Integration is a good thing, except when it comes to trash, says Melanie Scruggs, the Houston-based program director for Texas Campaign for the Environment. Scruggs’ organization is part of the Zero Waste Houston Coalition, which is campaigning against the city government’s new “One Bin for All” proposal, which would have residents place their garbage and recyclables in the same trash can for collection, to be separated by workers later.

This idea, funded with a milli from Bloomberg Philanthropies, is different than your run-of-the-mill recycling separation factories. Those “materials recovery facilities,” as they’re called, separate recyclables from one another — your glass from your plastic, for example — as our columnist, Umbra Fisk, has explained. No, this plan would allow you to toss out the leftover scraps from the hotbar in the same container it came in, along with the snotty tissues, the jammed-up glass, and the nasty plastic altogether, to be unyoked later at facilities that the Zero Waste Coalition call “dirty materials recovery facilities” — or “Dirty MRFs” for short.

The “One Bin” plan sprang from the city’s Office of Sustainability. Despite declaring itself a green city, Houston’s recycling rates were running around 14 percent; compare that to San Francisco, which has managed to recycle 80 percent of its waste. The One Bin plan aims to bump Houston’s recycling rate up to 75 percent.

But the plan arises at the same time that Houston Mayor Annise Parker committed last October to expanding recycling bins distribution throughout the city. Before that, fewer than half of the city’s neighborhoods had the bins. That move was applauded by environmentalists around the city. But they’re now scratching their heads about how city-wide recycling bins will co-exist with a one bin fits all strategy, and are doubtful about the landfill diversion goals.

“No other facility like this has ever achieved anything close to what our recycling goals are in Houston — and most have been outright disasters,” Scruggs said in a press statement earlier this month. “City officials have set a 75 percent recycling goal for this proposal, but when we researched similar facilities, none have ever exceeded 30 percent. It’s been shown over and over that real, successful recycling will never be possible if the city tells residents to mix their garbage with recyclable materials in the same bin.”

You can read about the coalition’s research in the report “It’s Smarter to Separate” (not to be confused with a Stormfront post). The report not only takes aim at the “one bin” approach, but also another part of the plan, which would incinerate some of the garbage and convert it into fuel. It’s the same “waste-to-energy” experiment that’s been attempted and halted in Baltimore, and cancelled in New Orleans. The coalition also points to an Energy Information Administration report that figures this kind of energy production is more expensive than producing energy from nuclear sources, leading the coalition to the conclusion that “waste to energy is a waste of energy.”

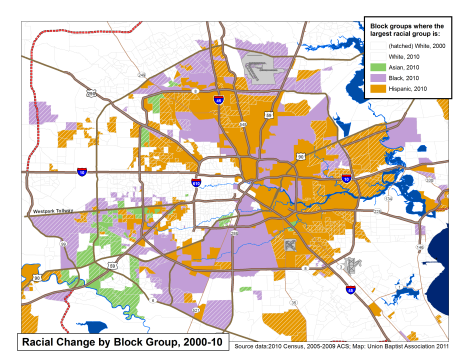

The coalition also senses a whiff of environmental racism in this deal. The areas slated for Dirty MRFers fall mostly in black or Latino communities — which is a shame, as Houston is one of the most racially diverse cities — and now the city has an environmental justice issue on its hands.

This is why the Houston branch of the NAACP is involved, as is the pioneering environmental justice scholar Robert Bullard, whose first research study in 1979 was on the siting of waste incinerators and garbage transfer stations in Houston’s black neighborhoods. The study was ammunition for a lawsuit against the city for the permitting of a waste facility in a black community that the residents did not want, and it’s considered a major jump-off point for the environmental justice movement.

Here they are almost 40 years later still fighting the same battle — against using black and brown neighborhoods as garbage projects.

“Bad proposals like incinerators and landfills have a way of uniting communities against a known threat to their health and safety, not to mention the safety of the workers in the facility who would be sorting through Houston’s trash,” said Bryan Parras of Texas Environmental Justice Advocacy Services (T.E.J.A.S), a member of the Zero Waste Houston coalition.

The worker issue Parras references is a nasty proposition alone. The report provides a few anecdotes from workers who toil in similar facilities in other cities. This particular one comes from a worker in a Chicago trash separation plant … ugh:

“There are so many smells that you come across, they make your stomach queasy. Yet before we went to work, they showed us a safety film where all the stuff was really clean… They told us that it was going to be a clean environment. They said fresh air was going to be pumped through there every 15 minutes, so it wouldn’t smell, and stuff like that, but it wasn’t. It was a little different than they had described it. One time they had a dead dog… go through there. There was all garbage, you know (not just recyclables). At first we thought they were only talking about plastic bottles and cans going through there. But that was plain garbage, everything, you know? Dirty diapers, cleaning products, stuff like that.”

I can’t remind us enough that Martin Luther King’s last campaign was for improving the conditions of sanitation workers in Memphis — a campaign that Bullard says serves as the true genesis of the environmental justice movement.

Given Houston’s “One Bid” plan is a public-private partnership, it could displace a number of city employees, said Scruggs. Not to mention, the city is offering around $100 million of its own money in tax incentives if it passes (it’s still at the bidding phase and the city council would have to approve the contract). I can only think of the city I grew up in, Harrisburg, Pa., that went bankrupt for wheeling and dealing with a similar incinerator scheme. Detroit, meanwhile, owes much of its bankruptcy to an incinerator project also.

If that ain’t all bad enough, these plans can be ruinous for climate. The report cites an EPA study stating that “36.7 percent of the greenhouse gas emissions produced in the U.S. are produced by the materials production, consumption, and disposal cycle.”

There are no easy answers when it comes to our waste disposal. The most ideal is to find ways to consume less, and dispose of less waste, through composting, reuse, recycling, remixing and any other re-[x]-ing you can think of.

I can see how a one-bin-fits-all plan would appeal to the laziness in us — but Scruggs says she has 20,000 signatures from Houston residents that says otherwise. They want to keep their reusable trash apart from the disposable. I can see how incineration helps solve the landfill problem, but if it worsens the climate and environmental implications of waste management, then it seems like a wash. Justice is not disposable and need not be separated from the equation.