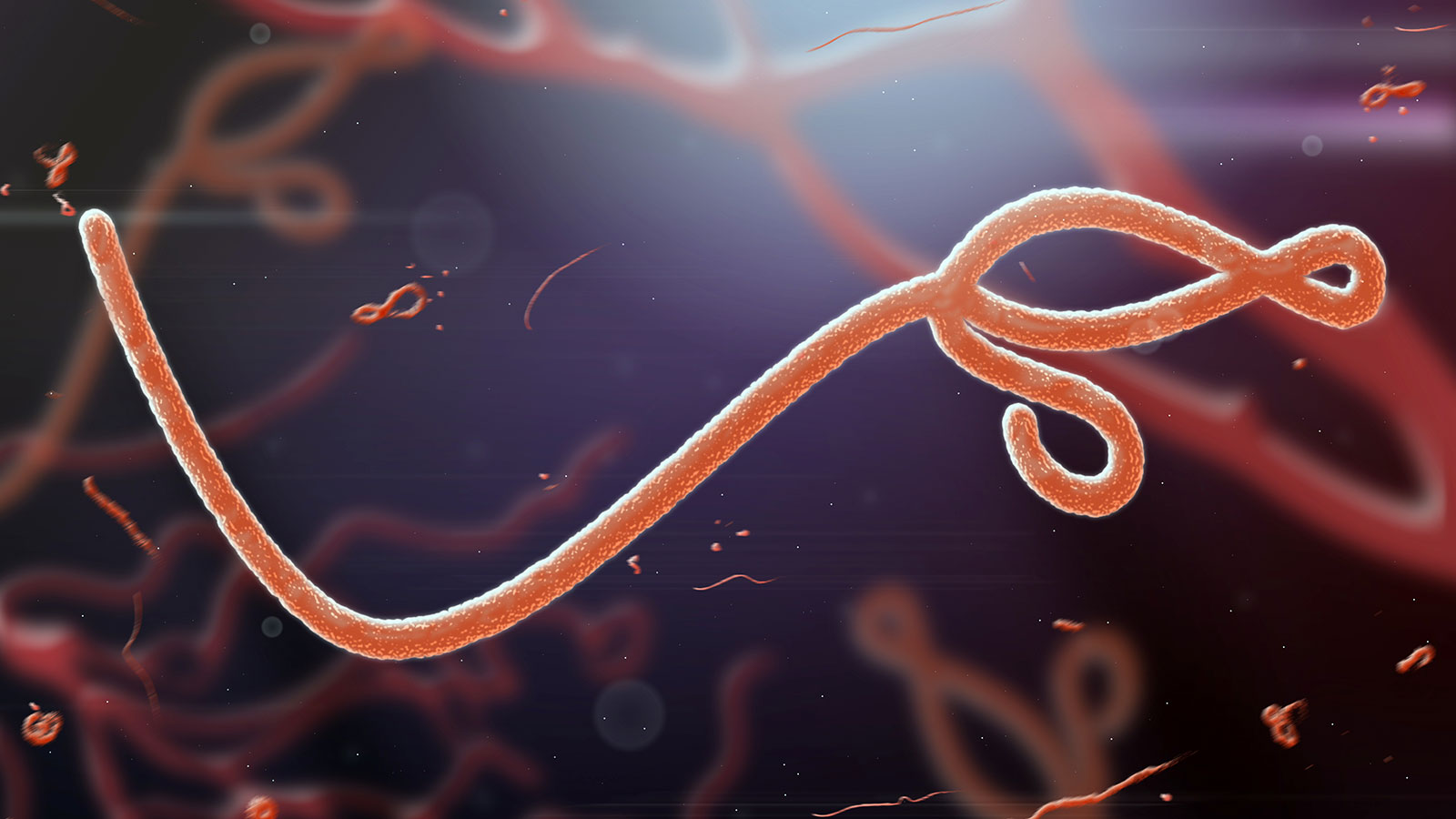

Perhaps you have heard about Ebola, otherwise known as The Most Terrifying Disease Of Our Modern Times (Sorry, MERs; panic is a fickle friend). But you might not have heard that Ebola’s origin story also features a favorite environmental arch-villain? And by “favorite,” I mean “actually the worst”: deforestation.

You see, the most recent outbreak of this particular strain of the Ebola virus began last December, in a town called Meliandou in the sleepy “Forest Region” of Guinea. That is, it used to be forested, as a recent article in Vanity Fair pointed out:

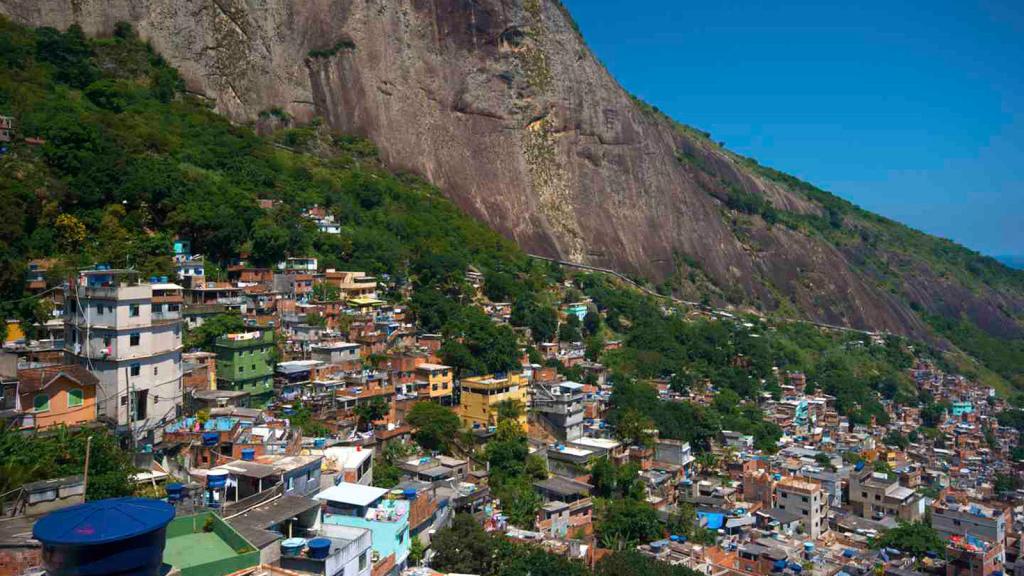

Trees were felled to make way for farms or burned down for charcoal. Endless truckloads of timber were shipped to construction companies. The forest suffered another trauma as mining interests — the Anglo-Australian Rio Tinto, the omnipresent Chinese — pushed aggressively to exploit the country’s natural resources (bauxite mostly). As the forests disappeared, so too did the buffer separating humans from animals — and from the pathogens that animals harbor.

And that buffer was not in place when one fateful fruit bat came into contact with a human toddler late last year:

Ordinary life in Meliandou came to an end on the day last December when the Ebola virus, which had last claimed a fatality thousands of miles away, arrived in the village, most likely in the body of a fruit bat — its natural non-human reservoir, according to a virtual consensus among scientists. Mining and clear-cutting had driven bats from their natural habitats and occasionally closer to people, like those of Meliandou. And fruit bats love palm and mango, which ripen in the village’s remaining trees. Bats also feed in colonies, which makes them tempting targets: a single shotgun blast can bring down 10.

While in many ways Ebola qualifies as a natural disaster, it’s worth remembering that the distinction between “natural” and “human-made” is a fine one. Sandy was a “natural” disaster, for example, but New York City’s bad coastal infrastructure made it worse. Same with Ebola: What could have been an exclusively harmless fruit-bat affair instead took a leap across the thinning fringe of wilderness, traveled by land and by air in our increasingly interconnected world and — well, here we are.

There’s a lot more deep and very sad thinking about epidemics, mourning, and the risks health-workers take to care for others in the Vanity Fair article here. Read it — but maybe bring a box of tissues and a hazmat suit.