The food movement has done a great job winning the hearts and minds of eaters, but not such a great job moving the economic and political levers that shape our food system. For that reason, it can seem as if nothing ever changes. If you’re watching the high-profile debates (cough, GMOs), that’s true: The same people make the same arguments over and over, resulting in a robust stalemate.

But there is real change happening in areas that I contend are even more important than the most popular and highly covered food fights. Here’s my year-end list of ways the food system changed for the better (mostly) in 2014, along with some predictions for next year.

Deforestation

This has been a banner year for the campaign against deforestation.

There has already been real and sustained progress in protecting the Brazilian Amazon over the last decade, even while food production in Brazil increased. In 2014, we saw commitments locked into place that could take that success global.

Activists have focused efforts on palm oil production, currently the most extreme driver of deforestation. And in 2014 (OK, it really got rolling in December 2013) they succeeded in getting all the major traders of palm oil to commit to buying only from farmers who are doing things right.

At the U.N. Climate Summit in New York, ag commodity trader Cargill pledged to go beyond palm oil and protect forests wherever its buying power gives it influence.

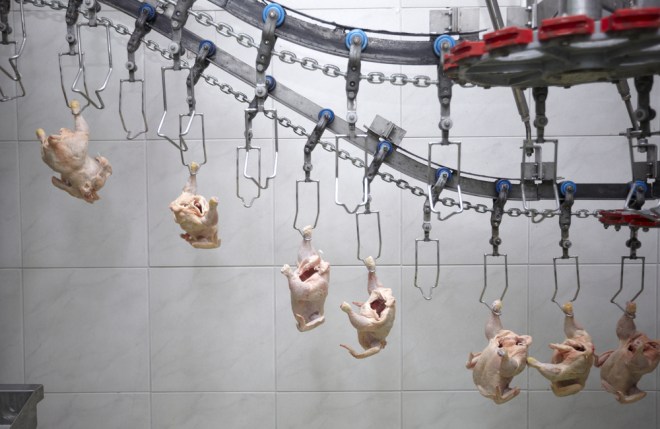

Antibiotics in agriculture

The Food and Drug Administration recently issued new rules for antibiotic use in agriculture, and it’s still unclear how much impact those will have. But the industry has already begun to change. In September, the poultry company Perdue announced that it was curtailing its use of antibiotics and eliminating the drugs from hatcheries. The biggest chicken company in the U.S., Tyson, followed suit in October. And then in December, six big cities allied to announce they would only buy chicken raised without antibiotics for their school lunches.

You can see the snowball starting to roll on antibiotics, and it should gain mass in 2015.

Fertilizer pollution

Oftentimes you can’t see pollution, but when it makes green slime grow over your lakes and drinking water sources, you’re likely to take notice. In 2014, toxic algae bloomed in the Great Lakes; pollution was so bad in Toledo, Ohio, that the city went without water for three days; and the Des Moines Water Works threatened to sue the state of Iowa over high levels of nutrients in the drinking water.

With all this in the news, farmers are realizing that they are going to have to clean up their act, and they are making improvements — installing filters and reducing the amount of fertilizer they apply. When it comes to public policy, farmers’ groups are still dead set against regulation. But individual farmers, at least the smart ones, see that change is inevitable. And ultimately, the change will be good for them: No one wants to buy a fertilizer only to see it wash downstream.

Pesticide pollution

If you can avoid the green slime, at least there’s less dangerous pesticide in the water. Two decades ago, 17 percent of streams in the U.S. had hazardous levels of pesticides. But in the last decade there was just one single stream monitored by the U.S. Geological Survey that had dangerous levels of chemicals.

There’s still enough pesticides to cause problems for non-human aquatic critters, though, and while farmers have done a better job, there are still lots of pesticides from city dwellers going into waterways.

Investments in alternatives

The farm bill, which passed at the beginning of the year, included a lot of money to test out new ideas and alternatives. There’s $100 million for organic research and training, another $100 million to help beginning farmers, and $800 million for research on non-mainstream crops. And that’s just the beginning. The USDA is funding local food initiatives, and programs to help school lunches improve. There’s money available to help connect struggling families to healthier food.

Of course, all this adds up to less than 1 percent of the farm bill. Some 80 percent goes to food stamps, and 8 percent to crop insurance. But it’s still much more than these innovative ag projects have gotten in the past, and it’s enough money to allow good ideas to germinate.

Bales of kale

OK, so this doesn’t have anything to do with policy, but I’m praying that kale peaked this year. Pretty much every story in the New Yorker’s food issue mentioned kale, and I’m just having a hard time keeping up. As a food writer, I feel it’s my duty to have a bowl of raw kale delivered to my desk every morning, and I force myself to finish it before I go to bed. I really don’t think I could handle an increase.

Surely 2014 was the year of kale. But look at this chart, showing word-usage frequency in Google Books over the years. What, I want to know, happened in 1944?

I think we’ll see more of the same in 2015. The fight over GMOs, and over conventional versus organic, will only grow louder. But underneath the controversy I think we’ll start to see more and more people on the ground using tools from both sides.

You can see this already in announcements from the U.N.’s Food and Agriculture Organization. The FAO has begun trumpeting low-input, eco-friendly farming. But the examples the FAO chooses are low-input, not no-input. For example: “In southern India, site-specific nutrient management, which matches nitrogen inputs to plants’ real needs, has reduced fertilizer applications and costs, while increasing wheat yields by 40 percent.” There’s a recognition that nitrogen fertilizer has a place, but it should be a small place.

Nonpartisan organizations like the FAO are trying to find things that work. But that kind of pragmatism rarely turns up in the high-profile fights over technologies.

Farmers are powerfully attracted to what actually works, so I suspect that the pragmatists will lead on the ground, even as the public debate intensifies. In other words, more polarization in rhetoric, and more consilience in practice.