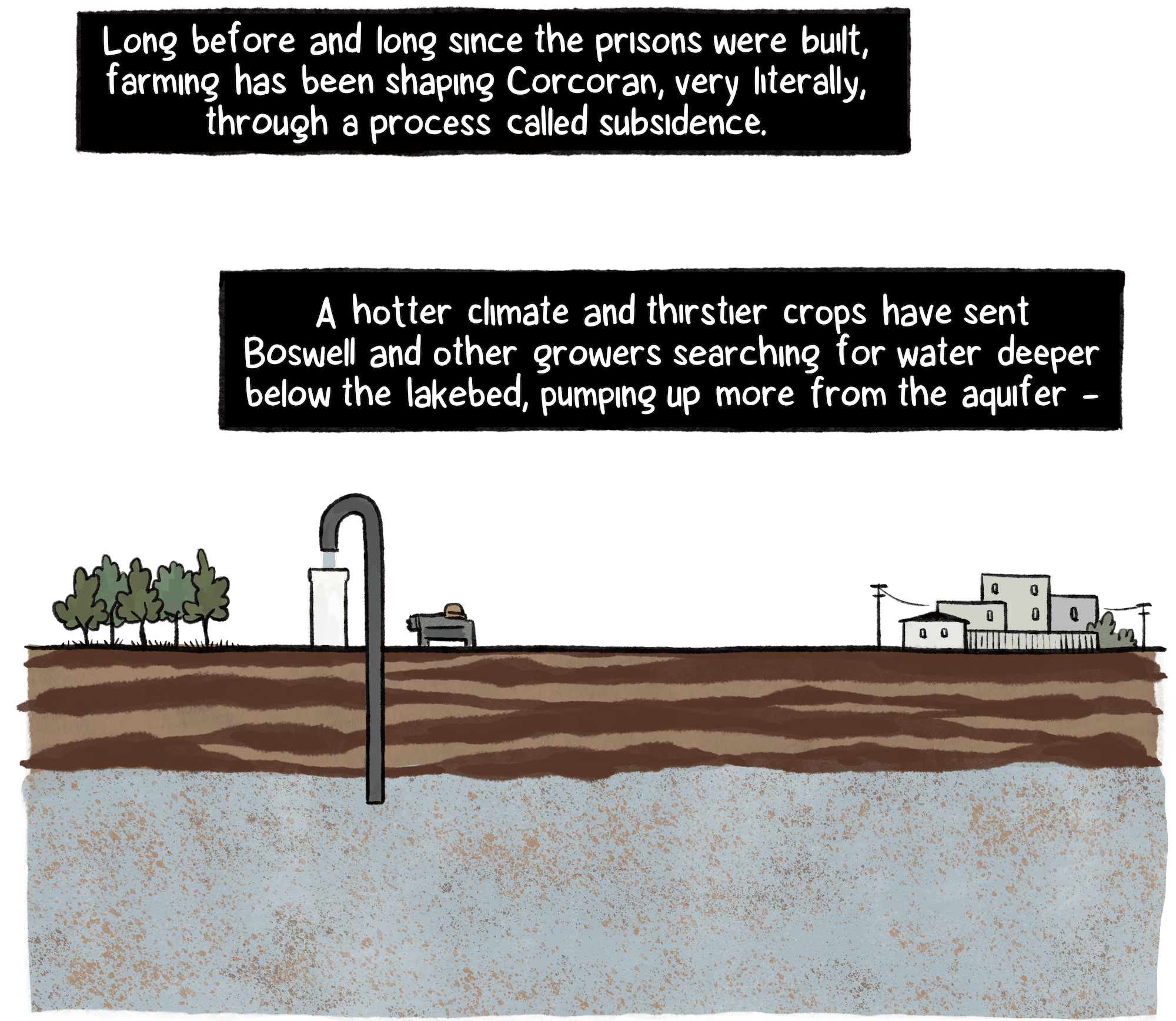

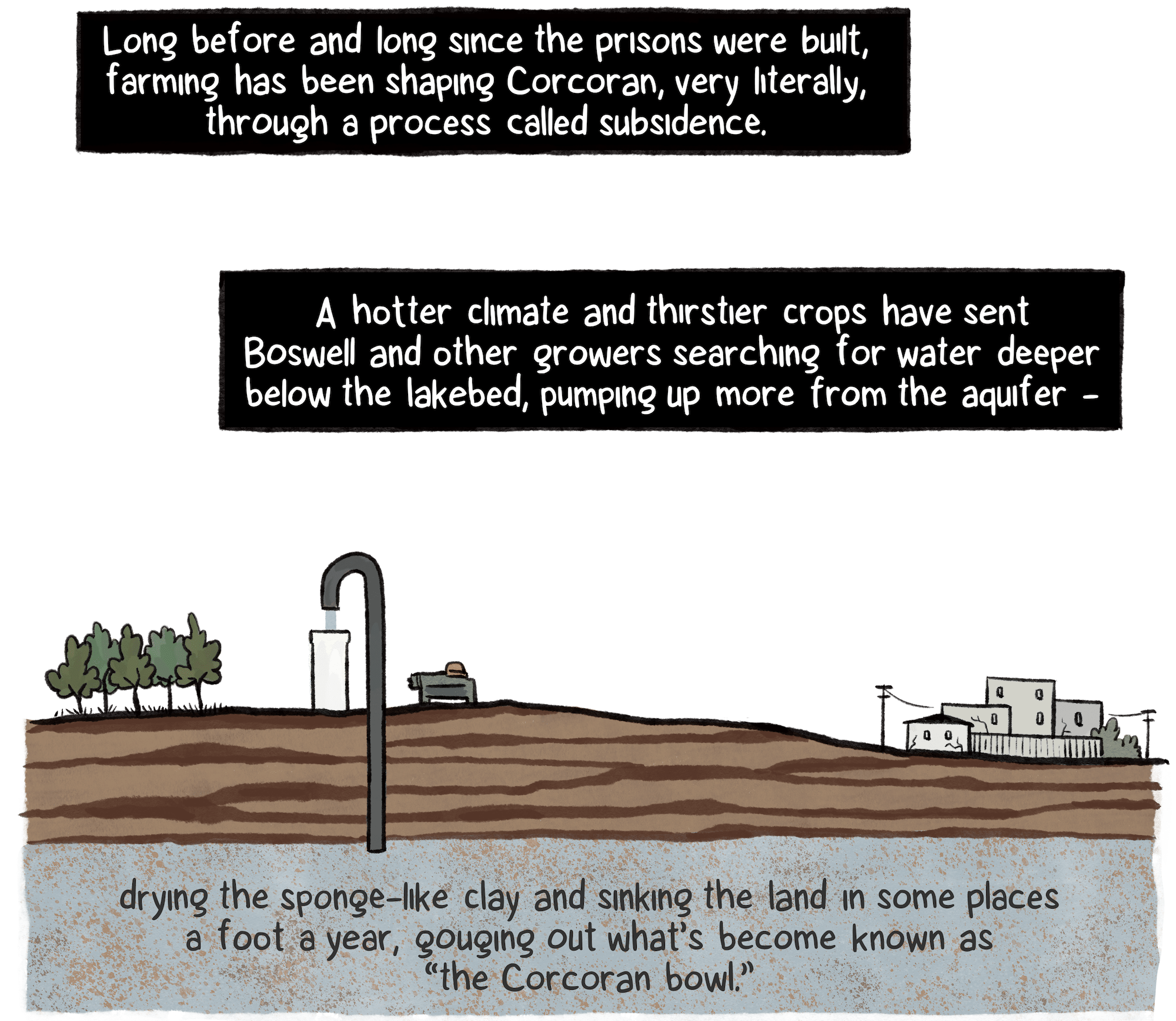

“A Pandora’s Box” and “would establish a dangerous precedent,” Kings County Grand Jury, June 13, 1985; “Given CDC’s sorry record in facility planning, is it wise policy to suspend all independent reviews of their planning?” Assembly Committee meeting notes on Senate Bill 146, August 26, 1985; “Potentially significant impacts,” “flooding,” “subsidence,” 1986 report by consultant firm Jones and Stokes assessing Corrections’ internal environmental review of the Corcoran project.

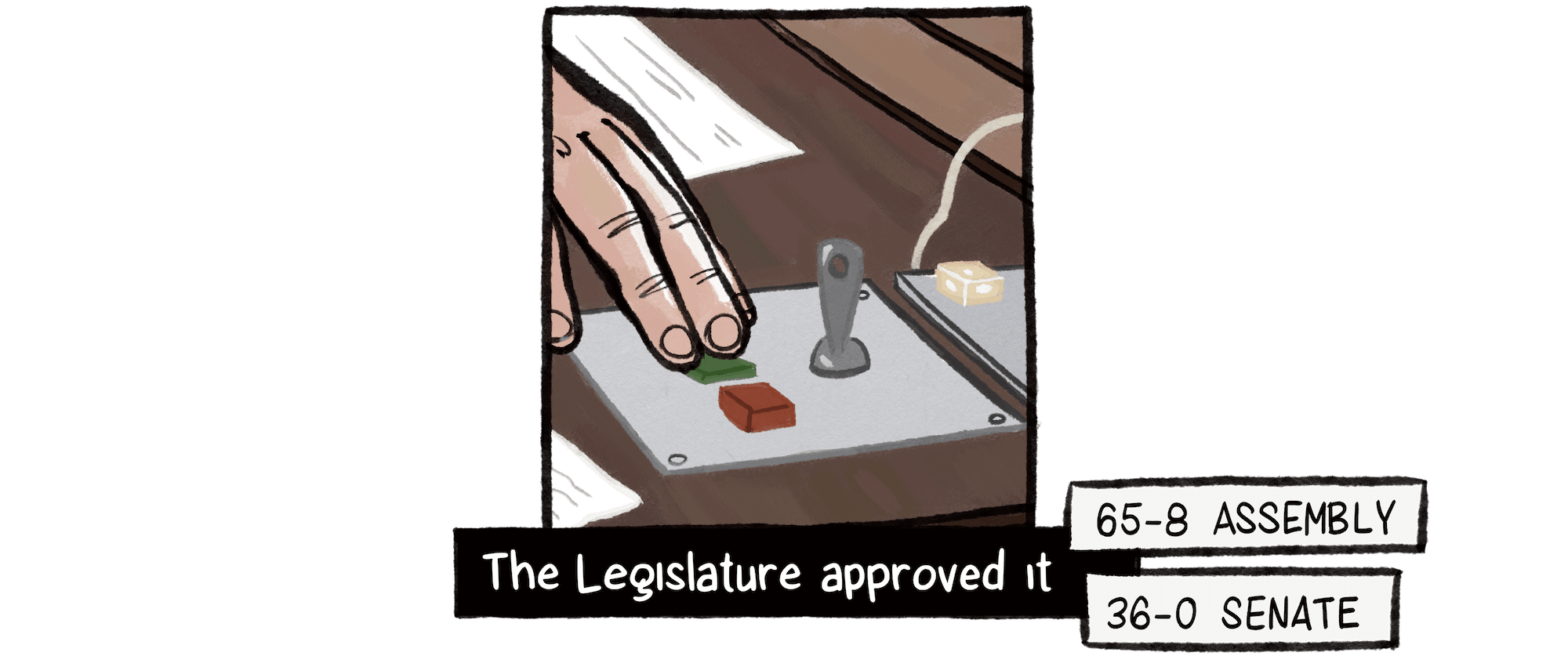

Vote count, McClatchy News Service, September 13, 1985.

Population counts, 1980 and 2020, U.S. Census Bureau.

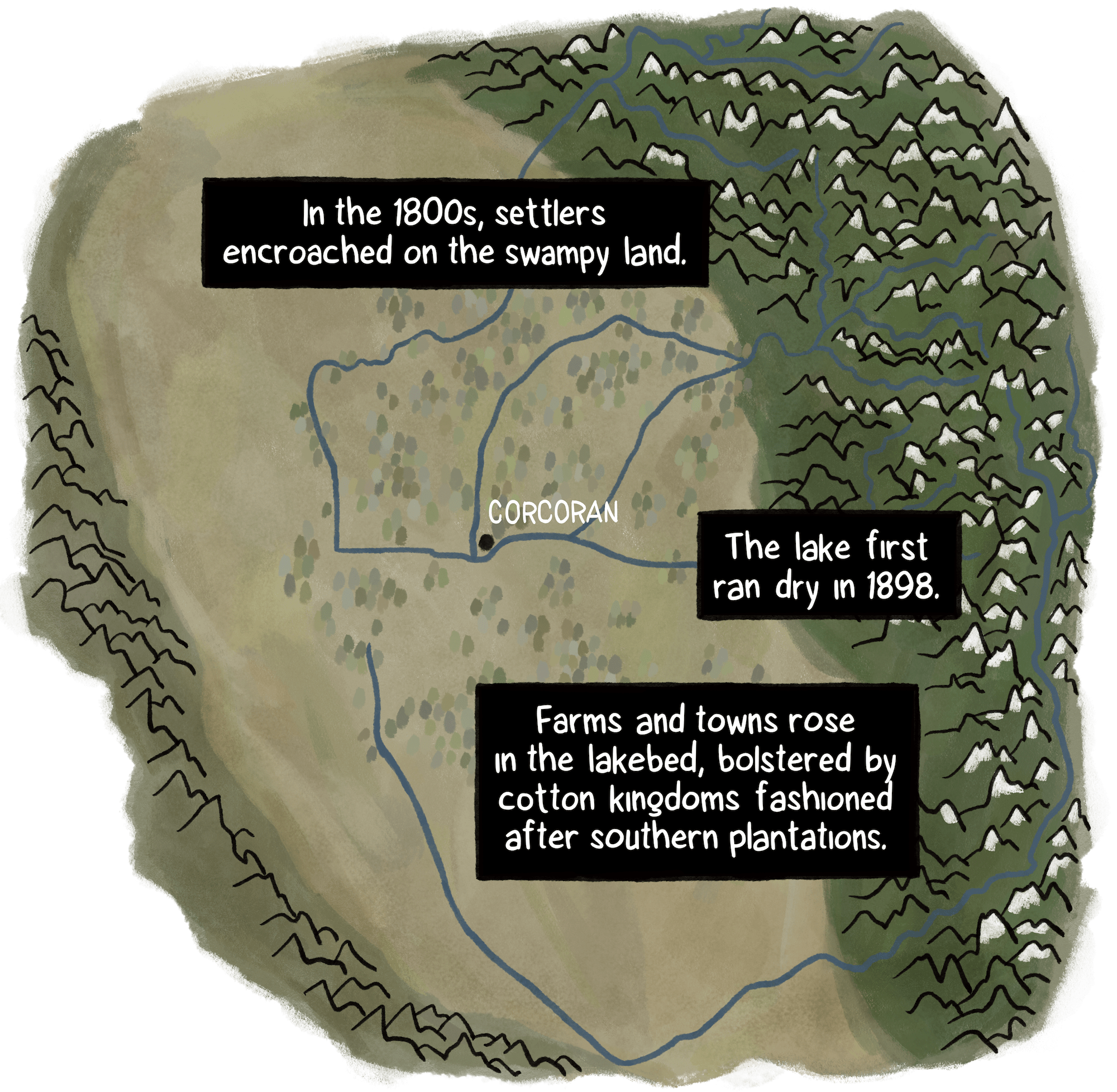

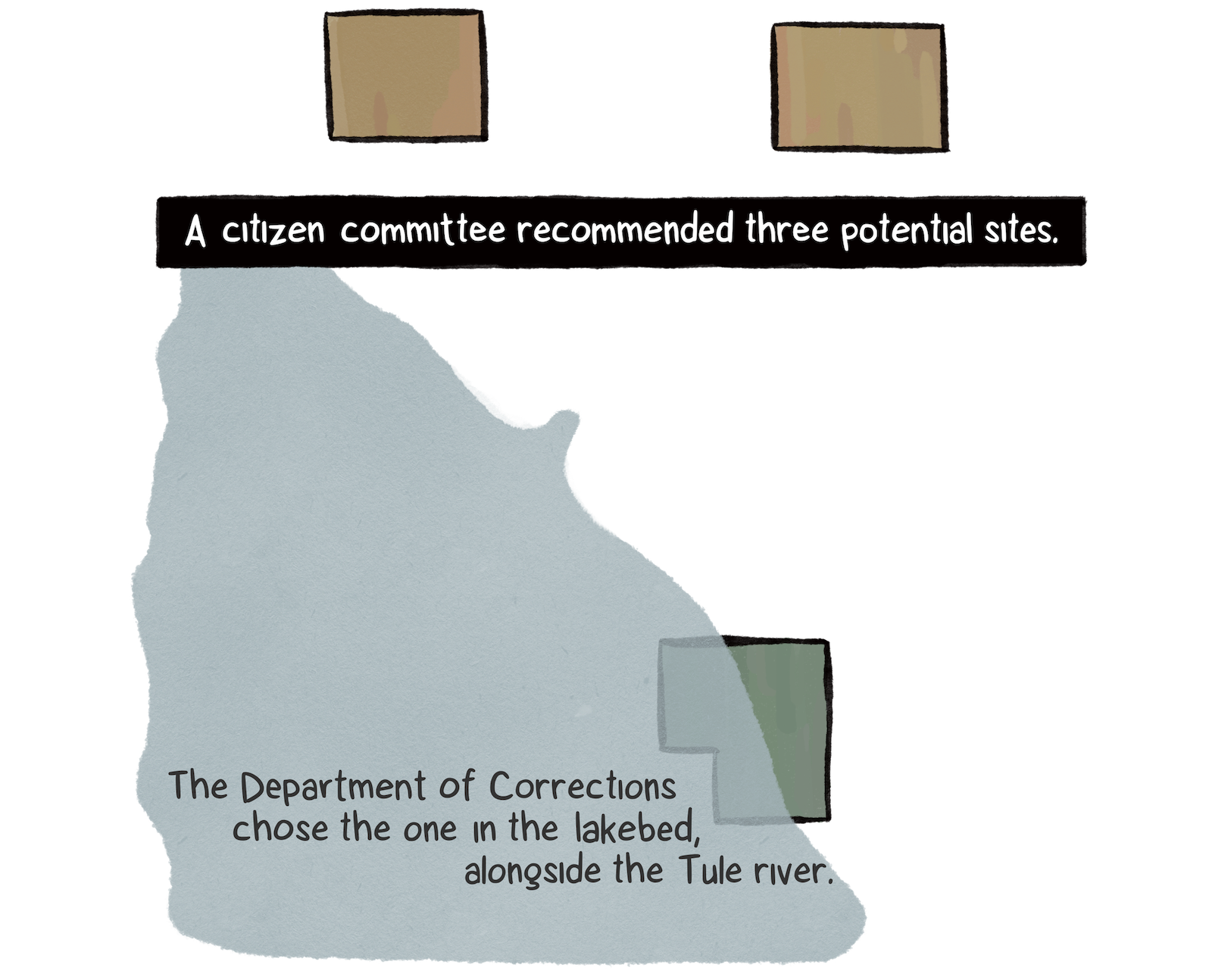

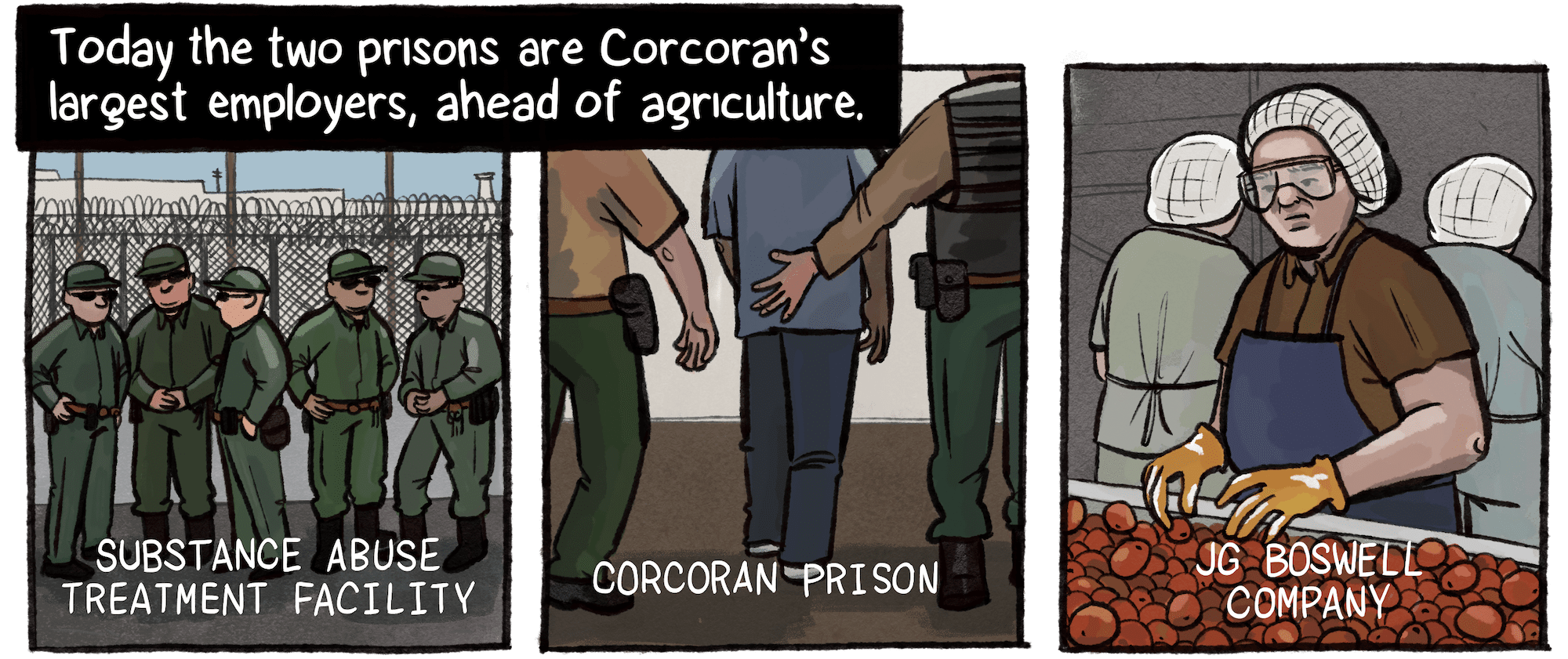

“In 1985, the CDC bought the least desirable of the three parcels from the J. G. Boswell Company,” Golden Gulag by Ruth Wilson Gilmore. Boswell land ownership data, ParcelQuest.

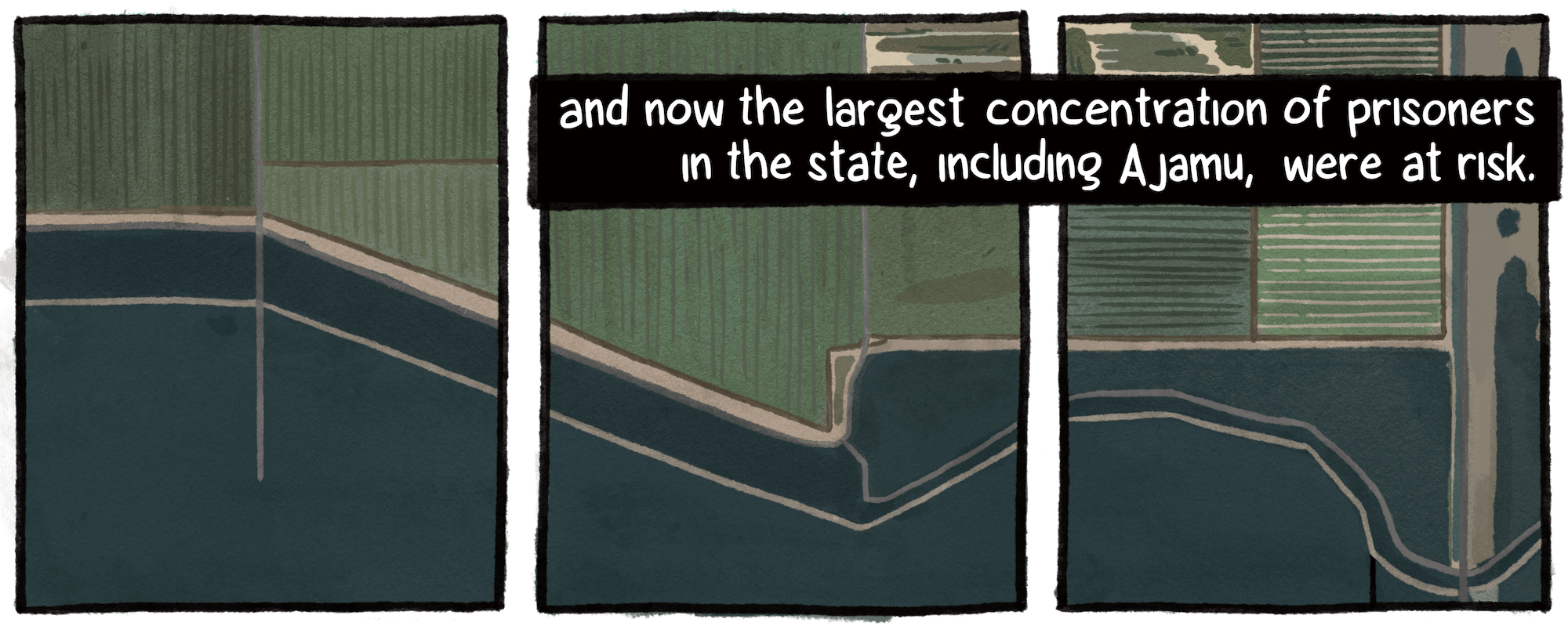

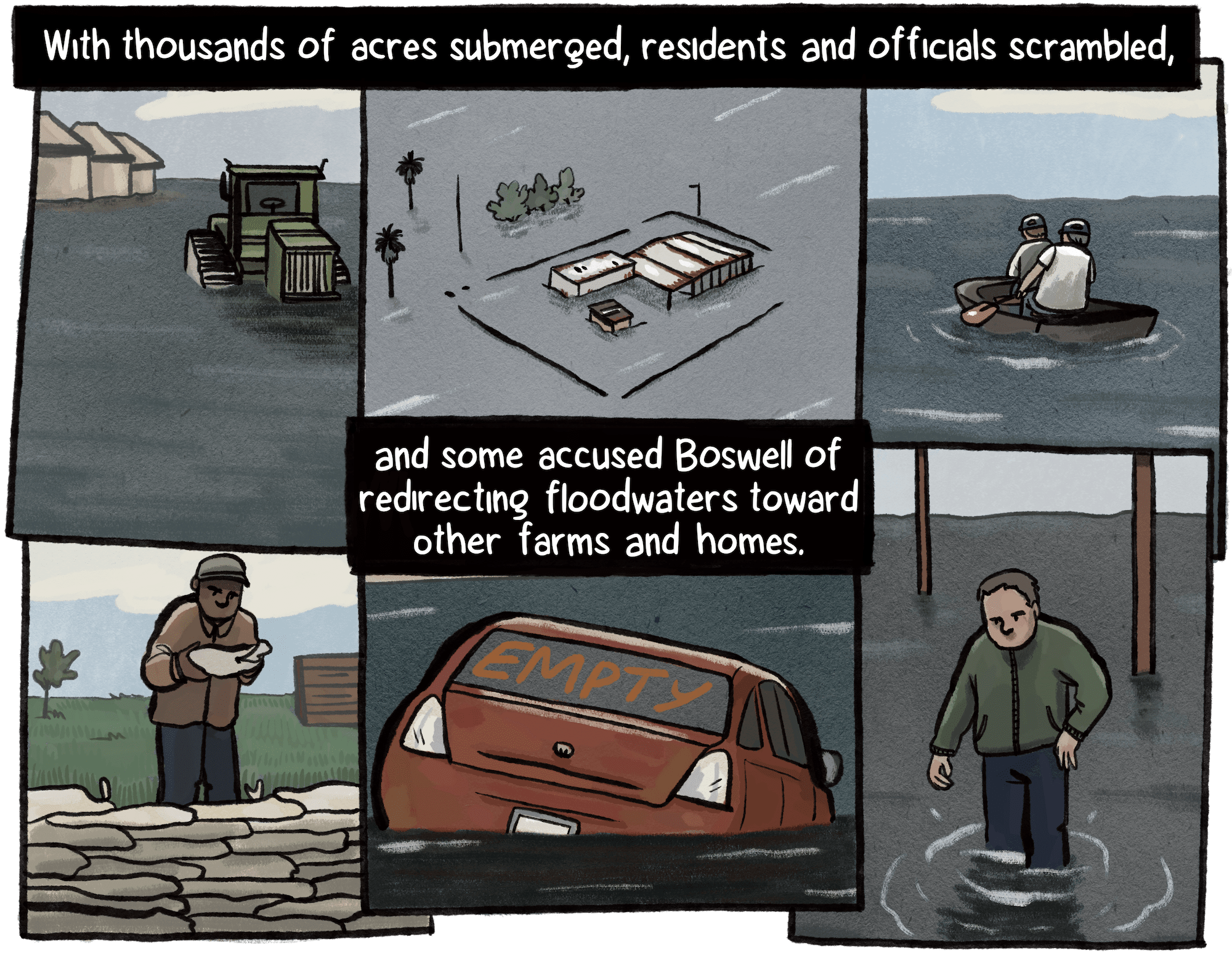

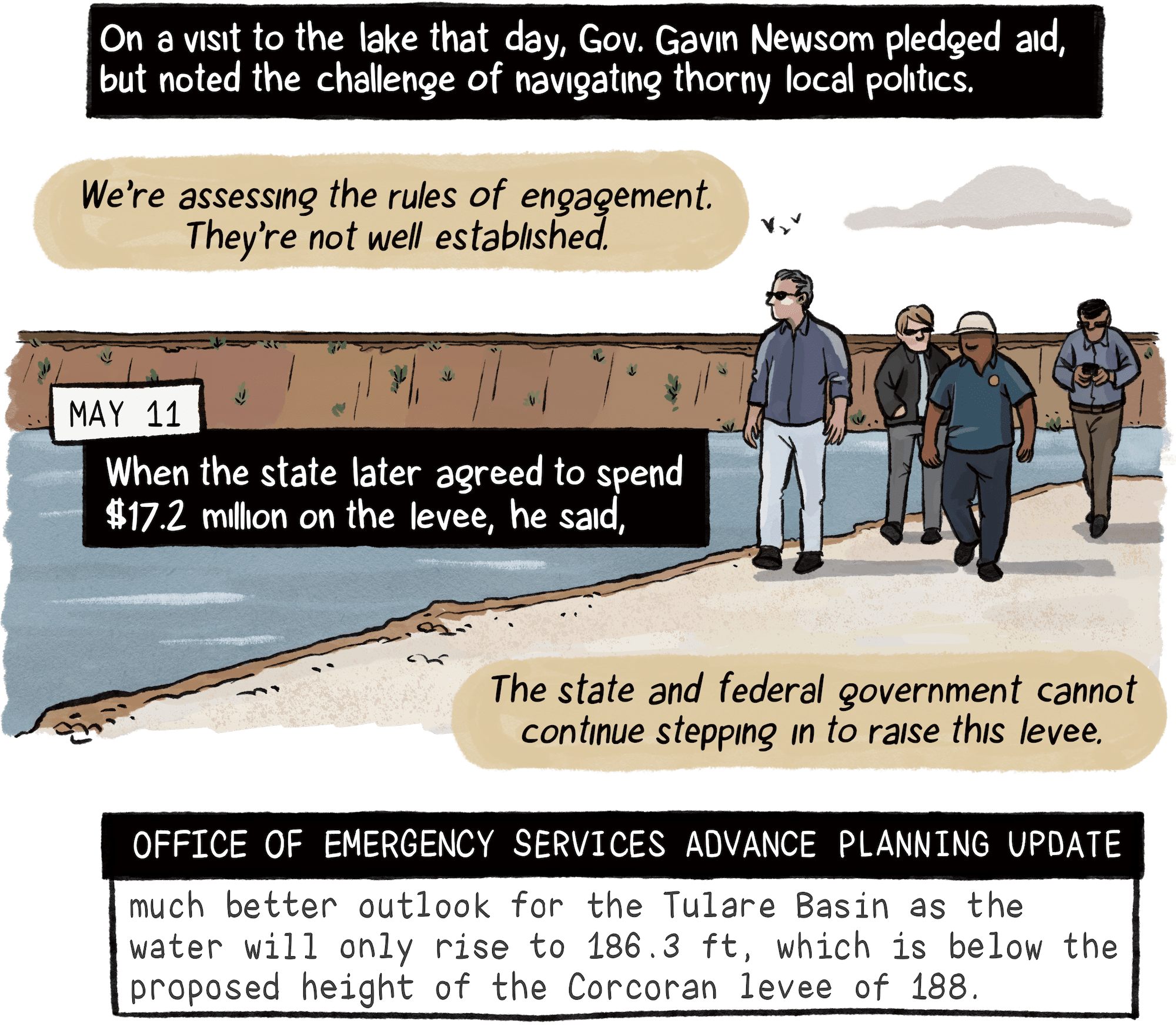

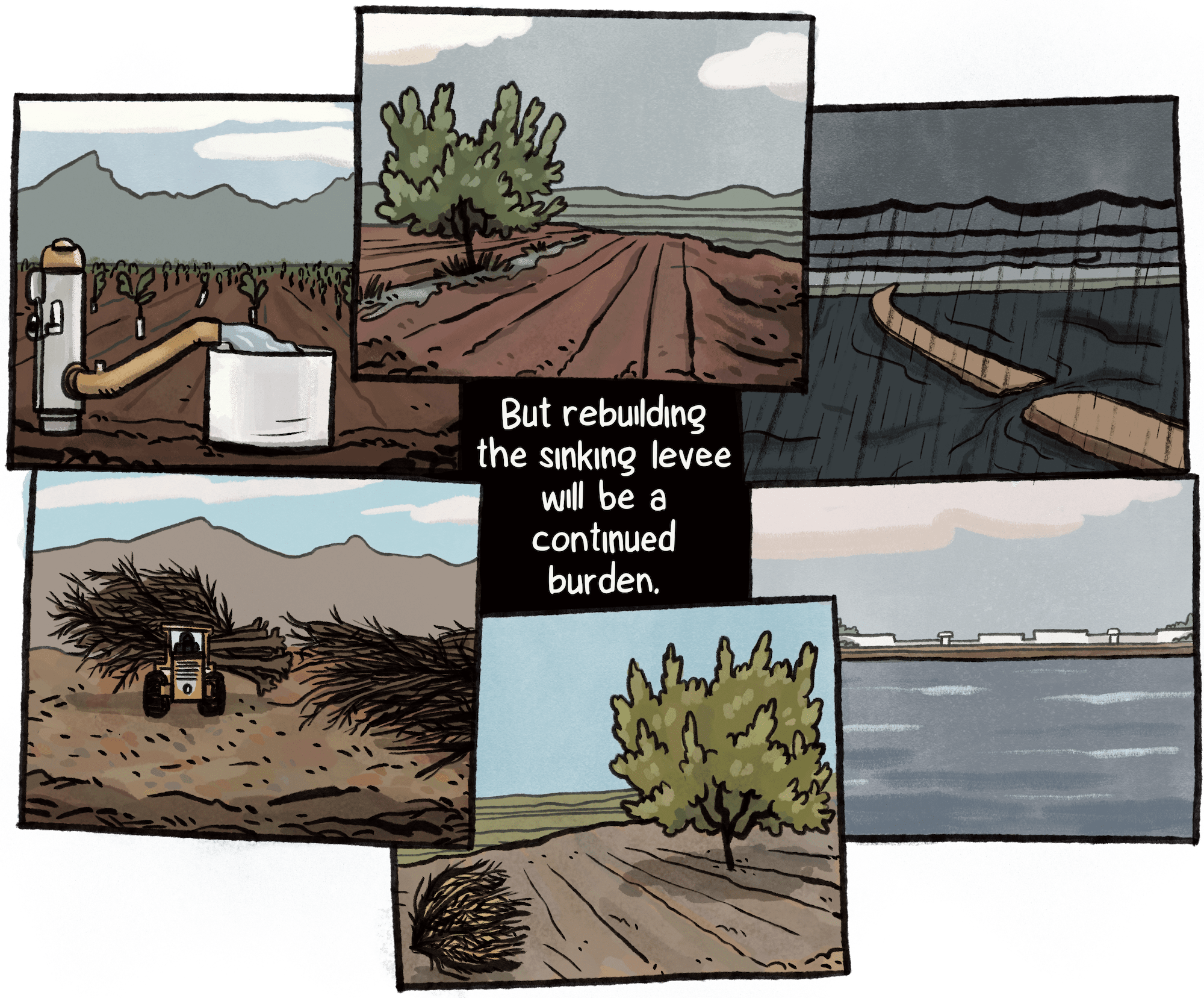

Mark Grewal, former Boswell Company VP, calculated the flooded acreage using local flood district maps and observations, estimating the lake grew 10,000 acres each week in the initial flood phase.

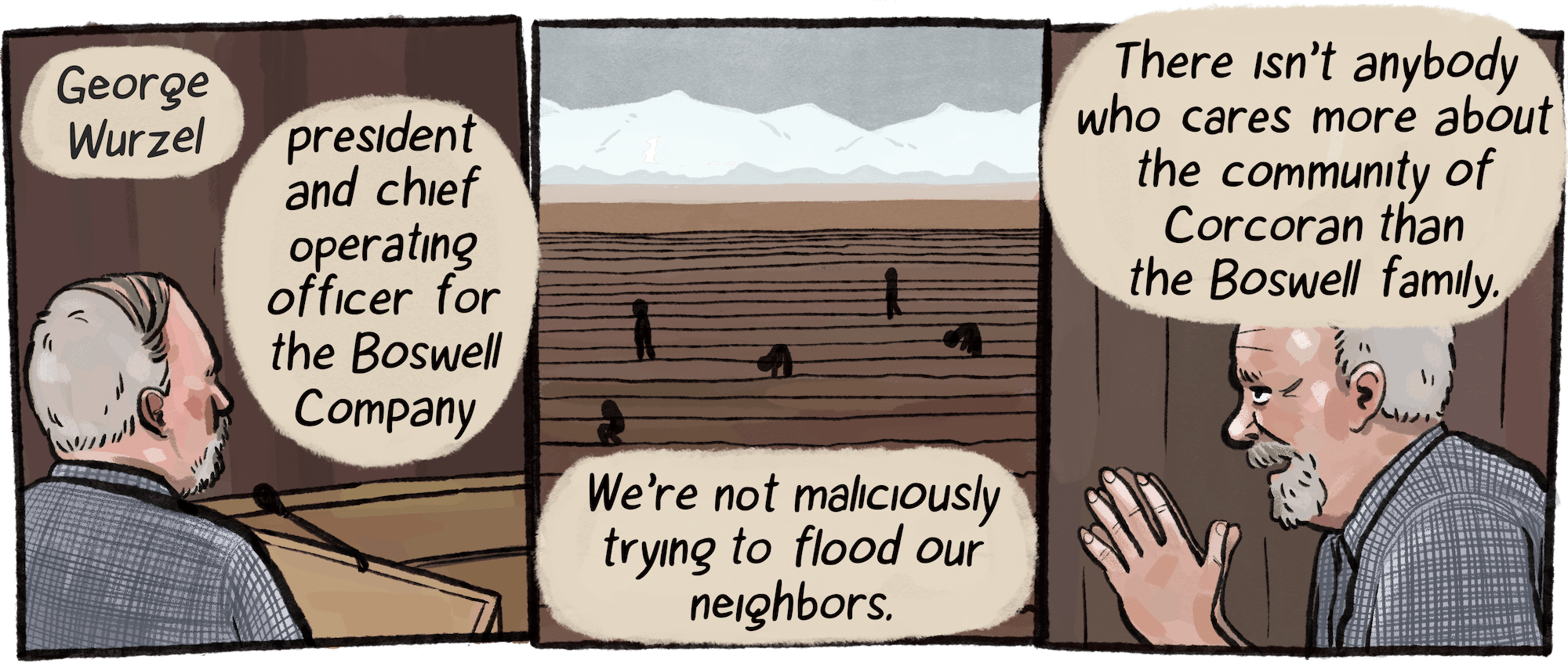

Repeated attempts to reach Boswell officials for comment went unanswered.

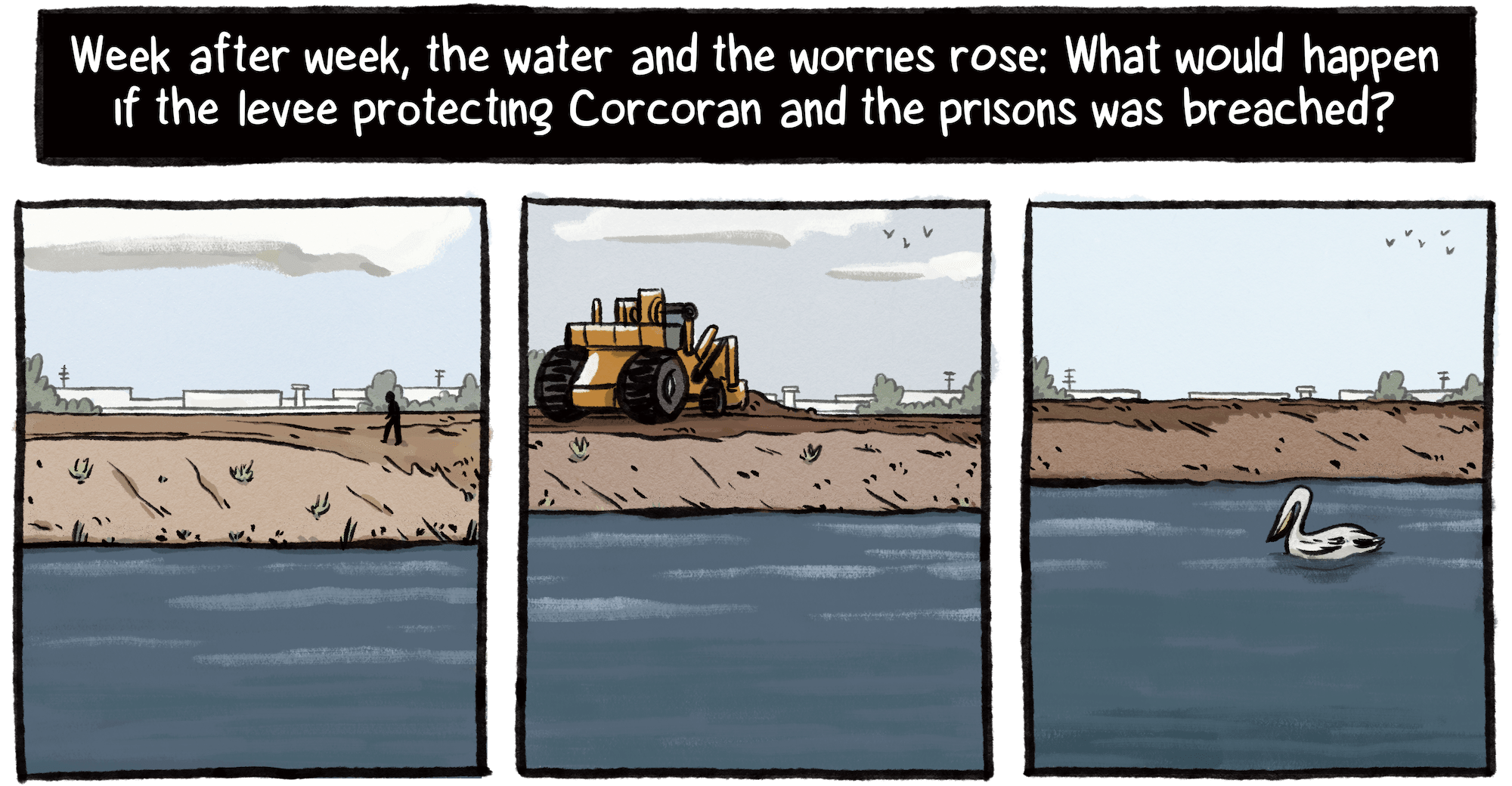

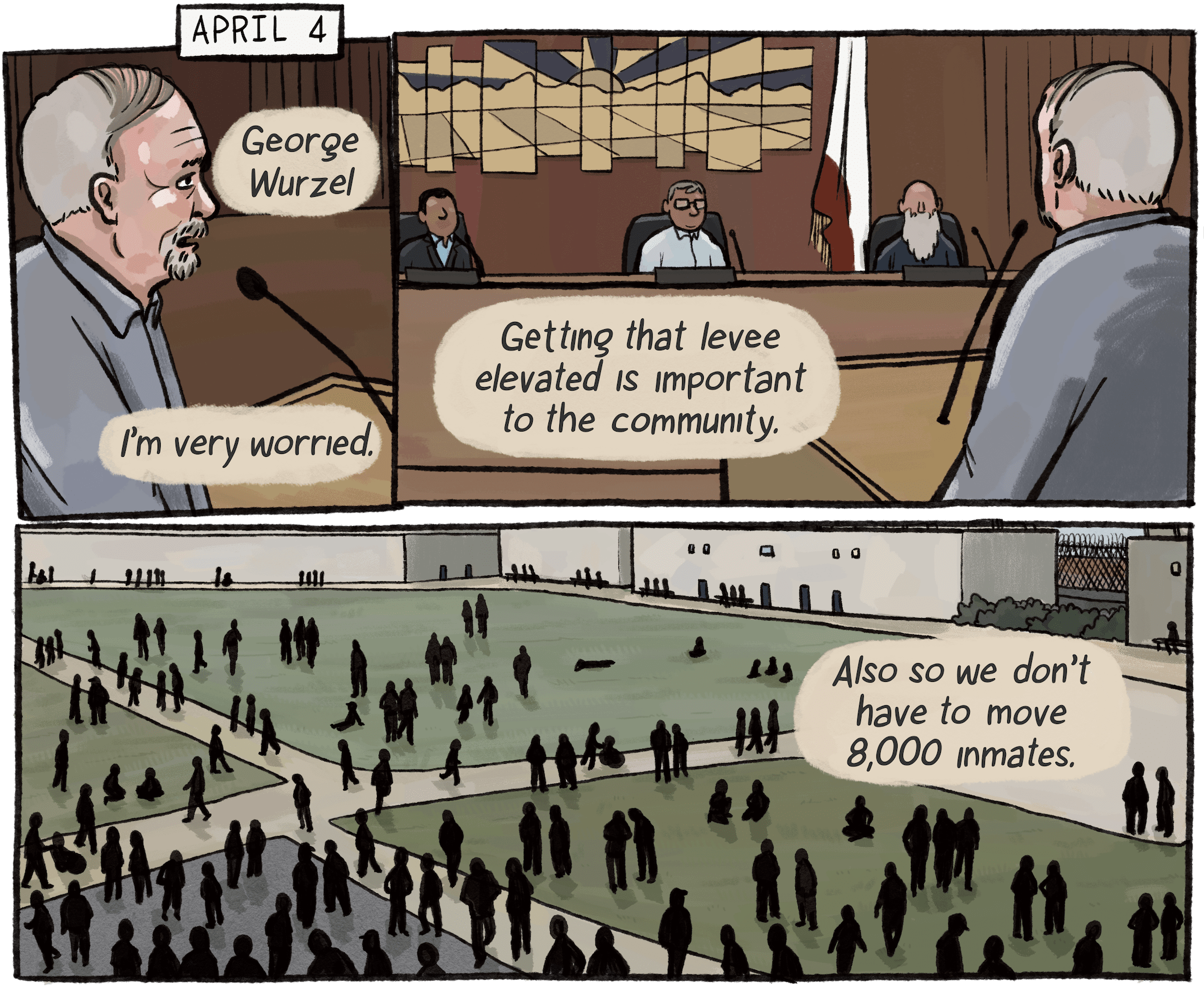

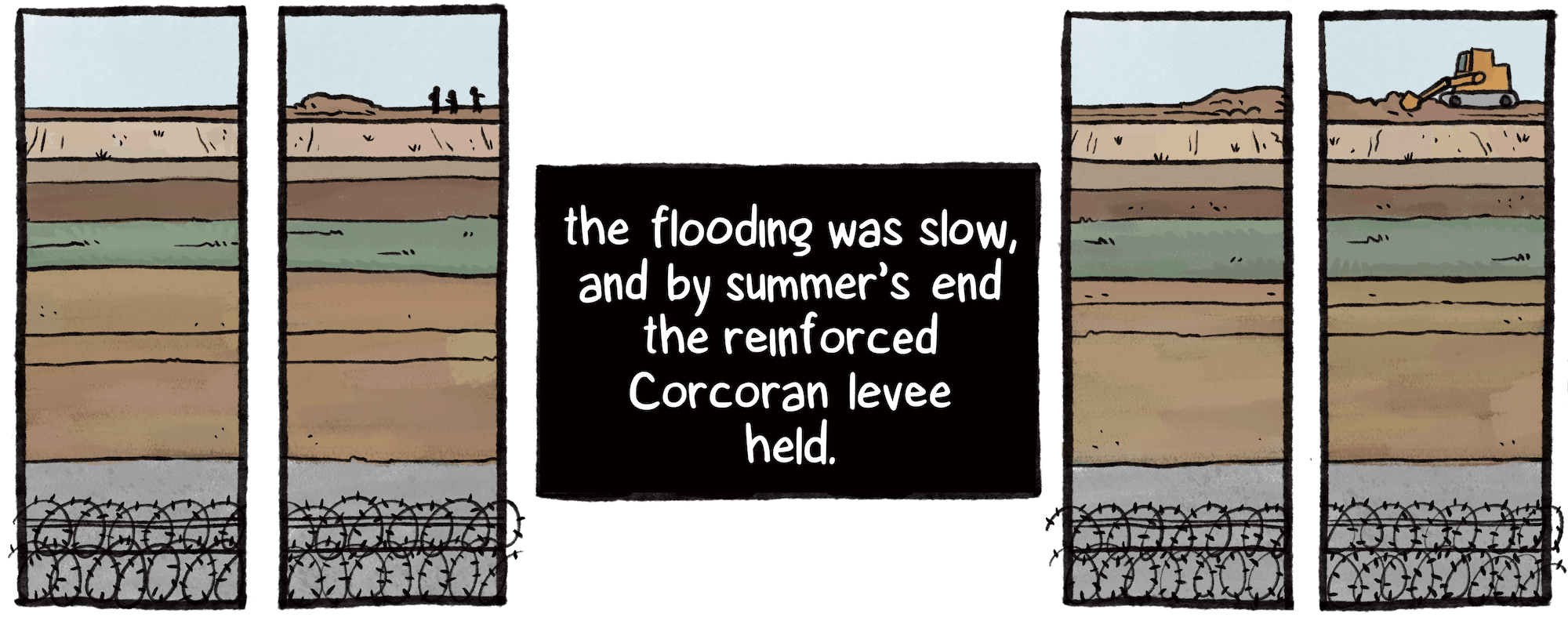

2015 and 2017 levee work, Hanford Sentinel, August 30, 2017; “Ground Subsidence Study Report, Corcoran Subsidence Bowl,” Amec Foster Wheeler Environment & Infrastructure, 2017; 1969 and 1983 flood satellite images provided by Rob Hansen; 2023 flood map, California Department of Water Resources.

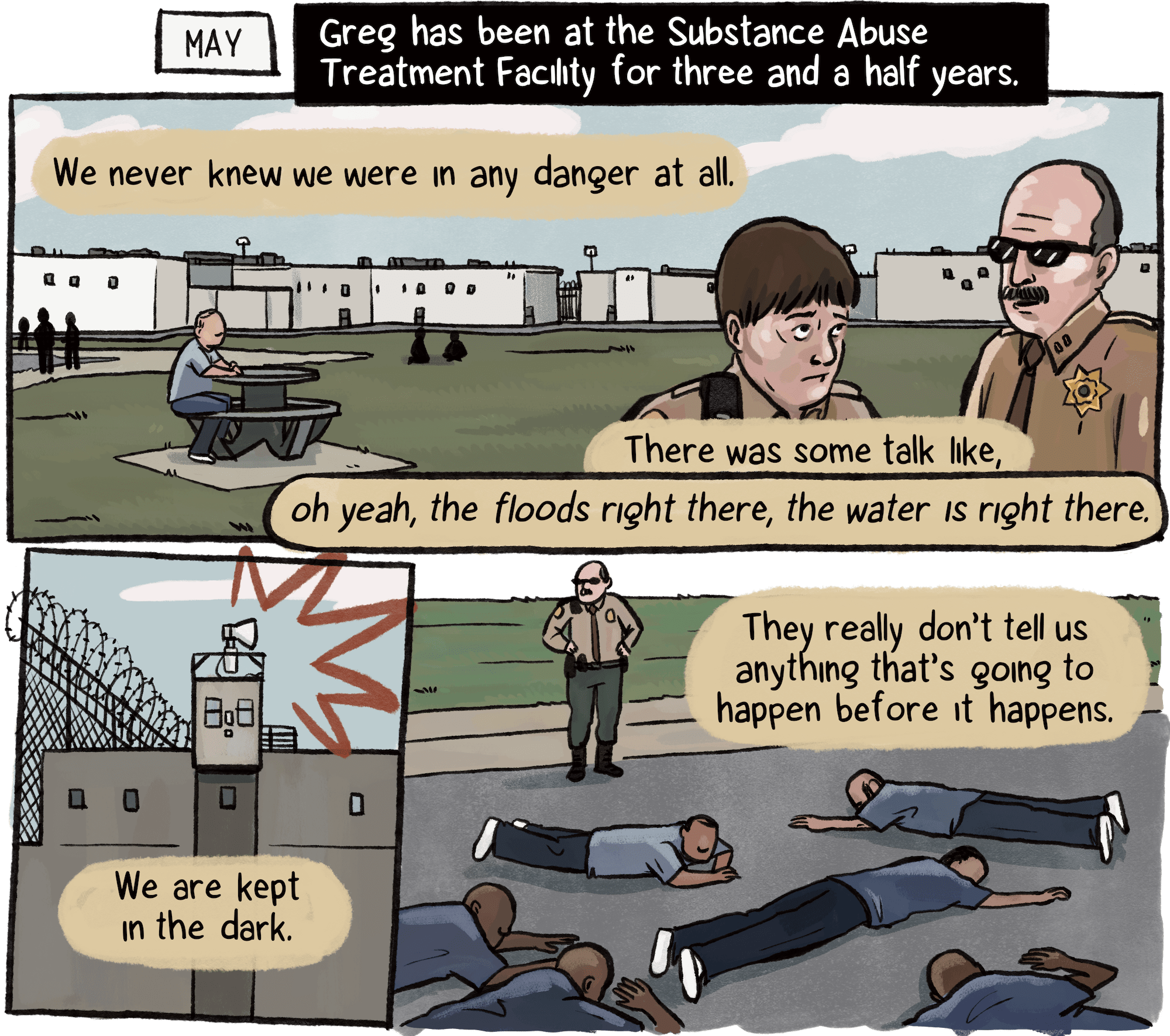

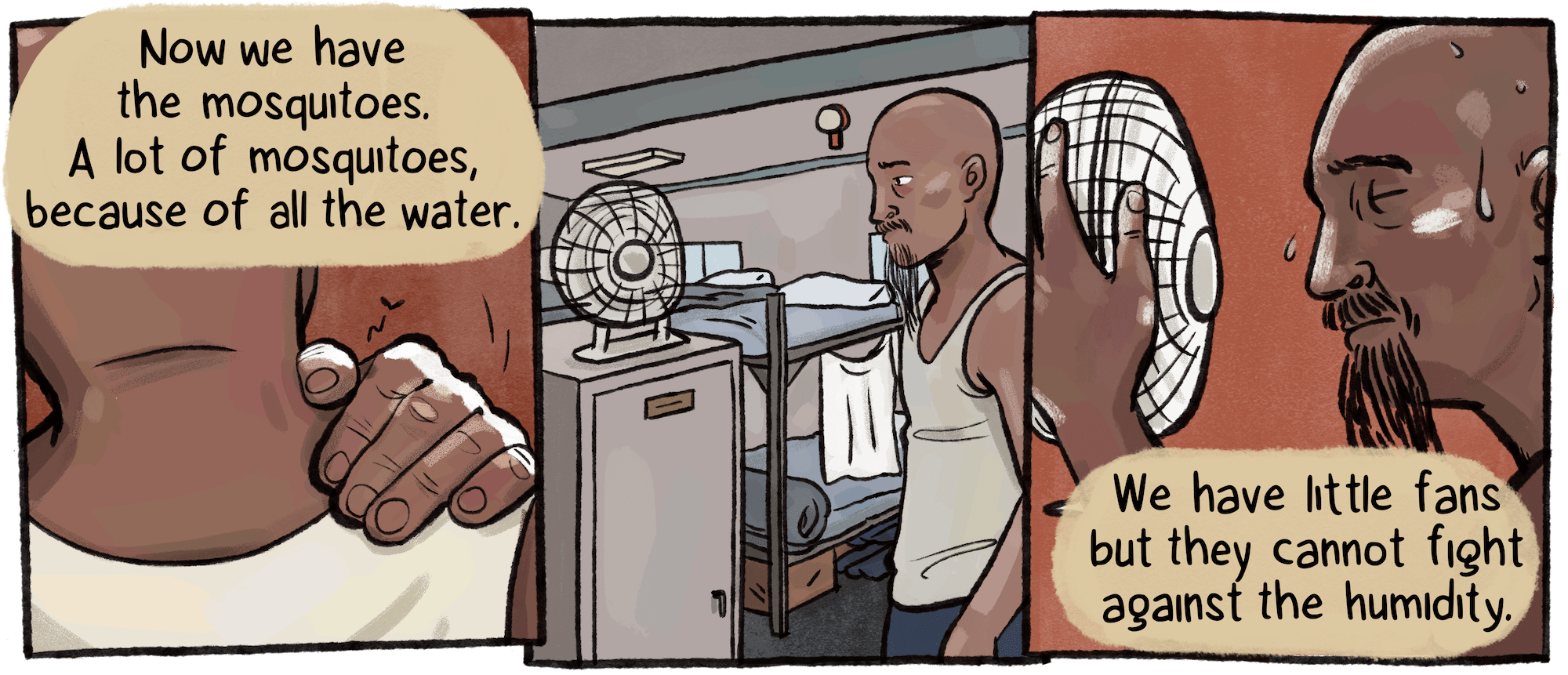

Greg, an incarcerated person at SATF, asked that his last name be withheld because he feared retribution for speaking to a reporter.

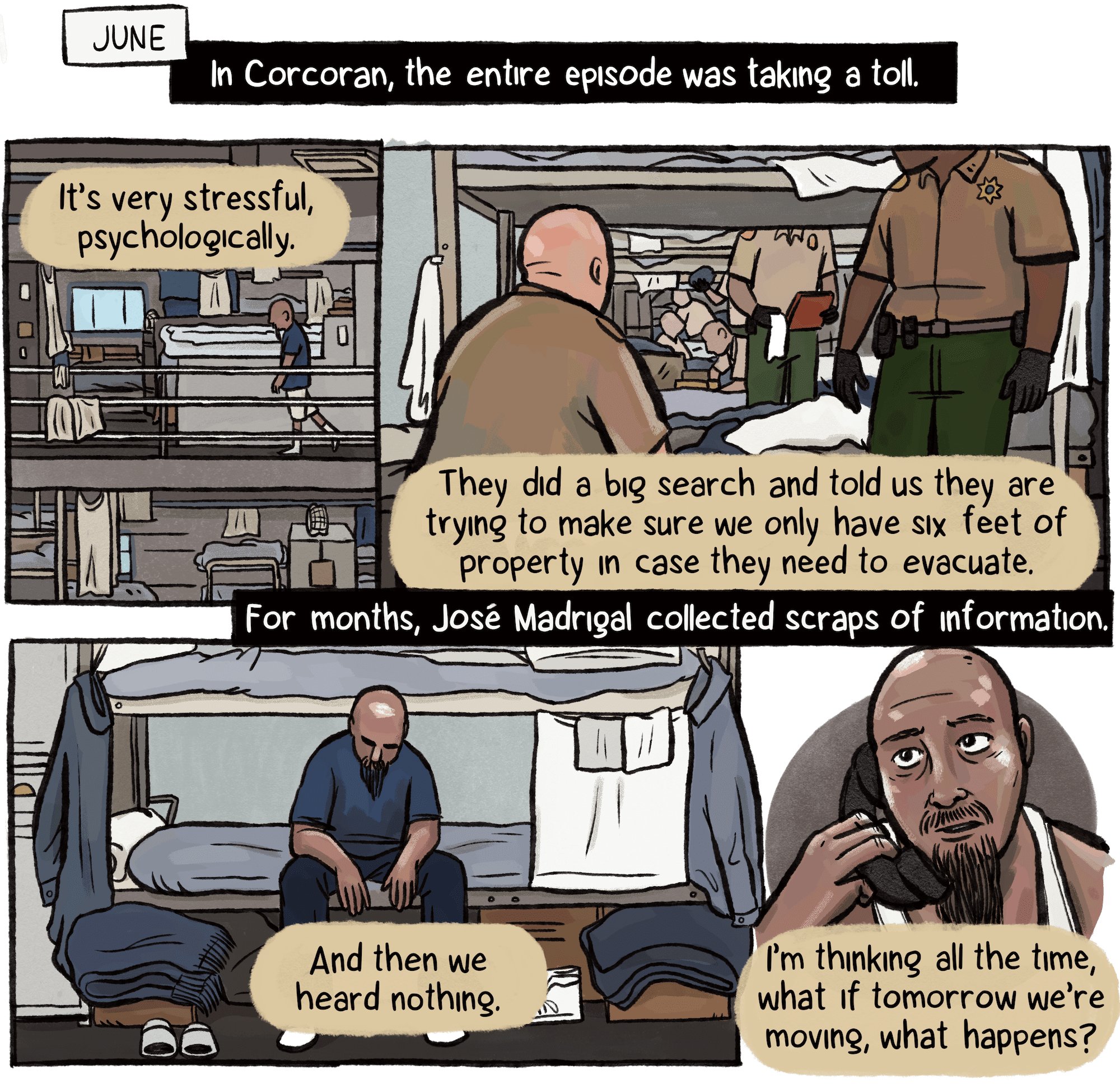

José Madrigal spoke with TMP over the course of several months in the late spring and summer.

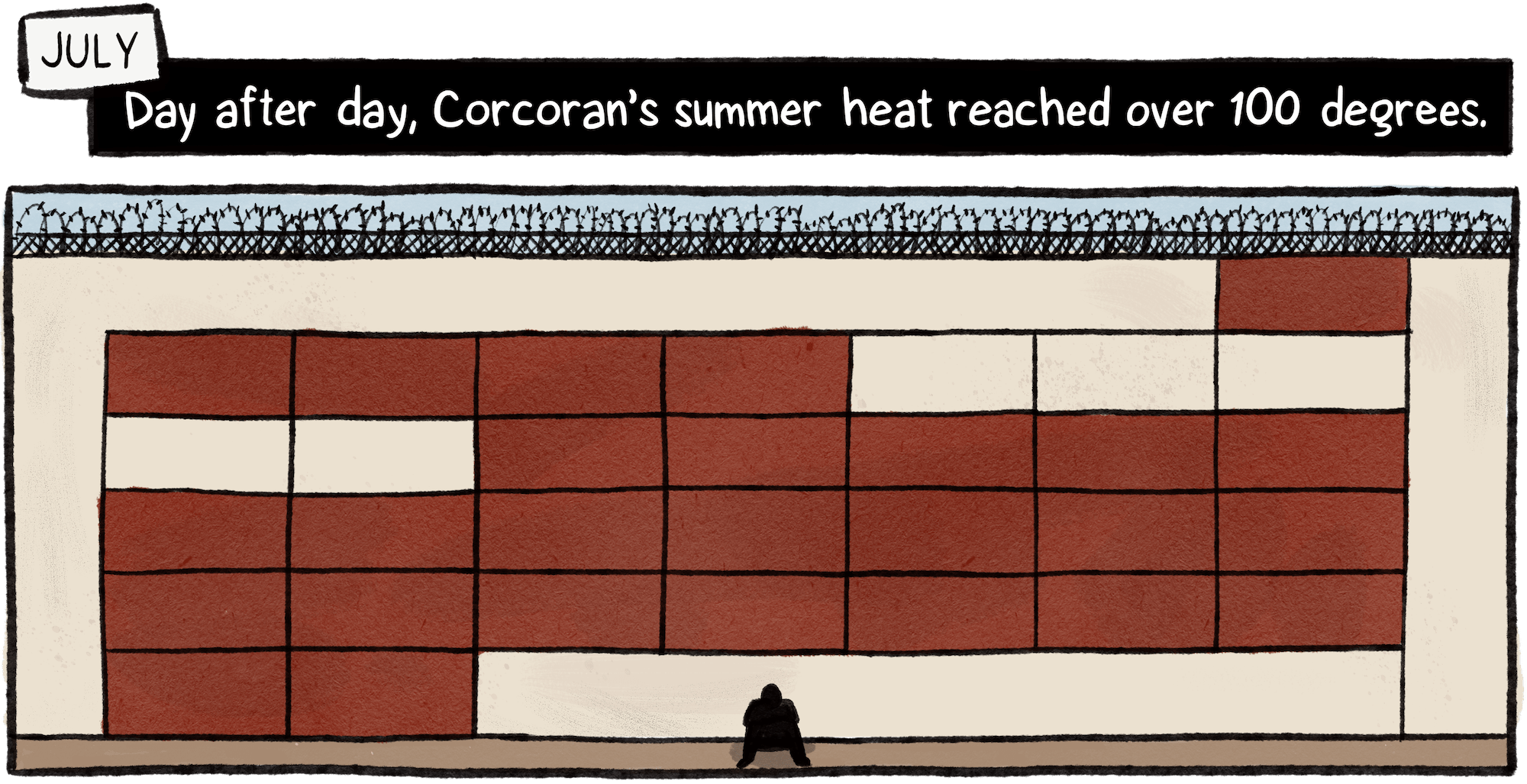

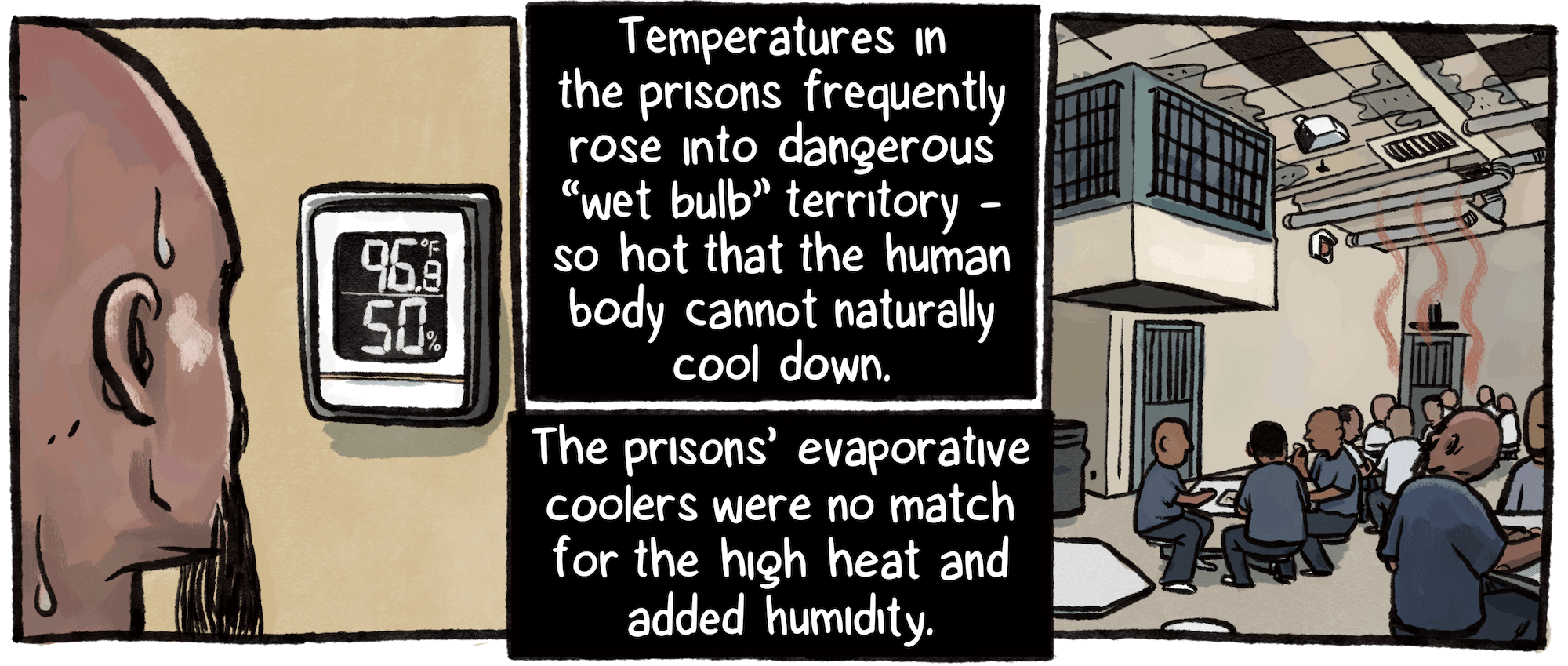

Daily temperatures, National Weather Service station in Hanford, California.

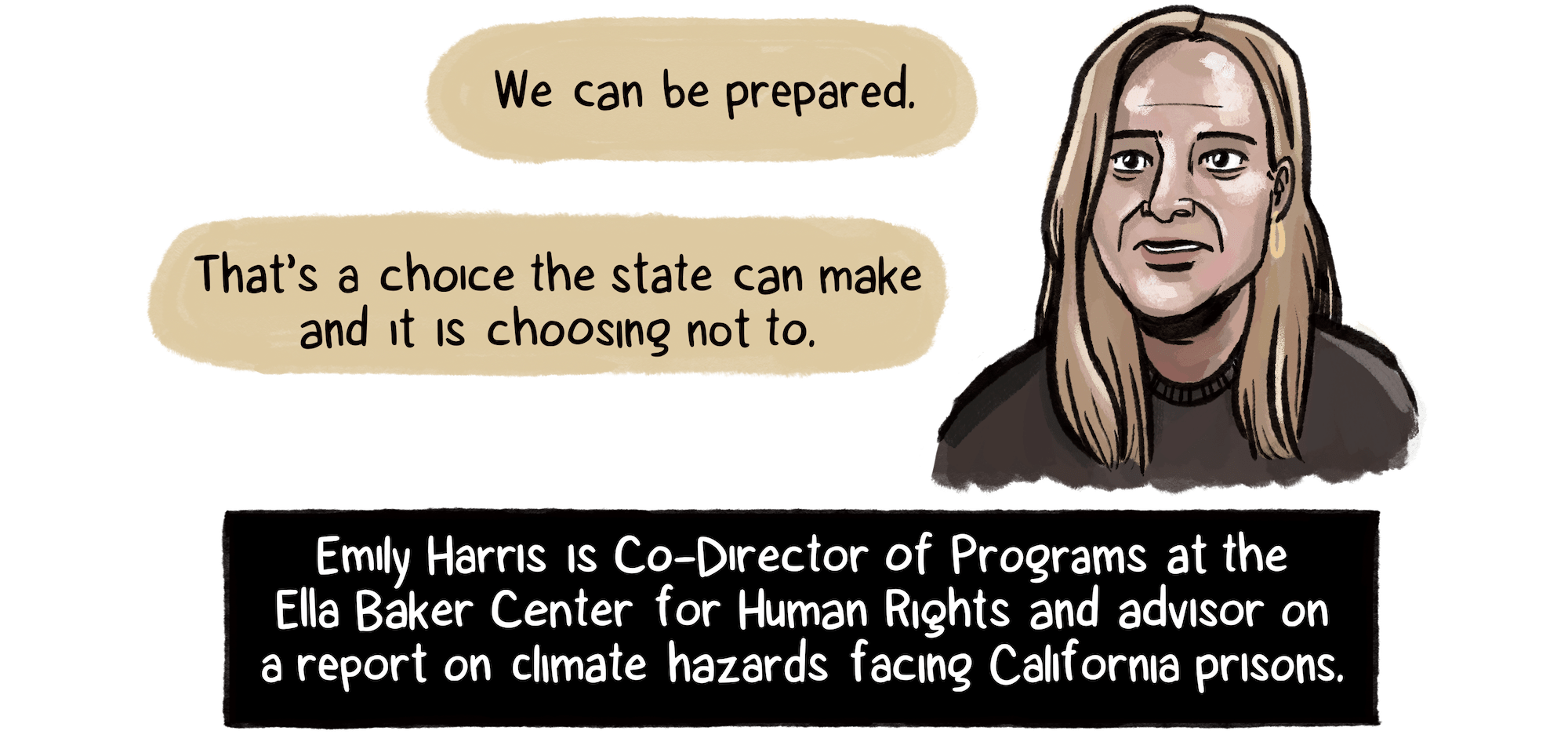

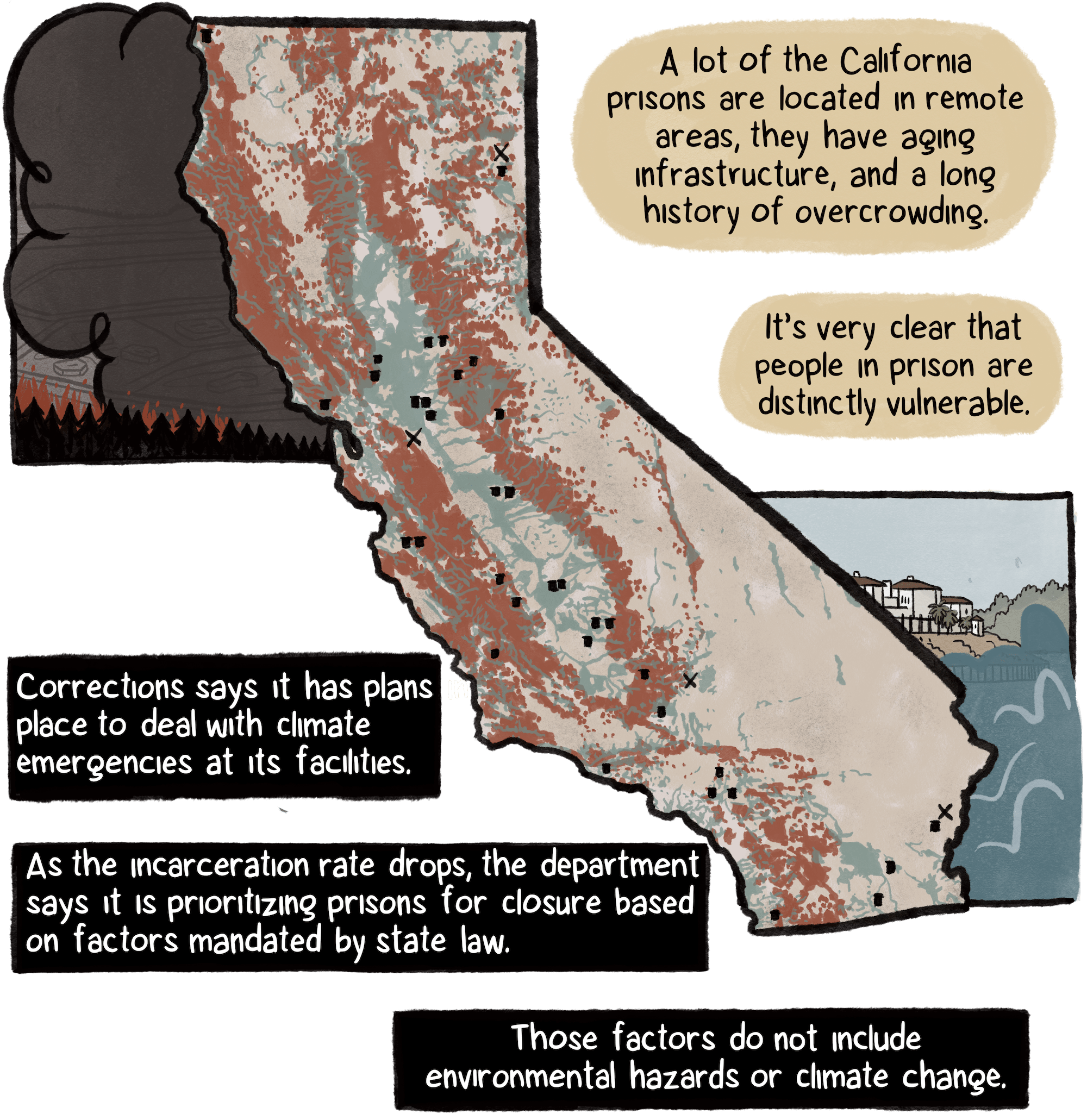

Fire risk depicted is sourced from CalFire 2023 maps; floodplains sourced from FEMA; prison locations, with “X” marking facilities being closed or in process of being closed, California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation.

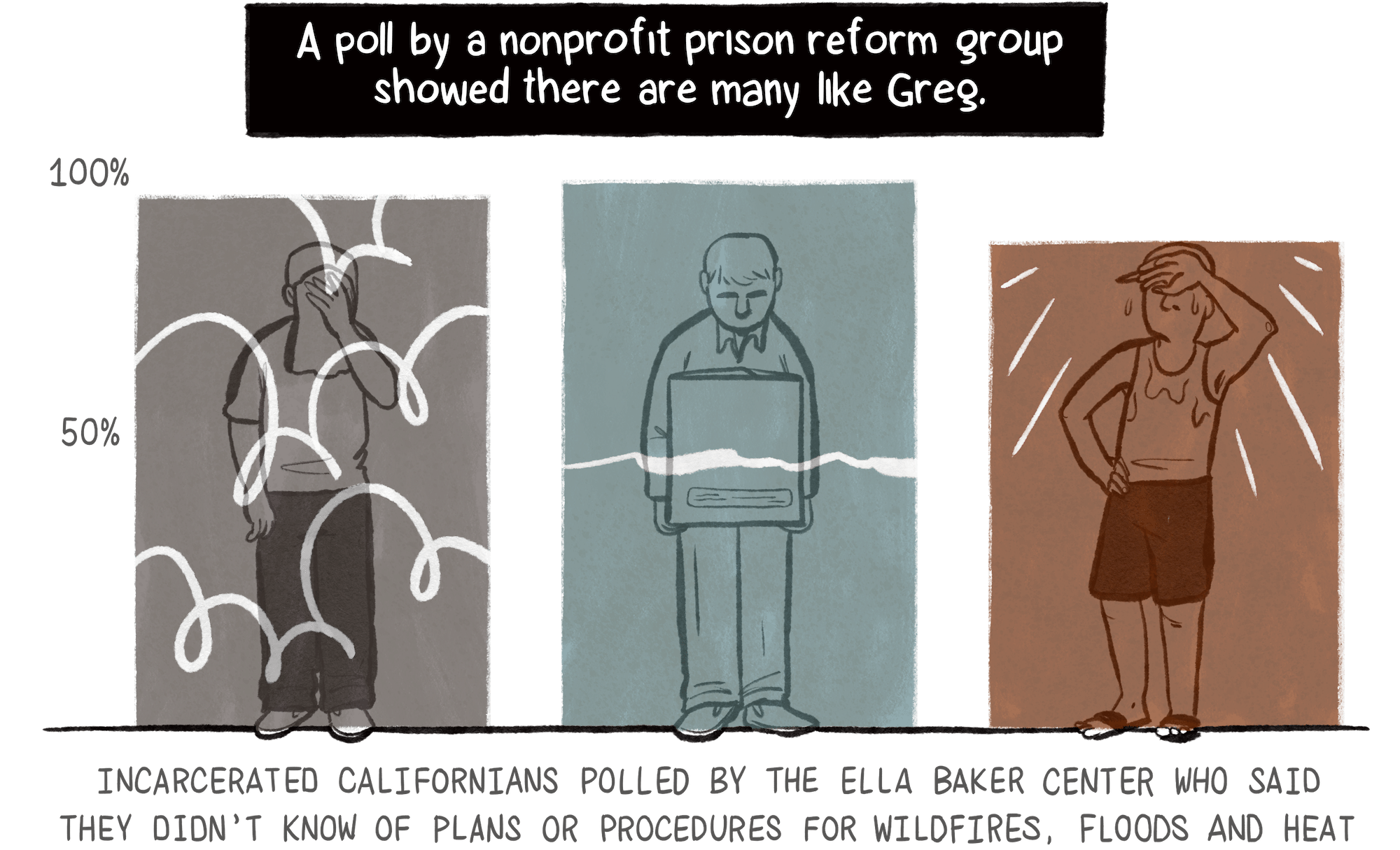

“Overlapping Crises: Climate Disaster Susceptibility and Incarceration” study published in 2022, based on data from FEMA and The Marshall Project.

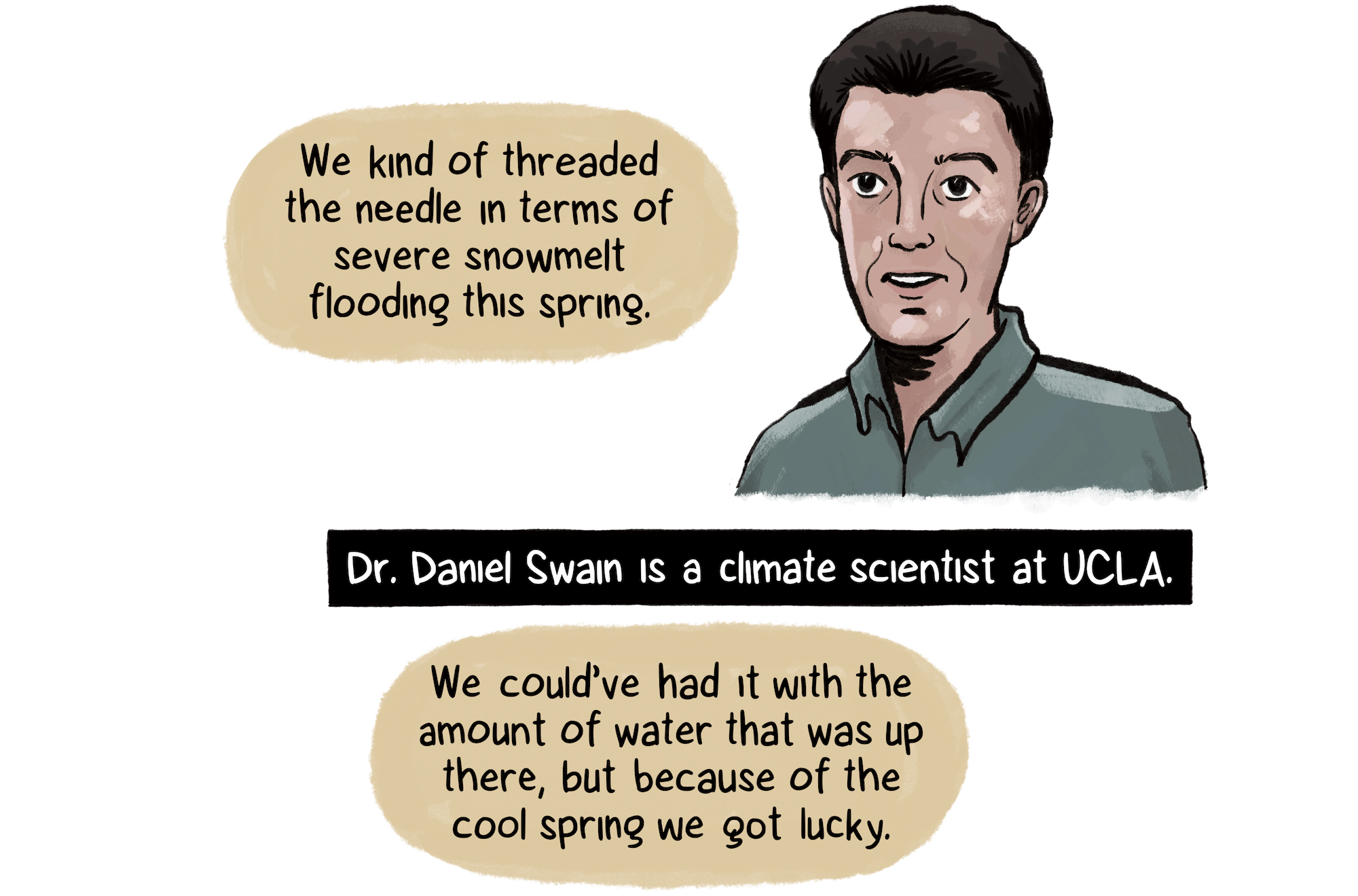

Climate scientist Daniel Swain “office hours” on YouTube, July 10, 2023.