The way people talk about our overheating planet has been getting pretty spicy. Bland, neutral-sounding phrases like global warming are out; evocative words like crisis and emergency are in. Some activists have argued that more urgent language will jolt people into realizing that climate change is already here, prompting a speedier effort to cut greenhouse gas emissions. As an opinion piece in the Guardian once put it: “Our planet is in crisis. But until we call it a crisis, no one will listen.”

New research, however, casts doubt on this premise. A study recently published in the journal Climatic Change is among the first to examine the effects of using climate crisis and climate emergency. It reported that reading these phrases “did not have any effect on public engagement,” measured in terms of whether the words had altered people’s emotions, their support for climate policy, or their belief that action could make a difference.

“We were pretty surprised that the terminology has such minimal effects,” said Lauren Feldman, a professor of media studies at Rutgers University and a coauthor of the study. Researchers found one instance where the stronger phrasing backfired: News organizations deploying climate emergency came across as slightly less trustworthy, perhaps because it could sound alarmist.

The overall takeaway is that journalists and climate advocates might be getting too hung up on specific words when the bigger picture is much more important, Feldman said. What makes an article resonate with people has more to do with its subject. News stories that emphasize taking action tend to make people feel hopeful. Articles that highlight solutions are also viewed as more credible, and people are less resistant to them. Consider a recent piece from the New York Times that explores how the Republican mayor of Carmel, Indiana, built 140 roundabouts in town, in part to cut down on the carbon emissions from cars waiting at stoplights.

On the other hand, news of disasters turns people off. “Focusing on the threat and negative impacts and the political conflicts surrounding climate change can be very immobilizing,” Feldman said. It’s worth noting, though, that behavior is complicated, and neither hope nor fear consistently inspire people to act on climate change.

There’s been a lot of thinking behind what to call the chaotic shifts unfolding on our planet. Scientists tend to prefer climate change over global warming because it captures a broader picture of what’s happening — not just hotter temperatures, but also changes in flooding, wind patterns, the oceans, and more. Conservative strategists also happened to like the phrase because it apparently sounded less scary than global warming. But some activists and scientists thought both expressions sounded like hollow understatements. They began adopting more colorful language, like climate chaos and global weirding. In 2019, the Guardian caused a stir when the publication announced that it would be dropping climate change for more “accurate” language: climate emergency, crisis, or breakdown.

The phrase climate crisis started popping up everywhere — headlines, TED talks, and in the U.S. Congress — and has recently strengthened its foothold, making it into the Oxford English Dictionary last month. The push behind climate emergency has taken a slightly different path, with proponents demanding that governments declare a state of emergency on climate. About 2,000 cities, town councils, and countries around the world have already done so.

At least two previous studies raised questions that climate crisis might not be working as intended. In 2013, researchers found that college students reading a passage about the climate crisis reported the lowest levels of concern about the overheating planet, whereas reading about climate disruption elicited the most. In 2020, researchers comparing the effects of the terms climate crisis and climate change on people in Taiwan found that the crisis framing backfired among those with a conservative outlook. Feldman’s research didn’t find any of these effects.

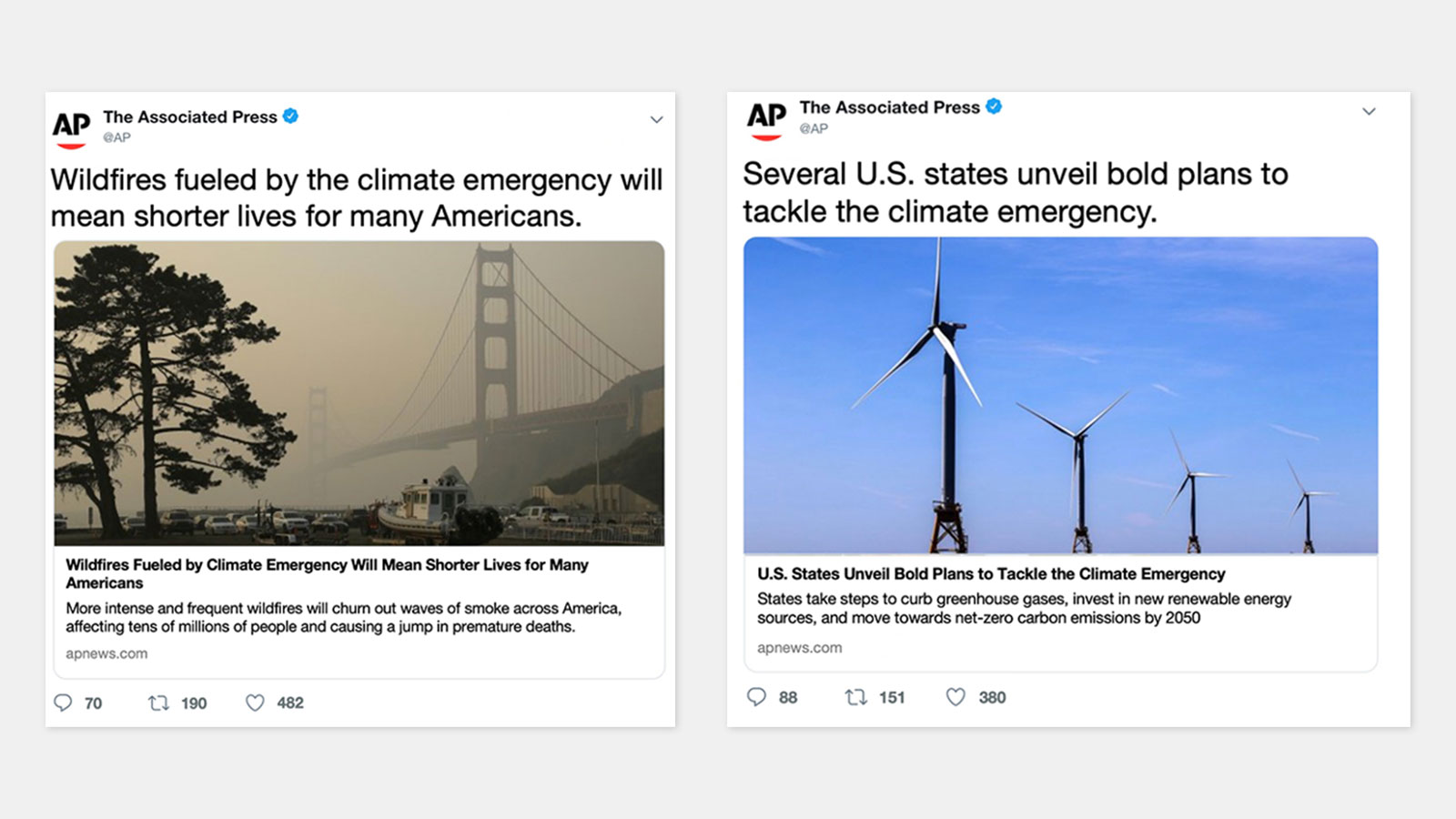

The new study, conducted last year, was meant to reflect how people actually get their news these days, skimming blurbs on social media but rarely clicking through to read the whole article. Feldman and a communication researcher from the University of Michigan rounded up more than 2,300 people online and showed them short news posts on Twitter — fake examples that swapped out the phrases climate crisis, climate emergency, or the old standby, climate change. Some of the tweets highlighted threats (wildfires, public health concerns), while others focused on responses (young people protesting, states unveiling climate plans). After reading the tweets, participants were asked to rate their emotions around climate change, their feelings about the media, their support for climate policies, and more.

The study offers a couple of reasons why the exact terminology didn’t end up mattering much. For starters, the tweets were short — longer exposure to these terms could make more of a difference. Another factor could be that these phrases are becoming more widespread, losing their initial surprise factor. One report found that climate crisis was 20 times more common this year than in 2018, and that climate emergency became 76 times more common over the same period. “It could just be that people aren’t noticing it, right?” Feldman said. “They’re just kind of lumping these different terms all together.”

These results, Feldman says, shouldn’t be taken to mean that anybody should stop saying climate emergency or similar terms. The words alone may be unlikely to prompt someone to get behind rapid climate action, but “that doesn’t mean that they’re not important in other ways,” Feldman said. The way she sees it, the new terminology reflects a broader shift: Journalists, politicians, and scientists are all talking about the climate as something deserving of immediate attention.