National Museaum of American HistorySteel moldboard plow developed by John Deere in 1838.

If you have an image in your head when you think “plow,” it’s probably a moldboard plow: a deep cutting edge that swoops up and out into a curved wing, the moldboard. As the plow moves forward, it lifts the earth and flips it, inverting sod into neat lines of corduroy.

The point of plowing is to kill. It wipes out perennial plants and buries seeds deeply enough that they’ll never have a chance to grow. There’s something beautiful about the plow and its action of bringing linear order to the chaos of a weedy field. But there’s nothing natural about the act. Nature only rarely turns the land upside down — only during disasters.

As a result, soil organisms have not evolved to thrive in this kind of tillage. Soil ecosystems, made up of insects and worms, microbes and fungi, are arranged according to depth and chemical needs. For instance, many soil microbes near the surface need oxygen, but oxygen is toxic to others that live deeper down. This ecosystem responds to being turned upside-down the same way a rainforest would: It falls apart. In the process, soil erodes, waterways are polluted, and greenhouse gases are released.

Dwight SiplerModern moldboard plow.

Monsanto and its competitors advertised herbicide-tolerant transgenic plants as a solution to this problem. Instead of plowing, you could use chemicals to deal with the weeds. Genetic engineering would lead to a boom in no-till farming, company representatives said.

Is that what actually happened? There are indeed farmers around the world who have embraced no-till farming because herbicide-tolerant corn made it easier. But judging from the statistics, most low- or no-till farmers in the U.S. are more like Brian Scott.

Brian Scott.

Scott, the Indiana farmer who I first wrote about here, never even learned how to use a moldboard plow. He practices conservation tillage, which is a step down from no-till: He still uses a cultivator, but doesn’t completely turn the ground. And he’s been doing this for a long time. When I asked if he had a mentor for conservation tillage, he said, “It would have to be dad and grandpa.”

“We still own a moldboard plow and I hope it never pokes its head out of the shed again,” he wrote in an email.

In other words, for Scott’s family, conservation tillage came long before genetic engineering. Still, having the option to spray herbicide after the transgenic crops emerge (without killing them) can make farmers better stewards, Scott said:

The ability to control weeds more effectively with safer herbicides post-emergence [after the crop comes up] is conducive to reducing tillage. In the past we might have run a rotary hoe two or three times in the spring before planting soybeans to get a clean seedbed. With corn, ground was worked both in the fall and spring ahead of corn planting and then we would take a row crop cultivator out during the growing season to manage weeds post-emergence.

With herbicide-tolerant crops, Scott works the ground far less — and sometimes not at all. That means there’s more plant residue on the ground, which means the ground is more productive, it holds the water better, and it’s less likely to wash or blow away.

Scott’s tractor doesn’t bear moldboard plows, but it does take kids.

Farmers burn a lot less diesel when they aren’t plowing, and the residue provides habitat for wildlife. Finally, instead of dirt forming into big clots of compacted soil, farmers who minimize tillage find that their dirt is looser, aerated by billion of tiny passageways: When the tractors stop plowing, the earthworms and microbes start plowing. The tradeoff, of course, is that most of these farmers also use herbicide. But then, conventional farmers tend to use herbicide anyway.

“Does conservation tillage automatically increase your herbicide inputs? Overwhelmingly, the answer is no,” said Jeff Mitchell, a U.C. Davis Cooperative Extension specialist who works on conservation agriculture.

It’s a somewhat separate question to ask if herbicide tolerance has led farmers to adopt conservation tillage.

“I’ve heard farmers here in California say that Roundup Resistant crops effectively allowed some people to start doing conservation tillage,” Mitchell said. “But you have to remember, the vast majority of farmers in the U.S. using Roundup Ready seed don’t do conservation tillage.”

“I’ve looked really closely at the whole no-till thing, and that’s just a fallacy,” said Bill Freese of the Center for Food Safety. Conservation tillage hasn’t been helped much by genetic engineering, and it’s actually on the decline, he said.

Pro-GE people tend to say just the opposite: According to them, conservation tillage is going up, up, up. The reason this discrepancy exists is that we haven’t had any good data for nearly a decade. That’s because, thanks to budget cutbacks, the USDA stopped paying to collect this information. So everything since 2004 is based on estimates, projections, and anecdotes. Craig Cox of the Environmental Working Group says that everyone he’s talked to says there’s been a decline in conservation tillage as farmers rush to cash in on high corn prices.

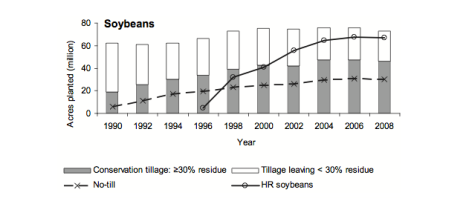

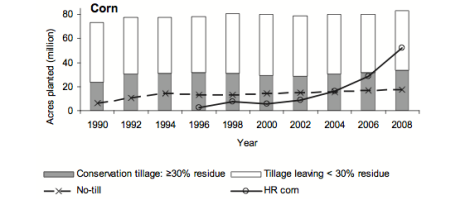

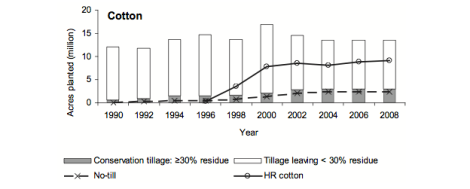

The most convincing analysis I could find came from a National Research Council report. A review of the science suggests that herbicide tolerance does help some farmers move to conservation tillage, but it doesn’t necessarily drive them into the practice. When I study the graphs in that NRC report, I see things moving in the right direction, but herbicide tolerance does not look like some golden key that unlocked conservation tillage for American farmers. Click to embiggen:

The story is different in Argentina and Brazil, where an important rise in conservation tillage really is tied to herbicide tolerance, said Charles Benbrook, a research professor at Washington State University, when I spoke to him for my last piece on this issue. In those countries farmers have converted more recently to intensive agriculture, and, in doing so, have adopted the whole package: herbicides, GM crops, insecticides, and conservation tillage practices. As a result, they are producing a lot of calories while binding up a lot of carbon in the soil, but they may also be producing some real problems. Farmers have increased the amount of agrochemicals they use nine fold since 1990 in Argentina, and currently use twice as much per acre as U.S. farmers, according to the Associated Press.

When I asked soil scientist Garrison Sposito about GM crops and conservation tillage, he began walking me through one scenario after another. Do you really need herbicide, I asked? Do you really need GMOs? The answer to both questions, it seems, is no, with a caveat. Without these things, yields go down — you might need more land to produce the same amount of food. It all depends on what you want to get out of the situation.

“You never solve problems by making changes,” Sposito said. “What you do by making changes is exchange one set of problems for another set of problems.”

Have GMOs triggered conservation-minded agriculture? In the U.S., just a little bit.

More in this series:

- The genetically modified food debate: Where do we begin?

- The GM safety dance: What’s rule and what’s real

- Genetic engineering vs. natural breeding: What’s the difference?

- Genetically engineered food: Allergic to regulations?

- Genetically modified seed research: What’s locked and what isn’t

- Is extremism in defense of GM food a vice?

- Food for bots: Distinguishing the novel from the knee-jerk in the GMO debate

- Golden Rice: Fool’s gold or golden opportunity?

- Golden apple or forbidden fruit? Following the money on GMOs

- Are GMOs worth their weight in gold? To farmers, not exactly Lesser of two weevils: GMOs vs. insecticides

- Roundup-ready, aim, spray: How GM crops lead to herbicide addiction