Our planet reached another miserable milestone earlier this week: Sea ice fell to its lowest level since human civilization began more than 12,000 years ago.

That worrying development is just the latest sign that rising temperatures are inflicting lasting changes on the coldest corners of the globe. The new record low comes as the planet’s climate system shifts further from the relatively stable period that helped give rise to cities, commerce, and the way we live now.

So far, the new year has been remarkably warm on both poles. The past 30 days have averaged more than 21 degrees Fahrenheit warmer than normal in Svalbard, Norway — the northernmost permanently inhabited place in the world. Last month, a tanker ship completed the first wintertime crossing of the Arctic Ocean without the assistance of an icebreaker. Down south in the Antarctic, sea ice is all but gone for the third straight year as summer winds to a close.

The loss of Earth’s polar sea ice has long been considered one of the most important tipping points as the planet warms. That’s because as the bright white ice melts, it exposes less-reflective ocean water, which more easily absorbs heat. And that, sorry to say, kicks off a new cycle of further warming.

According to research published last fall, that cycle appears to be the primary driver of ice melt in the Arctic, effectively marking the beginning of the end of permanent ice cover there. The wide-ranging consequences of this transition, such as more extreme weather and ecosystem shifts, are already being felt far beyond the Arctic.

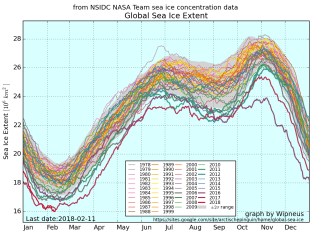

Data from NSIDC and NASA

There is just 6.2 million square miles of sea ice on the planet right now, about a million square miles less than typical this time of year during the 1990s, and a few tens of thousands of square miles less than just last year, which had marked the previous record low. This level of detail about the remotest parts of the planet is available thanks to our relatively newfound vantage point from space. Satellites monitoring the poles gather sea-ice data, and records only go back to 1978. But it’s a near certainty that ice levels have not been this low in a long, long time.

Proxy evidence from microscopic fossils found on the floor of the Arctic Ocean provides proof that sea ice levels there are the lowest in centuries and perhaps much longer. There’s evidence from ancient plant material in far northern Canada that the Arctic has not been as warm as it currently is for at least 44,000 years. For the Antarctic, sea ice is more variable and no reliable ancient reconstructions currently exist — though there’s convincing evidence that there was less sea ice there about 128,000 years ago. For context, humans first mastered agriculture about 12,000 years ago in the Middle East, once temperatures stabilized near the end of the last ice age.

The middle of February is the usual time of the annual low for the planet’s sea ice (the Antarctic almost always has more ice than the Arctic, because there’s less land mass in the way); lately, however, the February lows have been much lower than normal on both poles. The Arctic and the Antarctic mostly operate as separate entities in the Earth’s climate system, but at the moment they’re in sync — a bit of a puzzle for researchers.

According to Zack Labe, a sea ice researcher at the University of California-Irvine, thinks there might be more than one cause. Arctic sea ice has been declining rapidly for decades, which Labe and other scientists are sure is the result of human-caused warming.

Antarctic ice, by contrast, began falling in 2016, which suggests the drop could be connected to natural swings in the climate. “It is too early to say whether losses in the Antarctic are representing a new declining trend,” says Labe.

Although the loss of sea ice is troubling, the overall pace of change is even worse. Global temperatures are rising at a rate far in excess of anything seen in recent Earth history. That means, in all likelihood, these latest records were made to be broken.