“It felt all too real,” Siwatu-Salama Ra said from her home in Detroit, Michigan. Her lifelong struggles against two injustices plaguing her community — pollution and incarceration — had become fused in a surreal way.

Three years ago, Ra, a world-renowned environmental justice organizer, lay shackled to a hospital bed. Since her childhood, she had followed in the footsteps of her mother, Rhonda Anderson, fighting for environmental justice in her neighborhood — a commitment that led to her representing her city during the 2015 United Nations climate talks in France. But in 2018, Ra, pregnant with her second child, was sentenced to prison for waving an unloaded gun at someone during a dispute.

It was there, facing the prospect of giving birth in a women’s correctional facility outside Detroit, that she learned a new jail was being built to incarcerate her son’s generation, too. This time it would sit in the shadow of the largest trash incinerator in Michigan, and one of the largest in the country.

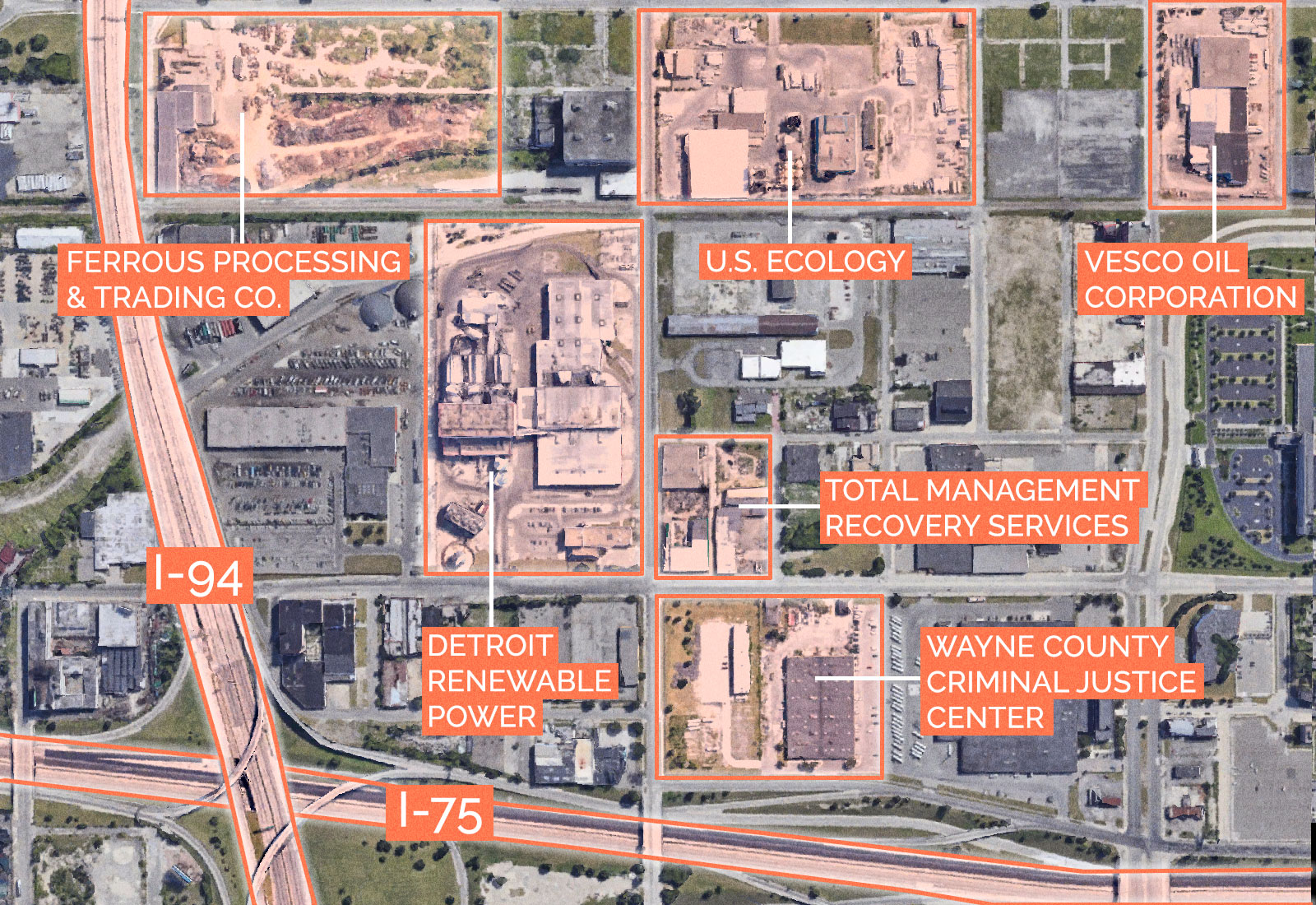

For three decades, Detroit Renewable Power had burned 3,000 tons of trash every day, emitting dangerous levels of nitrogen oxide, sulfur dioxide, carbon monoxide, and lead into the atmosphere, contaminating surrounding neighborhoods. Ra had spent years fighting to close the toxic site. Between 2013 and 2018, the incinerator racked up more than 750 citations for exceeding pollution emissions standards from the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality, or MDEQ. And, according to a local environmental law center, the incinerator violated the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency’s Clean Air Act over a hundred times, as well. Data from the EPA and MDEQ shows that the facility is located in one of Wayne County’s worst neighborhoods for air pollution — a community that is also 76 percent people of color and 71 percent low-income.

After being released, Ra and her colleagues succeeded in getting the incinerator shut down in 2019. The closure doesn’t completely eliminate the environmental threat, however: Studies have shown that contaminants emitted during waste incineration have the ability to infiltrate surrounding soil and groundwater, with impacts that persist for years even after a site is closed. Now, Detroit officials say a new jail complex is needed to address safety concerns in the city’s aging jails, as well as save on maintenance costs. But the city’s plan to construct the Wayne County Criminal Justice Center across the street from the old Detroit Renewable Power incinerator will force up to 2,400 incarcerated people to live in close proximity to the facility’s toxic legacy.

While trash is no longer being burned on-site, Detroit Renewable Power is still operating as a solid waste transfer station, taking in 1,000 tons of waste per day. Transfer waste stations are known to emit odors, cause noise, attract rodents, and cause air emissions both from unloading dry and dusty waste and increased traffic in the immediate neighborhood.

Down the street from the new jail site, just beyond the recently shuttered incinerator, is a hazardous waste treatment plant known to fill the air with a “rotting fish” smell, which over the past six years has itself received more than 20 pollution violations from the MDEQ, now called the Michigan Department of Environment, Great Lakes, and Energy. The waste treatment plant’s violations are primarily for pungent odors released into the neighborhood, but also for dust and soot emissions beyond state limits. Local residents say the emissions often make simply being outside unbearable. The jail site is also right next to I-75, a major highway, adding another source of noise and air pollution that inmates will be exposed to.

Construction of the Wayne County Criminal Justice Center, located off East Warren Avenue, is expected to be completed in 2022.

“Living in Detroit has given me a deep understanding that fights against the prison system and police are also fights against poverty and pollution,” Ra told Grist.

The close ties between incarceration and pollution seen in Detroit are replicated across the United States. A recent Grist analysis found that the nation’s three largest jail systems — Los Angeles, New York, and Chicago — have facilities disproportionately located in areas where there are elevated risks for pollution-related cancer, respiratory hazards, diesel pollution exposure, and proximity to toxic wastewater and hazardous waste. According to the EPA, those incarcerated within the new Wayne County Criminal Justice Center will be exposed to more diesel pollution and situated closer to hazardous waste than 90 percent of the country.

“Detroit doesn’t deserve to have a new jail built,” Ra said. “But this is what the prison industrial complex does: A new jail right in front of our faces, right across from the busiest highway in the city, next to what was one of the largest incinerators in the world, and of course down the street from an elementary school.”

The jail’s location on Detroit’s east side within a heavily polluted area wasn’t in the original plans. The project, which first got underway in 2011, was initially slated to be built in downtown Detroit, close to public transit. But after the city ran over-budget on the jail, construction paused. Officials made a deal with Dan Gilbert, co-founder of Quicken Loans, a company accused of fraudulent lending, and founder of Bedrock, a real estate business (both of which fall under Gilbert’s parent company, Rock Venture, which includes over 100 other affiliated businesses). The deal was that Gilbert would receive the original downtown jail site in return for providing funding to continue the project at a new location on Detroit’s east side, and that Bedrock would manage the construction of the facility.

This arrangement underscores the way that environmental and criminal justice have become entangled in the new Wayne County Criminal Justice Center: It’s being funded in part by a private investor, Gilbert, who has been charged with gentrifying Detroit — the Blackest large city in America — and displacing residents in the process, as apartment buildings across the city were forcibly vacated for redevelopment. “Never before has a private entity held so much influence in a major American city as Rock Ventures holds in Detroit,” Business Insider declared in 2018, “and no one in the private sector is as powerful as Gilbert.”

According to city officials, the jail will save taxpayers money in the long run and is needed to improve safety for those incarcerated. The new complex will replace three existing prison facilities that are spread across the city, a setup that requires inmates be transported from the jail to the courtroom for every legal appearance. The new centralized Wayne County jail will have a court on-site so that those awaiting trial will walk to court, rather than being driven. From the consolidation of the buildings and the resulting decrease in building maintenance and staffing costs, the new jail is expected to save taxpayers $10 million to $20 million annually.

Additionally, the aging buildings have been plagued by safety concerns stemming from issues like malfunctioning heating and air conditioning, as well as deteriorating ceilings and plumbing leaks. In the city’s view, it’s a humane and cost-effective investment. (One estimate, however, indicates that it would cost the county a total of just $18 million to $22 million to do major repairs on the existing jails, compared to almost $600 million to build the new complex.)

Environmental justice organizers argue the money could be better spent elsewhere. “Instead of putting forward hundreds of millions of dollars into prisons, we should be putting hundreds of millions of dollars into schools,” said Michelle Martinez, executive director of the nonprofit Michigan Environmental Justice Coalition. Detroit’s public schools are notorious for environmental health hazards like periodically unsafe drinking water, as well as mold and heating and cooling issues.

A new distribution utility plant will also be built to service the new jail — another $35 million the county will pay for. The plant will get its power from DTE Energy’s mix of energy sources, nearly half of which comes from coal, 21 percent from nuclear, and 17 percent from natural gas. “A jail and a [utility] plant are two shining examples of the kind of future that we don’t need,” said Martinez. “We should be moving away from fossil fuels at all costs.”

The project’s long, convoluted journey to fruition illuminates the uneasiness that many Detroiters feel around the new jail facility.

With Detroit’s aging jails’ maintenance costs rising, the Wayne County Commission secured $300 million in 2010 to build a new, centralized jail in downtown Detroit. Construction began just a year later. But within two years, work on the project came to a halt when Detroit hit financial troubles and filed for bankruptcy, facing $18 billion in debt. At that point, Wayne County had already spent more than $120 million on the half-built jail. The project then sat on hold for the next six years, costing Detroit taxpayers $1.2 million each month in service costs, a storage space lease, and interest and principal payments on the bonds.

In 2018, Gilbert and Wayne County struck a deal: Gilbert would receive the downtown site of the half-built jail for $21.3 million, as well as several other nearby plots for free (a total of 13 acres), in exchange for paying at least $153 million to finance the building of the jail at a different location in east Detroit, and for his own company, Rock Ventures, to actually construct the new facility.

Work on the east side location began in 2019. The project is now halfway done. The $533 million dollar facility, already over budget by $40 million, will house the sheriff’s office, a 2,200-bed adult jail, a 160-bed juvenile center, the circuit court, and the county prosecutor’s office. Over the last few years, Detroit residents have protested the new jail and its role in handing Gilbert more land in central Detroit to add to his more than 100 other downtown properties.

Construction continues on a new jail in Wayne County, Michigan (left), as seen in 2021. The new facility is located in one of Wayne County’s worst neighborhoods for air pollution — near a recently shuttered trash incinerator (right) whose toxic legacy, activsits say, continues to plague the area. Photos by Grist / Jena Brooker

The city agreed to move the jail because they needed Gilbert’s help financing the project — without which finishing the complex would’ve been “seriously difficult” and any other option would have been “extraordinarily more expensive,” Wayne County Commissioner Timothy Killeen told MLive. A local real estate expert, Colliers International Inc., estimated the value of the properties Gilbert obtained in the deal to be worth between $61 million and $84 million, if the properties were to be leveled and used for parking. At the new jail, Gilbert will receive up to $30 million in parking revenue as a part of the deal.

Detroit residents, community leaders, and environmentalists have raised concerns about the new location of the jail since its announcement, citing its proximity to a hotbed of industrial pollution, taxpayers taking on additional debt to finance the jail, and the inconvenience for visitors and criminal justice officials since the District Court will still be located downtown.

Despite multiple interview requests to the Wayne County Executive Office and Wayne County Commissioners, no one from the county was able to confirm whether or not an environmental impact statement or assessment was conducted before building the jail.

The jail is just one of several deals between Gilbert, the city, and the state of Michigan that local residents have called into question.

In one instance, the city’s Downtown Development Authority sold Rock Ventures a downtown land parcel for just $1. The Michigan Strategic Fund then approved $618 million in tax incentives for Rock Ventures for multi-use downtown development on the property. Michigan’s largest commercial mortgage banking firm, Bernard Financial Group, said the project couldn’t have happened without the tax incentives.

An investigation by The Detroit News found that Gilbert-owned Quicken Loans, which is headquartered in Detroit, had the fifth-highest number of mortgages that ended in foreclosure in the city between 2005 and 2015. Half of those properties are now blighted. In 2015, the federal government sued the company for approving hundreds of mortgages that didn’t meet federal standards. (Quicken ultimately agreed to a $32.5 million settlement of the suit without admitting wrongdoing.)

Rock Ventures and Gilbert declined to comment on the record about why Rock Ventures got involved with the publicly funded project or respond to claims that Rock Ventures has contributed to gentrification in Detroit. They pointed Grist toward a $500 million investment by the Gilbert Family Foundation in Detroit as an example of Gilbert’s commitment to the city. The first phase of this investment initiative, $15 million, will pay off property tax debt owed by 20,000 low-income homeowners.

Casey Rocheteau, communications manager at the Detroit Justice Center, a nonprofit law firm that unsuccessfully sued the county to block construction of the jail in 2018, told Grist that the placement of the facility in an industrial area was a deliberate move with effects on already marginalized communities.

“They replaced the incinerator with this carceral facility, so instead of this area just being affected by literal pollution, now people [also] have to deal with this emotional, mental, and psychological pollution caused by the jail,” they said. Rocheteau says the placement of the jail next to the city’s main freeway creates “a public spectacle of making sure people know [the county] is keeping the ‘criminal elements’ away from them, while they enjoy downtown or go to a Tigers game.”

Although the new jail has 671 fewer beds than the county’s current facilities, Wayne County’s incarcerated population has been on a downtrend for years, which advocates say highlights the need for even smaller facilities. In February 2020, before the start of the coronavirus pandemic, 1,400 people were incarcerated in Wayne County, with that number dropping to 800 as the coronavirus began its spread in April, prompting the county to release everyone except those charged with felonies.

According to an analysis by the Vera Institute of Justice, a national research and activism lab that advocated for the mass release of Wayne County jail detainees at the height of the pandemic, more than half of all Wayne County jail bookings in 2018 and 2019 were for lower-level criminal and civil offenses. Charges related to petty offenses like suspended licenses, registrations, or failing to have car insurance were the most common charges for people locked inside the jail during that time. More than half of the people incarcerated inside the county’s jails were detained pre-trial, meaning they were unable to afford bail and subsequently left incarcerated without ever being convicted of a crime.

Rocheteau says these statistics underscore the hasty decision by the county to build the new justice complex when jail populations could be lowered by investing in social services and toxic remediation for communities living amongst industrial waste, rather than in a new jail. Several studies show that communities with better-maintained environments and public health investments are less likely to have high incarceration rates. Detroit currently spends 10 times more on police than it does on health care and public health programs. In 2019, Wayne County allocated just $10 million out of its $1.5 billion budget for youth services, community development, and environmental programs combined, compared to $311 million it spent on courts, jails, and the county sheriff.

“There is the ability to drastically reduce the population of people in the Wayne County jail system while maintaining public safety and investing in the key concerns that would make our communities safe from all forms of harm, environmental harm included,” Rocheteau said.

Since 2018, the No New Jails Detroit coalition — of which both the Detroit Justice Center and Ra’s organization, the Freedom Team, are members — has led a divestment campaign in attempts to block the construction of the Wayne County Criminal Justice Center. Instead of spending money on the new justice complex, the group has instead outlined investments that would be possible using the same money allocated for the jail: 30 new restorative justice centers, renovating and modernizing all Detroit public schools, or housing every homeless person in Detroit. But at this point, with the new justice center nearing completion, it’s about continuing the “generational fight,” according to Ra.

“This is going to be the work of our children’s children. We’re planting the seeds to show that our communities deserve better, that majority-Black Detroit deserves better.” Fighting the construction of the jail, although unsuccessful in one sense, was a victory for the organizers of Detroit, Ra says. Community leaders are beginning to connect all aspects of public health and the environment at the center of struggles for justice — and will continue to do so.

“Detroit will be one of those cities that will lead our fight for freedom and survival — connecting the environmental justice movement, decarceration, defunding the police, clean water, and better food for everyone,” she said. “Our perspective from fighting for freedom with the jail will forever be applied to all of the ways that we envision ourselves and what it means to be healthy and free.”