With so much focus on the 2020 presidential race, it’s easy to forget there’s also a lot at stake elsewhere on the ballot. Seats in the Senate, House, and state legislatures — not to mention quite a few governors’ roles — are just a few of the positions up for grabs on Election Day. That means voters will have an opportunity to shift the balance of power between Republicans and Democrats on both a local and national level.

In some of the nation’s most heated Congressional races, concern over climate change just might be the issue that tips the scales. Worry, after all, is a particularly significant emotion during elections in that it tends to mobilize voters rather than paralyze them, according to Anthony Leiserowitz, director of the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication.

And there’s plenty to worry about, given the current political climate around, well, the climate. The issue — and, frankly, the world — is hotter than in any previous election cycle. After years of record-breaking heat waves, wildfires, and hurricanes, more than 60 percent of Americans now say climate change is affecting their communities. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, 77 percent of young voters — the mobilizing force behind the recent climate protests — ranked environmental protection as their top political issue. And even now that we are grappling with coronavirus, two-thirds of Americans remain worried about climate change.

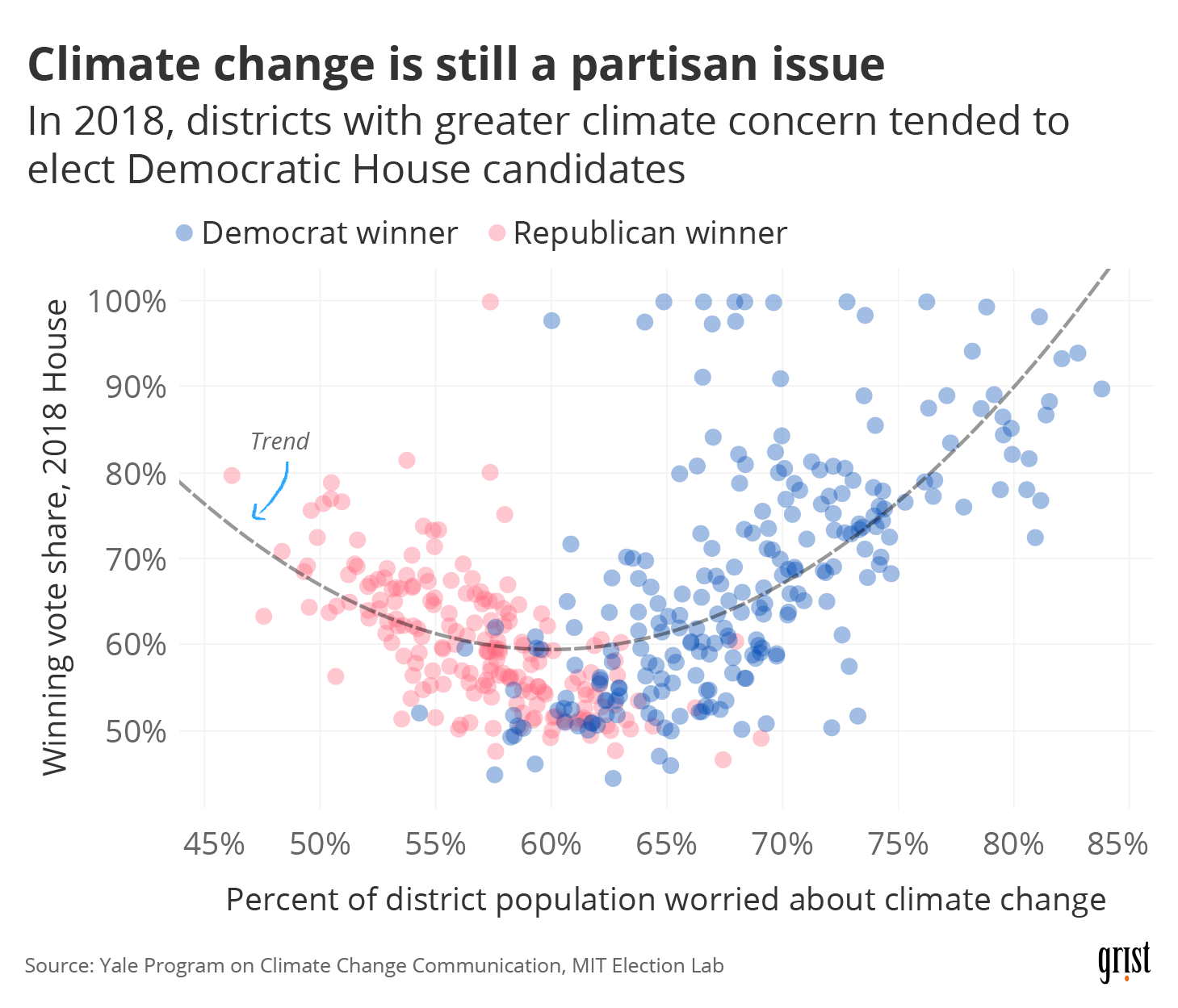

While climate might become more of a bipartisan priority in the near future — voters between the ages of 18 and 38 tend to have similar views on the issue, regardless of party affiliation — environmental concern currently tends to split along party lines. In the 2018 midterms, for example, the districts most worried about climate change voted overwhelmingly for Democratic House candidates, whereas the least-worried ones favored Republicans.

Clayton Aldern / Grist

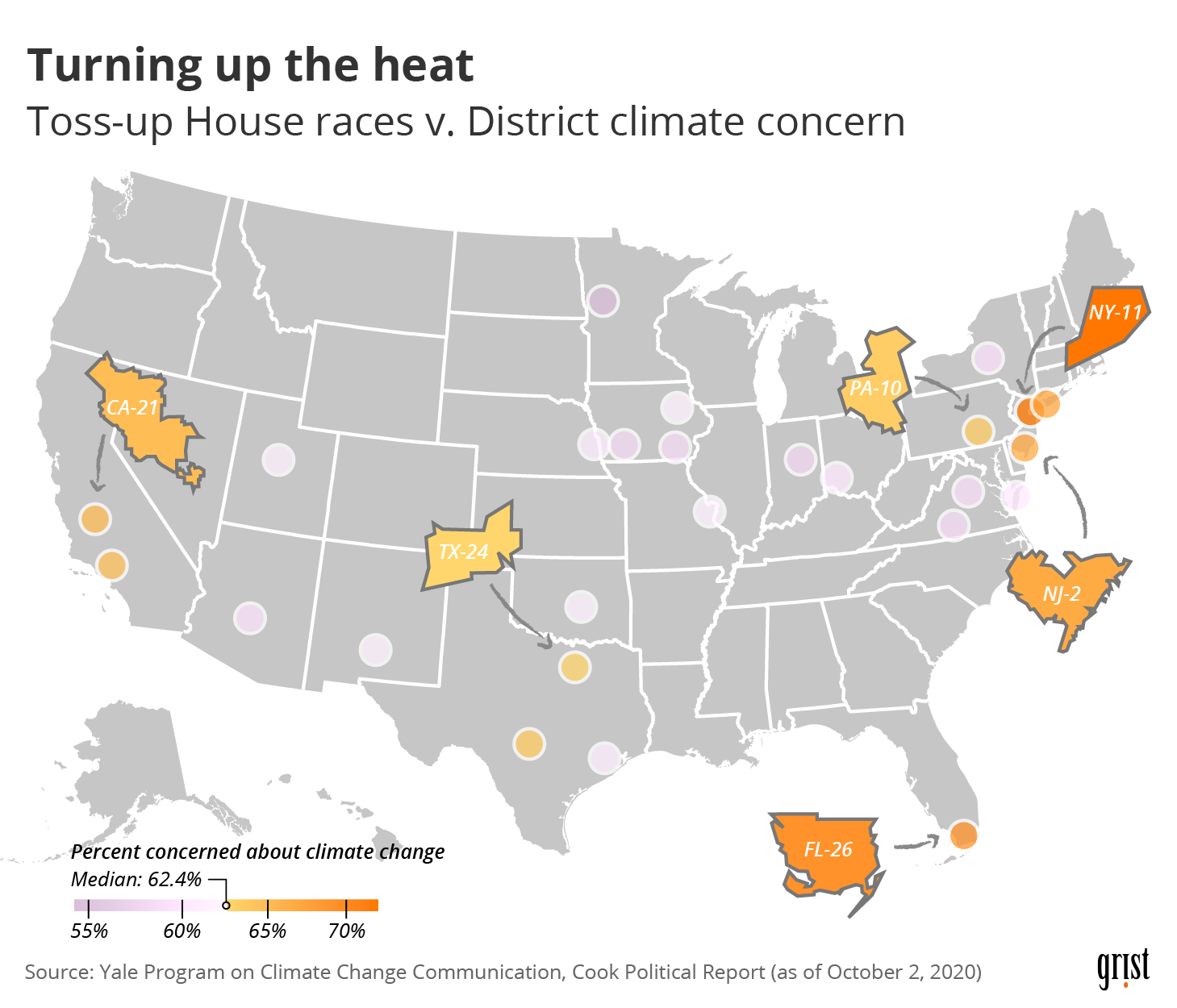

Assuming those trends hold in 2020, we were curious how climate concern would influence the country’s most hotly contested congressional races. Grist once again looked at the Cook Political Report’s assessment of the most competitive House races and combined it with data from Yale’s Program on Climate Change Communication that measures the level of climate concern in each district. Among the 26 races listed as toss-ups as of October 2, 2020, eight have higher levels of climate concern than the national average — where 62 percent of a district’s electorate is worried. (In fact, a majority of voters in all 26 competitive districts said they found the issue concerning.)

Grist decided to take a closer look at six of those races where voters have higher-than-average levels of climate concern — an indication that they might prefer a candidate whose platform includes more aggressive climate action.

Clayton Aldern / Grist

The six Congressional toss-up races are scattered throughout the country, and include both urban and rural pockets. We chose to examine House races where environmental crises had altered the political landscape or candidates had notably different climate views that could divide voters.

New York District 11 – 72 percent worried

It’s not surprising that this coastal New York district is the toss-up race where voters are most worried about climate change — it includes the southern portion of Brooklyn and all of Staten Island, which was completely reshaped by Hurricane Sandy in 2012. Some Staten Island neighborhoods experienced up to 9 feet of storm surge, and the borough accounted for half of New York City’s Hurricane Sandy death toll.

Both candidates vying for the area’s House seat agree on one thing: building a sea wall to protect Staten Island from the next superstorm.

“Residents in my district have lived in fear of devastating flooding; they live in fear of another superstorm,” said incumbent Democrat Rep. Max Rose in his inaugural speech to Congress in January 2019. “The question isn’t whether the storm will hit again, it’s when.”

Soon after being seated, Rose introduced a bill to fast track construction of a seawall along the shoreline of Staten Island. His bill, which was wrapped into the major Natural Resources Management Act, was signed into law in 2019. Rose’s challenger, Republican New York State Assemblymember Nicole Malliotakis pushed to include funding for the project in the state’s 2018 budget. The 5-mile seawall would save the island an estimated $30 billion in damages each year, and reduce flood insurance premiums for residents.

But a seawall alone can’t hold off the community’s climate risks forever, and some parts of Staten Island are already undergoing more drastic climate adaptation measures. New York State has already bought out hundreds of Staten Island properties as part of a managed retreat plan — a process of evacuating and re-greening high-risk neighborhoods. And as the island continues to face rising seas and more frequent storms, this surely won’t be the district’s last climate-focused election.

Florida District 26 – 69 percent worried

Climate denial is not on the ballot in this southern Florida district, which was also on Grist’s list of worry wards in 2018. Both the incumbent, Democrat Debbie Mucarsel-Powell, and her challenger, Republican Carlos Gimenez, recognize the dire impacts that the climate crisis may have for their constituents in Miami-Dade County and the Florida Keys.

Mucarsel-Powell is a vocal climate advocate. She was even a co-sponsor of the Green New Deal resolution — something that may or may not help her in this particular region. After narrowly defeating climate-conscious Republican Carlos Curbelo in 2018, she called the climate crisis “one of the most pressing issues facing our country.” In 2019, she introduced bipartisan legislation to protect coral reefs and helped secure over $200 million in funding for an Everglades restoration project. The League of Conservation Voters, or LCV, gave her a score of 97 percent based on her environmental voting record in 2019.

Gimenez, a former firefighter and current mayor of Miami-Dade County, has also taken steps to prioritize climate action. Although he opposes a tax on carbon, he pledged to reduce the county’s greenhouse gas emissions and protect its cities from sea-level rise.

But unlike other coastal communities, such as New York’s 11th, both candidates in Florida’s District 26 are opposed to the Army Corps of Engineers’ proposal to build a 13-foot high sea wall around Miami. The project would cost roughly $8 billion and would require the federal government to appropriate hundreds of beachfront properties.

“The wall’s not something we’re going to be saying yes to in Miami-Dade County,” Gimenez told the Miami Herald, calling instead for more research on climate mitigation and adaptation. Mucarsel-Powell agreed, saying the wall would create winners and losers in terms of which communities were protected by the structure.

New Jersey District 2 – 67 percent worried

We’ve already seen how climate concern can blur the line between Republicans and Democrats on policy, but this South Jersey district takes that ambiguity to a whole new level. Following the House impeachment of Donald Trump 2019, the district’s representative, moderate Jeff Van Drew, announced he was changing his party affiliation from Democrat to Republican.

“I believe that this is just a better fit for me,” Van Drew said at the time as he pledged his “undying support” for the president. Van Drew’s flip-flop caused a Congressional kerfuffle in the lead-up to the election. His anticipated opponent, Republican lawyer and businessperson David Richter, had to relocate his run for office to District 3. The Democratic Congressional Campaign Committee has added this race to its selective “Red to Blue” program, hoping to regain the district for the Democratic Party. Now Van Drew is running a tight race against Democrat Amy Kennedy (who is married to Patrick, a former House member representing Rhode Island and one of those Kennedys).

But having ties to the Democratic Party aren’t all these two District 2 candidates have in common: Both have advocated for various forms of climate action. Van Drew has a lifetime score of 93 percent from the LCV. Before he discovered his “undying” support for Trump, he rejected the president’s withdrawal from the Paris Agreement. While Van Drew does not support the Green New Deal, he has spoken of the pressing need to act on climate. “The people of South Jersey know that climate change is real and that it impacts their quality of life,” he said while he was still a Democrat. As a Republican, Van Drew has been much less vocal on climate issues, but his congressional campaign website flaunts a 2018 bill he wrote banning offshore drilling in the state.

Kennedy, a former public school teacher with a master’s degree in environmental education, wants to block drilling off the coast of New Jersey and achieve 100 percent clean energy by 2050. Also, her campaign website specifically references environmental justice, saying that “we cannot address climate change if we continue to leave impacted communities behind.”

California District 21 – 65 percent worried

Much of the country considers California to be one big hippie commune, but this Central Valley district — about 200 miles north of Los Angeles — is home to one of the fiercest partisan battles in the country. The two candidates, whose views on climate are anything but aligned, are duking it out over everything from water rights to air pollution.

Incumbent T.J. Cox, a Democrat who in 2018 defeated Republican Rep. David Valadao by less than 1,000 votes, has branded himself as a “clean air champion,” according to the LCV. As the chairman of the House Natural Resources Committee’s Oversight and Investigations panel, he told E&E News the group would “hold the Trump Administration accountable for spreading misinformation about climate science.”

Cox will once again face Valadao, who represented the district from 2012 to 2018. He comes from a long line of dairy farmers, and has spent much of his political career trying to divert more water to farmers in the drought-stricken San Joaquin Valley by reducing the amount used to support endangered fish populations. This focus — along with a tendency to blame Democrats rather than climate change for the region’s water shortages — has contributed to a lifetime LCV score of just 5 percent. According to a 2019 climate adaptation report, Kern County, a portion of which is in the district, is predicted to see higher daily temperatures, more heatwaves, increased wildfires, and a diminished snowpack within this century as a result of climate change.

Pennsylvania District 10 – 63 percent worried

In Central Pennsylvania, climate change isn’t just a dividing line between the two House candidates, it’s a chasm.

Scott Perry, the Republican incumbent, infamously blamed God for polluting the Chesapeake Bay. Perry serves on the House Foreign Affairs Committee, where he proposed an unsuccessful amendment to remove climate reporting from the 2018 defense budget, and holds a lifetime rating of 3 percent from the LCV. While Perry supports electrifying dams to produce hydropower, he is a strong supporter of the region’s oil and gas industry, and argues the free market can solve climate change.

Perry faces Pennsylvania’s Democratic Auditor General Eugene DePasquale, the state’s government financial watchdog. While his current role might not sound like an environmental job, DePasquale has used his position to frame environmental inaction as a government accountability issue. In 2014 his department criticized the state’s Department of Environmental Protection for letting the oil and gas industry off the hook for water contamination and falling short on its taxpayer-funded mission to protect the environment.

In 2019, DePasquale’s department released a report, framing climate inaction as a dollars-and-cents issue. It detailed the billions of dollars needed to fix infrastructure damaged by floods, expand the electrical grid to support more air conditioners, rebuild the Philadelphia airport as a result of sea-level rise, and respond to the public health and infectious disease issues linked to climate change. “Your tax dollars will increasingly be spent to clean up after such disasters if state government does not step up now and limit our contribution to the climate crisis,” DePasquale wrote.

Interestingly, the Democrat doesn’t see climate plans like the Green New Deal as realistic — despite being painted as a supporter of it by his opponent.

Texas District 24 – 62 percent worried

Neither House candidate denies the existence of climate change in this northern Texas district, which includes suburbs north of Dallas and Fort Worth. But the two contenders have extremely different visions for what the region should do about it.

Texas’ District 24 has been controlled by the GOP since Tea Party Republican Rep. Kenny Marchant was first elected in 2004. Marchant has stepped down to allow Beth Van Duyne, the former mayor of Irving, 20 minutes west of Dallas, to run for the seat. But despite Van Duyne’s close ties to the Trump administration — she left the mayorship in 2017 to serve as a regional administrator for the Department of Housing and Urban Development — she has broken from the president in calling climate change “undeniable,” though it’s unclear whether she accepts that it’s caused by humans.

Van Duyne favors developing emissions-free nuclear capacity in order to help Texas achieve greater “energy independence” and “show countries like China and India that there are better ways forward for energy development than more coal plants.” She has also supported efforts between the mayors of Dallas, Arlington, and Fort Worth to create a year-round schedule to conserve Texas’ water. But overall, she is not pro-regulation, calling Environmental Protection Agency rules “crippling” for Texas’ cities. Van Duyne’s challenger is Candace Valenzuela, a former school board member who, if elected, would be the first Black Latina in Congress. Her environmental platform emphasizes equity, and she has promised to make combating climate change and advancing social and climate justice her top priorities. Valenzuela’s campaign has highlighted her struggles with homelessness, and painted its candidate as more in touch with the realities of the district’s lower- and middle-income voters.

Likewise, Valenzuela has drawn on her personal connections when framing the climate crisis. In a YouTube video, she described having to give her two sons breathing treatments as a result of the poor air quality from nearby oil and gas operations. “We need to focus on investing in renewable energy options, such as solar, wind, and geothermal, while massively reducing our dependence on coal, gas, and oil,” she tweeted. “Yes, even in Texas.”