This story is part of Grist’s Summer Dreams arts and culture series, a weeklong exploration of how popular fiction can influence our environmental reality.

Like many older millennials, I spent quite a few of my after-school hours in the 1990s parked in front of the TV. You name it — if it came on after 3:15 p.m. and didn’t require cable, I probably watched it. But thinking back on those many hours 30 years later, one show’s staying power rises above the rest: Captain Planet.

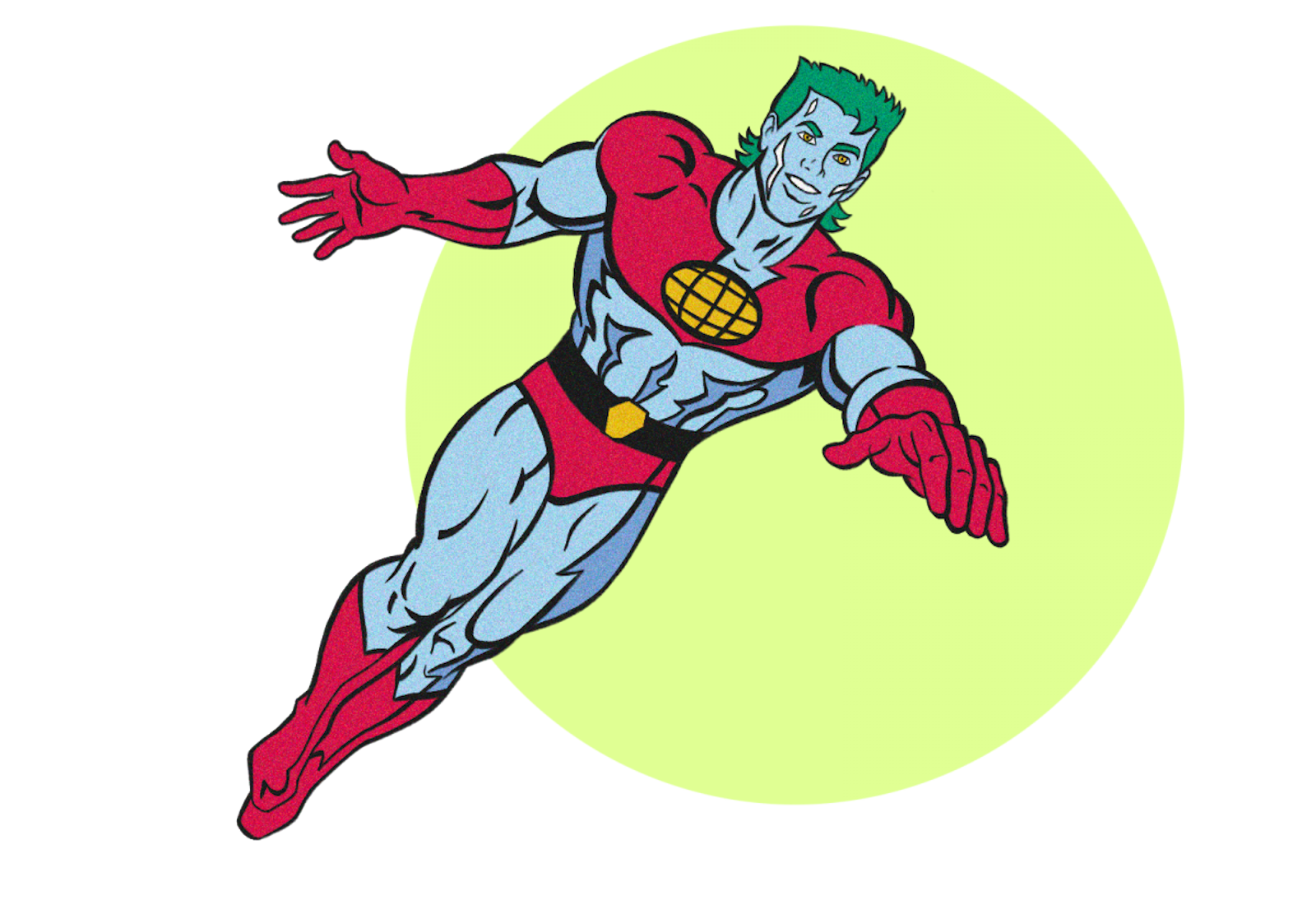

For those unfamiliar with the series, Captain Planet was an unlikely hit. It starred a preachy, green-mulleted, pollution-sensitive superhero who used his powers to combat issues like oil spills, greenhouse gases, and nuclear waste. He could only be summoned by the Planeteers, a group of five internationally diverse teens with magical, element-themed rings: Earth, Fire, Wind, Water, and Heart (the last one being a combination of empathy, telepathy, and extreme persuasion). When those powers combined, as they predictably did at some point every episode, Captain Planet would rise majestically into the air, ready to do battle with a wide array of pollution-spewing supervillains.

Compared to the dark and brooding superheroes of the DC and Marvel universes, Captain Planet was a bit of a dorky doodle. Sure, he could deliver a well-timed dad pun while punching an offshore drill rig, but he also spent a significant portion of his airtime straight-up lecturing viewers about recycling and conserving electricity. All the same, kids like me kept watching. The series was one of the longest-running cartoons of the 1990s, with six seasons, 113 television episodes, and one set of Burger King collectible action figures.

But according to executive producer Barbara Pyle, the show’s success had nothing to do with selling merch. “Our mission was to inspire and to educate the next generation of environmental activists,” Pyle said. She and producer Nicholas Boxer made it a point to slip as much planetary realness into the show’s fantastical plotlines. In fact, Pyle says many ideas were taken directly from the Global 2000 Report to the President, a 1980 paper commissioned by Jimmy Carter that warned of environmental disaster should policies fail to account for the world’s booming population growth.

“People ask me, ‘how on earth did you make all this stuff up?’” Pyle said. “Well, we didn’t make it up. Each episode of the show was based on a real issue in a real culture someplace.”

It was no easy task. Pyle and Boxer had previously worked together on documentaries about global social issues, but translating environmental concepts into a kid’s show was a different kind of challenge. “The show was both revolutionary and flawed,” said Boxer. “It was very hard to take these really complicated subjects and integrate them seamlessly into good storytelling… The best episodes felt thoughtful and cohesive. The worst ones were kind of a mess. ”

Pyle’s interpretation is a bit more forgiving.“We did our homework, and the science was clear,” she said. “We knew there was going to come a time when it would be necessary for an entire generation — your generation — to speak with one voice on behalf of the planet. In some ways, the entire Captain Planet series was about preparing us for this moment.”

Watching Captain Planet in 2021 is a lot less entertaining than it was in 1990.

As an 8-year-old, I focused on the action sequences, the cool time-travel narratives, and the inevitable triumph of good over evil. The environmental hazards and villains I saw on the screen were so cartoonishly over the top, it didn’t occur to me that they might pose actual threats to my future wellbeing. I assumed it was a piece of fiction, like talking gargoyles or sewer-dwelling mutant turtles. Doing my part for the planet seemed as easy as cutting the plastic rings on a six-pack of soda or flipping off the light in an unoccupied room.

But the seeds of the real climate crisis — the one that adult show creators like Pyle and Boxer knew was coming — were always there in the show’s plotlines. Take, for example, the two-part, season one episode “Two Futures,” in which pig-faced villain Hoggish Greedly decides to open up a golf resort in the Arctic. Naturally, he and his sidekick solicit the aid of mad scientist Dr. Blight — voiced by none other than actress Meg Ryan. Greedly’s strategy is to go back to the 1950s and “burn all the coal and fossil fuels” and use global warming to melt all the ice.

The arc is kind of intense (and disturbingly prescient) for a kids’ cartoon show. That’s because Pyle had a secondary audience in mind: parents. “I wanted to make a show that was cross-generational,” she said. “In my head, my target demographic was people born around 1985. But I was hoping parents or grandparents watching alongside kids would pick up on the message too.”

That family edutainment goal affected a lot of the show’s writing. Pyle didn’t want kids to see their family members as evil, ecologically speaking. “That’s one of the reasons we made the bad guys and their plans so ridiculous,” she explained, “We tried to point the finger at behaviors rather than industries. That way, no child would go home and say, ‘Oh, daddy, you’re in a blah blah business.’ It would be horrible for some child to see their family member as a Captain Planet villain.”

Unlike the show’s exaggerated villains, the inspiration for the Planeteers were very much grounded in reality. When creating the characters, Pyle drew inspiration from specific individuals, many of whom were prominent in the environmental movement of the 1980s and 1990s.

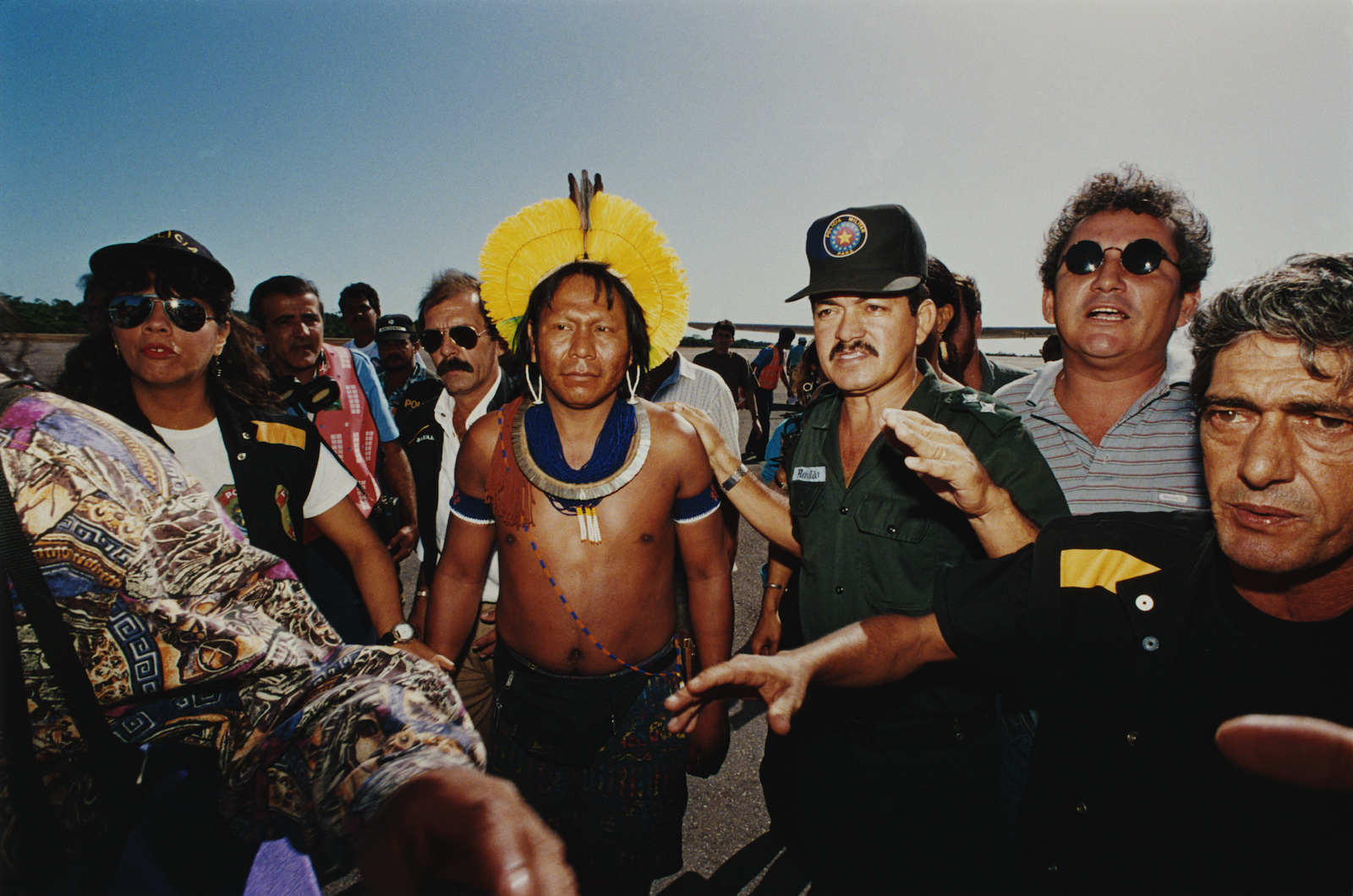

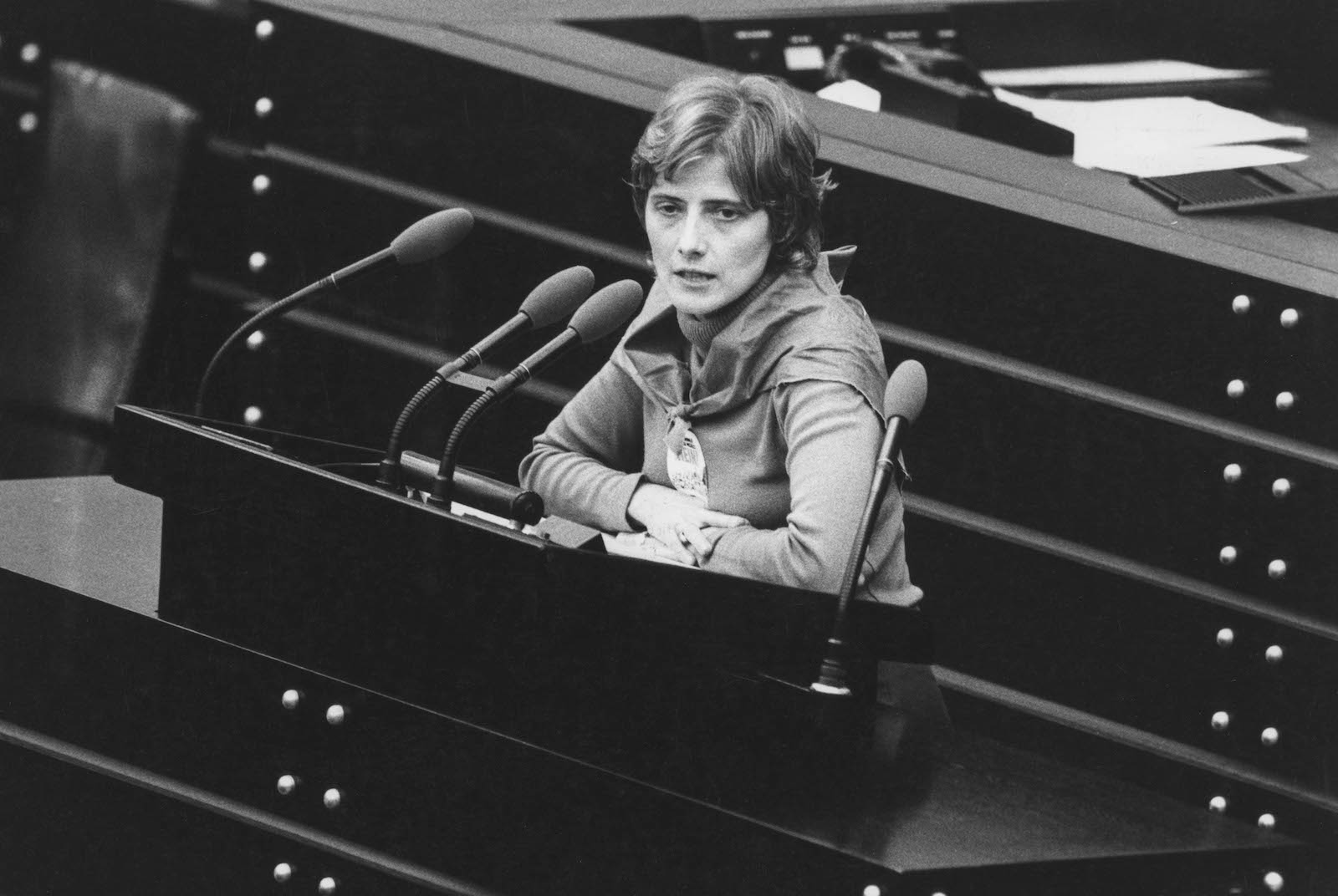

Linka, who controlled wind, was loosely based on German Green Party co-founder Petra Kelly. Gi, the bearer of the water ring, was inspired by Chee Yoke Ling, a Malaysian human rights advocate who attended the 1992 U.N. “Earth Summit” Conference in Rio de Janeiro. Fiery Wheeler was more of an everyman — a mishmash of Pyle’s father and her best friend from New York. Ma-Ti, who possessed the power of heart, was based on Paulinho Paiakan, chief of the Kayapó people and one of the best-known Indigenous defenders of the Amazon rainforest. Kwame, who controlled earth, was a combination of several young men — two from Zimbabwe and one from Ghana — that Pyle had met while making environmental documentaries.

Barbara Pyle based many of the Planeteers on real-life environmental activists active in the 1980s and 1990s. Heart-power Planeteer Ma-Ti was based on real-life activist Paulinho Paiakan, left, a leader of the Kayapo people in Brazil’s Amazon Basin. Wind-power Planeteer Linka was loosely inspired by German Green Party co-founder Petra Kelly, RIGHT, seen here in 1983. Photos by Scott Wallace / Getty Images, Gaby SOMMER / Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images.

As for the unifying character, the name had come from famously eco-conscious media mogul Ted Turner, who hired Pyle in 1980 to make critical global issues more fun and entertaining. “Captain Planet!” he allegedly exclaimed to Pyle. When she asked who that was, he responded, “That’s your problem.”

“On some level, we had lost faith that adults were really paying attention to the problem,” Boxer recalled. “So, we said, let’s go to the kids, in an entertaining way.”

Pyle liked the idea of a kids’ show to get the big takeaways from landmark reports, like the Global 2000 Report to the President, across to a wider audience, but she didn’t think the world needed another beefy superhero. She started working on the project with Boxer, who suggested they make sure Captain Planet would only make an appearance after the Planeteers had identified the problem and come up with their own plan. Instead of a brawny savior, they pushed to make Captain fun-loving, lean, and dependent on others — a metaphor for teamwork.

Some people didn’t get it. Boxer remembers having lunch with a high-ranking TV executive and being told: “I don’t like Captain Planet. I don’t believe in it. And I don’t think any cartoon should have a message.”

Boxer was unphased. “I told him, ‘Everything has a message. The question is whether the message is intended or not. At least we know what we are trying to say.’”

Almost 31 years have gone by since Captain Planet first hit the airwaves and both a lot and too little has changed. We ‘90s kids who watched the show are all grown up now, able to vote and act and weigh our own decisions against their impact on the very real climate crisis still in progress. The power is ours, for real this time.

The weight of that realization is something I now grapple with. Sure, I still recycle and turn off lights, but now I’m keenly aware that individual actions simply aren’t enough to stave off the worst effects of climate change. Rather than viewing that purely as motivation to do more, I’ve become disillusioned, compromising, anxious. In other words, I grew up.

And I’m hardly alone: Back in 1990, TIME magazine dubbed my generation the “ecokids,” calling us, “the best hope for the cause of preservation.” The article quoted several earnest youngsters who vowed to keep fighting for the planet come what may. In 2019, TIME staff writer Olivia B. Waxman tracked down many of the same sources to ask how they felt about that pledge as adults. While some had carved out careers in the environmental movement and felt the cause had made progress, others had become jaded and given up hope.

Pyle, on the other hand, has become even more unrelenting in her optimism. Over the years, she learned of groups of real-life planeteers — her name for the generation of adults who grew up watching Captain Planet — who had organically begun organizing around local environmental issues. In 1997, she used the proceeds from the Sasakawa Prize to create the Barbara Pyle Foundation to support those efforts, building a more cohesive network of environmentally motivated millennials. The network is currently working on an urgent messaging campaign for the upcoming COP26 climate negotiations in Glasgow to convince world leaders to take action. “It’s been 25 years already,” Pyle said. “We don’t have another 25 years.”

If Captain Planet were like any other superhero, now would be a really great time for a reboot. Climate scientists are warning that we have to act immediately to avoid planet-altering tipping points; the latest U.N. climate report hints that it may already be too late to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels; and anti-science sentiments are perpetuating the spread of a deadly global virus. We’ve identified the enemy and know generally how to defeat it, but we’ve so far failed to make that plan a reality.

There have been several attempts to make a Captain Planet movie, but the efforts always seem to stall out. Pyle says that may be due to outside writers’ misunderstanding of the show’s mythology. “I’ve heard, ‘He’s going to be an alcoholic and the Planeteers are going to find him somewhere in some old Irish bar in New York.’ Now, what is wrong with that premise? Captain Planet doesn’t exist without the Planeteers. He’s just a reflection of who we are.”

Boxer says he’s encouraged that pop culture is still talking about — and parodying — the show more than two decades since it left the air. But if he were to write new episodes for the show today, with so much uncertainty about our ability to act in the scientifically allotted time frame, he’s torn about how they would end.

“The jury is still out on what’s going to happen,” he said. “I think you’d have to go with ‘to be continued.’”