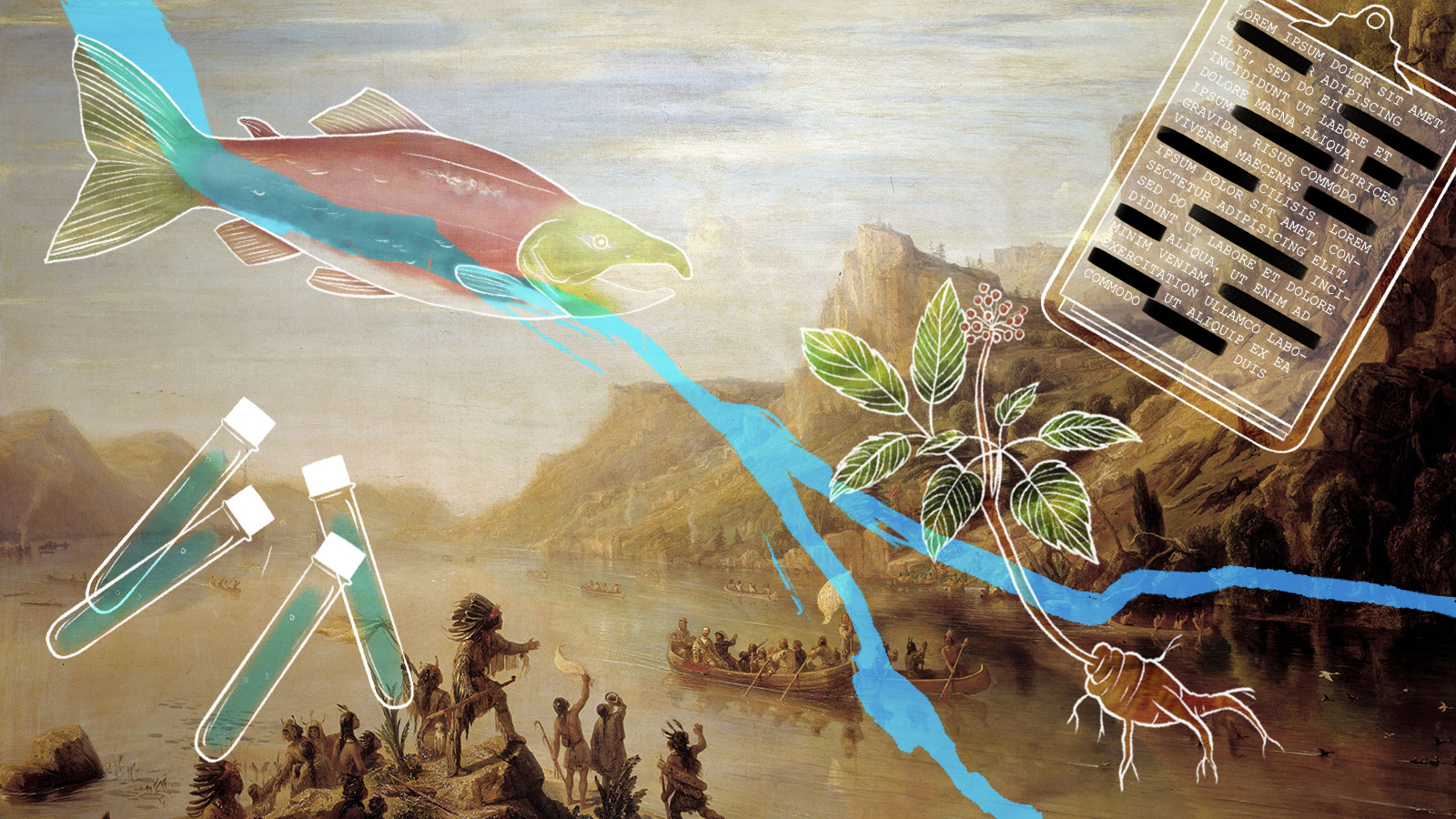

The Saint Regis Mohawk Reservation stretches for 25 square miles along the United States’ border with Canada. Akwesasne, as the land in Upstate New York is also known, translates roughly to “land where the partridge drums.” Nestled at the confluence of the Saint Lawrence River and several small tributaries, including the St. Regis and Raquette rivers, this ecologically rich environment consists of more than 3,000 acres of wetlands along riverbanks, islands, and inlets.

But the landscape can’t escape the encroachment of nearby pollution.

Tribal members live downstream from several major industrial facilities, hydro dams, and aluminum smelters. The Saint Lawrence has become an international shipping channel, and its sediments mix with heavy metals from old ship batteries and toxic chemicals from nearby Superfund sites. These pollutants have leached into the Saint Regis Mohawk way of life, shifting the range of flora and fauna on which many of their traditional practices rely.

The trash and toxic runoff are bad enough. They are killing off the tribe’s local fish population and medicinal plants. But now the Saint Regis Mohawk face another challenge: negotiating with the Environmental Protection Agency about how best to tackle these contamination issues while incorporating — and respecting — the tribe’s traditional knowledge.

Native communities are one of the groups most impacted by a changing climate — and many of the human activities that have precipitated it. They are also a necessary part of the solution, according to the newest Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) report.

Indigenous peoples comprise only 5 percent of the world’s population, yet their lands encompass 22 percent of its surface. Eighty percent of the planet’s biodiversity is on the lands where they live — and it may not be a coincidence. A significant part of traditional indigenous identity is linked to the natural world. “There is medium evidence and high agreement that indigenous knowledge is critical for adaptation,” the 2018 IPCC report states. And that’s due to their methods of managing forests and agro-ecological systems, as well as their traditions passed down through the generations.

Indeed, some in these communities believe that disseminating these traditions can help to address challenges, like climate change, that the world faces. But while the wider environmental community — and the rest of us — may benefit from gaining access to their knowledge, indigenous communities have no guarantee that their cultural values, secrets, and traditions will be respected if they offer it. That potential pitfall is prompting some Native Americans to question whether there is a way to share this knowledge that benefits the environment, as well as a tribe.

“It’s both a risk and an opportunity for indigenous peoples,” said Preston Hardison, policy analyst at the Tulalip Tribes Natural Resources Treaty Rights Office in Washington state. According to Hardison, many elders feel that they’d like to help the world heal, but they want their knowledge to be employed in the right way (without any sort of exploitation). For instance, sharing their knowledge about their land and how they use it could be employed to indigenous people’s detriment by limiting their access to it.

Even when the government taps indigenous groups for input, many of the resulting collaborations don’t show respect for the tribal people or the accumulated knowledge they possess. Take, for instance, in 2011, when the Saint Regis Mohawk received an EPA grant to create a climate adaptation plan for its natural resources — their animals, their crops, their medicinal plants. Initially, the EPA called for a plethora of scientific vulnerability and risk assessments to parse what resources were important for the Akwesasne way of life. But tribal members felt the testing was an unnecessary step to get to the heart of the issue.

“We didn’t need them to tell us what’s important to us,” said Amberdawn Lafrance, coordinator at the Saint Regis Mohawk Environment Division. “We already know.”

Ron His Horse Is Thunder, a spokesperson for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, looks over a river during Dakota Access pipeline protests in 2016. Robyn Beck / AFP / Getty Images

There are a lot of well-intentioned guidelines for asking indigenous groups to share their environmental knowledge with outsiders. The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples states that, if you do have access to these communities’ resources or knowledge, it should only be with their free, prior, and informed consent. In 2014, the EPA released a report with 17 policy recommendations for its work assisting tribal groups in protecting their health and resources. But the protocols don’t include requirements to forcefully protect tribal knowledge. Take principle seven, for example:

The EPA considers confidentiality concerns regarding information on sacred sites, cultural resources, and other traditional knowledge, as permitted by law. The EPA acknowledges that unique situations and relationships may exist in regard to sacred sites and cultural resources information for federally recognized tribes and indigenous peoples.

In other words, the agency will do its best not to disseminate sensitive tribal information relevant to environmental impact. But once tribal information is shared with a governmental body, it’s not always easy to keep it under wraps.

The Department of the Interior approached the Klamath and Basin tribes in 1995 when deciding how to allocate water rights in southern Oregon and northern California. Communities located in the Klamath Basin shared confidential information with the government about their fishing methods and other cultural practices in order to inform the decision. Then the Klamath Water Users Protective Association, a nonprofit group of farmers and ranchers in the region dedicated to maintaining irrigated agriculture filed federal Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests with the Bureau of Indian Affairs within the Department of Interior, demanding that the tribes’ responses be disclosed. When the agency refused, the association took them to court.

The Supreme Court concluded that if a tribe consults with an agency, most of the information provided during such consultations is subject to FOIA. (Hence the EPA’s “we’ll try our best” stance.)

“Ultimately, tribes face a Hobson’s Choice,” wrote legal scholar Sophia E. Amberson in a 2017 Washington Law Review article. “Risk disclosing proprietary information, or lose their seat at the environmental regulatory table.”

For many indigenous groups, losing control over anything from their traditional knowledge, dress, imagery, or even name is an all-too-common story. And it’s not always clear what, if any, legal recourse tribes have when they find themselves in those situations.

The clothing store Urban Outfitters landed in hot water in 2012 for selling “Navajo hipster panties” and a “Navajo print flask.” The Navajo Nation filed a lawsuit against the company, alleging trademark violation.

Although the technique worked, and the lawsuit was settled in 2016, there is some debate as to whether intellectual property is the best legal avenue to pursue when tribal knowledge is appropriated by outsiders. One big issue is that intellectual property rights expire. For example, if you publish a book, you typically own the rights to it for your lifetime plus 70 years.

“That’s a blink of an eye for indigenous peoples,” said Hardison of the Tulalip Tribes. “They’ve have had their knowledge since time immemorial.”

Unlike when they’re exploited by chain stores or sports teams, tribal communities stand a better chance to benefit when they share cultural knowledge for environmental preservation or cleanup. At the same time, indigenous people don’t want platforms like the scientists who contribute to the IPCC to become a giant knowledge-mining expedition for Native culture. “It should be about a true permanent durable relationship with indigenous peoples,” Hardison said.

Even though sharing suggests that both parties will also reap benefits, indigenous peoples are concerned the result will end up not meaningfully different from an episode of appropriation at the hands of Urban Outfitters.

In fact, once the indigenous knowledge gets outside of the local tribal community, there’s an increased risk for exploitation, said Gary Morishima, technical advisor at the Quinault Management Center just outside of Seattle. He said he’s heard of indigenous communities getting ripped off through informal sharing relationships. “[Outsiders] try to gain access to their knowledge and claim it as their own,” he explained.

Despite the risk, some indigenous advocates are pushing for tribes to share more of their wisdom more freely with environmental groups. “The time for secrets is done,” said Larry Merculieff, an Unagan tribal member based in Anchorage, Alaska, who is one of the biggest proponents. “There’s urgency because of the plight of Mother Earth. That includes climate crises, complete corruption, the abuse of women, abuse of Mother Earth-based cultures, and wars.”

To Merculieff that means giving outsiders unprecedented access to indigenous practices — even allowing them behind-the-scenes for sacred ceremonies and discussions, albeit via video. He is part of a group called Wisdom Weavers of the World — a gathering of what he likes to call “wisdom keepers” — which has produced 30 hours of films on Native knowledge.

The trailer for one of the group’s films features elders from all over the world meeting in Kauai for a discussion about the planet’s many woes. Against the backdrop of the Hawaiian island’s luscious greenery, they share instructions for how to live in balance and harmony with nature based on their own sacred traditions. Merculieff says these kinds of discussions are usually kept private, only accessible to those who are primed to understand them. But the elders in the film are now crafting a message to the masses about how their traditional wisdom can help address the world’s wounds.

“We are who we’ve waited for,” Merculieff says in the trailer for the film. “What we know is that the key to this mystery is simply to drop into your heart.”

Merculieff’s project is still raising funds. Though when it launches, Merculieff says he does not expect any pushback from other Native peoples. The government is not doing enough, he said when he chaired the indigenous knowledge sessions at the 2018 Global Summit of Indigenous Peoples on Climate Change. “We knew we need to establish our own ways of doing things.”

Back on the banks of the polluted Saint Lawrence River, the Saint Regis Mohawk tribe had come up with their own solution for climate adaptation. And they were pretty sure the EPA was not going to like it.

Rather than rely on risk assessments to come up with a strategy for the region, the tribe wanted to base their plan on a thanksgiving prayer, called Ohén:ton Karihwatéhkwen, which translates to “what we say before we do anything important.”

“We say it every day,” said Amberdawn Lafrance, the tribe’s environmental coordinator. The saying is so integral to the the Mohawk way of life that it’s the basis for other forms of community planning, such as developing school curricula.

Members created a list of natural resources that they’d prioritize based on what they’d always been thankful for. “We worked backwards,” Lafrance said. “We took the work that we’re already doing and we assigned it under each of the categories,” such as water, fish, and trees, needed to develop the climate adaptation plan.

The Saint Regis Mohawk tribe’s push to have more agency over their climate change plan was unusual, and some tribes are taking it a step further, explicitly spelling out the relationship between their knowledge and the EPA’s expertise. In these “bio-cultural protocols,” indigenous people can lay down in clear-cut terms how their local resources and knowledge should be managed prior to letting it be accessed by outsiders.

This practice greatly limits the scope of what entities can do with them. Tribes can stop governing agencies or other interested parties from commercializing their knowledge or resources wholesale. Contracts cementing these understandings are developed through culturally rooted decision-making processes within the communities. The Nagoya Protocol on Access and Benefit Sharing, an agreement closely linked to the Convention on Biological Diversity, bolsters these schemes, recognizing the need to acquire “prior informed consent” from indigenous peoples before using their knowledge.

These arrangements are used widely in South Africa. The Kukula traditional health practitioners of Bushbuckridge, South Africa, for instance, developed a bio-cultural protocol to address outsiders’ unauthorized use of traditional knowledge and overharvesting of medicinal plants. The contract lead to engagement with a local cosmetic company interested in using their traditional knowledge and establishing a medicinal plants nursery — all done on the Kukula people’s terms.

Kyle Powys Whyte, professor of philosophy and community sustainability at Michigan State and a member of the Potawatomi people, believes employing indigenous knowledge systems as part of our toolkit for dealing with climate change and advocating for Native rights go hand in hand.

“I wish that a lot of climate scientists would look at their statements that say that traditional knowledge is important and realize that, when they say that, they’re also saying that indigenous rights are important,” Powys Whyte said. “They need to be supporting what we need to actually strengthen our knowledge systems — not just share with others the information that we might have.”

Due to several centuries of exploitation, it’s difficult for tribes to come to compromises with government agencies. And while putting cultural practices to paper is one thing, getting government agencies to fully understand their value is another. For the Saint Regis Mohawk tribe, explaining their thanksgiving prayer-based plan to the EPA was a challenge — but it forced negotiations about confidentiality of the tribe’s cultural information.

“I think the EPA was trying to be considerate, but at the same time, it’s like they’re not considering all the implications of us letting that information go,” said Lafrance. She said a coworker tried explaining the sensitive nature of what they were sharing to officials over the phone, likening traditional knowledge to a grandmother’s coveted apple pie recipe. But Lafrance felt they “still didn’t get it.”

In the end, the agency agreed to take a backseat as the tribe got full rein of designing their climate adaptation plan to protect their resources based on their traditional teachings.

In fall 2018, Lafrance went to the 75th convention of the National Congress of the American Indian to speak on a panel about tribal climate change adaptation plans. The bulk of the discussion was about risk assessment data and how best to collect it. Then, Lafrance presented the Saint Regis Mohawk tribe’s completed climate adaptation plan that didn’t use a single smidge of data.

“I think that some people were shocked,” Lafrance said. “But some were proud of us for sticking to our guns — and knowing what’s important and who we are.”