Eight years ago, the field of carbon removal amounted to a handful of academic lab projects and a few fledgling companies working on a novel concept: sucking carbon out of the atmosphere.

That was when Giana Amador, an undergrad at the University of California, Berkeley, founded a nonprofit called Carbon180 with another student, Noah Deich. They hoped to convince policymakers and the climate community that reversing carbon emissions — in addition to reducing them — was essential to limiting the worst impacts of climate change.

A lot has changed since then. Scientists have become more outspoken about the need for carbon removal. Last year, a major U.N. report concluded that achieving international climate goals would be nearly impossible without cleaning up some of what’s already been emitted. Startups hoping to do that now number in the hundreds. Universities have opened research centers to explore the best methods. Private companies and venture capital firms have committed hundreds of millions in the cause, and Washington has followed suit. There’s a new carbon removal research program within the Department of Energy, $3.5 billion in federal funding available to build machines that extract carbon from the air, and a tax credit of up to $180 for every ton of carbon those machines sequester underground.

This explosive growth led Amador to see the need for a different type of advocacy. Last week, she launched the Carbon Removal Alliance, a group of startups and investors that will lobby for policies that support “high quality, permanent carbon removal.”

“I’m really excited that we have more than 20 companies who have come together around those principles to set the bar for what good carbon removal should look like,” Amador, the group’s executive director, told Grist.

The group’s explicit focus on “high quality” or “good” carbon removal underscores a simmering debate within the field about how to best meet the challenge of cleaning up the atmosphere, drawing a stark line between methods that could remove and store carbon for millennia, and those that are more temporary.

There’s generally two reasons scientists say carbon removal will be necessary to tackle climate change. First, it’s a way to balance out emissions that are hard to eliminate, like those from airplanes or agriculture. Second, if the planet warms more than 1.5 degrees Celsius, (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) as many models show is likely, taking carbon out of the atmosphere will be the only way to cool it down. There’s no consensus on exactly how much carbon removal will ultimately be needed, but scientists put the number at between 450 and 1,100 gigatons by the end of the century.

Nearly all of the carbon removed from the atmosphere to date has been accomplished by nature. A recent review of the state of CO2 removal estimates that conventional land management techniques, like reforestation, take up about 2 gigatons of carbon dioxide per year, or roughly 5 percent of global fossil fuel emissions in 2021. Trees, soils, wetlands, and other natural carbon sinks can be enhanced to absorb even more of it, and many companies are focused on doing so. But these are considered short-duration solutions. Wildfires, droughts, diseases, and natural death threaten the carbon stored in trees, while any perturbation to soils and wetlands can also cause a release. Polluting companies often buy carbon offsets derived from these relatively short term solutions. But scientists have criticized that practice, noting that fossil fuel emissions stay in the atmosphere for thousands of years, while trees typically store carbon for hundreds, or less.

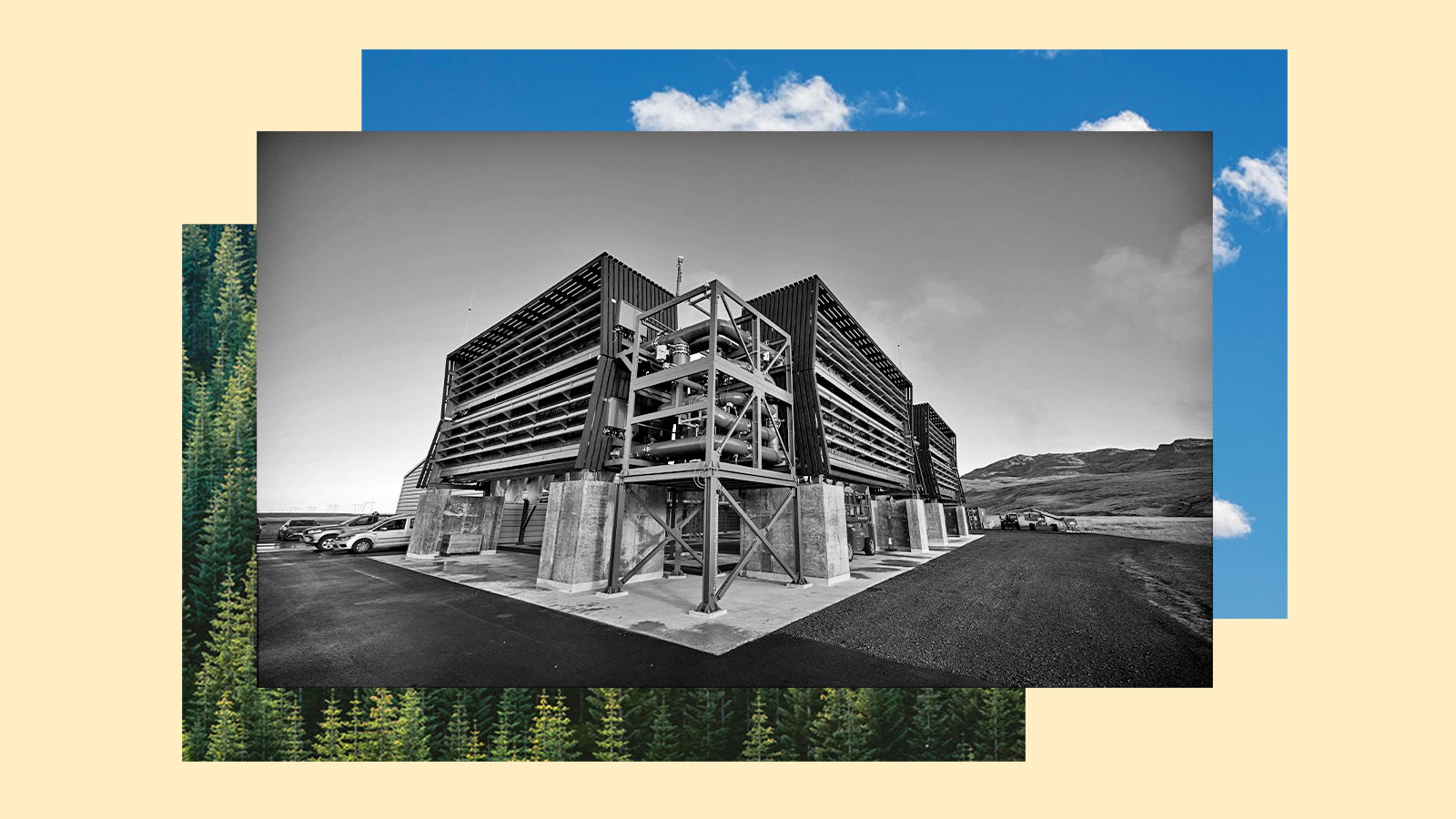

The Carbon Removal Alliance, by contrast, is comprised of companies focused on sucking up carbon and storing it practically forever. Some, like Climeworks, build direct air capture machines that suck up air, separate the carbon, then stash it underground. Others, like Charm Industrial, refine corn stalks into a stable, viscous oil and inject it into the earth’s crust. Other companies grind up rocks and spread them on agricultural fields to accelerate a natural weathering process that absorbs carbon. Still others hope to sink carbon into the depths of the ocean. But these approaches are far more expensive and technologically challenging than planting trees. It’s not yet clear what a successful business model for permanent carbon removal looks like. So far entrepreneurs have relied on venture capital and on selling their services as pricy carbon offsets to a few benevolent companies eager to support the field.

Many members of the Alliance aim to distance themselves from traditional carbon offsets not only by advancing methods with longer time scales, but also by pushing for more rigorous standards for measuring and verifying the amount of carbon they remove. Researchers have found that many forest and soil-based projects are rife with accounting issues and don’t remove as much carbon as they claim to. But while newer, more highly engineered approaches have come a long way since Amador started, they have yet to remove meaningful amounts either.

“We’ve made a lot of progress in the field,” she said. “That being said, we’ve still only captured about 10,000 tons of permanent carbon removal today. And that is a very, very small fraction of the billions of tons that we need to be capturing 30 years from now.” She said the next chapter is about building larger, proof of concept projects, and driving down the cost.

Amador and other members of the Alliance make clear that cutting emissions is much more urgent in the near term. But they argue that permanent carbon removal will not be an option later without immediate, sustained investment. Companies need funding and regulatory support to determine what works; what the risks are, and how to measure the benefits. And while policymakers have started to create programs to support the field, they have focused on a narrow set of solutions. Take the $180 per ton tax credit, for example. Only direct air capture projects can claim it. Peter Reinhardt, the CEO and founder of Charm Industrial, was frustrated that his company’s bio-oil solution didn’t qualify despite his best efforts to lobby lawmakers.

“What actually matters is how much carbon we get out of the atmosphere and put underground,” he said. “And so I made kind of a solo effort to try to push that, and learned very quickly that building a broad coalition is the only effective way to get things done.” That’s why he joined other founding members in creating the Carbon Removal Alliance.

The group wants to discourage policymakers from supporting specific technologies and instead prioritize certain criteria, like the length of carbon storage. It’s an approach that another carbon removal trade association, the Carbon Business Council, disagrees with.

“We see the benefits of an all-of-the-above strategy and not necessarily choosing one or the other,” said Ben Rubin, the organization’s executive director.

The council launched last year and includes more than 80 members representing a wide array of solutions. While there’s some overlap with the Carbon Removal Alliance, the group also has entrepreneurs focused on capturing carbon in soil and trees, and on using the material to make products like jet fuel and diamonds. It also has a handful of members focused on building carbon credit marketplaces to help companies commercialize their services.

Rubin said the benefit of relatively temporary forms of carbon removal is they are “bountiful on the market today,” and very affordable. “If the CO2 is re-released in the future, we still think it has a role in helping to buy society the time we need to decarbonize. As we look at the trends of where renewable energy is heading, electric vehicle adoption is heading, we need more time.”

Amador agrees with that idea, at least in the short term. She didn’t dismiss the possibility that the two groups might work together. “But the reason why we’re focused on long-term is because we know, from a climate perspective, we need to be storing carbon on timescales that match how long carbon actually stays in our atmosphere,” she said.