This story is part of Grist’s Coming to our Senses series, a weeklong exploration of how climate change is reshaping the way we see, hear, smell, touch, and taste the world around us.

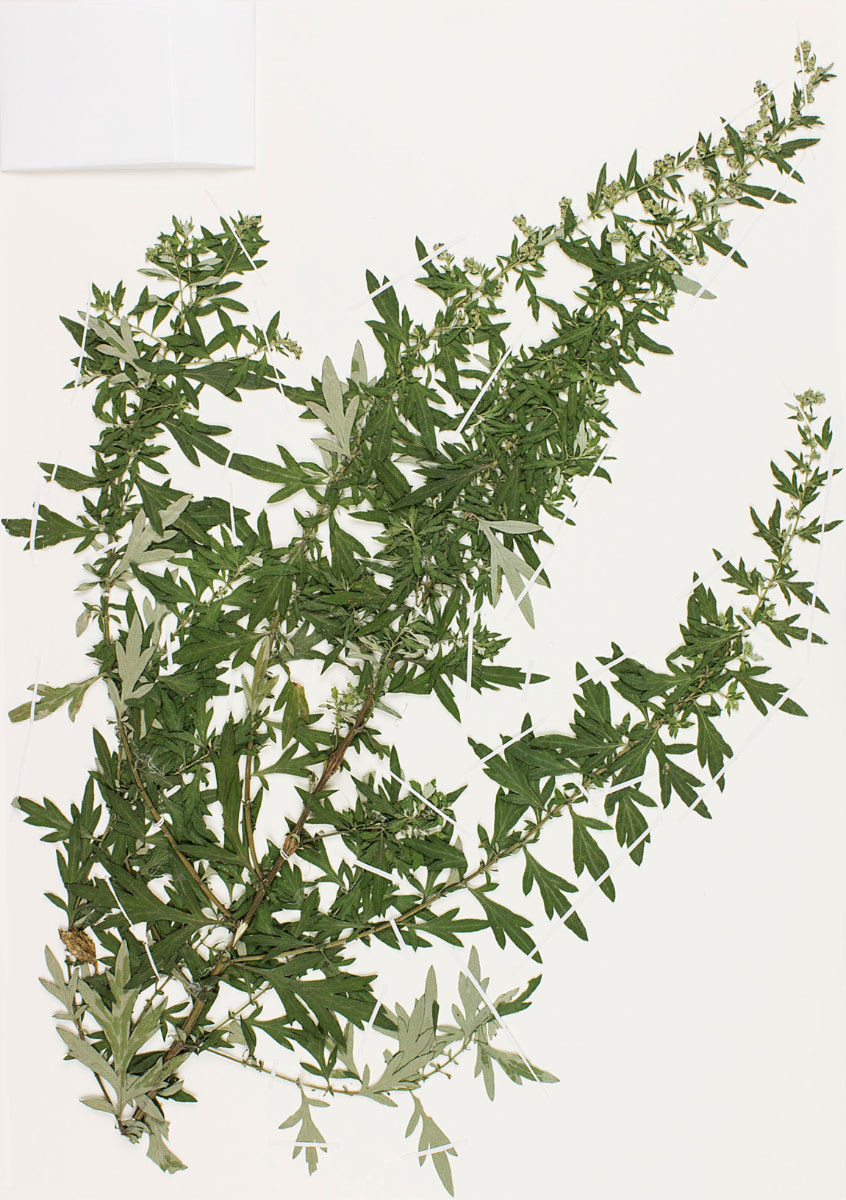

The first time I saw mugwort, I slipped and fell down a hillside in my haste to get to it, but my excitement was mislaid. I was on an edible plant tour of Central Park, guided by veteran forager and cookbook author Marie Viljoen, chasing new flavors to add to my practice as a Chinese cook. I spotted frilly green leaves and rushed to them, believing them to belong to the prized Chinese cooking green, crown daisy. But as I crouched in the dirt, post-tumble, Viljoen explained my error. Mugwort belongs to the Asteraceae family that includes crown daisy and sunflowers, and it shares some physical characteristics with its relatives. It also originally came from the Eurasian continent, where it is used culinarily and medicinally in many cultures, including in China.

Something about the plant and our shared ancestry captivated me. I thought I had a good understanding of important Chinese culinary herbs, yet here was one I’d never encountered, much less expected to find in the middle of Central Park. Nibbling the edge of a raw leaf, I tasted the rosemary and sage notes that Viljoen promised, plus a distinct minty bitterness of its own.

Later that summer, I gathered mugwort seeds in the hope of using them as a spice. The tiny, fuzzy nibs shared prime space on my counter with my soy sauces and black vinegars, but they went largely unused. I didn’t have a good handle on how to incorporate those powerful, feral flavors. Meanwhile, with my newfound ability to identify a few local plants after Viljoen’s lesson, I saw mugwort at every turn throughout the city: lining every sunny walking path in every park, pushing up out of the margins along the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway, gathering festively around sidewalk trees. I was determined to eat more of it.

Two years later, I found myself climbing over a ragged chain-link fence to get to a patch of unsullied mugwort on Brooklyn’s East River waterfront. In the time since my lesson in Central Park, my interest in foraging had become obsessive. I’d spent hundreds of dollars on obscure ethnobotany books, and paid hundreds more in parking tickets in my relentless pursuit of certain plants. I’d learned the names of dozens more species, and in so doing, realized that New York is as diverse botanically as it is culturally. And I’d learned to avoid foraging around dog pee, busy roads, and Superfund sites — hence the fence-hopping.

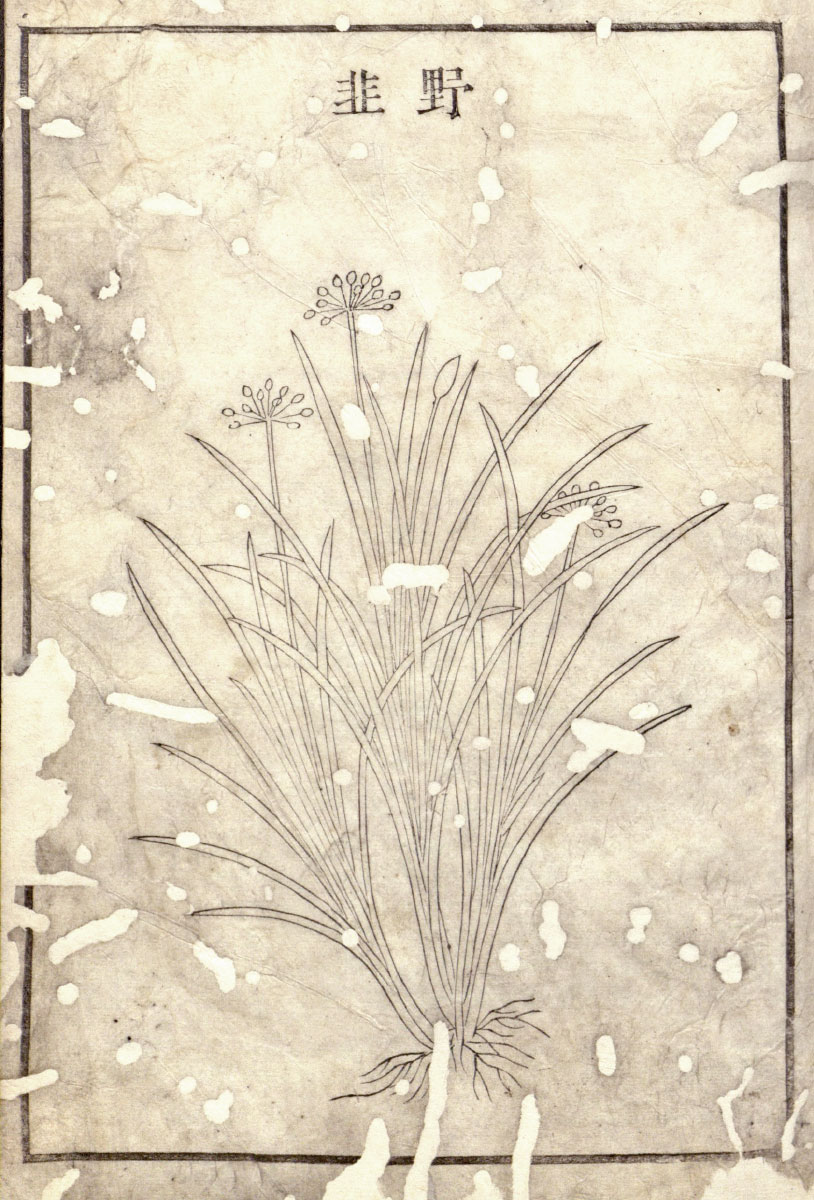

The specific mugwort agenda that had me trespassing on this particular April day was to see whether I could recreate a traditional Chinese recipe from scratch — Qing Tuan, or mugwort rice dumplings. They’re traditionally eaten as part of the Qing Ming holiday in April, when Chinese people gather at burial grounds to sweep ancestral tombs and lay food offerings. Mugwort in early spring is tender and baby-green, and when blanched, pulverized, and squeezed, it produces emerald-toned juice that dyes the rice dough and imparts it with a subtle herbal fragrance. It is one of my people’s ways of taming the plant.

It feels like a blessing to learn the stories of fellow immigrants. I left my hometown, Nanjing, too young to have learned its natural landscape, but in Queens I found Toona sinensis, a tree that produces feathery baby shoots with an addictive sulphuric onion fragrance. Its harvest season is even more fleeting than ramps’ — once the leaves are mature, they lose their fragrance and become tough — and in Nanjing, they are just as treasured. The trees in Queens were too tall for me to reach their baby leaves, but I didn’t mind. My consolation prize was learning that these giants were planted as part of New York’s first exotic plant nursery, and therefore they are possibly the oldest T. sinensis trees in North America. With Viljoen’s help, I identified the obscenely red summer berries all around Fort Tilden as Nanking cherry. Their perfect sweet-tart flavor was only matched by my pleasure in discovering that they were first planted in the United States in Boston’s Arnold Arboretum, which is also the first place my parents took me foraging when we arrived in the United States.

All of these plants from home seemed to say, “Welcome, old friend. It’s OK that we didn’t meet before, we’re both here now.” And they also invited me to dig deeper. The more plants I was able to identify, the more I wanted to know how each came to be where it was. And as I entered my third foraging season, the questions multiplied: Why was the cherry harvest so abundant last year, and so paltry this year? Was it climate-related? Was the mugwort truly spreading year over year, or had my growing appreciation for plant life taught me to better see abundance?

Foraging, which had started out merely as a quest for new flavors, had become an entirely different sensory pursuit. I understood my ignorance as that of a child learning language. We teach children to identify the color blue, and that the sky is blue. But somewhere between my ancestors and me, we stopped teaching children to identify a plant by name, to pick it out of a patch of other plants, to know when it grows, what it smells like, and which parts of it are medicine, poison, or food. I wondered, even if I foraged for the rest of my life, if I could ever regain all the knowledge that was once common sense to my ancestors, and whether it’s been irretrievably lost — an internal almanac unwritten.

But then again, maybe my city — my adopted habitat — was already too jumbled up to make sense of, with all seasonal patterns and interspecies relationships having been disrupted by hundreds of years of intercontinental migrations, both human and botanical. I only knew that in a year of climate headlines, when the floods started in early summer and culminated with multiple people drowning in their homes in September, foraging could not be an innocent practice.

Each new plant is a portal, I learned, and their stories are as complicated as our own, because they’re so tied up with our own. I’d come to this East River embankment because I’d noticed that while mugwort does well in any high-traffic area, it seems to thrive at the salty edges of the city. When I tugged on this thread, I learned that it first spread across the Atlantic in the soil ballast that kept colonial ships stable on turbulent seas, some very likely bearing enslaved people. That transported earth was then poured out to fortify the landfills that extend the city into parts of the East River, including the spot where I stood. Just as there is no New York City without slavery, there is no New York City without this centuries-old ballast and all the foreign life it contained.

Back at home, I prepared the Qing Tuan as an offering for both my ancestors and the many people whose forced migration here likely brought this mugwort. I thought about this cipher that has traveled the world, swept along on grandiose and terrible human projects. Europeans know mugwort as wormwood, which famously gives absinthe its hallucinogenic qualities. In some Indigenous practices, mugwort is known to induce vivid dreams. In China, we prepare this plant as an offering to the spirit world. Mugwort clearly likes humans, and it accompanies us in times of great disruption. Perhaps it does so to guide our subconscious, all of us who are where we are because of displacement and resettlement, trying to weather the coming storms.

If sensory awakening is followed by sensemaking, maybe moral responsibility is what follows. First I learned how to see, name, taste, and remember the plants, then I learned their stories, and then it became clear that what we do with their heavy histories and contested habitats is intricately tied up with our own futures. As foraging has never been more popular with city-dwelling foodies, I am acutely aware of my own position in this new wave of neophytes, and deeply unsure whether our new hobby — fundamentally an act of taking — is a Good Thing. Foraging has been lauded as essential to being in tune with one’s environment; the keystone of eco-conscious eating; and the path to ingredients of “true quality and integrity,” to quote a San Francisco Chronicle article about Alice Waters’ go-to forager.

But even if we only harvested invasive species, it seems foolish to assign a whole lot of virtue to picking some weeds at a time of environmental crisis. I can see how easily foraging, especially urban foraging, could become just another liberal affectation, like obsessing over paper straws. But then, what power do we have? What responsibility do we have?

I shared my doubts with Candace Thompson, park manager of Stuyvesant Cove Park, one of only two New York City parks that allow foraging, and the artist behind the Collaborative Urban Resistance Banquet. (The tagline for said project is: “Adapting to climate crisis by meeting [and eating] our non-human neighbors.”) I ask her if it’s possible to eat an ecosystem back into balance.

“I would rescind the word ‘back,’” she says, “Nothing goes back — it’s only moving forward. I think there are very grassroots, local-economy ways for folks to be making use of the abundance around them — making kudzu baskets, eating garlic mustard.”

Does that mean they could eradicate all these weedy non-native species? “No,” she says. “But should that be your goal? Maybe not.”

I like Thompson’s framing of abundance as a mindset that encourages gentle personal use rather than frenzy. I have seen what happens when a weed is no longer a weed. Around the same time of year that I harvest ignored and maligned mugwort, foraged ramps are sold for up to $25 per pound in New York City. The first time I tasted one, I thought, “All this for a fucking onion?”

Stumbling across a pristine mountainside of ramps is magical, but to me, it’s no more so than the waving fields of mugwort at our shores, nor any other weed growing abundantly in the humblest of settings. And yet ramp populations in the Northeast are becoming more threatened each year, thanks to swooning portrayals from chefs, food writers, and Martha Stewart herself. Over the past couple of decades, abundance has turned to scarcity, which begat more scarcity in a market that assigns value to exclusivity.

I only got to meet Tama Matsuoka Wong in person because this year’s ramp harvest crashed. Matsuoka Wong is a “meadow doctor” and professional forager who supplies many of New York City’s best restaurants with immaculate ingredients foraged with permission from land trusts and conservancies. On a day when she was supposed to be gathering ramps, I visited her at her home.

On one pink-stemmed bunch of ramps, she showed me the telltale signs of the allium leaf miner, a rapidly spreading fly from Europe whose larvae feed on alliums. The first sign of infestation looks like a powdery white fingerprint at the edge of a leaf. Then the white turns black and eventually eats holes into the leaves, rendering them blotched and unsightly. The leaf miner attacked all of Matsuoka Wong’s ramp spots this year, which means for the first time in over a decade of professional foraging, she had no product for her chefs. Standing in her kitchen, we made ramp leaf dumplings from the damaged leaves. They tasted just fine, but both of us knew they weren’t fit for sale.

Given how little is known about the leaf miner’s impact on wild alliums, Matsuoka Wong is deeply concerned for the future of ramps, and she has already started conducting her own experiments and working with farmers and researchers. Climate change is a likely factor in the pest’s spread, as warming has made more parts of the world hospitable. I ask her how she sees her role as a land steward given the deep disruptions both behind and ahead of us.

“It’s about balance,” she says, echoing Thompson. “It’s kind of like our country: People come, and that’s OK as long as someone isn’t bullying someone else. When I see a plant that is way over-dominant, I’m not trying to eradicate it, I’m just trying to manage it so that they are not completely suffocating the other plants.” It is hard to square her words with our country’s history of violently squandering opportunities for balance among Native peoples and newcomers, but I want to believe in her optimism. And as a foreigner on this stolen land myself, I want to believe that there is a transformative ecology that doesn’t involve totalizing concepts like native vs. invasive, rescue vs. eradicate.

At the southern tip of Staten Island is Conference House Park, named for a failed peace conference between the British and the rebel American army. It’s a place where the painful layers of New York history, deliberately paved over throughout most of the city, are all out in the open. Beneath the ridgeline where the Raritan Lenape buried their dead with feet pointing toward the water, the land drops into a sandy sweep before narrowing at the “south pole” of New York State. The Lenape shaped the land here by harvesting fish and oysters and mussels from the ocean. Their middens calcified the soil, allowing useful trees to flourish: hackberry, black walnut.

Beyond Burial Ridge and the shell-strewn shore, you can see the big ornamental Osage orange trees planted when this land was intended to be an extension of the prosperous settlement of Tottenville, before the city acquired it in 1926. In the foreground, a car-sized piece of concrete dropped by Hurricane Sandy has yet to be cleared away. This beachfront was once a mixed forest, and as hardy foreign creepers like oriental bittersweet moved in and choked off the trees, the soils became prone to erosion. Native grasses, like American beachgrass, have been replaced by mugwort — the healthiest patch I’ve ever seen.

John Kilcullen, the park director, invites me to forage from the park, and I go home with the tenderest young plants I can find. My plan is to make mugwort tempura, thanks to a line I came across in Tama Matsuoka Wong’s cookbook, Foraged Flavor. Deep-fried, the leaves fan out proudly in oil and hold their magnificent shape. Most amazingly, the frying transforms a skunky herb into savory vegetable, melting away all aggressiveness. This is it. This is the recipe I had been searching for.

If we wanted a marketing campaign to get everyone eating mugwort instead of ramps, mugwort tempura would be at the heart of it. Yet when Matsuoka Wong tells me that Masa, the sushi restaurant in Manhattan where meals start at $750, serves mugwort tempura, I am only filled with apprehension. Maybe as the allium leaf miner might be warning us about ramps, telling us to stop turning an abundant weed into a coveted commodity, it’s also telling us not to make the same mistake with mugwort. Foraging while blindly following well-intentioned advice — only harvest “invasives,” only take one leaf per ramp — is to remain ignorant to the full stories of these plants, which in turn comprise the full scope of all that this land is and was. The real illness in our ecosystem isn’t so many foreign roots and rhizomes, it’s the idea that we can heal it through the tactics of consumption and capitalism.

I find myself envying both Thompson and Matsuoka Wong for their access to clean land — not only for the food that grows on it, but for the privilege of being able to shape the ecosystem. All the parking tickets and fence-hopping have taught me that foraging is a constant negotiation of property laws, many of which were implemented to exclude Black and Indigenous peoples from the land. Today, foraging is not allowed in most New York City parks, national parks, and of course, private property sans permission. And if taking is difficult, giving back can be even more so: Viljoen took the initiative last year to “guerrilla garden” a neglected and barren strip of a city park near her Brooklyn home, only to find the seedlings completely uprooted and removed shortly thereafter.

Active land stewardship, once practiced by every Lenape person who foraged on the mid-Atlantic coast, has been professionalized (in the case of public parks) or limited to the few (in the case of privately held properties). I’m far more connected to this land than when I first started foraging four years ago, attracted to the idea of new flavors, but only because I’ve repeatedly broken a lot of property laws that people in other bodies may not be able to get away with.

So I am still trying to figure out my role here. I asked Viljoen what she thinks foragers can do, ultimately, to be better stewards, especially those of us who live in heavily demarcated and policed urban environments. She framed it in terms of education: “Learn not just the edible plants, but the ones that grow around it, how they interact, what they each need. Learn how to ‘read’ a whole landscape rather than focusing on the one thing you can take.”

I’ve come a long way since tumbling down a hill to score what I thought was free food. At another of the city’s edgelands, I read the landscape: I see mugwort bordering paths mown by humans. Behind its lacy leaves, phragmites stand tall in sunny spots and riotous Japanese honeysuckle extend from more shaded areas, the trees above them barely visible through thick mats of oriental bittersweet vines.

I have learned to see this as a violent scene. This area was once likely another hybrid forest, and now there are hardly any native trees and shrubs left thanks to each of these rigorous transplants from Asia. This is an ecosystem out of balance, but I also now know that these plants are here because I’m here, and I’m here because they’re here, each of our paths to this spot set in motion long ago by forces outside of our control. And despite what certain forces want now, none of us can be removed from this land, so for now I ask the plants — all of them — to continue teaching me what mutual transformation can look like. We meet the rising waters together.