How do you put a year like 2021 into words?

It began in turmoil, with a mob invading the Capitol then President Joe Biden’s inauguration two weeks later (remember Bernie Sanders’ cozy mittens?). The pandemic stuck around, prompting seasonal mood swings and a greater familiarity with the Greek alphabet. People showed off their Band-Aids in vaccine selfies in the spring, and fretted over the spread of Delta in the summer and then Omicron in the fall.

And it was another year marked by fires in the West and flooding in the East, with a record-shattering “heat dome” that turned the normally temperate Pacific Northwest into a 120-degree oven in late June.

Dictionary editors try to make sense of the chaos the way that language nerds typically do: by analyzing it one word at a time. With the final flip of the calendar, they start picking their “words of the year” to capture its spirit. The words aren’t necessarily new terms, but ones that became more popular or sent people racing to Google. Merriam-Webster went for the obvious and chose vaccine; Oxford Languages picked the shortened form vax. Collins Dictionary, based in Scotland, settled on NFT, an abbreviation for non-fungible token, a kind of digital collector’s item. Cambridge Dictionary went all motivational-poster and selected perseverance to salute all those who stuck it out through a seemingly endless pandemic and to commemorate the NASA rover that landed on Mars in February.

The warming planet led to other shifts in our vocabulary. Scientists found novel ways to ring the alarm bells that have been going off for decades, and activists coined new phrases to express their exasperation. Mother Nature’s wrath crystallized into terrifying expressions: glacier blood, hawkpocalypse, weather whiplash.

The year also ushered in expectations that the federal government would take sweeping action on climate change, with a political party that acknowledges the science in control of both houses of Congress and the White House. But just as visions of a blissfully “normal” post-vaccine summer were crushed by the Delta variant, those hopes met the slow-grinding political machine, and Democrats’ razor-thin majority shrank ambitions.

Grist’s picks for the words of the year reflect the zeitgeist of the climate movement as well as the realities of life on an overheating planet. They capture activists’ anger (blah, blah, blah), the jargon (climate-positive) and the signs of progress (green vortex) that characterized 2021.

Blah, blah, blah

An accusation of empty, meaningless words.

In January, at a gathering of world leaders in Davos, Switzerland, Swedish activist Greta Thunberg stressed the urgency of cutting emissions, criticizing corporations and countries for promises with “vague, hypothetical” targets such as going net-zero by 2050. “We understand that the world is a complex place and that change doesn’t happen overnight,” Thunberg said. “But you now have had more than three decades of blah, blah, blah. How many more do you need?” The phrase became a refrain in her speeches surrounding COP26, the international climate conference in Glasgow, with searches for blah, blah, blah jumping during the first week of November as the conference ramped up. The phrase adorned protest signs in Italy, Portugal, and France, reflecting a widespread attitude that the future is at stake and that the people in charge aren’t acting like it.

Civilian Climate Corps

A government jobs program to take on climate change and prepare for its effects.

Less than two weeks after taking office in January, Biden signed an executive order to create the Civilian Climate Corps, sort of like an AmeriCorps for the planet. It hearkens back to one of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s signature New Deal programs launched during the Great Depression, the Civilian Conservation Corps, which put 3 million people to work making hiking trails and fighting fires, among other duties. Biden has promised to give those who sign up jobs planting trees, restoring public lands and waters, and improving access to parks. But the program still needs funding. Biden’s Build Back Better package, which set aside $30 billion for the new CCC, passed the House in November but was recently shelved in the Senate.

Climate-positive

Removing more carbon from the atmosphere than you put in. A synonym for carbon-negative.

Sure, it might sound like you’ve just tested positive for some new disease associated with our warming planet, but being climate-positive is actually considered a good thing in the world of corporate pledges. As if expressions like carbon-neutral and net-zero weren’t already confusing enough, more and more companies, like IKEA and the TurboTax creator Intuit, are now aiming to go climate-positive — essentially, going a step beyond zeroing out emissions. In use for at least a decade or so, the phrase saw a spike in Google searches in October when Panera, the fast-casual soup and bread chain, declared its climate-positive intentions, as did the race car team Williams F1. More CEOs could soon steer their companies in the same direction if they take advice from a new book, Climate Positive Business: How You and Your Company Hit Bold Climate Goals and Go Net Zero.

Climate reparations

When countries that historically caused the most damage from climate change pay the ones that are dealing with its worst consequences.

Rich countries are behind on the $100 billion they promised to give poor countries every year to help them switch to clean energy and deal with rising seas, searing heat, and deadly downpours. At COP26 in Glasgow, campaigners around the world called delegates from wealthy countries to follow through on these promises and increase compensation goals to more than $1 trillion per year. That didn’t materialize, although developed countries did agree to double the funding for adaptation by 2025. The idea behind climate reparations rests on the belief that countries that have emitted the most greenhouse gases have a moral responsibility to own up and pay up. To name names, the world’s top historical polluter is the United States by far, followed by China and Russia.

Code red

A warning of imminent danger.

In August, not long after a searing heat wave scorched the Pacific Northwest, snapping record temperatures for three straight days and killing hundreds, the U.N.’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change released a landmark report warning of “irreversible” planetary tipping points. In a statement, U.N. Secretary-General António Guterres reached for language associated with hospital emergencies, saying that the findings amounted to “a code red for humanity.” People must have been frightened, or at least intrigued, judging by the spike in Google searches for it. Many summaries of the U.N. report used the dramatic expression, and it continued to pop up in headlines months later.

Doomsplaining

When someone “helpfully” explains that the world is headed toward inevitable collapse.

Last year brought us doomer, a person convinced the climate apocalypse is coming; this year gave us doomsplaining. The word, a relative of mansplaining, was coined in September by Richard Waite, a researcher at the World Resources Institute. In a much-liked tweet, he observed that doomers kept popping into discussions about addressing climate change and saying “WELL ACTUALLY naive one it’s too late and we should all just accept the end of civilization as we know it.” Waite countered that “every fraction of a degree matters.” While a relatively small proportion of Americans think it’s too late to do anything about global warming — about 13 percent — social media tends to amplify divisive messages, so people encounter plenty of doomsplaining online.

Glacier blood

Reddish-colored snow.

The glaciers are bleeding, and researchers are worried. This summer, the New York Times noted an increase in pink-hued glaciers around the world. The phenomenon, caused by snow-dwelling algae, can speed up the melting of glaciers since the darker colors absorb more sunlight than a white, reflective surface. In the French Alps, Cara Giaimo wrote, locals call this sang de glacier, or “glacier blood.” Visitors are more likely to call it “watermelon snow,” which frankly sounds delicious.

Green vortex

A feedback loop in which business, technology, and politics conspire to speed up decarbonization.

By most accounts, the U.S. government is not doing so well on climate change. It has failed to pass overarching legislation to cut carbon emissions, and the previous president attempted to pull out of the international Paris Agreement. But progress is happening. U.S. emissions have dropped more steeply than promised by President Barack Obama’s proposed 2009 climate bill that never passed. Robinson Meyer, a writer at the Atlantic, described the mechanism behind this momentum as the green vortex, an economic spiral in which piecemeal policy incentives and aggressive corporate carbon cuts send the country toward a clean energy future. Some vortex-y events this year: Two big carmakers, GM and Ford, rushed to build electric vehicles while people rushed to buy them, ExxonMobil shareholders voted to put three directors on the oil giant’s board who want more renewables and less fossil fuels, and solar power was declared “the cheapest electricity in history.”

Hawkpocalypse

A massive die-off of young birds of prey.

When searing heat baked the West Coast in June, it cooked millions of clams, mussels, and snails in their shells and sent baby birds plunging to their deaths as they tried to escape the sunbeams beating down on their nests. The coordinator for Shasta Wildlife Rescue and Rehabilitation in Anderson, California, told the Washington Post she saw baby birds “falling out of the sky” and declared it a hawkpocalypse. A center in Portland admitted more than a hundred Cooper’s hawks in four days in June as temperatures crested above 110, almost 10 times the number it would typically see in a full year.

Meatposting

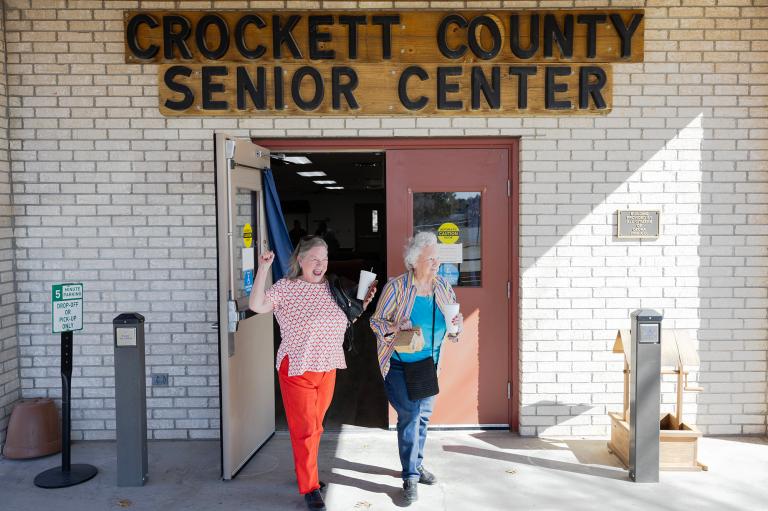

Sharing pictures on social media that glorify meat consumption.

You’ve probably seen a version of it before: a big juicy steak, preserved in a photo; a hot dog eating contest champion posing with a giant medal and a mountain of franks. The caption next to it might chant something like “MEAT! MEAT! MEAT!” Given that beefy livestock account for up to 18 percent of the globe’s greenhouse gas emissions, this kind of meatposting is sure to raise some eyebrows among the climate-conscious. Emily Atkin, a climate writer who coined the term, compared meatposting to “filling up your car’s gas tank and being like ‘hell yeah gas!’” Of course Atkin’s idea met backlash online — including one article titled “The Joy of #Meatposting” — but it also sparked discussion about what meat means to people and why America is so hooked on it.

Megadrought

A period of extreme dryness that can last decades.

The West is in a drought so huge that everyone started throwing the prefix mega- in front of it. Much of the Southwest has been in chronic drought for 20 years, and it’s not just about low rainfall, but also hotter temperatures. A warmer atmosphere sucks more moisture out of the ground, leading to a so-called hot drought. Add megadrought to the growing list of oversized problems: megafires, megastorms, and megafloods.

Weather whiplash

Dramatic swings between extreme conditions.

The changing climate doesn’t just bring bad weather — it can take us for a seesaw ride between different types of bad weather. Take this fall’s weather whiplash in the Pacific Northwest. After a summer of record-smashing heat, parching drought, and roaring wildfires, devastating rains fell on the region from October to December, causing flash floods and mudslides that trapped hundreds of people. Seattle had its wettest fall on record with more than 19 inches of rain. Scientists expect to see even more extremes, and more weather whiplash, in the future.

Previous Words of the Year posts:

2020: Anthropause, ghost flights, spillover: Only a pandemic could bring words like these

2019: Birth strike, flygskam, Pyrocene: And we thought things couldn’t get worse

2018: Firenado, hothouse, smokestorm: The year fires went wild

2017: Hotumn, meatmares, ecoanxiety: Oh, how young we all were then