The panic button hanging around Marcos’ neck evokes the death threat that pulled him out of the Mexican mountain forests of the Sierra de Manantlán and dragged him to the outskirts of Guadalajara. After years of intimidation, he fled his hometown after the body of his 17-year-old son was found lying on the side of a road. The boy was killed, the lawyers on the case say, because, like his father, he opposed the activities of the Peña Colorada mine, which since 1975 has been squeezing the Sierra in search of iron. Over the decades, the iron mine, Mexico’s largest, has depleted the region’s water reserves, deforested its hills, polluted its air, and created divisions in the community.

At the end of each day, after wandering a city with walls, monuments, and kiosks covered with the faces of missing people, Marcos, who is part of the Indigenous Nahua peoples, takes off his panic button, a direct line to the local police. He rarely sleeps. “My head pounds,” Marcos, whose real name Grist has decided to withhold due to recent death threats against him, said. He thinks of his wife, still at their farm in Ayotitlán, of the fallen fences, of the corn that nobody takes to town, of the coffee beans that rot because there is no one to pluck them, of his remaining children, of the cars that menacingly circle their house. The memory evoked by the device on his bedside table cannot be removed. It is a noose around the neck of a man who feels he’s been sentenced.

More than 13 defenders — mostly Indigenous — of the Sierra de Manantlán have been murdered since 1986, according to the nonprofit organization Tskini, which works with Marcos’ community to defend their lands and people. For centuries, the region’s residents have been massacred and disappeared for demanding their right to inhabit their ancestral lands. In recent decades, this task has gotten harder, as extractive industries plundered the mountains.

According to a report released this month from the watchdog group Global Witness, more than two-thirds of the 18 activists killed in Mexico last year were Indigenous, opposed to mining operations along the Jalisco-Colima-Michoacán Pacific coast, where the Sierra de Manantlán is located. The report named Latin America the deadliest region for environmental activists, accounting for 85 percent of the 196 land defenders murdered globally in 2023.

But while public discourse and policy have focused on addressing the most egregious cases of violence against environmental activists — such as assassinations, threats, or forced disappearances — little to no attention has been paid to the invisible traumas and mental health impacts experienced by those who defend the lives of rivers, mountains, ecosystems, animals, and the communities that live within their bounds.

“Around the world, those who oppose the abuse of their homes and lands are met with violence and intimidation,” the Global Witness report reads. “Yet, the full scope of these attacks remains hidden.”

Latin America’s environmental activists live amid a constant threat of violence that permeates their days and bodies and that, like polluted air, tears their insides apart.

Leaders experience insomnia, anxiety, paranoia, panic attacks, depression, isolation, and suicidal ideation, said Mary Menton, an assistant professor at Heriot-Watt University who works with environmental leaders in Brazil. “Some are unable to speak for days at the peak of a panic attack,” she added. A global study of 110 human rights workers, many of whom simultaneously identify as or work with land defenders, found they suffer from post-traumatic stress disorder, demotivation, conflicts with peers, family problems, alcoholism and drug abuse, and somatization, or the physical expression of psychiatric problems. An earlier online survey found that close to 20 percent of human rights defenders met all the criteria for post-traumatic stress disorder and that nearly 15 percent had symptoms of depression.

In some of the Latin American countries where attacks against environmental defenders are particularly high — Mexico, Brazil, Colombia, and Honduras — governments have created protection mechanisms, providing bodyguards, satellite cell phones, and bulletproof vests, among other methods, to guarantee activists’ physical safety. Support for mental health in these systems, however, is close to nonexistent, said Lourdes Castro, coordinator of the Somos Defensores program, which monitors violence against human rights defenders in Colombia. Instead, psychological care falls to private or nonprofit organizations, which don’t have the resources to meet the growing need — in the rare cases when land defenders are open to, and trusting of, that kind of care. “We talk about the problem, the solution, the hearings, that there is going to be a meeting, but rarely about this,” Marcos said.

“Most [activists] don’t have the money to pay for it. And even if they did and had access to somebody,” said Menton, “then there’s also the resistance to it. Some people, for understandable reasons … they don’t trust very easily.” Added to this are the challenges of getting in and out of their territories — usually located in remote areas — or the unstable connection to the internet and telephone signal for virtual care.

As a response, psychologists, social workers, and lawyers have been building a network of safe houses and temporary shelters throughout Latin America that support the mental health of social leaders and human rights defenders and, increasingly, threatened environmental leaders. These shelters have become one of the few safe spaces to deal with individual and collective grievances, Menton said. Beyond addressing an individual’s mental state, the therapy in these spaces aims to address collective trauma, said Clemencia Correa, a Colombian psychologist exiled in Mexico since 2002 because of her work with civil war victims.

While the need to keep the locations of these places secret makes it impossible to have clear figures regarding their existence, there are at least 10 shelters in Central and South America that make up this growing regional support network. Through theater, art, and handicraft workshops, among other methods, their psychosocial approach is expanding beyond the shelter walls and slowly permeating the work of environmental organizations as well.

“It’s normalized to live under constant stress with mental health issues,” said Adriana Sugey Cadena Salmerón, a lawyer working with Marcos. In 2020, she and her colleague Eduardo Mosqueda founded Tskini, the organization that works with leaders of the town of Ayotitlán and places psychological health as a core priority. “If we start to pay attention, to care for each other, then I think we’ll be stronger,” she said.

Starting in the 1940s, Marcos’ community, the Nahua, watched as logging companies, supported by local and national governments, shaved the mountainous forests and grasslands of their ancestral Sierra de Manantlán. The region’s name comes from the Nahuatl word “amanalli,” which means “place of springs or weeping waters,” and it provides drinking supplies to almost half a million people across western Mexico.

Marcos’ father-in-law and Nahua leader spent decades defending the Sierra de Manantlán and advocating for the recognition of Indigenous lands. He was sent to jail in 1993 after leading one of those protests. Marcos helped organize a rally to demand his immediate release in Telcruz, in the Mexican state of Jalisco. Police broke up the demonstration with gunfire. Two of those bullets found a place to bury themselves: the bodies of Juan Monroy Elías and José Luis, Marcos’ younger brother. He was just 22 years old.

In parallel to this struggle for land recognition, and after decades of pressure from environmental organizations and Indigenous leaders, the loggers eventually left in 1987, when most of the Sierra was declared a protected area. But one major extractive industry remained: the Consorcio Minero Benito Juárez-Peña Colorada iron mine, opened in 1975. The open pit mine, which spans over 96,000 acres, including nearly 3,000 of Nahua collectively owned lands, disfigured the landscape, replacing green mountains with mounds of crumbled stone. According to company numbers, the mine produces 3.6 million tons of iron pellets every year, and 4.1 million tons of iron concentrate, providing 30 percent of Mexico’s industry’s needs. Steel giants ArcelorMittal and Ternium — which own and operate the mine — didn’t respond to multiple requests for comment.

Murders, Menton said, are just one of the violent actions environmental leaders face around the globe. Several organizations report that leaders are increasingly facing threats, intimidation, judicial persecution, smear campaigns, repression, and daily microaggressions. In fact, Global Witness found that criminalization is now the most used tactic to silence environmental defenders. Marcos has been detained three times, the longest one lasting six days, during which he was beaten by police in Guadalajara, he said.

The intersection of all these forms of violence — that happen across time, space, and even generations — creates a feeling of permanent aggression, Menton wrote in 2021. “Living under this constant threat creates what we have called atmospheres of violence or climates of horror,” a slow violence that often goes unnoticed.

From the 1990s onwards, at least eight people throughout the Sierra were killed for their activism. Despite the creation of an ejido — legally recognized and collectively owned lands — in 1963, outsiders have infiltrated decision-making positions that govern the territory. After a controversial election process in 2005, Jesús Michel Prudencio, a Peña Colorada employee, became the ejido’s legal representative, known as the ejidal commissariat, and authorized the expansion of the mine. Subsequently, leaders from the community have been pressured to drop their campaigns against company-friendly candidates, sometimes being murdered for not doing so. Paramilitaries soon began to prowl the Sierra openly, and the criminal syndicate Jalisco New Generation Cartel began opening illegal mines on top of its drug trafficking activities.

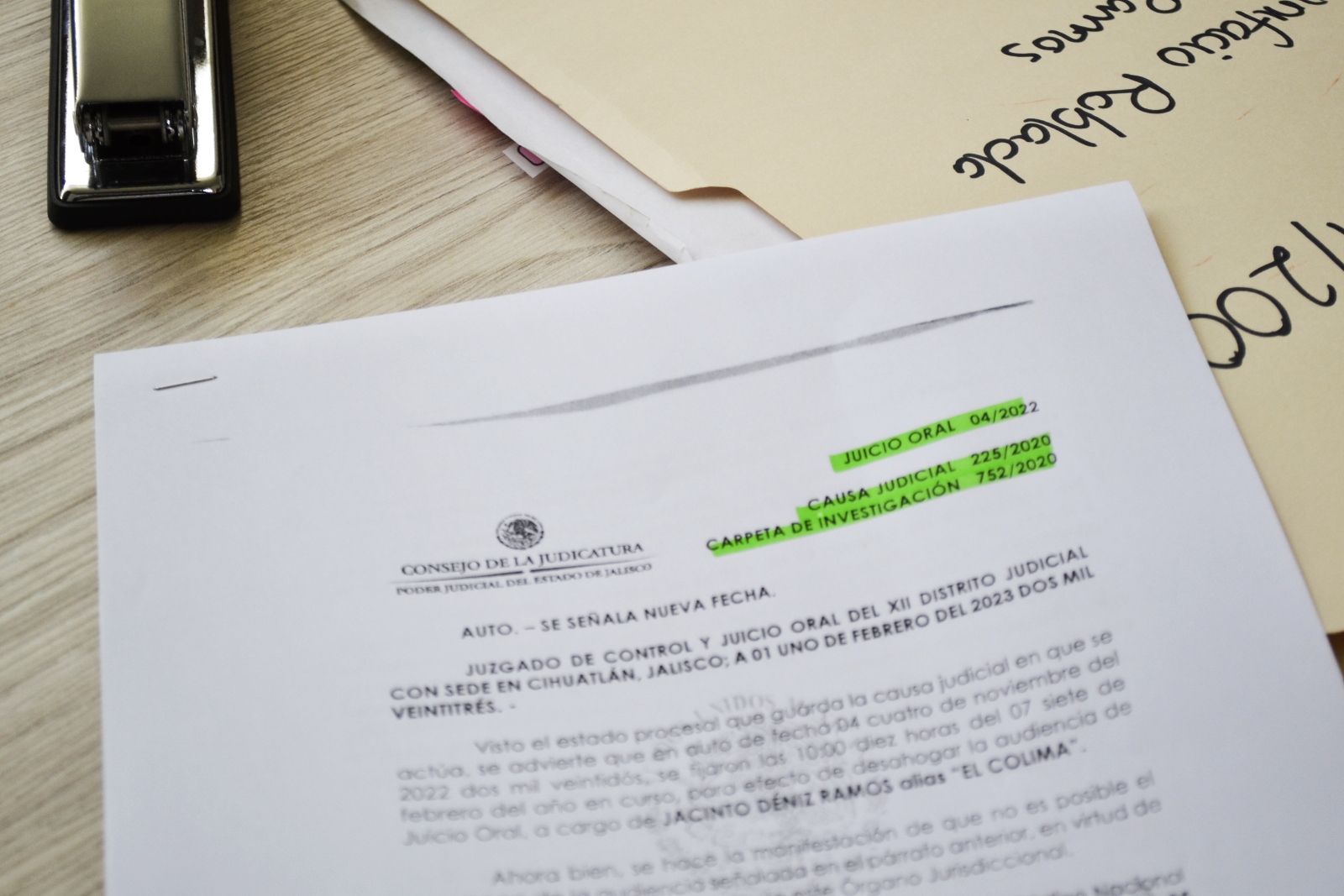

For 23 years, Marcos juggled his work as a school teacher with advocacy, sometimes teaching the kids of those in the community working for the Jalisco New Generation Cartel. He led protests demanding payment from the mine for their use of community lands, pleaded with government officials for justice and collective protection, and was the face of lawsuits denouncing outside interference in the governing of Nahua lands. But that balancing act ended on the morning of October 26, 2020, after his eldest, then 17, dropped him off at school. Hours later, Marcos saw his body lying on the side of the road in the community of Rosita. The high school boy had begun to speak up on social media about the shady dealings of the ejidal commissariat. “I made the mistake of talking about the abuses, which obviously bothered him,” Marcos said. A year later, he left Ayotitlán. He arrived in Guadalajara, Mosqueda, his lawyer, said, “like a scared little mouse.”

“I almost lost my mind,” Marcos recalled. He couldn’t sleep. When he slept, he had nightmares. And he feared — and still fears — persecution against him. “I had to talk to priests, psychologists, [it was] hard. I am getting over it, but very little … I walk around all day with problems, the feeling that something will happen.”

Two more land defenders have been killed in the Sierra de Mantatlán since 2020. One of them was part of the National Mechanism for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists program, which provided physical security measures. The other murder hasn’t been prosecuted. In 2023, Marcos received new threats, and a pick-up van parked outside his home for four hours.

Marcos receives counseling from a psychologist paid for by Tskini, as well as takes medication. He is also in graduate school, studying for his master’s in educational pedagogy. He sees his wife and children every two or three months, when his wallet and safety conditions allow. “Police visit during the day, but at night they leave, and the criminals are still free,” he said. The Jalisco prosecutors’ office investigating his son’s murder declined to comment on an active investigation.

Despite its limited resources, Tskini works with a mental health professional who cares for Marcos, the organization’s two lawyers, who also face threats through their work with leaders from Ayotitlán, and a second leader who also had to leave his home and settle in Guadalajara. Without the organization’s support, Marcos could not pay the taxi and bus fare to the appointment, or buy the medications prescribed by the specialist.

Marcos said defenders used to organize to demand the release of their leaders, or they would go as far as Mexico City or Guadalajara to expose abuses. Not anymore. Today, no one wants to sign the police report requesting an investigation into the death of José Isaac Santos Chávez, his colleague assassinated in 2021. No one wants to associate their name with the struggle for the Sierra. “They are afraid,” he said. “They know they’ll be harassed or forced to disappear.”

In Purépecha language, from the central Mexican state of Michoacan, Tskini means “from where something sprouts,” Cadena Salmerón said. In a climate of horror, she said, “we have to be well, we have to be focused, we have to have peace of mind.”

In a humble neighborhood south of Bogotá, Colombia, there is a house so unremarkable that it is easy to walk past. Except for the cat that wanders the nearby rooftops, its residents rarely go out and never after 8 pm. They are discreet, almost as nondescript as the building itself.

There is fierce persecution against those who live there — threatened social and environmental leaders. Military helicopters have overflown previous versions, looking for its inhabitants. Unknown men have entrenched themselves outside. That’s why, every now and then, the residents move and occupy another unassuming building.

Behind the metal door, however, it is anything but bland. In the back, in a colorful mural, a capybara, a jaguar, a snake, and a cup of coffee surround children playing in the sun; two women weave the map of Colombia; flowers, roots, birds, guitars, and flutes sprout from a heart. Photos and posters of assassinated leaders hang on the sky-blue walls of a room that doubles as a music space and library. A faded declaration of human rights hangs on the wall leading to a huge hall in the back.

A mural painted by human rights and environmental activists and their children in the Corporación Claretiana safe house south of Bogotá. María Paula Rubiano A.

Music room and gathering spaces in the Corporación Claretiana safe house south of Bogotá, designed to help residents tackle mental health issues that arise from their activism. Gustavo Torrijos / El Espectador & María Paula Rubiano A.

Inside, the residents — who usually stay for up to three months — sleep in bunk beds, cook and clean for each other, and spend their hours resting, reading, and talking to each other and the therapists in the organization. Some days, they go to the sewing room and work through their traumas by using their hands. Not all days are good: Sometimes someone wakes up screaming at dawn with a panic attack, in which case one of the psychologists rushes to the house to help them through it.

“We’ve seen many generations grow,” said Jaime Absalón León Sepúlveda, founder and director of the Corporación Claretiana Norman Pérez Bello, which runs the home and has been sheltering human rights defenders from all over Colombia since 2003. “At first it was about saving people from being killed and having a safe place where they could breathe, be with their family and begin to grieve.” But he soon realized they needed “therapeutic spaces, collective and individual, to deal with the crises.”

The work in the house south of Bogotá is based, above all, on a branch of psychology born between the bullets of the Central American civil wars in the ’70s and ’80s. Called liberation psychology or psychosocial therapy, it is a therapeutic alternative to traditional clinical work, focusing on conversations and tools like theater, painting, writing, and other artistic endeavors that allow patients to put their individual suffering within a political context. The method later spread throughout Latin America, serving victims of Colombia’s armed conflict; young people in the Brazilian favelas, or informal settlements; relatives of the disappeared; and torture survivors of the Chilean and Argentinian dictatorships.

Soon, centers focused on the mental health of human rights activists and land defenders started cropping up. In 2013, Correa, the Colombian psychologist, founded Aluna, an organization focused on this type of therapy in Mexico, where she’s been living in exile since 2002.

Correa left Colombia after helping to uncover a military intervention, known as “ Operation Genesis,” that had been planned by paramilitaries and the Colombian army to access the fertile lands — perfect for agribusiness — and forests in the Colombian Caribbean, an area known as Urabá and close to the Darien Gap. At first, she recalls, no one was able to tell them what had happened. “People said, ‘We don’t know, the bad guys kicked us out,’” Correa says. “They couldn’t name it.”

Everyone’s sense of identity was shattered, separated from the land they had long called home. Little by little, information started to trickle in: Bodies began appearing on the streets of Turbo, located before the start of the Darien Gap. At least two local officials disappeared. Days before the displacement in 1997, army helicopters dropped bombs over the area. “The monsters are here,” the children had said. The military came to some villages to tell them that if they didn’t leave in three days, they were going to kill them all. Then the paramilitaries came in. They burned down the houses. They dismembered the body of Afro-Colombian leader Marino López Mena in his small village on the banks of the Cacarica River.

“When we retraced these events with people, it was very painful. But being able to name it allowed us to try to understand so that this would not be totally hushed up,” explained Correa. Correa and her colleagues connected the operation to logging interests over the fertile lands of the Urabá region — a fact recognized a decade later by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights and, more recently, by Colombia’s Truth Commission. With the allegations came threats to Correa and others. And then, exile.

When she landed in Mexico, Correa immediately contacted environmental and social organizations. She learned that although the country had not suffered decades of bloody civil war like Colombia, since the late 1950s, when guerrilla groups started to appear across the country, the government had waged a low-intensity war that, with the excuse of stopping rebel organizations, attacked government opponents, leftist leaders, students, and rural and Indigenous people. Correa saw how this “dirty war” was based on the same terror tactics used in Colombia: arbitrary detentions, torture, selective assassinations, massacres, and forced disappearances. And, like in Colombia, victims felt guilty, oscillating between apathy and paranoia. Some did not sleep, others lived in fear. A few drank excessively. All were terrified.

Traditional psychology, developed through carefully manufactured and controlled experiments on college campuses in the United States, did not conceive the depth of these victims’ and activists’ wounds, Correa said. Nor did it know how to heal them. “We rely on communities’ capacities to build resilience, which more than resilience is resistance to keep on living,” León Sepúlveda explained about this line of work.

Correa’s organization, Aluna, instead applies an approach to victim support proposed by Ignacio Martín-Baró in the 1970s. The Spanish psychologist and priest, who graduated from Chicago University, devoted his life to unraveling the impacts of political violence in El Salvador, where a string of military governments and conservative presidents violently repressed any protest against social and economic inequality. Above all, Martín-Baró wanted to find ways to rebuild communities. His “liberation psychology,” as it’s known, states that if the causes of a wound are from an oppressive political and social context, to heal, people and communities should first understand that context and its key players. Then, after facing the impacts of that violence with psychosocial support, victims may shed their trauma and reaffirm themselves as political actors.

This new way of understanding their reality allows them to rebuild themselves personally and collectively, “enabling them not only to discover the roots of what they are, but also the horizon of what they can become,” Martín-Baró wrote in 1985. Under this method, healing is understood as a political act of freedom. Four years later, in 1989, Martín-Baró was assassinated by the Salvadoran army at the Central American University, where he was the head of the psychology department.

After the priest’s assassination, his thinking spread across Latin America. In 1998, the first International Congress of Liberation Psychology was held in Mexico City, then held annually until 2005 (since 2008, it was held every two years until 2016). Professionals from all over the region gathered to exchange ideas, experiences, and techniques. In 2008, Correa joined the gathering to talk about counseling victims of sexual torture. Around that time, León Sepúlveda had opened the doors of the first safe house of the Norman Pérez Bello Corporation, furnished with a couple of armchairs and beds donated by the Roman Catholic Claretian order, which he had abandoned. The earliest residents were victims of Colombia’s internal conflict, but throughout the years, it has hosted LGBTQ+ rights activists, youth advocates protesting the lack of opportunities in cities, victims of state violence and, more recently, environmental defenders.

In practice, psychosocial counseling takes many forms, said Ajax Sanhueza, director of Colectivo Casa, a human and environmental rights advocacy group working with Indigenous leaders in Bolivia since 2008. They worked with women from the Red Nacional de Mujeres en Defensa de la Madre Tierra, or the National Network of Women in Defense of Mother Earth, who decided they wanted to create short videos in which handmade dolls dressed as Bolivian cholas, representative of the threatened Indigenous leaders that voice them, denounce how mining activities threaten the water supplies of many Indigenous tribes, as well as calling for women’s self-care.

People must understand what has happened to them, on individual, collective, and historical levels, Correa explained. Suppose people don’t understand, for example, that their territory is an attractive place for certain industries or illegal economies. In that case, it is difficult for them to make sense of the terror they experience and take the appropriate steps to protect themselves, she noted.

It’s hard to tell how many organizations have used or currently use this type of therapy in Latin America. Mark Burton, a social psychologist who has studied this trend since its inception, wrote in 2004 that practicing psychologists do not systematize their experiences. Correa said that the lack of academic production is due, in part, to the fact that Latin American universities have not been interested in the practice for more than a decade. Diploma courses and lectures on the subject, such as the Martín-Baró International Seminar at the Javeriana University in Colombia or the diploma course for forcefully disappeared missing persons at the Autonomous Metropolitan University, Cuajimalpa, do not permeate the curriculum of psychology faculties, she said. “There’s a lot of prejudice against talking about a political approach, as though it would take away from the rigor of psychology,” she explained. Correa noted that such a position negates the fact that traditional psychology already carries ideological baggage. “One of Martín-Baró’s missions is the liberation of psychology itself.”

But networks do exist. As violence against environmental leaders in Brazil escalates, “this issue of mental health support and psychotherapy kept coming up again and again and again,” Menton said. Existing protocols are insufficient. “If you’re in the middle of a crisis, the last place you want to be is in a cold hotel room in a city where you don’t know anyone, and you don’t have a support network,” she said. “We were wondering, how do we create spaces to heal? This is all growing under the surface, and the idea of a house was there, like a dream.”

In 2018, after years of ruminating, Menton led the purchase of a property in the Brazilian Amazon with the organization Not1More and the Zé Claudio and Maria Institute. Aluna contributed its expertise by training volunteers in Brazil on psychosocial principles. Casa La Serena, a shelter located in Mexico City, has helped Menton and her colleagues imagine what amenities the house should have so that its inhabitants “feel safe,” she said, “feel that this is a place to breathe, sleep and rest.” So far, at least four adults have stayed in Casa de Respiro, and dozens have participated in workshops on self-care and holistic strategies for dealing with trauma, Menton added.

At the Corporación Claretiana house south of Bogotá, a sewing workshop has been the main vehicle for providing support, León Sepúlveda said. Residents gather in a small space next to the large mural room every Saturday to talk and sew. “The names [of the activities] here are all about reactivating the possibilities of life. [That space is called] ‘Mending our history, weaving hope,’” León Sepúlveda said. “People talk, there is a catharsis there.”

In 2023, after 20 years in exile, Correa was reunited in Bogotá with León Sepúlveda, whom she had first met when he was young student priest who often gave refuge to rural farmers, Indigenous peoples, and Afro-Colombians fleeing war. Convened by the international organization Bread for the World, about 10 mental health shelters located in Colombia, Mexico, Brazil, Costa Rica, Honduras, and Guatemala are part of an effort, still in its infancy, to relocate the most at-risk leaders throughout the region. Also, Correa said, they are looking to create safe havens in rural areas, as one of the biggest challenges for leaders is adapting to a city lifestyle.

Caring for those who care for their communities and territories is a risky and sometimes traumatic job. León Sepúlveda has been threatened several times, and some of his closest collaborators have been killed. To cope with the burden, the defender plays Andean music with his children and friends, works in the fields, and writes poetry. Like the house’s inhabitants south of Bogotá, he cannot imagine abandoning his mission.