It’s Thursday, October 29, and South Korea is the latest country to promise to go carbon neutral by 2050.

![]()

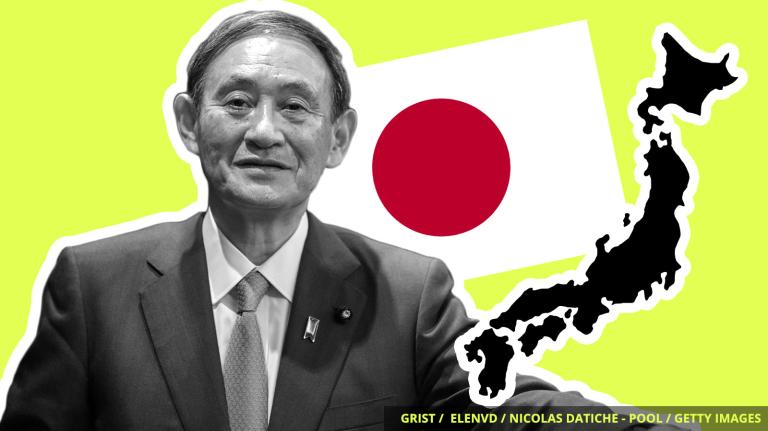

Last month, China pledged to zero out its carbon emissions by 2060. Earlier this week, Japan promised to do the same by 2050. Now, South Korea has jumped on the net-zero bandwagon, pledging to become carbon neutral by 2050.

“Together with the international community, we will actively respond to climate change and target carbon neutrality by 2050,” South Korean President Moon Jae-in said in a speech on Wednesday.

The path to carbon neutrality for the country includes putting more than 1 million electric vehicles and about 200,000 hydrogen cars on the road by 2025. Moon’s plan also includes creating urban forests, boosting recycling, and remodeling public buildings to run on renewable energy.

Moon was reelected in April on a platform that included a Green New Deal to slash emissions and create jobs. Moon unveiled the details of his $35 billion Green New Deal in July, but that proposal fell short of setting a deadline for phasing out emissions.

Currently, South Korea generates less than 6 percent of its electricity from renewable sources and 40 percent from coal. The country declared pollution a “social disaster” last year, and youth activists sued the South Korean government for inaction on climate change in March.

The Smog

Need-to-know basis

Hurricane Zeta made landfall as a Category 2 storm about 65 miles southwest of New Orleans on Wednesday afternoon, packing maximum sustained winds of 110 miles per hour. The storm killed three people and knocked out power for more than 2.5 million people in Louisiana, Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Mississippi, and Alabama.

![]()

On Thursday, the Trump administration officially opened the door to logging and road construction in 9 million acres of Alaska’s Tongass National Forest. Alaskans largely opposed eliminating Clinton-era protections for the nation’s largest national forest, but Alaskan elected officials have been needling the federal government to lift restrictions on Tongass for years.

![]()

A study published this week in Science Advances contradicts the long-held assumption that a sturdy layer of permafrost underpins much of Alaska. The study found that there’s hardly any permafrost under the seafloor on the state’s northeastern coast, which means that the permafrost that is there could melt, and release its carbon into the atmosphere, much faster than previously assumed.