Will the food movement ever really turn political? This question has been much discussed of late, thanks in part to Michael Pollan’s recent New York Times Magazine op-ed on California’s GMO labeling referendum (which I discussed here).

And yes, as Pollan argued recently, whether or not California’s Prop 37 passes will be one sign that the movement has come of age (i.e. eaters “voting with votes, not just forks”). But winning one election in one state, however large and trendsetting, would be just the beginning. Every good political movement identifies its allies and its enemies in an attempt to breed more of the former and weed out the latter.

Today — on Food Day — we’re seeing signs that the food movement may in fact be starting to grow up. And like learning how to balance a checkbook or making sure bills get paid on time, some of the most crucial rites of passage can seem more like chores than privileges.

So it is with a new organization called Food Policy Action, a lobbying group that intends to grade members of Congress on their voting records on food-related legislation. The group’s board of directors includes several big names in food: Stonyfield Farm’s co-founder Gary Hirshberg and the Humane Society of the United States’ CEO Wayne Pacelle, as well as leaders from Oxfam America, the Center for Science in the Public Interest, and the Environmental Working Group — and lest I forget, Top Chef’s head judge Tom Colicchio.

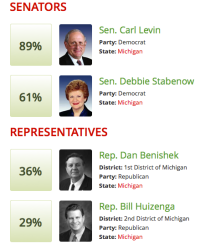

A screen grab from the Michigan page on the site (where Debbie Stabenow, head of the Senate Agriculture Committee, earns a barely passing grade). Find your members of Congress.

The Food Policy Action website will quickly become essential for anyone interested in food policy (just don’t all click the link at once now!). Like other food-related advocacy groups, it presents an overview of issues such as jobs, nutrition, sustainability, and hunger as they relate to food.

But the meat of the effort — and the thing that distinguishes it from other groups — has to do with the sometimes mind-numbing but essential subject of federal legislation. Food Policy Action has collected all the pending federal legislation and agency rulemaking with a bearing on the food system in one place. The site displays roll call votes for all food-related bills from the 112th Congress (i.e. bills voted on from January 2011 until now) with the outcomes color-coded red or green depending on whether FPA supports or opposes the bill in question.

For example, on Sen. Mike Johanns’ (R-Neb.) amendment to the Senate Farm Bill that would keep the EPA from monitoring the pollution of large livestock operations via airplanes, the “yea” votes are red, since Food Policy Action opposed that piece of legislation. Meanwhile, the “yea” votes for Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand’s (D-N.Y.) amendment to the Senate Farm Bill, which would have restored $4.5 billion in cuts to the food stamps program, were coded green.

Many interest groups before it have taken this tactic, but this is the first time a food group has taken a “scorecard” approach. Each legislator’s “score” is searchable by name and zip code, and the information can also be sorted by state, party, chamber, and score.

The legislators who come up short receive the shameful label of “Food Policy Failure,” like Rep. Steve Stivers (R-Ohio): 0 percent; Rep. Diane Black (R-Tenn.): 8 percent; and Sen. Roy Blount (R-Mont.): 6 percent. You’d think it would be helpful to highlight “Food Policy Heroes” as well (you know what they say about carrots vs. sticks). But it’s not hard to find folks with good scorecards on the site. Sen. Barbara Boxer (D-Calif.), for instance, earned 100 percent, according to the scorecard methodology (as did about 40 other Democrats, although it’s worth noting that legislators don’t seem to get penalized for skipping a food-related vote, so 100 doesn’t mean a “yea” vote on every food-related bill or amendment).

While it can’t compare to other prime examples of the internet’s unmatched ability to aggregate important information into one convenient package — I’m talking, of course, about sites like Binders Full of Women, Otters Who Look Like Benedict Cumberbatch, and Dog Shaming — this kind of infrastructure is absolutely vital to the food movement’s ability to become a political force. Indeed, Food Policy Action is explicitly trying to fill the gap Michael Pollan has noted.

A true movement must hold its politicians accountable. And you can’t do that unless you know what they’re up to. It’s the freedom to operate out of the limelight that gives lobbyists and corporations the chance to move legislation that’s less in the public interest than their own.

By putting all this information in one place — and weaving the many pieces of legislation that touch on the food system into a single narrative, as it were — Food Policy Action goes a little way toward helping advocates build a genuine movement. It’s not the last piece of the food politics puzzle, but it’s an important one nonetheless. So, go take the site for a spin. You may be shocked (or pleasantly surprised) by what you learn about your representatives.