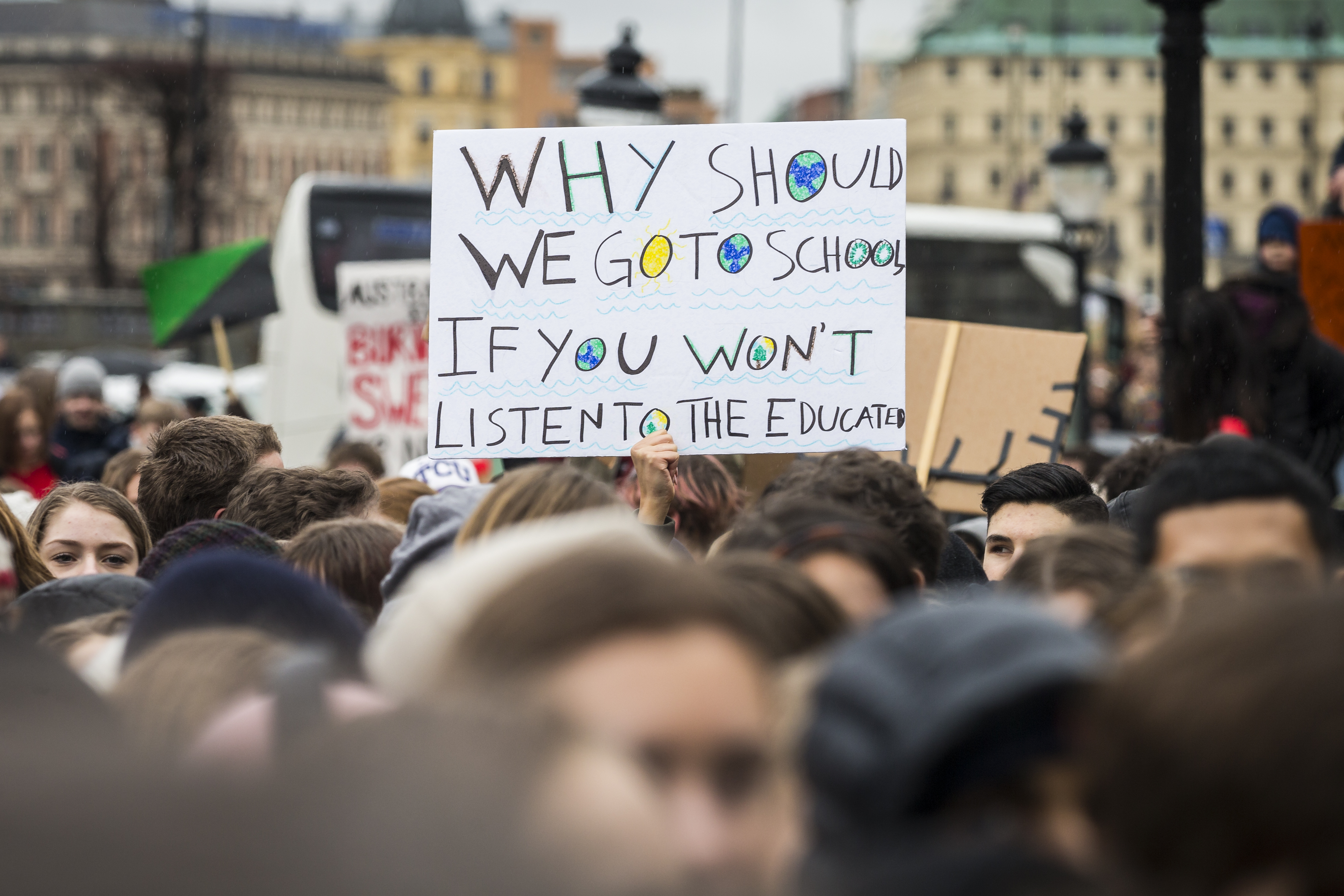

Last week, students around the world walked out of school to take a stand against climate inaction. In Portland, Oregon, a strike at City Hall turned into a 2-mile walk, briefly shutting down traffic across two major bridges and ending at… the skatepark? Voodoo Doughnut? Nope: the Portland Public Schools district office, where hundreds of kids sat in the parking lot, chanting and cheering in intimidatingly cool outfits.

Contrary to some curmudgeonly notions about the climate strike, students weren’t just taking advantage of an opportunity to skip school. In fact, many ditched class in hopes of learning more (cue the collective gasp from the Baby Boomers). Climate change is on teens’ minds, and they say their classrooms haven’t caught up.

Portland resolved three years ago to build climate literacy into public school curriculums, but 17-year-old Sriya Chinnam, one of the strike’s organizers, said the district hasn’t delivered: “We are demanding that they take charge and teach us about this climate crisis.”

The call for more climate change education has echoed worldwide, from Boston to Berlin. It’s built into the national Youth Climate Strike platform, which demands “compulsory comprehensive education on climate change and its impacts throughout grades K-8.” But while some educators and elected leaders are listening, there’s real debate about how — and whether — climate education should be built into education policy.

Connecticut Representative Christine Palm is among those who think lawmakers should play a more active role in climate education. She made news earlier this year when she introduced legislation that, if passed, would be the first law in the U.S. to explicitly require elementary schools to teach kids about climate change. (Her bill’s original language has since been folded into a larger act.)

“I would like to see the standards strengthened,” Palm said. “It needs to start earlier, and it can’t be optional.”

It may seem surprising that no state currently requires climate change education for kids of all ages. (I mean, I had to learn about Gonorrhea. What gives?) And in fact, while not every state makes the requirement as explicit as Palm hopes to in Connecticut — and none extend it to kids who still play with Jumbo Blocks — most states have standards that effectively requiring schools to teach about climate change.

Nineteen states, including Connecticut and Oregon, have adopted the Next Generation Science Standards (NGSS), a set of state-developed, research-based learning goals under which classrooms are expected to cover the topic starting in 5th grade. And every state in the nation (even Idaho, after a years-long legislative battle that ended early last year) includes some mention of climate change in classroom guidelines, according to the National Education Association.

But for Palm, the current law in Connecticut doesn’t create enough of a mandate. As it stands now, science instruction “may include the climate change curriculum” described by the NGSS, which theoretically opens the law up to interpretation by individual school districts. (For context: the same law instructs that safety instruction “shall include the safe use of social media,” and “may include the dangers of gang membership.”)

“To me, the problematic language is anything that is optional,” Palm said.

Branford, Connecticut high school teacher Amy Farotti said that specific legislation would “only strengthen” science education in her classroom, and it could be “a way to show school districts the importance of climate education.”

That’s especially important at a time when some lawmakers want to kill science-backed climate change education altogether. About two weeks after Palm introduced her original bill, longtime Connecticut Representative John Piscopo introduced a bill that would eliminate climate change curriculum from state law based on claims that the science is “controversial.” Similar bills have been introduced in other states. (What next? Geography curriculum written by flat-earther Tila Tequila?)

Not everyone in Connecticut thinks the changes are necessary, however. Although the law can certainly be read as optional, it’s not clear that school districts see it that way. In an interview with the Hartford Courant, Fran Rabinowitz, executive director of the Connecticut Association of Public School Superintendents, said that Connecticut schools already follow the NGSS standards: “If you’re a district in Connecticut, your curriculum is addressing it (climate change) already.”

There’s also some disagreement about how early climate change education should start. Palm and Youth Climate Strike both want kindergarteners to learn about climate change, but it might not be useful for kids that young, according to Frank Niepold, climate education coordinator for the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Association. Rather, young students should be given tools that will help them understand climate change when they learn about it later on, Niepold said. (NGSS standards suggest that kids start learning explicitly about climate change in 5th grade, although related instruction on the environment begins earlier.)

“You’re not talking about climate change in kindergarten,” said Niepold. “But what happens in kindergarten builds to 3rd grade, builds to 5th grade, builds to 7th grade.”

There’s a larger challenge, however: Teachers not knowing enough about climate change themselves. “Teachers feel pulled by their students to go into that space, and they’re not really very comfortable or ready,” Niepold said.

Rather than mandating that kindergarteners get lessons on climate change, Niepold says states could make a greater impact by funding professional development that equips teachers to address climate change when students are ready. Washington state is a good example: Last year, Washington dedicated $4 million to helping teachers gain the skills they need to teach the climate science outlined by the NGSS. (Governor Jay Inslee, who signed the legislation, has made the climate fight a big part of his presidential bid.)

Whatever the direction of future climate education legislation, Niepold hopes change happens fast. “The mismatch between what students need and the speed at which education tends to work is perhaps the biggest challenge [to climate change education],” Niepold said. “Even more so than the policies to stop it.”