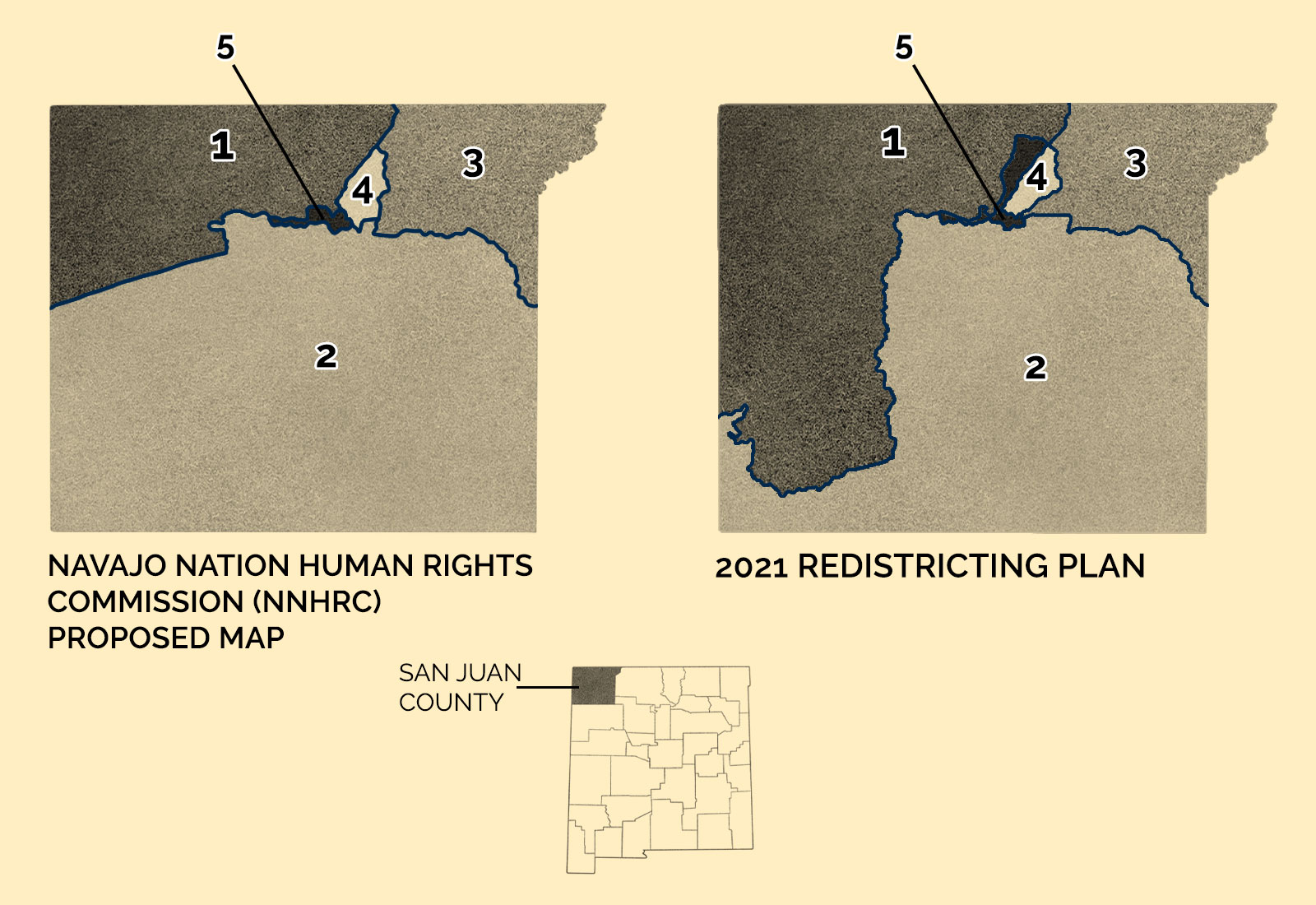

In February, the Navajo Nation sued San Juan County, New Mexico over its new redistricting plan. San Juan County, which stretches across a large swath of the Navajo reservation, has enough Indigenous voters to be a majority in two voting districts. The Navajo Nation’s lawsuit, however, argues that the county’s redistricting plan packs those voters into a single voting district, diluting the power of Indigenous people at the polls and violating the Voting Rights Act.

For Leonard Gorman, executive director of the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission (NNHRC), the stakes couldn’t be higher. Indigenous voters often have different priorities at the polls than their non-Indigenous counterparts, and less voting power means they are less likely to be represented by lawmakers on issues they care about. In particular, Gorman says, redistricting could impact Navajo people’s ability to deal with resource allocations, water quality and access, and land use – environmental issues important to Indigenous people in the area. “Redistricting affects every aspect of our lives,” he said.

Across the US, states are redrawing the borders of congressional and legislative districts based on population counts and changes recorded in the 2020 Census. The new boundaries will apply to federal, state, and local elections for the next ten years and New Mexico is one of several states where Indigenous voters have serious concerns that redistricting plans will limit their ability to protect their interests. Now, tribal leaders and experts say that this once-a-decade redistricting process may become a lost opportunity, resulting in another decade of disenfranchisement and lack of legislative advocacy, impacting everything from land and resource exploitation to protections for water.

“Rather than working on understanding the issues that are important to Native voters, some elected officials would rather suppress the Native vote,” said Keaton Sunchild, political director for Western Native Voice. “We fear that these groups are just getting started.”

Based on the 2020 Census, the state of Montana will gain a congressional seat, giving it two for the first time in decades. Montana’s plan divides the state into an eastern and western district, raising alarms for several Indigenous nations and groups in the state. Two reservations are in the western district, while the other five are in the eastern district. Sunchild, a member of the Chippewa Cree Tribe, says that the newly redistricted map dilutes the voices of Indigenous voters. “It really doesn’t put a lot of emphasis on the Native vote in either district. It makes it easy for candidates to ignore Native voters and Native priorities,” he said.

Sunchild says that when he canvasses Indigenous voters in the state, their main concerns are natural resource production, protecting reservation lands, and hunting and fishing rights. The new map, he says, makes it harder for voters to get those concerns heard at the legislative level.

But Maylinn Smith, chair of the state districting commission, says that every effort was made to group reservations together. Smith, who was appointed by the state supreme court last year, was a tribal law professor at the University of Montana and has also worked within several tribes’ legal systems. “I’m incredibly sensitive to tribal sovereignty issues since I have spent my entire life doing Indian law. I recognize those interests,” she said. However, based on the state’s geography, Smith added there was no way to group more reservations together.

Patrick Yawakie, political director of Indigenous Vote, an advocacy organization that promotes voting in Indian Country, is enrolled in the Zuni Pueblo Tribe and is Turtle Mountain Anishinaabe and White Bear Nakota & Cree. He says that Indigenous representation is especially important at this moment, following what he describes as one of the worst legislative sessions in Montana history for Indigenous issues. As an example of state law that threatens tribal environmental interests, Yawakie points to a bill that sets criminal penalties for people protesting pipelines and other infrastructure projects.

“We viewed this as a direct attack on our communities and our first amendment rights to voice our concerns against projects that hurt the environment,” Yawakie said about the bill, which he sees as a response to Indigenous activism against the DAPL, KXL, and Line 3 pipelines.

In 2020, the Native American Rights Fund (NARF) released a 176-page report that outlined the many challenges facing Native voters and candidates. The report described obstacles at every level of the electoral process, including redistricting, voter registration, casting ballots, and running for office. The report found that Indigenous voters have filed 94 lawsuits based on the 14th and 15th Amendments, and the Voting Rights Act, winning, or successfully settling, in 86. NARF has been working closely with tribal leaders in states, including New Mexico and Montana, and has released toolkits to help Indigenous communities advocate for themselves throughout the process.

The entire redistricting process relies on data that has already put Native voters at a disadvantage. A report from the US Census Bureau revealed that the 2020 Census undercounted Native Americans, both on and off reservation, as did the 2010 Census – a trend that could be corrected by working directly with tribes. Black and Hispanic people were also undercounted while white and Asian people were overcounted. In a statement, Fawn Sharp, President of the National Congress of American Indians, said that “These results confirm our worst fears” and called on federal agencies to work with tribes to ensure the undercount doesn’t lead to underfunding.

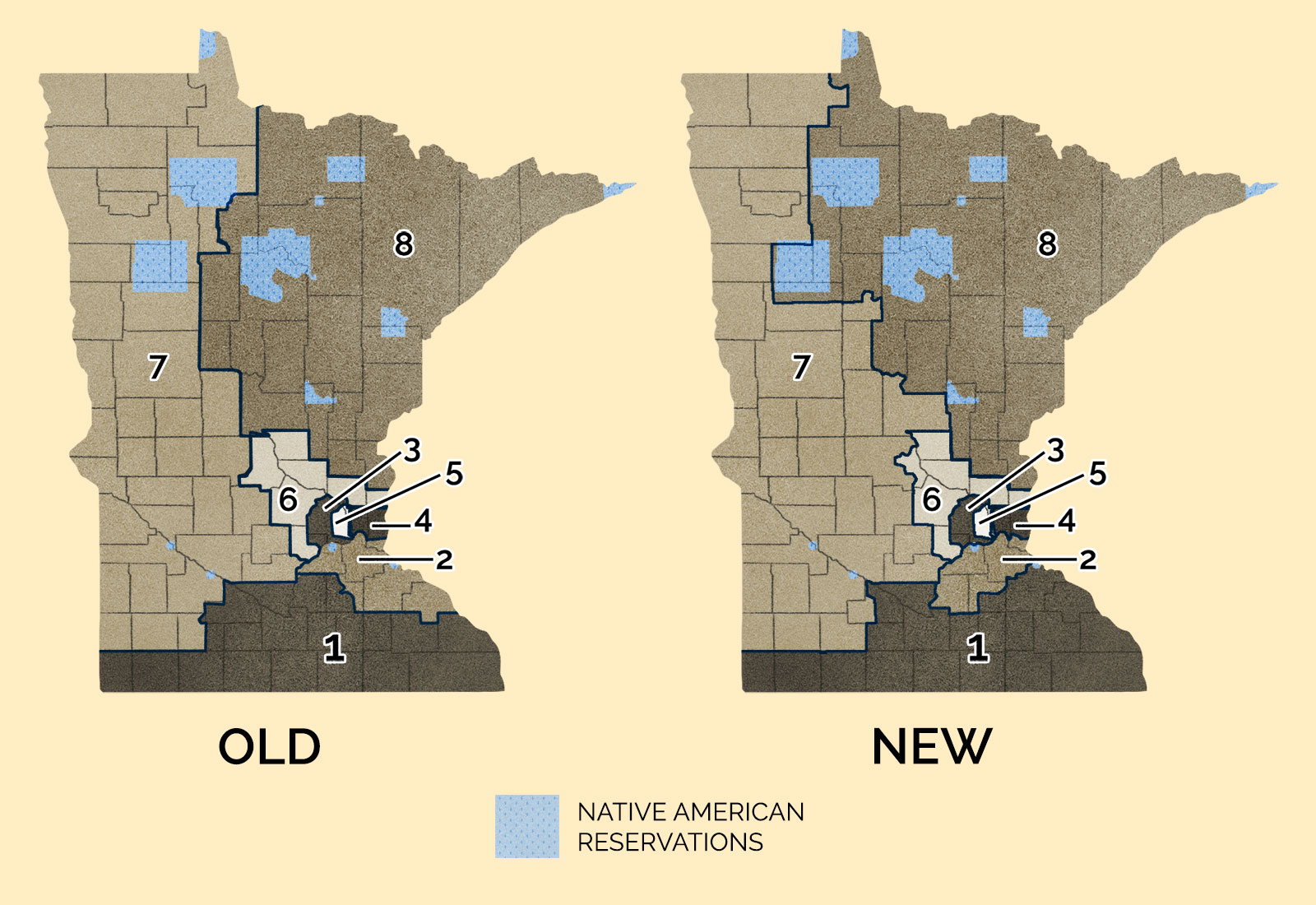

In Minnesota, Representative Jamie Becker-Finn, a Leech Lake Ojibwe descendant, says decades of work by tribal advocates have finally paid off in the state’s new redistricting maps. In February, the state redistricting panel, made up of five judges, announced the new map, which placed all seven Ojibwe reservations in the same congressional district for the first time. The map also grouped tribes within the same state legislative districts. Several Indigenous candidates have already announced their candidacy in the new districts.

“This change respects the sovereignty of the American Indian tribes and the request of tribal leaders and Minnesotans across the state to afford those tribes an opportunity to join their voices,” the panel wrote.

Although the new maps have drawn cautious optimism from a range of political parties, groups, and communities across the state, Common Cause Minnesota, a nonpartisan voter advocacy group that worked to increase representation for minority and disenfranchised communities, has expressed disappointment that the new maps did not emphasize communities of color as much as they hoped for.

Becker-Finn, who grew up on the Leech Lake reservation and represents a suburban district in the Twin Cities metropolitan area, says that the new map is a huge opportunity for Indigenous voters. Before, she says, they had little opportunity to advocate for environmental causes that impacted their communities.

The Line 3 pipeline project is one of the issues Becker-Finn thinks could be affected by the new districts. “We simply did not have the political power to stop it at the time. If our legislature better reflected the voices of Native folks, then maybe it would not have gone the way that it went,” she said.

Becker-Finn is hopeful about the opportunities created by the new districts, but acknowledges that progress will take both time and work. “This is an opportunity. It’s on us to do the work to make it as meaningful as it can be,” she said.

However, while tribes in Minnesota work to take advantage of redistricting, the Navajo Nation’s situation with regards to San Juan County is far more common. Tribes in Nevada, Oregon, and other states have expressed serious concern about redistricting, while other nations fight redistricting practices in court. In February, the Spirit Lake Tribe, the Turtle Mountain Band of Chippewa Indians, and individual voters sued the state of North Dakota over its redistricting map. The new plan, the lawsuit says, splinters Indigenous voters across multiple districts.

“It’s just another way of hindering our ability to vote,” said Douglas Yankton, Chairman of the Spirit Lake Tribe. “We are citizens of the state. We should have a voice.”

However, the Mandan, Hidatsa and Arikara Nation on the Fort Berthold reservation has expressed support for the North Dakota map, which places Fort Berthold in its own district instead of dividing it.

Leonard Gorman, executive director of the Navajo Nation Human Rights Commission, stresses that giving Indigenous voters the ability to advocate for their environmental concerns will benefit everyone, not just Indigenous communities.

“This is the time in which Indigenous peoples must have the floor,” he said.