President Barack Obama wanted to do something big to combat climate change. He just couldn’t.

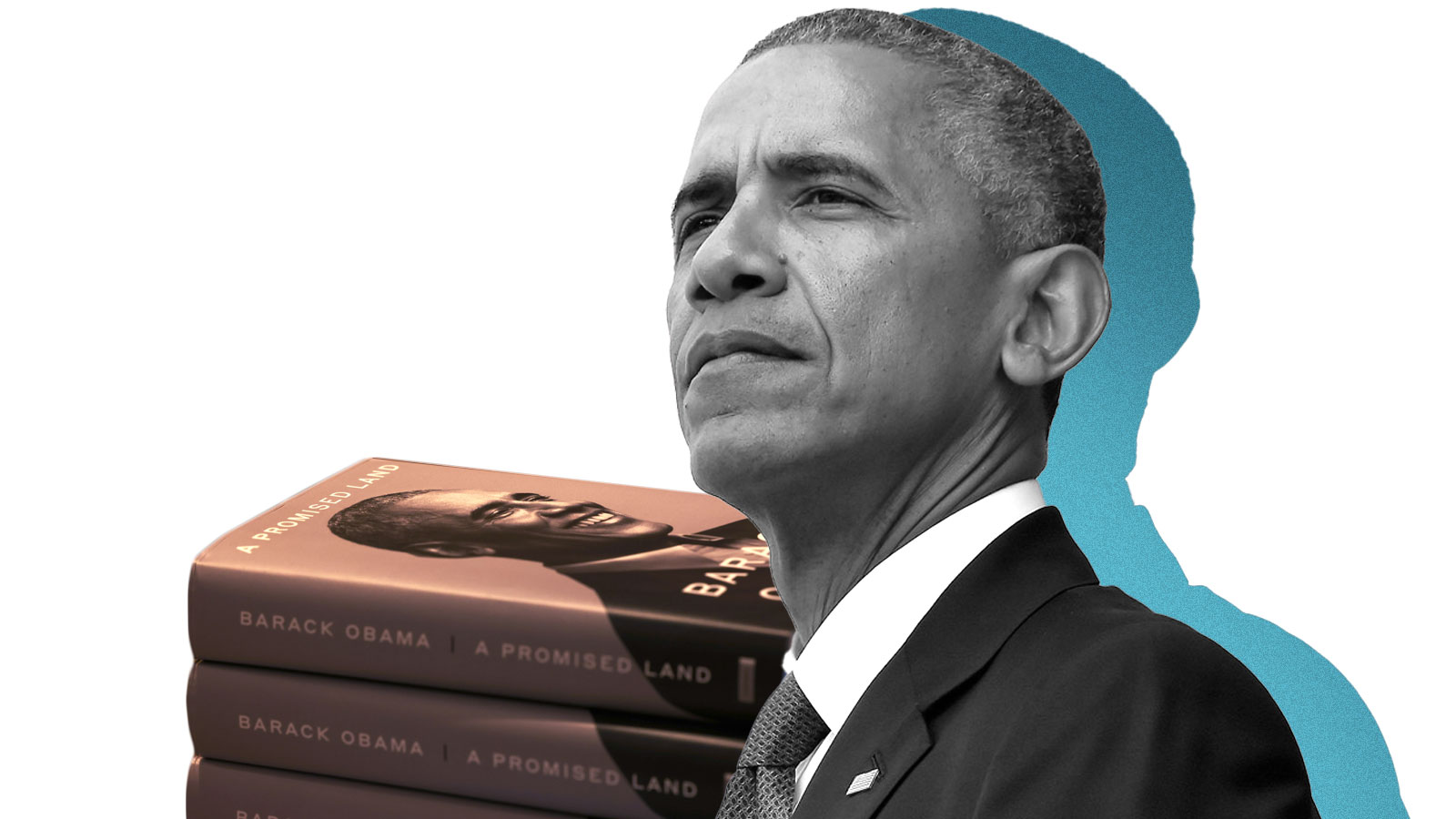

That, at least, is one of the takeaways of A Promised Land, the first installment of the former president’s two-part memoir. According to the 768-page tome — which covers his early political career and first term as president — Obama came into office hoping to address the overheating planet (and “save the tigers” for his four-year-old daughter, Malia). One of his campaign promises was a “cap-and-trade” bill that would have set a limit on the country’s greenhouse gases, aiming to cut U.S. emissions 80 percent by 2050.

Despite the best efforts of Obama and his team of advisors, that ambitious bill never made it through the Senate — setting the United States and the world on track for immense warming in the decades to come. The problem? A massive oil spill in the Gulf of Mexico and obstruction from Senate Republicans.

And now, with President-elect Joe Biden poised to enter the White House, Obama’s struggles serve as a reminder of the limits of presidential power — especially with an issue as global and far-reaching as climate change.

To be sure, Obama’s chances to pass climate legislation were never that good. Even though his proposed bill was similar to policies advanced by his rival for the presidency, John McCain, and in the 1990s by former president George H.W. Bush, global warming hadn’t yet played a big role in national politics. During the 2008 election, Obama writes, “the average Democratic voter ranked climate change near the bottom of their list of concerns.” (In a sign of how much the times have changed, a recent NPR poll found that 22 percent of Democrats today – and 12 percent of all likely voters — now consider climate change the “most important issue” facing the country.)

To make matters worse, Democrats never had a filibuster-proof majority when they held the Senate, meaning that bills effectively needed 60 votes to pass. Even after a version of cap-and-trade passed in the House, Obama and his aides would need to peel off several Senate Republicans in order to turn the landmark bill into law.

In A Promised Land, Obama says that he and his aides first believed that they would get those votes through McCain, a known supporter of cap-and-trade. “In the (very) brief halo of good feeling right after the election, he and I discussed working together to get a climate bill passed,” Obama writes. But in the new, post-election GOP, Republicans weren’t rewarded for bipartisanship. McCain, facing a reelection challenge from a right-wing radio host, soon dropped off the bill entirely.

The next hope was none other than Senator Lindsey Graham, the Republican from South Carolina. Graham was a much more slippery negotiating partner: According to Obama, Graham “liked to play the role of the sophisticated, self-aware conservative” — but when it came to taking a stand, the senator always “seemed to find a reason to wriggle out of it.” Graham finally agreed to help to deliver the votes in exchange for opening coastlines for oil drilling. The deal seemed doable.

Then came the Deepwater Horizon oil spill in April 2010, and, in Obama’s telling, the entire plan came crashing down. As millions of barrels of oil surged into the Gulf of Mexico, the former president realized that environmental groups would now reject any deal that involved more offshore drilling — giving Graham the perfect excuse to back out. “My already slim chances of passing climate legislation before the midterm elections,” Obama writes, “had just gone up in smoke.”

The world knows what happened next. Democrats lost, badly, in the 2010 midterm elections, and Obama’s party hasn’t controlled both houses of Congress since. His administration did manage to accomplish several things on climate, anyway: It set stricter fuel efficiency standards on cars and trucks, wedged $90 billion worth of clean energy spending into the 2009 Recovery Act, and pulled international climate negotiations back from the brink of disaster. But just six years later the Trump administration tried to unravel many of those actions – taking the U.S. out of the Paris Agreement and dismantling Obama-era environmental protections.

It’s a grim sign for Democrats as President-elect Joe Biden prepares to take office in January. At the moment, Democrats hold only 48 seats in the Senate — 10 fewer than Obama had to work with in the first two years of his term — and only a narrow majority in the House. Biden will be able to unravel many of Trump’s worst environmental rollbacks, and set some new rules of his own. But when it comes to comprehensive climate bills, he will be likely be stymied by the same problems as his Democratic predecessor in the White House.

At the end of A Promised Land’s chapter on climate change, Obama returns to the White House after a whirlwind trip to the Copenhagen Climate Change Conference in 2009 where he battled with the Chinese delegation over who should take responsibility for cutting emissions. “All that,” he writes of his trip, for a temporary agreement that was effectively a “pail of water thrown on a raging fire.”

His final thought — like most of the book — serves as both a warning and a plea for patience: “I realize that for all the power inherent in the seat I now occupied, there would always be a chasm between what I knew should be done to achieve a better world and what in a day, week, or year I found myself actually able to accomplish.”