Walk into the grocery store and check the back of a container of food. Chances are, you’ll see a small box with instructions on how to dispose of the packaging when you’re finished with it: “empty & replace lid,” for example, or “recycle if clean and dry.”

These labels are made by How2Recycle, a program operated by the nonprofit GreenBlue, which sells them to more than 700 big food and consumer goods companies to put on their products. The idea behind creating them was to mitigate confusion among consumers about what to do with all the boxes, jars, jugs, and bottles that their purchases are packed in.

In recent years, however, companies have come under scrutiny for being too liberal with their use of the iconic “chasing arrows” recycling symbol: It makes plastic bags and other products seem more recyclable than they really are. Regulators have taken notice. At the national level, the Federal Trade Commission is preparing an update to its “Green Guides” for the use of sustainability labels, including the recycling symbol. And in California, state law is expected to restrict the chasing arrows for most packaging made of plastic, unless there’s evidence that the plastic is widely collected and turned into new products within the state. How2Recycle’s program, created to help clear up this mess, is coming under fire now, too

Earlier this month, GreenBlue announced it was revamping its more-than-a-decade-old How2Recycle labels. During a presentation at SPC Advance, a conference organized by one of GreenBlue’s subsidiaries, Paul Nowak, GreenBlue’s executive director, said the labels need to “evolve with the world around us,” taking into account factors like “policy” and “recycling rates.”

Based on a sample image of the new labels, however, it’s not clear whether GreenBlue’s updates will address concerns that they’re tools for so-called greenwashing, or that they comply with state law. Because there’s no evidence that some of the products set to feature the new designs are actually recycled most of the time, the labels might violate California’s rules against deceptive advertising and put GreenBlue at risk of lawsuits from state regulators and consumer advocacy organizations.

The proposed labels are “an obvious and transparent attempt by industry to circumvent California law,” said Howie Hirsch, a retired lawyer in California who has worked on several recycling-related deceptive advertising lawsuits.

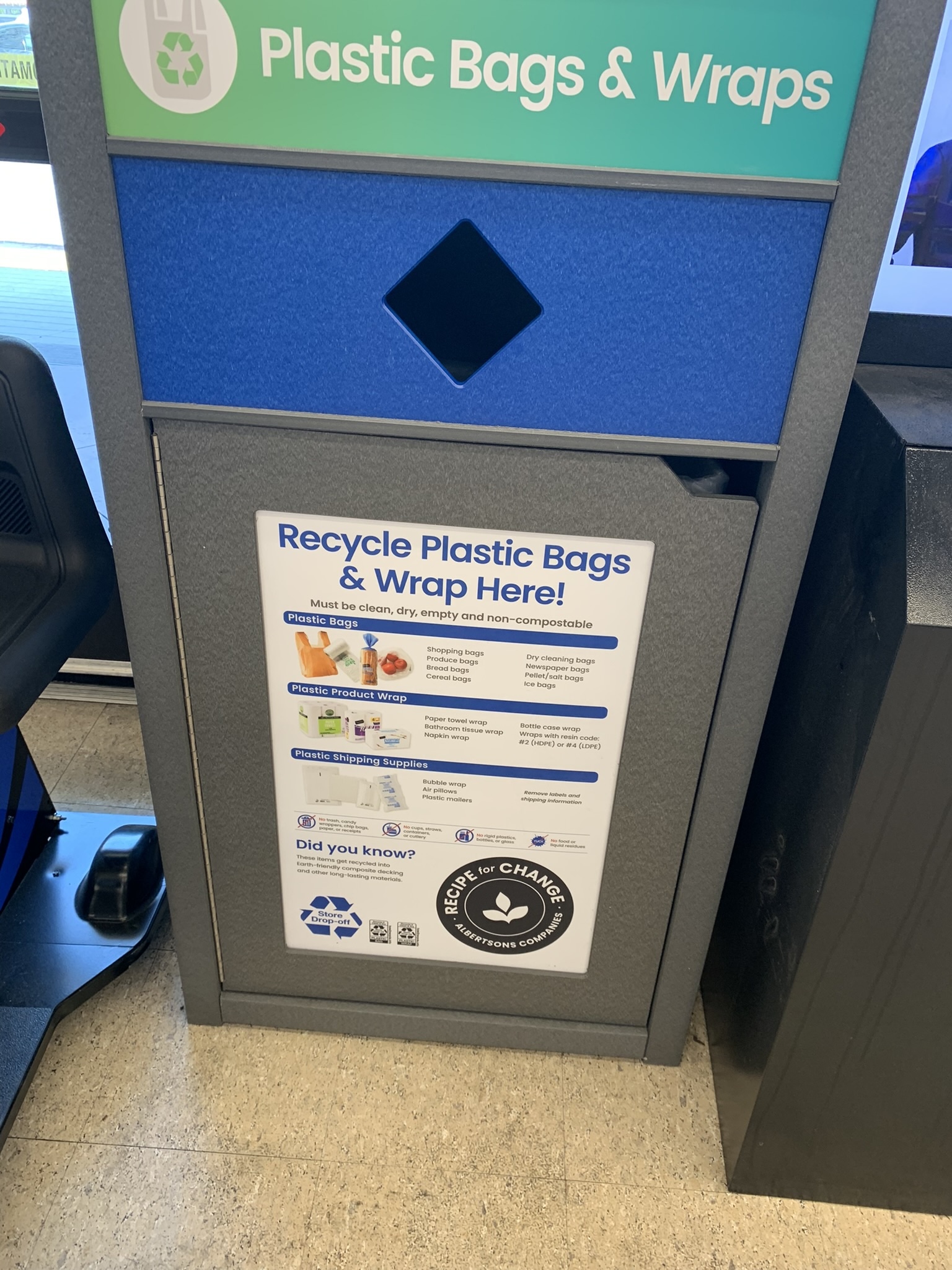

Hirsch specifically objects to GreenBlue’s label for “store drop-off,” which instructs customers to deposit plastic bags in grocery store take-back bins so they can be collected for recycling. Currently, this label features the words “store drop-off” inside a triangular chasing arrows symbol — giving the inaccurate impression that this plastic is likely to be recycled. A revised version of that label, shared in Nowak’s presentation, simply changes the arrows’ path: Instead of chasing each other around a triangle, they now chase each other around a circle.

A store drop-off receptacle for plastic bags and wraps (left), and a packaging label with an older version of How2Recycle’s “store drop-off” label. Courtesy of Jan Dell

According to Hirsch, that small change isn’t enough to comply with California law. First, one section of the California Business and Professions Code says that the chasing arrows triangle is functionally equivalent to — and subject to the same truth-in-labeling restrictions as — the circular version proposed by GreenBlue. The law applies to any variant of the symbol that is “likely to be interpreted by a consumer as an implication of recyclability” — including “one or more arrows arranged in a circular pattern or around a globe.”

Another part of California’s law referring to the FTC’s Green Guides requires the corroboration of recyclability claims: Companies that label their products with the chasing arrows have to provide evidence that they are, in fact, widely collected for recycling and turned into new products within California. Plastic bag manufacturers have not provided such evidence, and they are under investigation from the California attorney general’s office after failing to do so.

The circular chasing arrows “seems to be just the kind of thing that we were hoping to push back against,” said California State Senator Ben Allen, a Democrat who sponsored a landmark bill to reign in the misleading use of the recycling symbol that became law in 2022. A separate law passed last month will phase out plastic grocery bags offered to California shoppers at checkout. But many other types of plastic bags and thin-film plastic will still be allowed.

Jan Dell, an independent chemical engineer and founder of the nonprofit The Last Beach Cleanup, would like to see How2Recycle’s store drop-off labels disappear altogether. Store drop-off is “a hoax,” she told Grist via email. “All credible data, independent experts, and many tracker studies prove that it is impossible to collect, sort, and recycle post-household consumer flexible plastic waste” on a meaningful scale.

According to an analysis Dell conducted in 2020, California only has the capacity to sort and recycle about 1 percent of its waste generated from plastic bags and film. Nationwide tracker studies from Bloomberg and ABC News — using Apple AirTags or similar devices — have shown that plastic bags deposited in store drop-off receptacles are more likely to end up in a landfill or incinerator than at a recycling facility.

Allen’s truth-in-labeling law will soon add even more specific requirements for the chasing arrows and other symbols like it. Starting 18 months after the state’s recycling agency publishes a report on the recyclability of various materials, companies will have to show that products labeled as recyclable through a non-curbside program — like at a grocery store — are collected at a rate of 60 percent or higher, and then sorted and recycled within the state. That threshold will bump up to 75 percent in 2030.

Recent analyses suggest it’s unlikely that any types of plastic bags or film will meet those high standards. In 2020, the Flexible Packaging Association said the U.S. recycling rate for post-consumer film and flexible plastic packaging was just 2 percent. The Ellen MacArthur Foundation, a nonprofit that advocates for a circular economy, estimates that “near 0 percent” of flexible plastics sold to consumers around the world is recycled; what little recycling that does happen involves turning polyethylene film into “applications of lower material quality” like plastic decking and trash bags.

“As soon as flexible packaging waste is generated it is incredibly hard to deal with,” the foundation’s report says. As a first order of business, it recommends eliminating “unnecessary” plastic products.

In response to Grist’s request for comment, a spokesperson for GreenBlue said the organization is reviewing its proposal for new labels with government agencies, including the FTC and state attorneys general, “to ensure that pairing the label’s symbol with additional clarifying information would constitute a thoroughly substantiated claim.”

“If regulators deem the label not in compliance with California’s SB 343,” the spokesperson added, “How2Recycle will pursue a different label design.”

A spokesperson for the California Attorney General’s office declined to comment on the How2Recycle labels and would not confirm whether the office had spoken with GreenBlue. The FTC did not respond to Grist’s request for comment.

Allen, the California state senator, said the plastics industry’s time would be better spent redesigning products and eliminating unnecessary packaging to comply with recent laws, instead of fiddling with labels. In addition to the truth-in-labeling regulation, as of 2022, California has an extended producer responsibility law requiring companies to meet elevated recycling targets for certain types of products.

“If they’ve got a real plan to fundamentally revamp recycling in this space, then I’m interested in hearing about it,” Allen said. “But claiming recyclability or encouraging people to do something that they know they’re never going to do in a meaningful way” — like dropping off bags at a store — “it’s greenwashing and it’s a joke, and I just don’t want us to allow for it.