Last week, when members of Congress introduced legislation to “fix” the part of the Voting Rights Act that the U.S. Supreme Court decided was broken last summer, it was inspiring to see one environmental leader, Sierra Club President Michael Brune, standing behind civil rights groups.

“It is vitally important that members of both parties in Congress are acting to secure one of the most fundamental of all American principles by focusing on updating the Voting Rights Act,” Brune said. “This well-intentioned bill to do that is a start, but we share the concerns of our partners and allies at the NAACP that some aspects of this legislation fall short of protecting the voice of every American at the ballot box.”

Brune nailed it. He understands that the right to vote is more than just a civil rights problem. Until that fundamental right is guaranteed for all, the wealthy elite will craft policies that determine whether the environment is considered in our policy decisions — and that, as I’ve written before, is a recipe for disaster.

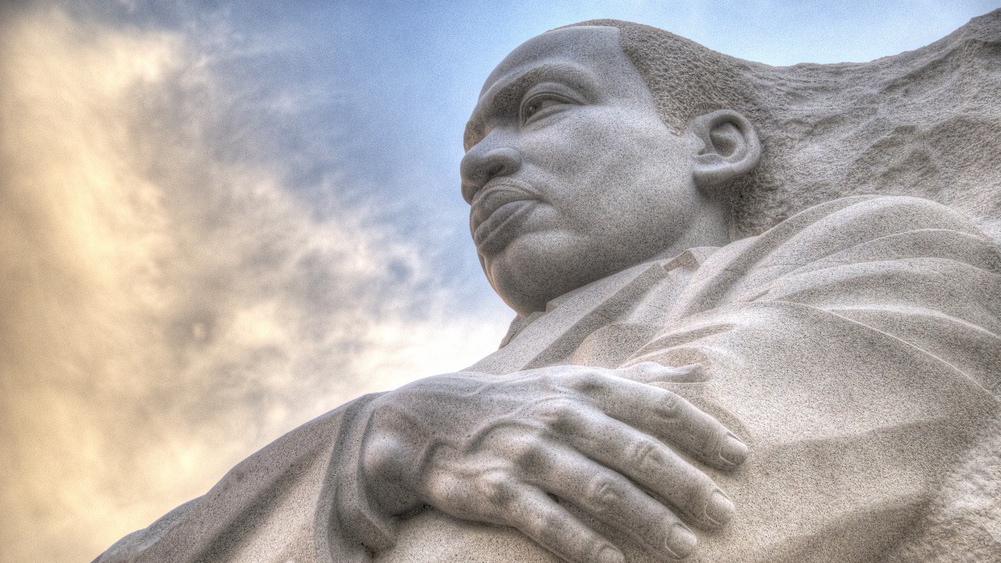

Today, the day we commemorate the life and work of Rev. Martin Luther King, I only wish that more non-NAACP-allied groups had spoken up on this. I’ll get back to that in a moment. First, a little background on the Voting Rights Act legislation.

Last summer, the Supreme Court dismantled “Section 4b” of the Voting Rights Act, which created the formula for determining which states and jurisdictions would need to submit new elections rules to the federal government for screening to ensure they wouldn’t abridge people of color’s voting rights. It just so happens that the formula swept up a lot of states that I recently indexed as having the worst health, environmental, and civil rights records in the nation.

The federal screening process, “Section 5,” was considered the cornerstone of the Voting Rights Act for its ability to weed out racist elements of election laws, even those planted unintentionally, saving states and counties from lawsuits while preserving the “one man, one vote” principle for all Americans. It had been saving America from the worst of election administration decisions that could have disenfranchised millions since the late 1960s. But last summer, five Supreme Court Justices — four white men and Clarence Thomas — declared Section 4b unconstitutional, saying it clung too hard to the racism of pre-1960s America and needed updating.

That update is the amendment introduced last week, which proposes a new formula that, among other things, would rope states guilty of five or more civil rights voting violations over the past 15 years into Section 5 screening. A voter ID law would not count as a violation, despite the fact that both the U.S. Justice Department and a federal court found that one in Texas would have disenfranchised hundreds of thousands of Latinos and African Americans — that was in 2012, not the 1960s.

Civil rights organizations unanimously applauded the amendment, but many expressed disappointment about the hall pass given to voter ID. This is no small sticking point; a recent study from University of Massachusetts sociologists found that voter ID laws were introduced in states where population and voter turnout for people of color had increased since Obama was elected president. These laws are clearly designed to keep people of color away from the ballot box.

As refreshing as it was to hear the Sierra Club’s Brune standing behind the NAACP, I was disappointed that more green leaders didn’t speak up. It brought to mind Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in his post-“Dream” years, when he was rejected by black and white liberal groups alike.

His speeches attacking materialism, mandating special treatment for African Americans, and exposing the squalid conditions of urban slums made him the scorn of many calling themselves “progressive.” He probably didn’t know that his unpopular work, like organizing garbage truck workers in Memphis, was a jump-off for the environmental justice movement, as its chief historian, Robert Bullard, often reminds us. I call this work King’s last, scarred, spangled banner, waved before his murder.

Many African-American civil rights activists at the time shunned ideas around building a new movement based on the environment. There was fear that it would divert attention and resources away from their unfinished business with dismantling racism. In many ways, their fears were later confirmed. But as I discussed in one of my first blogs here, many of the 1970 Earth Day organizers were unafraid to confront these intersections, like activist Channing Phillips, who said his participation was “out of a deep conviction that racial injustice, war, urban blight, and environmental rape have a common denominator in our exploitive economic system.”

Those were also common numerators with Dr. King’s “giant triplets of racism, extreme materialism, and militarism,” which he revealed during his anti-Vietnam War speech in late 1967, when he was approaching his darkest days of isolation from the “liberal” movements. King defined racism as “a philosophy based on a contempt for life,” but was sinking into depression as he realized that many of those he thought were his colleagues in the left were growing either more silent on the issue, or were succumbing to it.

In his 1967 book Where do We Go From Here?, King excoriated his white comrades, demanding they step up on the racial justice front. “In spite of the hard reality that many blatant forms of injustice could not exist without the acquiescence of white liberals,” he wrote, “the fact remains that a sound resolution of the race problem in America will rest with those white men and women who consider themselves as generous and decent human beings.”

This sounds like Amiri Baraka warning you that your nation is doomed unless you bridge racial and class divisions, and also like King telling Alex Haley that America’s destiny is “tied up in what answer will be given to the Negro.” Today, this means following Michael Brune, who is following the NAACP, which is unfollowing energy apartheid, which does not follow with the justice philosophies of Nelson Mandela, nor the freedom philosophy of Solomon Northrup. It means you can’t burn trash next to a school in a Baltimore neighborhood already burned by poverty, or build one over an old landfill in New Orleans, and not expect residents to rise up. It means you can’t have your retreat at a Southern plantation. Nor can you pave over a historic, black community in Mississippi for your shopping plaza, or allow wealth to run elections so you can burn more dirty coal.

It means you have to speak up for voting rights for everyone, no matter what your central mission is. It means you support King as much in his depressed, scarred state as you do in his Dreamy state.

It means environmental protection is civil rights, or else none of the above matters. It means some of these green groups have to start acting like the “NAACP for the environment” they were originally funded to be. It means you know and follow Damu Smith, Hazel Johnson, Kim Wasserman, and Peggy Shepard like you do John Muir, Jane Jacobs, and Al Gore. It means King was speaking the truth when he said, “The Negro revolution is a genuine revolution, born from the same womb that produces all massive social upheavals — the womb of intolerable conditions and unendurable situations.”