👋 Hey there, everyone. I loved hearing from y’all last week about the walkability scores of your neighborhoods — ranging from zero (!) to 97 (!). And, as many of you noted, these numbers don’t always tell the full story. A place with a low score for walking to amenities might still be a lovely place to walk for pleasure or for exercise. And a place with a high score might yet present limitations.

Numbers are instructive in many ways, though. Our key takeaway in last week’s newsletter on walkability was about how data can be a useful tool in advocating for better systems. And this week, we’ve got some new data to share with you all about our understanding of a historic event: Hurricane Katrina. Plus, two data-driven maps designed to help people track their exposure to harmful substances.

Learning more from Hurricane Katrina, 20 years later

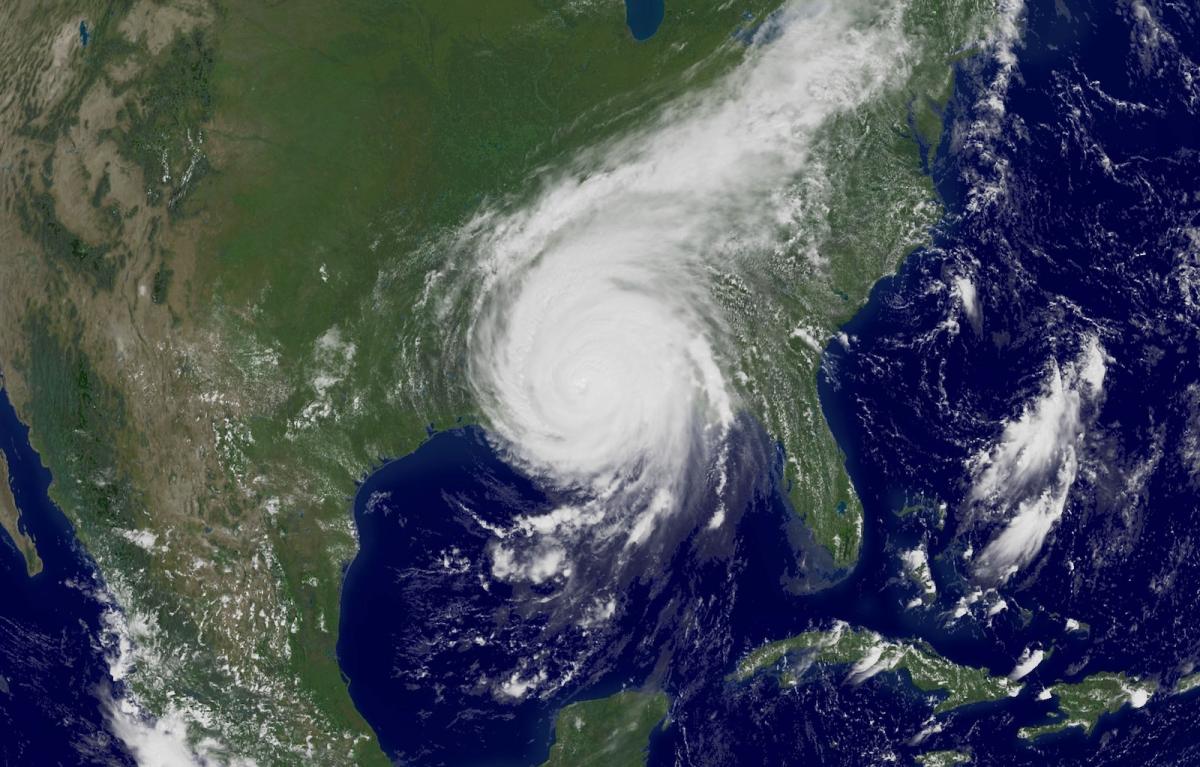

On August 29, 2005 — exactly 20 years ago — Hurricane Katrina made landfall in New Orleans. The devastating storm claimed nearly 1,400 lives and caused some $200 billion in damages (in today’s figures), making it the costliest storm in U.S. history.

Katrina was among the first high-profile, major disasters of the information age. For many, it was a wake-up call to realities that we are now confronting over and over: how flawed human systems breed vulnerability to the increasingly violent forces of nature.

As my colleague Jake Bittle wrote this week, a combination of rising sea levels and sinking ground make the city of New Orleans uniquely vulnerable to flooding. An ever-evolving system of levees and pumps has supported the bowl-like city for centuries — and that system failed when Katrina hit. The American Society of Civil Engineers called it the “the worst engineering catastrophe in U.S. history.”

The disaster was also a crisis of inequality. Predominantly Black and low-income neighborhoods like the Lower Ninth Ward suffered the brunt of the flooding, due to a history of segregation and redlining that forced these residents into more vulnerable, low-lying areas. And despite a mandatory evacuation order for the city, at least 100,000 New Orleanians were not able to leave.

The magnitude of suffering caused by this failing infrastructure, underlying inequalities, and a slow and mismanaged aid response galvanized a new generation of climate and justice leaders, and has informed disaster planning in the decades since.

But calling the storm a climate change-driven event was always a bit murky. Until now.

Two decades after Katrina, the field of attribution science — how researchers measure the contributions of human-caused climate change to extreme weather — has advanced considerably. As my colleague Matt Simon explored this week, a new analysis by the nonprofit Climate Central applied these improved techniques and data to the historical storm, and found that the warm ocean waters over which Hurricane Katrina brewed were made 18 times more likely by climate change. That warming also increased Katrina’s maximum wind speeds by 5 mph.

Katrina wasn’t caused by climate change, but it was fueled by it. That insight not only increases our understanding of the perils of global warming, but also how to prepare for what comes next.

“If Hurricane Katrina were to happen today, it would probably be even stronger and have maybe even more rain and storm surge associated with it, because the Earth has warmed over the last 20 years,” atmospheric scientist Kevin Reed told Matt.

Whether it would also be more destructive depends in large part on the human systems that have been put in place since. The $14 billion improved levee system that Congress invested in after Katrina has protected New Orleans from subsequent hurricanes, including Ida in 2021. Still, in the face of ever rising seas, fast-sinking land, and chart-defying storms, even if the levees get regular maintenance and improvements — something that’s in jeopardy with federal and local cuts — this state-of-the-art system could still be overwhelmed by a direct hit.

Twenty years after it first showed us what climate change would bring, the legacy of Katrina is not only about what we’re doing to the planet, but the consequences of not preparing — not addressing the underlying problems — until it’s too late.

Read more:

- We now know just how much climate change supercharged Hurricane Katrina

- 20 years after Katrina, New Orleans’ levees are sinking and short on money

Share your thoughts

Growing up in the Southeast, I dealt with my fair share of (non-catastrophic) hurricanes and thunderstorms, even a couple of microbursts. Now that I live in the Pacific Northwest, fires and creeping heat waves are bigger concerns. What are the biggest climate-driven threats where you live? And how do you think about preparing for them, on an individual or community level? Reply to this email to share.

More from Grist

📍Lead astray

The city of Chicago has the most lead pipes in the country — and its plan to replace them all will take decades. In partnership with WBEZ and Inside Climate News, Grist mapped all the lead service lines in the city using data from a public records request to explore where the problem is most concentrated. Read more here, here, and here

🐊 Later, alligator

The Miccosukee Tribe in South Florida won a temporary victory when a judge ordered the closure and dismantling of “Alligator Alcatraz,” an immigration detention center set up by ICE in the Everglades. The tribe and environmental groups argued that the government failed to conduct an environmental review and consult the tribe before constructing the facility. Read more

⚖️ See you in court

A group of young people in Wisconsin have joined a growing movement of climate action in the courts. After a historic storm hit the state earlier this month, more than a dozen youth are suing their state’s utility regulator in an effort to force it to consider climate change when evaluating new fossil fuel projects. Read more

In other news

- A new “Methane Risk Map” helps residents visualize the potential health threats from super-emitters near them (Heatmap)

- The Colorado River Indian Tribes are seeking to establish legal personhood rights for the Colorado River on tribal lands (KUNC)

- Meet the lawyer working to hold a Chinese mining company responsible for catastrophic pollution it caused in Zambia (Inside Climate News)

- This international citizen science project enlists photo-taking tourists to help track changes to coastlines (Euronews)

- Next month, more than 150 community events will recognize Sun Day: A celebration of clean energy (Canary Media)

And finally, looking forward to …

… a disaster preparation strategy that takes pets into consideration. I was really moved by this NPR story — another retrospective on the Katrina anniversary that examined a separate crisis created in the city when people had to leave their animals behind, thinking they’d be able to return in just a few days. In some other cases, people weren’t willing to board rescue vehicles without their pets, risking their lives instead. As the story noted, including animal companions in disaster planning is an important aspect of helping to protect people, too.

🐾🐾🐾

“It’s OK, girl,” you murmur to Kiki, stroking her head.

The shaggy, 50-pound mutt is perched in your lap — an arrangement that neither of you prefers. But you’re not complaining. You’re grateful.

Grateful to the neighbor who pounded on your door minutes before the last shuttle bus left for the evacuation point. Grateful for the go-bag you had packed, with Kiki’s meds and yours, now stowed beneath your seat. Grateful to the bus driver, who smiled when she saw Kiki’s silly grin and made you both feel a little less afraid. Grateful your community was prepared for something like this.

— a drabble by Claire Elise Thompson

🐾🐾🐾

A drabble is a 100-word piece of fiction — in this case, offering a tiny glimpse of what a clean, green, just future might look like. Want to try writing your own (and see it featured in a future newsletter)? We would love to hear from you! Please send us your visions for our climate future, in drabble form, at lookingforward@grist.org

👋 See you next week!