Five hurricanes made landfall in the United States this year, causing half a trillion dollars in damages. Flooding devastated mountain towns along the East Coast. Scores of wildfires burned almost 8 million acres nationwide. As such events grow more common, and more devastating, homeowners are seeing their insurance premiums spike — or insurers ditch them all together.

An analysis released Wednesday by the Senate Committee on the Budget found that the rate at which insurance contracts are being dropped rose significantly in recent years, particularly in states most exposed to climate risks. In all, 1.9 million policies were not renewed.

“Climate change is no longer just an environmental problem,” Senator Sheldon Whitehouse, a Democrat from Rhode Island, who chairs the budget committee, said at a hearing on the matter Wednesday. “It is an economic threat, and it is an affordability issue that we should not ignore.”

For those with insurance, premiums rose 44 percent between 2011 and 2021, and another 11 percent last year, according to another report the congressional Joint Economic Committee released this week. A Democratic analyst on the Joint Economic Committee, or JEC, who requested anonymity to comment publicly, said: “The model of insurance as it stands right now isn’t working.”

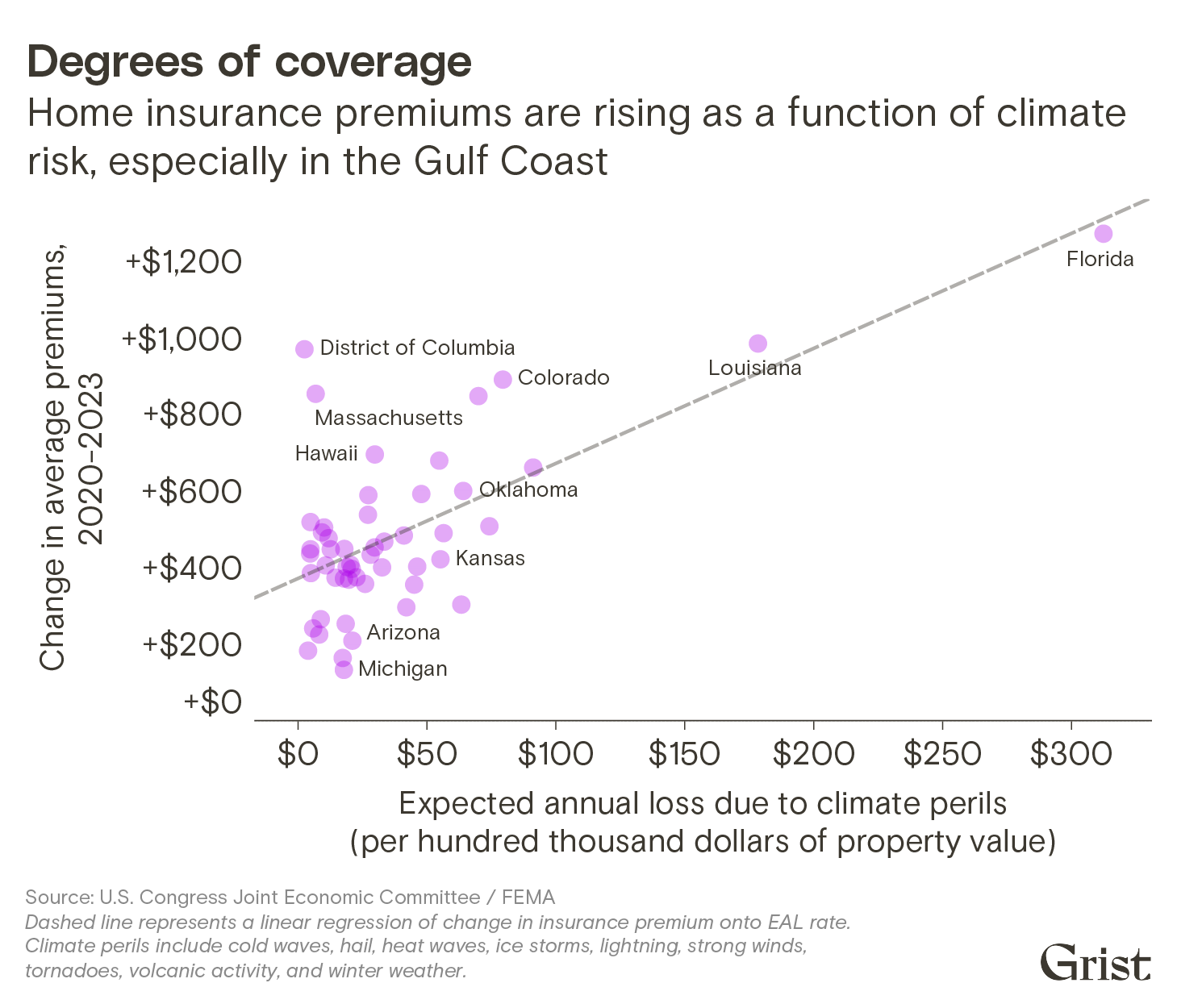

The JEC report included a state-by-state breakdown of premium increases and risk ranking based on climate perils. Florida topped the list on both fronts, and saw a whopping $1,272 climb in annual premiums between 2020 and 2023. Michigan saw the smallest increase at $136. No state saw a decrease over that time.

“This isn’t a red or blue state issue,” said the analyst. “It’s widely applicable across the nation.”

Florida also topped the list when it comes to the number of nonrenewals, according to the Senate committee report that examined state- and county-level data. The rate nearly tripled between 2018 and 2023. Nationwide, in 2023, 48 of the top 50 counties — and 82 of the top 100 counties — with the highest rates of nonrenewal were either flood-prone, faced elevated wildfire risk, or both.

Climate-exacerbated disasters can batter insurance markets because those events create massive financial liabilities for insurance providers, and the companies, called re-insurers, that underwrite them. “Ultimately, all those groups are raising their prices and it’s the homeowners who have to pay in the end,” said Philip Mulder, an economist and expert on risk and insurance at the Wisconsin School of Business. He was a co-author of the state-level dataset that helped underpin the JEC’s work.

Not everyone at the Senate hearing agreed on the role climate change plays in insurance markets.

“The insurance industry is not in the midst of a climate-driven crisis, nor is it about to fall,” Robert Hartwig, an economist and associate professor at the University of South Carolina, told lawmakers. “Climate risk is an important determinant in the cost of insurance, but there has been a tendency, however, to over-attribute the impact of climate change when describing the state of insurance markets.”

What is clear is that costly natural disasters are becoming more frequent, with the average time between billion-dollar events dropping from four months in 1980 to approximately three weeks today. As those risks grow, some insurers are pulling out of states entirely. For example, State Farm and Allstate have left California, and dozens of smaller companies have collapsed or fled Florida and Louisiana.

When that happens, homeowners must turn to government-backed insurers of last resort, which are available in just 26 states and typically cost more than private coverage. Enrollment in those state-run plans has skyrocketed, the JEC report notes, and they now cover more than $1 trillion in assets.

“It all falls on the states,” Rob Moore, director of the Water & Climate Team at the Natural Resources Defense Council, said of the current regulatory setup. “The federal government has very little role to play on the insurance market.”

The JEC report outlines a number of steps Congress could take to give itself a greater role in addressing the problem. For example, it highlights the need for more data collection through initiatives like the Wildfire Insurance Coverage Study Act to better understand the problem. It also points to the proposed Shelter Act, which would provide homeowners with a tax credit covering 25 percent of disaster mitigation improvements that bolster their property’s resilience, reduce the risk of catastrophic damage, and, consequently, lower their premiums.

Moore agreed that adapting old homes, and future-proofing new ones, will be key to righting insurance markets. “The real long-term problem is we’re trying to ensure structures that were never built for the risks and vulnerabilities that they now face,” he said. “If you want an insurable structure 30 years from now, we have to build it today.”

Another shift the report mentions is the possibility of the federal government becoming a re-insurer that backstops climate-stressed insurance markets, something the proposed INSURE Act calls for. France, Japan, and New Zealand have such programs, and the report argues that such a move in the U.S. “could simplify a complicated insurance sector and transfer risks associated with catastrophes to the Federal government.”

For now, though, none of those initiatives have progressed in Congress and all of them are sponsored by Democrats. With Republicans taking control of the House, Senate, and presidency, it remains unclear whether the bills have much of a future.

“That’s a question everyone’s thinking about,” the committee analyst said, noting that taking a dollars-and-cents approach could make the issue resonate across the political spectrum. “Wildfires are raging and we’re seeing more and more flooding. This issue isn’t going away.”