The United States is about to embark on an experiment inspired by one of the New Deal’s most popular programs. On Wednesday, the Biden administration authorized the creation of the American Climate Corps through an executive order. The program would hire 20,000 young people in its first year, putting them to work installing wind and solar projects, making homes more energy-efficient, and restoring ecosystems like coastal wetlands to protect towns from flooding.

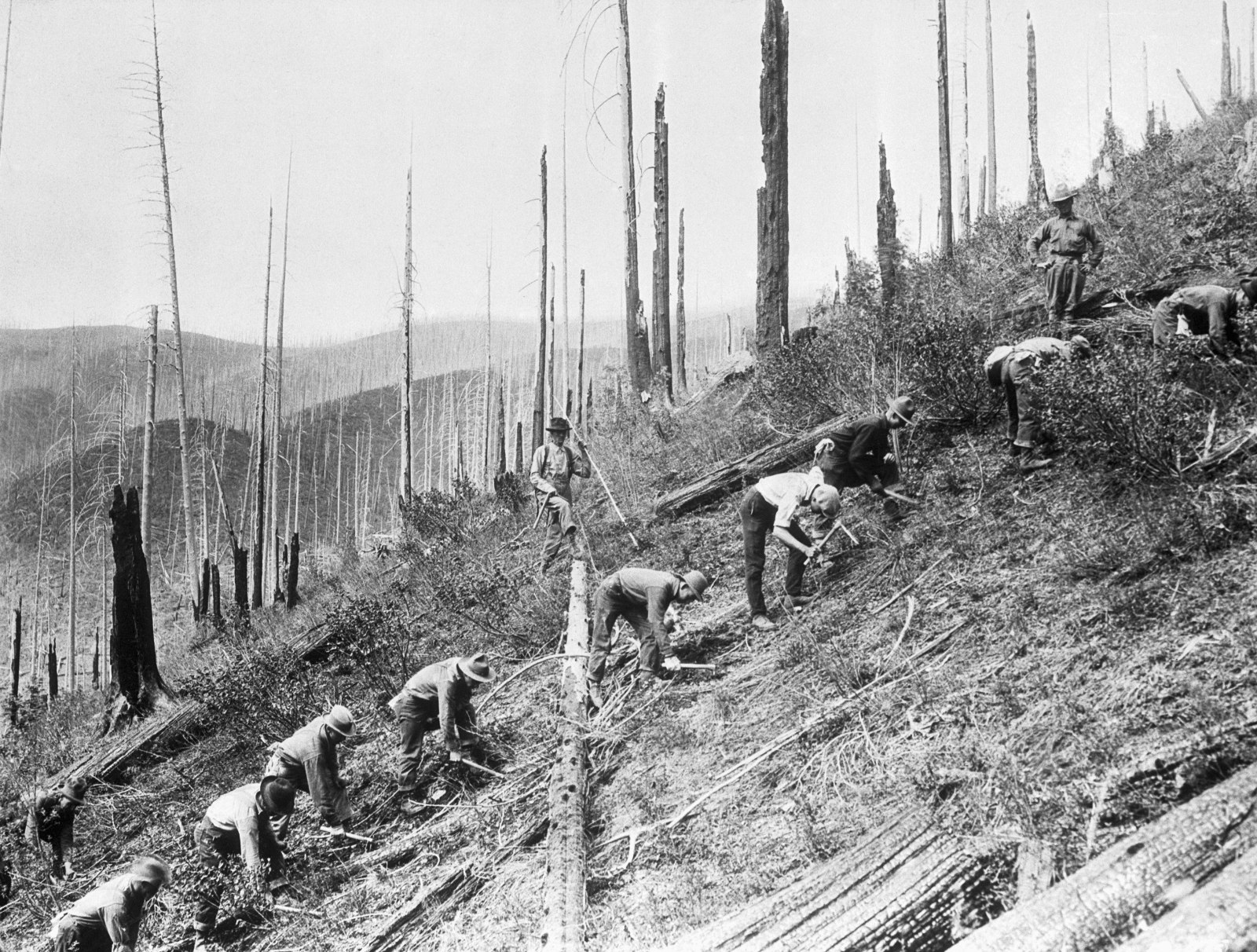

The idea has been in the works for years. It was first announced in President Joe Biden’s early days in the White House in January 2021, tucked into a single paragraph in an executive order on tackling the climate crisis. At the time, it was called the Civilian Climate Corps — a reference to President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s Civilian Conservation Corps, launched in 1933 to help the country survive the Great Depression, which was responsible for building hundreds of parks, including Great Smoky Mountains National Park, as well as many hiking trails and lodges you can find across the country today. Early versions of Biden’s trademark climate law that passed last year, the Inflation Reduction Act, included money for reviving the CCC. But that funding got cut during negotiations last summer with Senator Joe Manchin, a Democrat from West Virginia, and the program was assumed dead.

Now it’s back, with a name change. Biden’s executive order promises that the American Climate Corps “will ensure more young people have access to the skills-based training necessary for good-paying careers” in clean energy and climate resilience efforts. There are plans to link it with AmeriCorps, the national service program, and leverage several smaller climate corps initiatives that states have launched in California, Colorado, Maine, Michigan, and Washington. However, the order didn’t provide details on what kind of funding the program is getting or how much workers will get paid. The White House also launched a new website where you can sign up to get updates about joining the program.

Reviving the Civilian Conservation Corps is widely popular, with 84 percent of Americans supporting the idea in polling conducted by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication last year. Mark Paul, a professor of public policy at Rutgers University, said the new name that swapped “Civilian” for “American” leans into patriotism in an effort to broaden the program’s appeal even further.

“I think that right now we are in a fight for the very soul of the nation,” Paul said. “President Biden and other Democrats are trying to brand climate [action] as not only good for the environment, but good for America. And I think that’s precisely what they are trying to convey with this name change, that climate jobs are good for the American people.”

The program could also be an attempt to appeal to young voters ahead of the 2024 presidential election. The administration drew criticism from climate activists when it approved the Willow oil project in northern Alaska in March after concluding that the courts wouldn’t allow them to block it. After that decision, polling from Data for Progress found that Biden’s approval ratings on climate change dropped 13 percent among voters between the ages of 18 to 29. The revival of the CCC has long been an item on progressives’ wish lists — back in 2020, Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, a Democrat from New York, reportedly sold Secretary of State John Kerry on making the program part of Biden’s platform during the 2020 presidential campaign.

“I am thrilled to say that the White House has been responsive to our generation’s demand for a climate corps and that President Biden acknowledges that this is just the beginning of building the climate workforce of the future,” Varshini Prakash, the director of the youth-led Sunrise Movement, told reporters ahead of Biden’s announcement.

To be sure, the American Climate Corps could run into problems. If it’s modeled off AmeriCorps, the jobs might not exactly qualify as “good jobs” — AmeriCorps members are more like volunteers who get a small stipend, often living close to the poverty line. The White House, for its part, is selling the program as a path to good careers. The administration “will specifically be focused on making sure that folks that are coming through this program have a pathway into good-paying union jobs,” said White House National Climate Adviser Ali Zaidi on a call with reporters on Tuesday about the announcement. “We’re very keenly focused on that.”

The initiative could help bolster the ranks of workers like electricians, according to Zaidi, addressing the country’s shortage of skilled workers who can install low-carbon technologies like electric vehicle chargers and heat pumps. “We’re hopeful that the launch of the American Climate Corps will help accelerate training for a new generation of installers, contractors, and other tradespeople who are, at the end of the day, the ones who make these great ideas a reality,” Paul Lambert, co-founder and CEO of Quilt, a heat pump company in California, said in a statement to Grist.

With the goal of hiring 20,000 a year, the new program is much smaller than many activists had hoped: The original CCC employed 300,000 men in just its first three months (women were excluded until Eleanor Roosevelt’s “She-She-She” camps opened in 1934). Some progressives, like Ocasio-Cortez, were hoping a climate corps could employ 1.5 million people over five years. Assuming all goes well, the program could expand. Paul speculates that the Biden administration is starting small as “proof of concept to the American people to show that this program can work and that it is worthy of investment.”

If interest in the American Climate Corps is high, those 20,000 slots could fill up quickly. Among the 1,200 likely voters polled by Data for Progress two years ago, half of those under 45 said they’d consider joining, given the chance.

“I teach youth day in and day out, and one of the biggest problems we face right now is youth feeling like they don’t know what to do,” Paul said. “And now we have a program that the U.S. government is facilitating to point to and say, ‘You know, if you want to help, here’s one way that you can contribute to decarbonizing our nation.’”