This summer, the Twofer-Pillikin forest health project, south of Lake Tahoe, was finally ready to go. Over the course of years, Forest Service scientists had fanned out to study some 10,000 acres of ponderosa and sugar pines. Hydrologists had charted the courses of ephemeral streams. Botanists had surveyed for rare plants, like the Pleasant Valley mariposa lily and yellow bur navarretia. And biologists had tweaked the plans to avoid disturbing Sierra Nevada yellow-legged frog habitat, and to create meadows for the Western bumblebee.

Jerry Keir, executive director of the nonprofit Great Basin Institute who was helping to manage the project, had lined up eight contractors to bid on the work. The crews would be responsible for thinning dense sections of forest and removing enough brush to allow for prescribed burns and wildfires to safely move through the trees — measures that should keep flames small and allow firefighters to stop their spread. Lastly, Keir had cobbled together the money to pay for it all, signing a final agreement for a $1.2 million grant from the state of California’s Sierra Nevada Conservancy in August.

A week later, the Caldor Fire erupted and, as Keir put it, “a whole lot of time and money went up in smoke.”

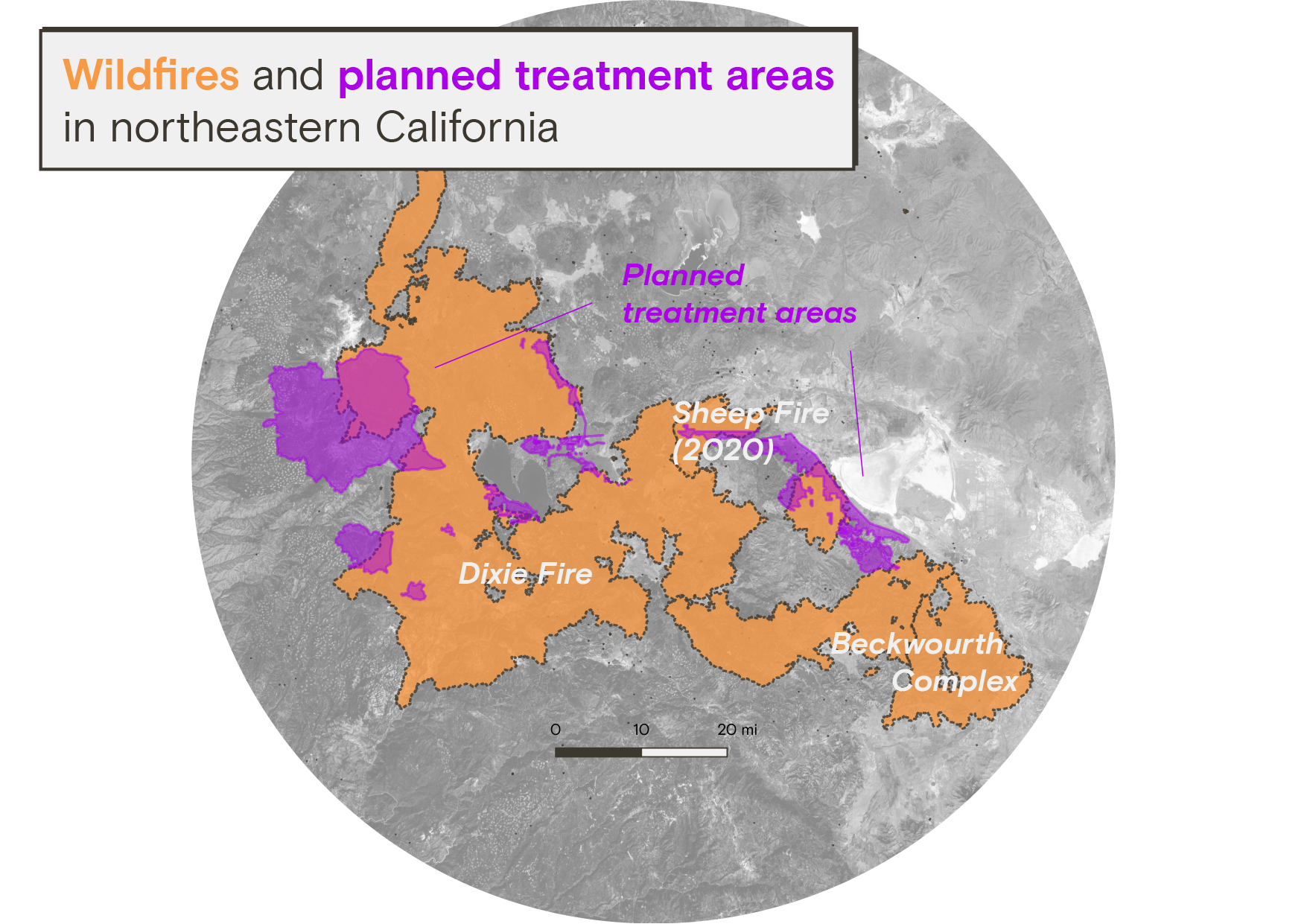

Some 150 miles to the north, Tom Esgate, operations manager for the Lassen

Fire Safe Council, was also watching in dismay as fire swept through one planned project area after another. “If you want to see a wildfire come to your community, all you need to do is have Tom Esgate plan your project,” he said wryly. “It’s been like whack-a-mole around here.”

Twenty miles to the west, the Dixie Fire was burning up the plans of the South Lassen Watershed Group, a landscape management collaborative — making irrelevant tens of millions of dollars worth of project planning and prep work, said Jonathan Kusel, executive director of the nonprofit Sierra Institute.

“It is at best demoralizing to see these projects thwarted by precisely the thing they were meant to prevent,” Kusel said.

California has dramatically ramped up its spending on wildfire resilience over the last few years, planning forest thinning and prescribed burns in the places most at risk of burning. Officials have credited recently completed projects with saving thousands of homes. But even though the state is moving quickly, fires are moving even faster.

Blazes this year have burned portions of at least 11 forest protection projects funded by the state of California before they even had a chance to get started. That number may be as high as 20 when all of this season’s fires have been accounted for, said Angela Avery, executive officer of the Sierra Nevada Conservancy, a state agency leading efforts to protect natural ecosystems.

Not included in that estimate are the many planned projects on private and federal land. The Eldorado National Forest had planned to perform forest health work — tree thinning, brush clearing, and prescribed burns — on 45,000 acres that the Caldor Fire covered this summer. And the Forest Service has not yet tallied up the number of planned hazardous fuels reduction projects burned by the 200,000-acre Monument Fire and 120,000-acre McFarland Fire in the Shasta-Trinity National Forest, or the 190,000-acre River Complex in the Klamath National Forest — the list goes on and on.

There are examples from around the U.S. West of fire prevention projects, delayed by years of legal wrangling, burning before any action on the ground could remediate the hazard. But the situation in California is unprecedented. Climate change is squeezing the water out of California forests — melting snow earlier, drying up seasonal streams, and leaving the trees competing for receding aquifers. “All of the fuels experts I have been around — people with 40-, 50-year careers — have never seen conditions like this,” said Jeff Marsolais, supervisor of the Eldorado National Forest. “We were ordering up air tankers for initial fire attacks in January. It was like this slow-motion catastrophe coming at us. It just got drier and drier, and we set record after record.”

Not far from the Twofer-Pillikin project area, the road leading into the Caldor Fire’s burn scar near Jenkinson Lake was closed one early September morning, guarded by a pair of soldiers in tan military Humvees. They were waiting for California Insurance Commissioner Ricardo Lara, there to see some of the fire protection projects tested by wildfire, and waved through the handful of cars accompanying him, including mine.

In a few miles, the convoy passed one partially completed forest management project, with a pile of wood the size of a house waiting to be burned. Next, it drove by a thinning project that had burned before it could begin, followed by a completed fuel break. The fact that this one fire had hit so many projects in various stages of completion is testament to how much effort California is directing toward fire safety — and also to the sheer size of the Caldor Fire. After the King Fire burned near here in 2014, various government agencies and public interest groups in the area began collaborating on massive fire adaptation plans along Highway 50 between Sacramento and South Lake Tahoe.

Tom Tinsley, a forester for the California Department of Forestry and Fire Protection — commonly known as Cal Fire — stepped out of his truck and pointed into a clearing at the top of a drainage near Jenkinson Lake. Workers had thinned this patch of land to create an area where fire would be starved of fuels, he explained. And in this spot, beneath wide-spaced ponderosa and sugar pines, it was clear that the fire had weakened: The trees were a healthy green, and patches of unburnt grass stood among them. Without this fuelbreak, Tinsley said, it might not have been safe for firefighters to make a stand here and stop the fire in the dense portions of forest they’d just driven past. “If things really went sideways there was a place just up the road where they could take refuge… and survive.”

Crouching over a map, Lara motioned to the neighborhoods on the edge of the fire and asked, “So how many people would you say live here?”

“We looked at that,” mused Mark Egbert, a local National Resource Conservation District officer who has spearheaded several fire adaptation projects in the area. “There are maybe 8,000 structures. And not only were they able to stop the fire here and save houses, they were able to protect active spotted owl and eagle nests.”

The work isn’t cheap, Egbert acknowledged. It cost some $1,400 per acre. “But compare that to fire suppression costs,” he shrugged.

“Or losing your insurance,” Lara added. “Or losing your home.”

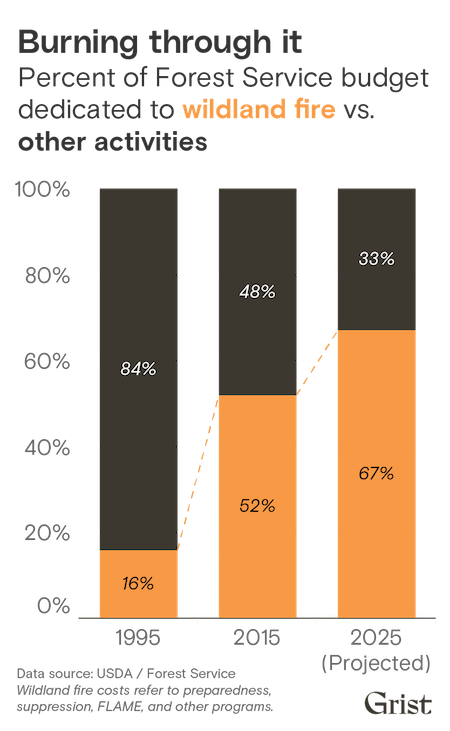

Money has long been a limiting factor: As wildfires get bigger, the cost of fire suppression has eaten up the Forest Service’s budget, leaving less money for anything else. But that may be changing. California has increased its funding for forest thinning, controlled burns, and other management more than 16-fold this year, to $1.5 billion. The bipartisan infrastructure bill contains some $2.7 billion for prescribed burns and fuels reduction nationwide, and the tenuous Democratic reconciliation bill puts $14 billion toward these efforts.

But that may be changing. California has increased its funding for forest thinning, controlled burns, and other management more than 16-fold this year, to $1.5 billion. The bipartisan infrastructure bill contains some $2.7 billion for prescribed burns and fuels reduction nationwide, and the tenuous Democratic reconciliation bill puts $14 billion toward these efforts.

“When we can get the Forest Service funded at the level needed to get the work done, we will start seeing huge results,” said Jessica Morse, California’s Deputy Secretary for Forest Resources Management, in a public meeting earlier this month.

But not even huge results will stop the most ferocious fires. The town of Grizzly Flats, which weathered the full force of the Caldor Fire when it first exploded in August, is today an eerie moonscape. The trees are blackened sticks. Houses are mere outlines. Tree roots have burned underground leaving spidery holes in the dirt. A thick frosting of ash shifts easily to reveal the orange mineral earth beneath — the living topsoil has been vaporized.

The people living in Grizzly Flats understood the risk of wildfire — and they were working hard to mitigate that risk, clearing brush and thinning trees around town. But it was too little and too late.

“If all the planets align and the fire comes ripping in, we just need to get out of the way,” Tinsley explained, while showing Lara around Jenkinson Lake. “We can deal with record vegetation dryness, we can deal with 114-degree weather, what we can’t deal with is this,” lifting a forefinger to the hot air rising up the canyon.

Former Cal Fire Chief Ken Pimlott shuddered. “This wind. I’m nervous just standing here.”

Firefighters, foresters, politicians, and environmentalists are all spending an enormous amount of money and time to adapt to this new era of megafires. But, when many of the forest protection efforts are burning before they can even get started — such as the Twofer-Pillikin project and the many others the convoy drove by as it passed through the Caldor Fire’s burn scar earlier this month — it sometimes feels as if all these efforts are simply too slow.

If society decides it wants to move more quickly with these projects, it must readjust the way its institutions consider risk. The Forest Service, for example, is bound by the National Environmental Policy Act, which, as Esgate pointed out, requires meticulous work to ensure projects do no harm. But the risk of inadvertently damaging a rare marten den, may — in this new, climate-changed era — be outweighed by the risk of delay.

Blackened trees and a burned sign mark the path of the 2021 Caldor Fire.

“I saw a spot where the fire had moved through private land, where people had been able to get in and clean it up, and it was okay,” Esgate said. “Then it got to the forest boundary where there was a 20-foot wall of brush and downed timber from the last fire, and it’s like a bomb went off.”

In 2019, flames from a burn pile escaped and charred 3,500 acres, drawing widespread criticism. But the fire had a mostly beneficial effect on the landscape: It consumed woody debris that would have made future blazes hotter. Most trees survived and, with less competition for water, grew back healthier and greener. When the Caldor Fire reached that area, it passed to either side.

To help rebalance the risk of taking action against the risks of inaction, state legislators recently passed a bill to shield controlled burn practitioners from liability, and Lara, the insurance commissioner, pushed to create a $20 million prescribed-fire liability backstop fund.

For Marsolais, the Eldorado Forest Supervisor, the biggest problem is the lack of businesses to do the work on the ground, and make use of the wood coming out of the forests. There’s currently no market for trees salvaged from fires. The timber mills have more logs than they can process coming in from torched private timberland. So workers pile up enormous mounds of brush and logs, then burn them.

“We need to create a restoration economy around forest management, in the same way that the Pacific Northwest did around salmon restoration,” Marsolais said. That would mean leaving behind the boom and bust cycle of western resource extraction, and building up a stable ecosystem of businesses that could offer good jobs and sustainable wood products, while also maintaining forests.

Scientists and nonprofit staffers have already begun going into the recently burned project areas to see if it makes sense to proceed with plans in sections that escaped the flames. In the best case scenarios, the fire will have done the necessary work itself – clearing out thickets and killing the occasional tree. In severely burned areas, groups may have to restart the environmental assessment process, or give up. But even before this fire season ends, the clock to complete the next round of projects has begun ticking down.

“We are running out of time. That’s the bottom line,” said Keir. “And it’s hard to watch.”

Correction: This story previously used an outdated version of the Lassen Fire Safe Council’s name.