In southeast Costa Rica near the Panamanian border, there’s a group of farmers growing bananas and cocoa without pesticides. Two indigenous groups work communally owned land in the buffer zone surrounding La Amistad National Park. Their cooperative is called the Talamanca Small Farmers Association.

But Talamanca’s growers face the same discouraging problem year after year: They work in a rural area. Some farmers transport their bananas for an hour by boat, and then another three hours by truck, to a processing plant owned by a Chiquita subsidiary. Often, the bananas have to wait for the truck, and they rot. It rains a lot there — the roads frequently flood in the wet season — and sometimes the farmers lose whole truckloads of bananas waiting for the waters to recede. The estimated losses are 40 percent of the crop, said Stephanie Daniels of the Sustainable Food Lab, which has been working with Talamanca to solve the problem of spoilage.

Between 30 and 40 percent of the food grown around the world is lost: spoiled, wasted, or eaten by vermin. Saving even a portion of that could make a huge difference for poor farmers and the environment. Combine a reduction in food waste with increases in farm yields and better livelihoods for the poorest, and we’d have a realistic scenario in which we could improve overall human health and happiness without expanding our agricultural footprint.

As the example of Talamanca illustrates, solving the waste problem can make more food available to eaters while enriching the farmers. (Feeding the world is really a problem of enriching the poor, as I’ve written about here. If you want to catch up on the theory and background, here’s the full series.)

The banana fields of Talamanca.Stephanie Daniels

As Daniels explained it, solving the waste problem is an important step forward to the larger goal of plugging small farmers into the world market. There are people all around the world who want what these Costa Rican farmers grow and are willing to pay a premium for it. Stonyfield Farms buys their bananas to mix with yogurt. People in Switzerland eat their unusual fruits. Basically, there’s a lot of wealth that wants to go to rural Costa Rica in exchange for the stuff that’s already growing there — but instead, a lot of that stuff is rotting on the ground.

And so Talamanca is working on a solution. With money from the government, from Stonyfield, and from the Danone Ecosystem Fund, it’s investigating building a small-scale processor: A machine to peel the bananas, squish them, and aseptically seal them into shelf-stable bags. Today, the farmers depend on Chiquita’s machinery; if they had the food processing technology, they would make a lot more money — and have a lot more control over their destiny.

Around the world

The farmers of Costa Rica aren’t alone. This year the Rockefeller Foundation and the Global Knowledge Initiative produced an in-depth report on food waste in Africa, which showcased dozens of Talamanca-like stories. When farmers simply have airtight bags for their beans, cowpeas, and corn, the lack of oxygen kills insects inside, resulting in millions of dollars in savings. Farmers are using cassava graters and solar driers to process crops that rot easily. They are tapping into the world market with cellphones.

This is a systems-based report, looking at the entire network of farmers, buyers, agricultural educators, and technological capacity. As I read it, it became clear that reducing food waste is not necessarily an end unto itself, but something that comes naturally if you are trying to help poor farmers sell their food and earn a living wage.

North America

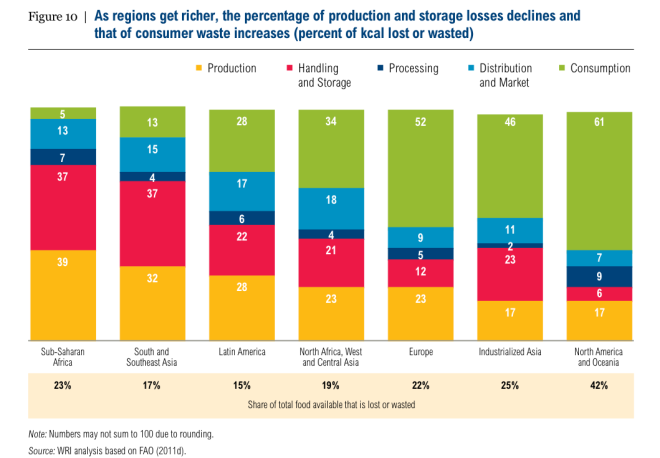

Food waste, however, looks very different depending where on Earth you stand. In poorer countries, the bulk of food waste is due to lack of technology and the inability of farmers to sell their goods. In the richer countries, food waste is all about culture.

“It truly is wasted in this country,” said Dana Gunders of the NRDC, the author of this landmark report. “If we took someone out of Cambodia — or their consumer expectations for food — and combined that with the U.S. technology for preserving food, realistically we could cut a lot of our food waste.”

People often come to Gunders to ask if they should go ahead and eat moldy bread. But she said that sort of thing is a tiny part of the problem.

“It is about eating carrot tops, in a way — but it’s really about having 4,000 sandwiches left over at a conference. It’s about plowing under an entire field because the market shifted.” And it’s about throwing away tons of produce because it doesn’t fit the exacting standards of size and aesthetics that we’ve come to expect and enshrined in our regulations.

Cutting post-harvest waste can be a huge boon to small farmers. But in this country, where a large share of the waste occurs at the consumer level, the impact is a little less clear. Perhaps having more food around would mean fewer farms; that could be good for the environment or bad, depending on what replaced them.

But Gunders thinks that food waste won’t decrease so fast that it dramatically outstrips the rising demand. If we are able to cut waste in this country, that would probably mean that more food produced in the U.S. might be exported as animal feed, as rising affluence increases the demand for meat. Or the land might increase biofuel production. Neither of these outcomes gets environmentalists too excited, but both would reduce the pressure to expand farmland in more sensitive areas.

The takeaway

If we continue business as usual, we’re going to need a lot more food by 2050. This is what food futurists have been calling “the food gap.” The World Resources Institute has suggested that a reasonable goal might be cutting our current food waste in half. Just doing that would take care of a fifth of the food gap.

When we talk about food waste in richer countries, we are mostly talking about consumer waste — reducing that is important for cutting the food gap. But when we talk about food waste in poorer countries we are talking about losses (the yellow and red bars on the graph above) that take money out of farmers’ pockets. And there, the potential in reducing waste is even greater: By enriching small farmers, it would reduce poverty — which is the ultimate goal, and the root cause of hunger.