It’s official: Climate change is making the world’s water its bitch. We’ve got droughts, floods, funky precipitation, melting glaciers — it’s H2O anarchy out there! And now, as if things weren’t bad enough, we’ve got shrinkage.

In a study published this week in the Journal of Geophysical Research: Biogeosciences, researchers from the University of Texas at El Paso report that Arctic ponds are becoming smaller and fewer, thanks, at least in part, to rising temperatures (unlike the more familiar form of shrinkage that results from decreasing temperatures).

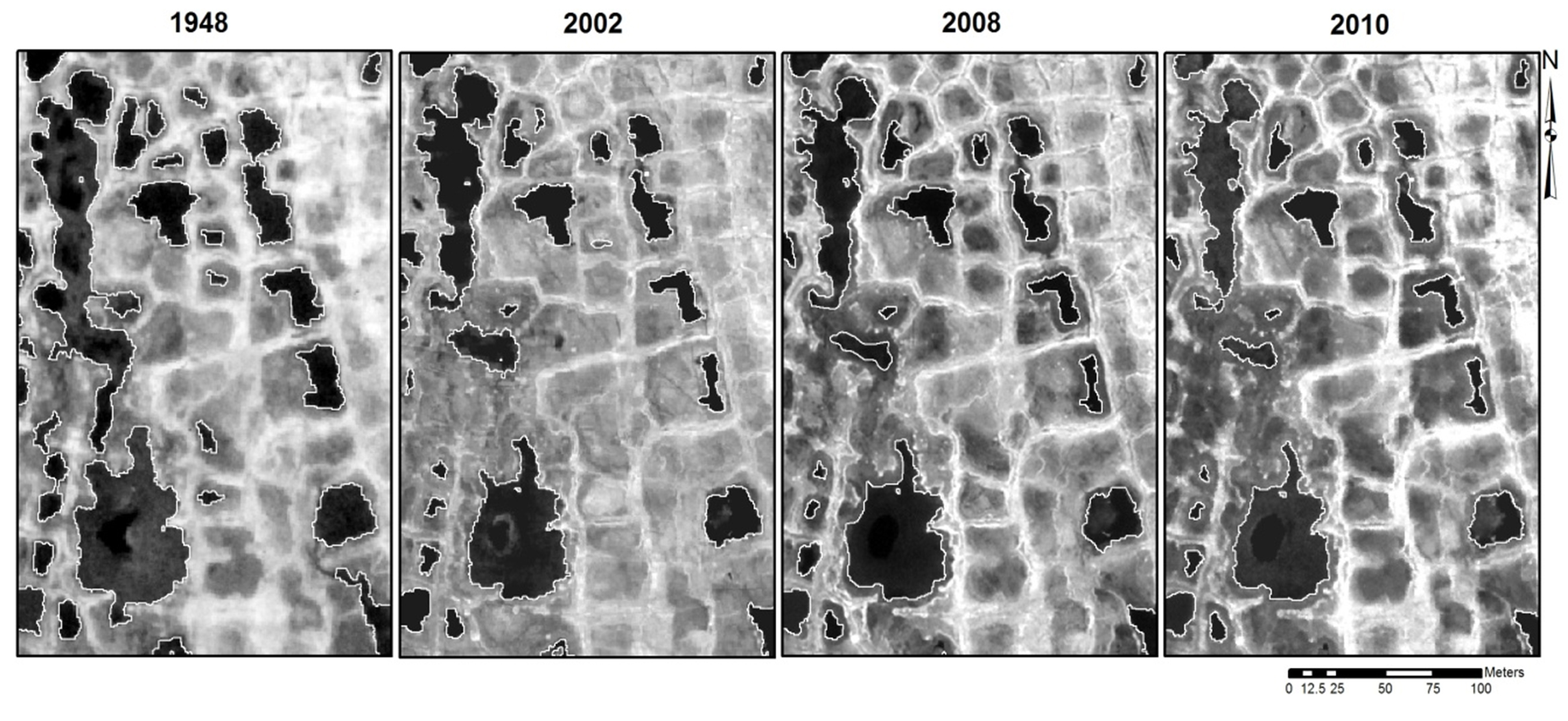

The researchers focused specifically on the upper Barrow Peninsula in Alaska, where temperatures during the long winters average about 10 degrees Fahrenheit and during the short summers about 40 degrees F. Comparing old black-and-white aerial photos from the military to newer satellite images and photos taken from a kite-bound camera, they found that, between 1948 and 2013, the ponds in this region shrank about 30 percent in area and about 17 percent in number.

Arctic pond shrinkage between 1948 and 2010Christian Andresen / UTEP

During that same time period, the average summer temperature in the Barrow Peninsula increased by about 3.6 degrees F. That rise, according to the researchers, could be causing more evaporation from the ponds. It could also be causing more thawing of the frozen, nutrient-rich soil known as permafrost, which, in turn, would cause more plants to encroach on the newly warm and nutrient-rich waters.

“Before you know it, boom, the pond is gone,” the study’s lead author, Christian Andresen, said in a press release.

The images below show how plants took over a pond between 1976 and 2012.

A scientists sampling one of the Arctic ponds in 1976. Christian Andresen / UTEP

Christian Andresen at the same spot, now covered in plants, in 2012. Christian Andresen / UTEP

Andresen also pointed out that this shrinkage could cause problems in the long run:

The role of ponds in the Arctic is extremely important. History tells us that ponds tend to enlarge over hundreds of years and eventually become lakes; ponds shape much of this landscape in the long run, and with no ponds there will be no lakes for this region.

Fewer and smaller ponds could also have impacts on local wildlife and the rate of carbon exchange between the land and atmosphere, Andresen and his colleague say.

So there you have it. Shrinkage. I have to admit, I feel relieved. I was worried that this was going to be awkward, but now that it’s out there, I think we can all agree that it’s just part of life and move on. And of course, by move on, I mean wait anxiously for the next bit of frightening news about what climate change is doing to our planet.